Mike Davis (scholar) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

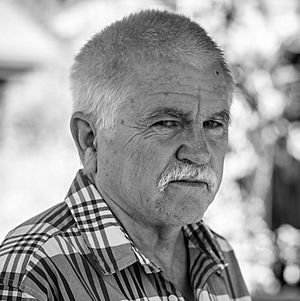

Mike Davis

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Michael Ryan Davis

March 10, 1946 Fontana, California, U.S.

|

| Died | October 25, 2022 (aged 76) San Diego, California, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | University of California, Los Angeles |

| School |

|

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Influences

|

|

Michael Ryan Davis (March 10, 1946 – October 25, 2022) was an American writer, political activist, urban theorist, and historian based in Southern California. He is best known for his investigations of power and social class in works such as City of Quartz and Late Victorian Holocausts. His last non-fiction book is Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties, co-authored by Jon Wiener.

Contents

Biography

Early life and political formation: 1946–1962

Michael Ryan Davis was born in Fontana, California, on March 10, 1946, to Dwight and Mary (Ryan) Davis. Dwight was from Venedocia, Ohio, and was of Welsh and Protestant background. He was a trade-union Democrat and an "anti-racist," which Davis attributed to his ancestors, Welsh abolitionists and Union soldiers who had settled in the Black Swamp of Ohio. Mary was an Irish Catholic from Columbus, Ohio, and the daughter of Jack Ryan, a veteran of the Spanish–American War. Both parents hitchhiked to California during the Great Depression.

Davis was raised in a tract home in the town of Bostonia in San Diego County. His father Dwight worked in the wholesale meat industry for Superior Meat Company in downtown San Diego and was a member of the meat cutter's union, and his uncle ran a wholesale meat company. The nearly all-white neighborhood of Davis's childhood was populated by refugees of the Great Depression, mostly Southern Baptist families from Oklahoma and Texas, and had a country-western ballroom and rodeo. Davis identified with his community as a "redneck" and a "Westerner" in opposition to the "surfer" beach culture held by the wealthier, Methodist neighborhoods south of El Cajon's Main Street. Racism and anti-communism were endemic in the town, but Democrats held the dominant political role in the community due to the influence of the Machinists Union.

Davis described the family home as absent of books save for the Vulgate Bible, but his parents were avid readers of newspapers and the Reader's Digest. As a young man, Davis held conservative and patriotic views, but was not preoccupied with politics, being mostly interested in drag racing, Kerouac, and bullfighting, and followed his father as a meat cutter. Davis drank and stole cars with his friends, which culminated in a near-fatal car accident when he drove his Ford into a brick wall during a drag race, leaving him with a permanent 12 in (30 cm) scar on his left thigh.

In high school, Davis was exposed to John Hershey's Hiroshima, a reading which, in addition to his father's intense dedication to the Meat Cutter's Union and the "Irish class consciousness" of his mother, started his political formation. At 16, his father suffered a catastrophic heart attack which undermined the family's financial security. Davis had to leave school to provide for the family by working as a delivery truck driver for his uncle's wholesale meat company, delivering to restaurants throughout San Diego County. During this period, he met Lee Gregovich, an older communist and Wobbly whose family emigrated from the Dalmatian coast to work in the copper mines of the American southwest. Gregovich was blacklisted from many employers by the HUAC, but had found a job at the Chicken Shack, an establishment in Julian that Davis delivered to. Gregovich urged the young Davis to "read Marx!"

Davis graduated from high school as one of three valedictorians, earning a full scholarship to Reed College.

Young activist: 1962–1968

At Reed College, Davis was overwhelmed, alienated by the hippy culture and struggling academically. He joined the Portland, Oregon chapter of CORE, which included the labor historian Jeremy Brecher, who at the time was one of few members of the nascent Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in the Pacific Northwest. Living in the dorm of a girlfriend for five weeks, Davis was expelled from Reed for intervisitation. Davis was eligible for the draft after his expulsion and passed the physical, but he was rejected after he insisted to the personnel at the induction center he belonged to several subversive organizations. After reading the Port Huron Statement, and at the recommendation of Brecher, Davis boarded a Greyhound bus to New York City to join the national office of SDS, arriving in November of 1963. Between 1964 and 1965, Davis worked in the national office of SDS, which was becoming overwhelmed by the growing number of chapters. The national council meetings gave the office the responsibility to organize two major demonstrations, an Anti-Apartheid sit-in and the first march on Washington in protest of the Vietnam War.

