Moai facts for kids

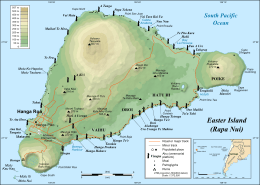

Moai are stone statues on Easter Island. Each moai is made out of one large stone but some have an extra stone on top of the head. Most were made from the volcanic rock in the Rano Raraku area of the island. Moai are sometimes called "heads" but they do have shoulders, arms, and a body but these are usually too small for the head, also some of the best known ones had been partly buried over the years and only the heads were showing. Most moai are between 2.5 and 10 metres high and, usually, weigh 14 tonnes. There are about 1000 moai placed mainly around the coast of the island plus nearly 400 more which were left not yet finished at Rano Raraku.

When, why, and how they were made is still a mystery today. It is believed that they were made almost 1000 years ago by Polynesians, who lived there at the time and were made to honour their ancestors (older family members long dead) and bring good luck. Making the statues would have needed a lot of time and effort. To move them, they may have used wooden sledges or rollers or even "walked" them by rocking the moai along. The youngest moai found was built around 1350. It is believed that, around that time, there began a time of cold weather, little food, and war between the peoples. By the 19th century, all the moai had been pushed over. Today, some have been restored.

Contents

Description

The moai are monolithic statues, their minimalist style related to forms found throughout Polynesia. Moai are carved in relatively flat planes, the faces bearing proud but enigmatic expressions. The human figures would be outlined in the rock wall first, then chipped away until only the image was left. The over-large heads (a three-to-five ratio between the head and the trunk, a sculptural trait that demonstrates the Polynesian belief in the sanctity of the chiefly head) have heavy brows and elongated noses with a distinctive fish-hook-shaped curl of the nostrils. The lips protrude in a thin pout. Like the nose, the ears are elongated and oblong in form. The jaw lines stand out against the truncated neck. The torsos are heavy, and, sometimes, the clavicles are subtly outlined in stone. The arms are carved in bas relief and rest against the body in various positions, hands and long slender fingers resting along the crests of the hips, meeting at the hami (loincloth), with the thumbs sometimes pointing towards the navel. Generally, the anatomical features of the backs are not detailed, but sometimes bear a ring and girdle motif on the buttocks and lower back. Except for one kneeling moai, the statues do not have clearly visible legs.

Though moai are whole-body statues, they are erroneously referred to as "Easter Island heads" in some popular literature. This is partly because of the disproportionate size of most moai heads, and partly because many of the iconic images for the island showing upright moai are the statues on the slopes of Rano Raraku, many of which are buried to their shoulders. Some of the "heads" at Rano Raraku have been excavated and their bodies seen, and observed to have markings that had been protected from erosion by their burial.

The average height of the moai is about 4 m (13 ft), with the average width at the base around 1.6 m (5.2 ft). These massive creations usually weigh in at around 12.5 tonnes (13.8 tons) each.

All but 53 of the more than 900 moai known to date were carved from tuff (a compressed volcanic ash) from Rano Raraku, where 394 moai in varying states of completion are still visible today. There are also 13 moai carved from basalt, 22 from trachyte and 17 from fragile red scoria. At the end of carving, the builders would rub the statue with pumice.

Characteristics

Easter Island statues are known for their large, broad noses and strong chins, along with rectangle-shaped ears and deep eye slits. Their bodies are normally squatting, with their arms resting in different positions and are without legs. The majority of the ahu are found along the coast and face inland towards the community. There are some inland ahu such as Ahu Akivi. These moai face the community but given the small size of the island, also appear to face the coast.

Eyes

In 1979, Sergio Rapu Haoa and a team of archaeologists discovered that the hemispherical or deep elliptical eye sockets were designed to hold coral eyes with either black obsidian or red scoria pupils. The discovery was made by collecting and reassembling broken fragments of white coral that were found at the various sites. Subsequently, previously uncategorized finds in the Easter Island museum were re-examined and recategorized as eye fragments. It is thought that the moai with carved eye sockets were probably allocated to the ahu and ceremonial sites, suggesting that a selective Rapa Nui hierarchy was attributed to the moai design until its demise with the advent of the Birdman religion, Tangata Manu.

