Milan Kundera facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Milan Kundera

|

|

|---|---|

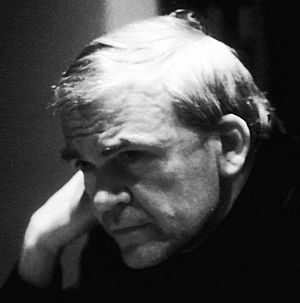

Kundera in 1980

|

|

| Born | 1 April 1929 Brno, Czechoslovakia (present-day Czech Republic) |

| Died | 11 July 2023 (aged 94) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | Charles University Academy of Performing Arts in Prague |

| Notable works | The Joke (in original Žert) (1967) The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (in original Kniha smíchu a zapomnění (1979) The Unbearable Lightness of Being (in original Nesnesitelná lehkost bytí (1984) |

| Notable awards | Jerusalem Prize 1985 The Austrian State Prize for European Literature 1987 Vilenica International Literary Festival 1992 Herder Prize 2000 Czech State Literature Prize 2007 |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Milan Kundera ( 1 April 1929 – 11 July 2023) was a Czech-born French novelist. Kundera went into exile in France in 1975, acquiring citizenship in 1981. His Czechoslovak citizenship was revoked in 1979 but he was granted Czech citizenship in 2019. He saw himself as a French writer and insisted his work should be studied as French literature and classified as such in book stores.

Kundera's best-known work is The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Prior to the Velvet Revolution of 1989, the communist regime in Czechoslovakia banned his books. He led a low-profile life and rarely spoke to the media. He was thought to be a contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature, and was also a nominee for other awards.

Kundera was awarded the 1985 Jerusalem Prize, in 1987 the Austrian State Prize for European Literature, and the 2000 Herder Prize. In 2021, he received the Golden Order of Merit from the president of Slovenia.

Contents

Biography

Kundera was born in 1929 at Purkyňova 6 (6 Purkyně Street) in Královo Pole, a quarter of Brno, Czechoslovakia, to a middle-class family. His father, Ludvík Kundera (1891–1971), was an important Czech musicologist and pianist who served as the head of the Janáček Music Academy in Brno from 1948 to 1961. His mother was Milada Kunderová (born Janošíková).

Milan learned to play the piano from his father and later studied musicology and musical composition. Musicological influences, references and notation can be found throughout his work. Kundera was a cousin of Czech writer and translator Ludvík Kundera. He belonged to the generation of young Czechs who had had little or no experience of the pre-war democratic Czechoslovak Republic. Their ideology was greatly influenced by the experiences of World War II and the German occupation.

Still in his teens, he joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in 1947. At the time, he was a committed Communist and enthusiastically welcomed the "Prague coup" of 1948, which saw the Communist Party take power in Czechoslovakia with the support of the Soviet Union. "Around 1948, I too (...) exalted the revolution," Kundera admitted in 1981. "Communism captivated me as much as Stravinsky, Picasso and Surrealism", he added in 1984.

His first printed text, in 1947, was a poem dedicated "To the memory of Pavel Haas", his music teacher, murdered in the Nazi death camps. He completed his secondary school studies in Brno at Gymnázium třída Kapitána Jaroše in 1948. He studied literature and aesthetics at the Faculty of Arts at Charles University in Prague. After two terms, he transferred to the Film Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague where he first attended lectures in film direction and script writing.

In 1950, his studies were interrupted when he and writer Jan Trefulka were expelled from the Communist Party for "anti-party activities". Trefulka described the incident in his novella Pršelo jim štěstí (Happiness Rained on Them, 1962). Kundera also used the expulsion as an inspiration for the main theme of his novel Žert (The Joke, 1967). After Kundera graduated in 1952, the Film Faculty appointed him a lecturer in world literature. In 1956 Kundera was readmitted to the Party but was expelled for the second time in 1970.

Along with other reformist communist writers such as Pavel Kohout, he was peripherally involved in the 1968 Prague Spring. This brief period of reformist activities was crushed by the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968. Kundera remained committed to reforming Czechoslovak communism, and argued vehemently in print with fellow Czech writer Václav Havel, saying, essentially, that everyone should remain calm and that "nobody is being locked up for his opinions yet," and "the significance of the Prague Autumn may ultimately be greater than that of the Prague Spring." Finally, however, Kundera relinquished his reformist dreams and moved to France in 1975. He taught for a few years in the University of Rennes. He was stripped of Czechoslovak citizenship in 1979; he was a French citizen from 1981.

Kundera maintained contact with Czech and Slovak friends in his homeland, but rarely returned and always did so without fanfare.

Kundera died after a prolonged illness, in Paris on 11 July 2023, at the age of 94.

Works

Although his early poetic works are staunchly pro-communist, his novels escape ideological classification. Kundera repeatedly insisted that he was a novelist rather than a politically motivated writer. Political commentary all but disappeared from his novels after the publication of The Unbearable Lightness of Being except in relation to broader philosophical themes. Kundera's style of fiction, interlaced with philosophical digression, was greatly inspired by the novels of Robert Musil and the philosophy of Nietzsche, and was also interpreted philosophically by authors such as Alain de Botton and Adam Thirlwell.