Davis was one of the chief coordinators behind the Anti-Apartheid sit-in at Chase Manhattan Bank. In the aftermath of the Sharpeville massacre, Chase Manhattan had led a consortium of international banks that bailed out the Apartheid government of South Africa. The chief ally and tactical organizer to the sit-in was the New York chapter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), headed by Betita Martinez (then Elisabeth Sutherland), who Davis became acquainted with. Other supporters included exiled members of the African National Congress and young members of the Tanzanian mission to the United Nations. On the Friday afternoon of March 19, 1965, some 600 demonstrators marched on Chase Manhattan's offices, with 43 arrested, in what was SDS's first act of civil disobedience.

Davis returned to California in early 1965, arriving in the Bay Area during the transformation of the Free Speech Movement into the Vietnam Day Committee. His only subsistence for the next six months was money earned by selling literature sent to him by the SDS national office. The demand for radical literature by students in the Bay Area was enough that Davis could afford to rent a derelict house with no electricity. While couch surfing in the homes of academics, he became aware of Herbert Marcuse, who was lauded by the organizers of the Free Speech Movement. Davis had struggled to understand any of Marcuse's One-Dimensional Man, but opted to write a letter to the respected academic about the accomplishments and motives of SDS. Marcuse responded, but was critical, suggesting that SDS was only serving to advance Lyndon B. Johnson's war on poverty, and that the organization should seek a more oppositional approach. While in Oakland, Davis burned his draft card in protest of Johnson's intervention in the Dominican Republic.

in June of 1965, after burning his draft card, Davis was sent by the national committee to Los Angeles, where he was ordered to assist in organizing protestors against the construction of the 210 freeway through a historically Black neighborhood in Pasadena. Davis and other SDS members also organized weekly meetings to spread awareness about the draft on local campuses. Working in South Los Angeles, he befriended Levi Kingston, a radicalized sailor from the Merchant Marine. Kingston and Davis worked together organizing draft resistance and doing draft counseling. Kingston later organized a Black draft resistance organization, the Freedom Draft Movement, and remained close friends with Davis for the rest of his life. Davis met his first wife in SDS, who had returned from the 1964 "Freedom Summer" in Mississippi trying to organize tugboat crews. In his time as the Southern California regional organizer, Davis also organized protests against Dow Chemical and their manufacture of napalm used in the Vietnam War, and was arrested several times.

In 1966, 19-year-old Davis, characterized as a "draft card-burning SDS leader," debated actor Kirk Douglas on Melvin Belli's talk show. The section of an article in the Los Angeles Times on the debate was titled Outtalked by 19-Year-Old. Davis was described "...to have much less trouble stating his case then either Belli or Douglas." while Douglas "...was having some difficulty being articulate on his own behalf." In his recollection on the appearance, Davis, the first to be on, was confronted by Douglas as he was leaving the studio. Douglas allegedly called him a "commie dupe." Davis responded by telling Douglas that he admired his appearance in Paths of Glory, but questioned why the actor would star in an anti-war film while serving as a goodwill ambassador for the Johnson administration in Southeast Asia. According to Davis, Douglas was "speechless."

In 1967, Davis briefly left Los Angeles to organize for SDS in Texas, and lived in Austin. While in Texas, Davis sought out the populist news editor Archer Fullingham. At the time, Davis was still wary of Marxism and the number of his friends who were becoming Marxists, and instead was interested in the idea of reviving the Populist Party. He approached Fullingham at his residence in Kountze, and proposed the idea to the editor, suggesting that Fullingham could be the leader of the party. According to Davis, Fullingham rebuked him, calling him "...one of the dumbest piss-ants I've ever met," and suggested Davis "figure out this stuff for yourself."