Symbolism

Many archaeologists suggest that "[the] statues were thus symbols of authority and power, both religious and political. But they were not only symbols. To the people who erected and used them, they were actual repositories of sacred spirit. Carved stone and wooden objects in ancient Polynesian religions, when properly fashioned and ritually prepared, were believed to be charged by a magical spiritual essence called mana." Archaeologists believe that the statues were a representation of the ancient Polynesians' ancestors. The moai statues face away from the ocean and towards the villages as if to watch over the people. The exception is the seven Ahu Akivi which face out to sea to help travelers find the island. There is a legend that says there were seven men who waited for their king to arrive.

Pukao topknots and headdresses

The more recent moai had pukao on their heads, which represent the topknot of the chieftains. According to local tradition, the mana was preserved in the hair. The pukao were carved out of red scoria, a very light rock from a quarry at Puna Pau. Red itself is considered a sacred color in Polynesia. The added pukao suggest a further status to the moai.

Markings (post stone working)

When first carved, the surface of the moai was polished smooth by rubbing with pumice. Unfortunately, the easily worked tuff from which most moai were carved is also easily eroded, and, today, the best place to see the surface detail is on the few moai carved from basalt or in photographs and other archaeological records of moai surfaces protected by burials.

Those moai that are less eroded typically have designs carved on their backs and posteriors. The Routledge expedition of 1914 established a cultural link between these designs and the island's traditional tattooing, which had been repressed by missionaries a half-century earlier. Until modern DNA analysis of the islanders and their ancestors, this was key scientific evidence that the moai had been carved by the Rapa Nui and not by a separate group from South America.

At least some of the moai were painted; Hoa Hakananai'a was decorated with maroon and white paint until 1868, when it was removed from the island. It is now housed in the British Museum, London.

History

The statues were carved by the Polynesian colonizers of the island, mostly between circa 1250 A.D. and 1500 A.D. In addition to representing deceased ancestors, the moai, once they were erected on ahu, may also have been regarded as the embodiment of powerful living or former chiefs and important lineage status symbols. Each moai presented a status: "The larger the statue placed upon an ahu, the more mana the chief who commissioned it had." The competition for grandest statue was ever prevalent in the culture of the Easter Islanders. The proof stems from the varying sizes of moai.

Completed statues were moved to ahu mostly on the coast, then erected, sometimes with red stone cylinders (pukao) on their heads. Moai must have been extremely expensive to craft and transport; not only would the actual carving of each statue require effort and resources, but the finished product was then hauled to its final location and erected.

The quarries in Rano Raraku appear to have been abandoned abruptly, with a litter of stone tools and many completed moai outside the quarry awaiting transport and almost as many incomplete statues still in situ as were installed on ahu. In the nineteenth century, this led to conjecture that the island was the remnant of a sunken continent and that most completed moai were under the sea. That idea has long been debunked, and now it is understood that:

- Some statues were rock carvings and never intended to be completed.

- Some were incomplete because, when inclusions were encountered, the carvers would abandon a partial statue and start a new one (tuff is a soft rock with occasional lumps of much harder rock included in it).

- Some completed statues at Rano Raraku were placed there permanently and not parked temporarily awaiting removal.

- Some were indeed incomplete when the statue-building era came to an end.

Craftsmen

It is not known exactly which group in the communities were responsible for carving statues. Oral traditions suggest that the moai were either carved by a distinguished class of professional carvers who were comparable in status to high-ranking members of other Polynesian craft guilds, or, alternatively, by members of each clan. The oral histories show that the Rano Raraku quarry was subdivided into different territories for each clan.

Images for kids

-

Moai facing inland at Ahu Tongariki, restored by Chilean archaeologist Claudio Cristino in the 1990s

-

.

Petroglyphs on the back of an excavated moai.

-

Ahu Akivi, the furthest inland of all the ahu

-

Original moai at the Louvre Museum, in Paris

-

Early European drawing of moai, in the lower half of a 1770 Spanish map of Easter Island; the original manuscript maps of the Spanish expedition are in Naval Museum of Madrid and in The Jack Daulton Collection, US.

-

Tukuturi at Rano Raraku is the only kneeling moai and one of the few made of red scoria.

-

Moai on the Easter Island, a painting by William Hodges, 1775–76

See also

In Spanish: Moái para niños

In Spanish: Moái para niños