Kundera himself claimed inspiration from Renaissance authors such as Giovanni Boccaccio, Rabelais and, perhaps most importantly, Miguel de Cervantes, to whose legacy he considered himself most committed. Other influences include Laurence Sterne, Henry Fielding, Denis Diderot, Robert Musil, Witold Gombrowicz, Hermann Broch, Franz Kafka, and Martin Heidegger. Originally he wrote in Czech, but from 1993 on he wrote his novels in French. Between 1985 and 1987, he undertook the revision of the French translations of his earlier works himself. His books have also been translated into many other languages.

The Joke

In his first novel, The Joke (1967), he satirized the totalitarianism of the Communist era. His criticism of the Soviet invasion in 1968 led to his blacklisting in Czechoslovakia and the banning of his books.

Life Is Elsewhere

Kundera's second novel was first published in French as La vie est ailleurs in 1973 and in Czech as Život je jinde in 1979. Set in Czechoslovakia before, during, and after the Second World War, Life Is Elsewhere is a satirical portrait of the fictional poet Jaromil, a young and very naïve idealist who becomes involved in political scandals.

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

In 1975, Kundera moved to France where The Book of Laughter and Forgetting was published in 1979. An unusual mixture of novel, short story collection, and authorial musings which came to characterize his works in exile, the book dealt with how Czechs opposed the communist regime in various ways. Critics noted that the Czechoslovakia Kundera portrays "is, thanks to the latest political redefinitions, no longer precisely there," which is the "kind of disappearance and reappearance" Kundera ironically explores in the book. A Czech version, Kniha smíchu a zapomnění, was published in April 1981 by 68 Publishers, Toronto.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Kundera's most famous work, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, was published in 1984. The book chronicles the fragile nature of an individual's fate, theorizing that a single lifetime is insignificant in the scope of Nietzsche's concept of eternal return. In an infinite universe, everything is guaranteed to recur infinitely. In 1988, American director Philip Kaufman released a film adaptation.

Immortality

In 1990, Immortality was published. The novel, his last in Czech, was more cosmopolitan than its predecessors, more explicitly philosophical and less political, as were his later writings.

Identity

In 1998, Identity was published. The novel different stylistically from his past novels, but contained the philosophical questions that can be expected from his writing.

Ignorance

In 2000, Ignorance was published. The novel is centered around themes of immigration and culture shock. Linda Asher translated the original French version of the novel to English in 2002.

The Festival of Insignificance

The 2014 novel focuses on the musings of four male friends living in Paris who discuss their relationships with women and the existential predicament confronting individuals in the world, among other things. The novel received generally negative reviews. Michiko Kakutani of the New York Times describes the book as being a "knowing, pre-emptive joke about its own superficiality". A review in the Economist stated that the book was "sadly let down by a tone of breezy satire that can feel forced."

Writing style and philosophy

Kundera often explicitly identifies his characters as figments of his imagination, using a first-person narrator who comments on the characters in otherwise third-person narratives. Kundera is more concerned with the words that shape or mold his characters than with their physical appearance. In his non-fiction work, The Art of the Novel, he says that the reader's imagination automatically completes the writer's vision so that, as a writer, he is free to focus on the essential aspects of his characters, not on their physical characteristics, which are not critical to understanding them. Indeed, for Kundera the essential may not even include the interior psychological world of his characters. Still, at times, a specific feature or trait may become the character's idiosyncratic focus, such as Zdena's ugly nose in "Lost Letters" from The Book of Laughter and Forgetting.

François Ricard suggested that Kundera conceives his fiction with regard to the overall body of his work, rather than limiting his ideas to the scope of just one novel at a time, his themes and meta-themes traversing his entire œuvre. Each new book manifests the latest stage of his personal philosophy. Some of these meta-themes include exile, identity, life beyond the border (beyond love, beyond art, beyond seriousness), history as continual return, and the pleasure of a less "important" life (François Ricard, 2003).

Many of Kundera's characters seem to develop as expositions of one of these themes at the expense of their full humanity. Specifics in regard to the characters tend to be rather vague. Often, more than one main character is used in a novel; Kundera may even completely discontinue a character, resuming the plot with somebody new. As he told Philip Roth in an interview in The Village Voice: "Intimate life [is] understood as one's personal secret, as something valuable, inviolable, the basis of one's originality".

Kundera's early novels explore the dual tragic and comic aspects of totalitarianism. He did not view his works, however, as political commentary. "The condemnation of totalitarianism doesn't deserve a novel", he said. According to the Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes, "What he finds interesting is the similarity between totalitarianism and the immemorial and fascinating dream of a harmonious society where private life and public life form but one unity and all are united around one will and one faith". In exploring the dark humor of this topic, Kundera seems deeply influenced by Franz Kafka.

Kundera also ventured often into musical matters, analyzing Czech folk music for example; or quoting from Leoš Janáček and Bartók; or placing musical excerpts into the text, as in The Joke; or discussing Schoenberg and atonality.

Awards and honors

In 1985, Kundera received the Jerusalem Prize. His acceptance address appears among the essays collected in The Art of the Novel. He won The Austrian State Prize for European Literature in 1987. In 2000, he was awarded the international Herder Prize. In 2007, he was awarded the Czech State Literature Prize. In 2009, he was awarded the Prix mondial Cino Del Duca. In 2010, he was made an honorary citizen of his hometown, Brno.

In 2011, he received the Ovid Prize. The asteroid 7390 Kundera, discovered at the Kleť Observatory in 1983, is named in his honor. In 2020, he was awarded the Franz Kafka Prize, a Czech literary award.

See also

In Spanish: Milan Kundera para niños

In Spanish: Milan Kundera para niños