In late 1967 and 1968, Davis returned to Los Angeles and joined the Southern California District of the Communist Party, headed by Dorothy Healey, in solidarity with their stand against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. He left SDS after the 1969 "Days of Rage," and looked back on the achievements of the movement with ambivalence.

His education was punctuated by stints as a meat cutter, truck driver, and a Congress of Racial Equality and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) activist. At 28, Davis returned to college, studying economics and history at the University of California, Los Angeles on a union scholarship. Davis earned his BA and MA degrees, but did not complete the PhD program in history.

Career

Davis was a 1996–1997 Getty Scholar at the Getty Research Institute and received a MacArthur Fellowship Award in 1998. He won the Lannan Literary Award for Nonfiction in 2007.

Davis was Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Department of Creative Writing at the University of California, Riverside, and an editor of the New Left Review. Davis taught urban theory at the Southern California Institute of Architecture and at Stony Brook University before he secured a position at University of California, Irvine's history department. He also contributed to the British monthly Socialist Review, the organ of the British Socialist Workers Party. As a journalist and essayist, Davis wrote for a number of well-known publications, including The Nation, The New Left Review, Jacobin, and the UK's New Statesman.

Davis was a self-defined international socialist and "Marxist-Environmentalist". He wrote in the tradition of socialists/architects/regionalism advocates such as Lewis Mumford and Garrett Eckbo, whom he cited in Ecology of Fear. His early book, Prisoners of the American Dream, was an important contribution to the Marxist study of U.S. history, political economy, and the state, as well as to the doctrine of revolutionary integrationism.

Davis was also the author of two fiction books for young adults: Land of the Lost Mammoths and Pirates, Bats and Dragons.

Personal life and death

Davis was married to Mexican artist and professor Alessandra Moctezuma and lived in San Diego, California. Prior to his marriage to Moctezuma, he had been married and divorced four times. He had two children with Moctezuma, one child with his fourth wife Sophie Spalding, and one child with his third wife Brigid Loughran.

Davis was diagnosed with cancer in 2020. In a July 25, 2022, story in The Los Angeles Times, Davis said, "I'm in the terminal stage of metastatic esophageal cancer but still up and around the house...But I guess what I think about the most is that I'm just extraordinarily furious and angry. If I have a regret, it's not dying in battle or at a barricade as I've always romantically imagined — you know, fighting." He died from esophageal cancer on October 25, 2022, at age 76.

Awards and honors

- 1991: Deutscher Memorial Prize, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles

- 1996–1997: Getty Scholar at the Getty Research Institute

- 1998: MacArthur Fellowship

- 2002: World History Association Book Prize, Late Victorian Holocausts

- 2007: Lannan Literary Award for Nonfiction

Works

Books

Nonfiction

- Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the U.S. Working Class (1986, 1999, 2018)

- City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (1990, 2006)

- Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster (1998)

- Casino Zombies: True Stories From the Neon West (1999, German only)

- Magical Urbanism: Latinos Reinvent the U.S. Big City (2000)

- Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World (2001)

- The Grit Beneath the Glitter: Tales from the Real Las Vegas, edited with Hal Rothman (2002)

- Dead Cities, And Other Tales (2003)

- Under the Perfect Sun: The San Diego Tourists Never See, with Jim Miller and Kelly Mayhew (2003)

- The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of Avian Flu (2005)

- Planet of Slums: Urban Involution and the Informal Working Class (2006)

- No One Is Illegal: Fighting Racism and State Violence on the U.S.-Mexico Border, with Justin Akers Chacon (2006)

- Buda's Wagon: A Brief History of the Car Bomb (2007)

- In Praise of Barbarians: Essays against Empire (2007)

- Evil Paradises: Dreamworlds of Neoliberalism, edited with Daniel Bertrand Monk (2007)

- Be Realistic: Demand the Impossible (2012)

- Old Gods, New Enigmas: Marx's Lost Theory (2018)

- Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties, co-authored by Jon Wiener (2020)

Fiction

- Land of the Lost Mammoths (2003)

- Pirates, Bats, and Dragons (2004)

See also

In Spanish: Mike Davis (sociólogo) para niños

In Spanish: Mike Davis (sociólogo) para niños