Mary Baker Eddy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mary Baker Eddy

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Mary Morse Baker

July 16, 1821 Bow, New Hampshire, U.S.

|

| Died | December 3, 1910 (aged 89) Newton, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts |

| Other names | Mary Baker Glover, Mary Patterson, Mary Baker Glover Eddy, Mary Baker G. Eddy |

| Known for | Founder of Christian Science |

|

Notable work

|

Science and Health (1875) |

| Spouse(s) |

George Washington Glover

(m. 1843; div. 1844)Daniel Patterson

(m. 1853; div. 1873)Asa Gilbert Eddy

(m. 1877; died 1882) |

| Children | George Washington Glover II |

| Parent(s) | Mark Baker (father) Abigail Ambrose Baker (mother) |

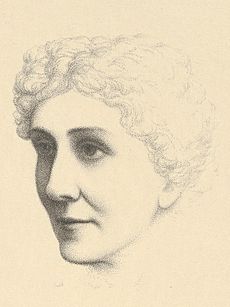

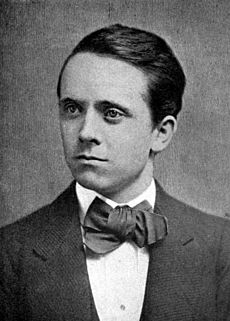

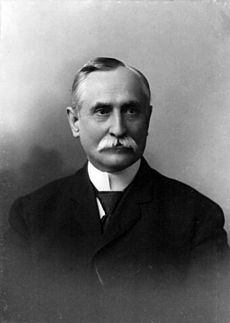

Mary Baker Eddy (née Baker; July 16, 1821 – December 3, 1910) was an American religious leader and author who founded The Church of Christ, Scientist, in New England in 1879. She also founded The Christian Science Monitor, a Pulitzer Prize-winning secular newspaper, in 1908, and three religious magazines: the Christian Science Sentinel, The Christian Science Journal, and The Herald of Christian Science. She wrote numerous books and articles, the most notable of which was Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, which had sold over nine million copies as of 2001.

Members of The First Church of Christ, Scientist consider Eddy the "discoverer" of Christian Science, and adherents are therefore known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science. The church is sometimes informally known as the Christian Science church.

Eddy was named one of the "100 Most Significant Americans of All Time" in 2014 by Smithsonian Magazine, and her book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures was ranked as one of the "75 Books by Women Whose Words Have Changed the World" by the Women's National Book Association.

Contents

Early life

Bow, New Hampshire

Family

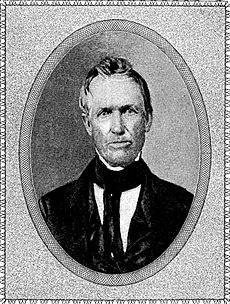

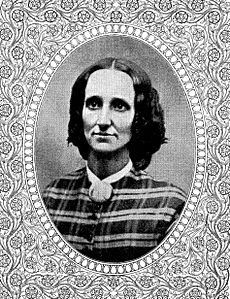

Eddy was born Mary Morse Baker in a farmhouse in Bow, New Hampshire, to farmer Mark Baker (d. 1865) and his wife Abigail Barnard Baker, née Ambrose (d. 1849). Eddy was the youngest of the Bakers' six children: boys Samuel Dow (1808), Albert (1810), and George Sullivan (1812), followed by girls Abigail Barnard (1816), Martha Smith (1819), and Mary Morse (1821).

Mark Baker was a strongly religious man from a Protestant Congregationalist background, a firm believer in the final judgment and eternal damnation, according to Eddy. McClure's magazine published a series of articles in 1907 that were highly critical of Eddy, stating that Baker's home library had consisted of the Bible. Eddy responded that this was untrue and that her father had been an avid reader. According to Eddy, her father had been a justice of the peace at one point and a chaplain of the New Hampshire State Militia. He developed a reputation locally for being disputatious; one neighbor described him as "[a] tiger for a temper and always in a row." McClure's described him as a supporter of slavery and alleged that he had been pleased to hear about Abraham Lincoln's death. Eddy responded that Baker had been a "strong believer in States' rights, but slavery he regarded as a great sin."

The Baker children inherited their father's temper, according to McClure's; they also inherited his good looks, and Eddy became known as the village beauty. Life was nevertheless spartan and repetitive. Every day began with lengthy prayer and continued with hard work. The only rest day was the Sabbath.

Health

Eddy and her father reportedly had a volatile relationship. Ernest Sutherland Bates and John V. Dittemore wrote in 1932, relying on the Cather and Milmine history of Eddy (but see below), that Baker sought to break Eddy's will with harsh punishment, although her mother often intervened; in contrast to Mark Baker, Eddy's mother was described as devout, quiet, light-hearted, and kind. Eddy experienced periods of sudden illness, perhaps in an effort to control her father's attitude toward her. Those who knew the family described her as suddenly falling to the floor, writhing and screaming, or silent and apparently unconscious, sometimes for hours.

Gillian Gill wrote in 1998 that Eddy was often sick as a child and appears to have suffered from an eating disorder, but reports may have been exaggerated concerning hysterical fits. Eddy described her problems with food in the first edition of Science and Health (1875). She wrote that she had suffered from chronic indigestion as a child and, hoping to cure it, had embarked on a diet of nothing but water, bread, and vegetables, at one point consumed just once a day: "Thus we passed most of our early years, as many can attest, in hunger, pain, weakness, and starvation."

Eddy experienced near invalidism as a child and most of her life until her discovery of Christian Science. Like most life experiences, it formed her lifelong, diligent research for a remedy from almost constant suffering. Eddy writes in her autobiography, "From my very childhood I was impelled by a hunger and thirst after divine things, — a desire for something higher and better than matter, and apart from it, — to seek diligently for the knowledge of God as the one great and ever-present relief from human woe." She also writes there, "I wandered through the dim mazes of materia medica, till I was weary of 'scientific guessing,' as it has been well called. I sought knowledge from the different schools, — allopathy, homeopathy, hydropathy, electricity, and from various humbugs, — but without receiving satisfaction."

Tilton, New Hampshire

In 1836 when Eddy was about 14-15, she moved with her family to the town of Sanbornton Bridge, New Hampshire, approximately twenty miles (32 km) north of Bow. Sanbornton Bridge would subsequently be renamed in 1869 as Tilton.

Ernest Bates and John Dittemore write that Eddy was not able to attend Sanbornton Academy when the family first moved there but was required instead to start at the district school (in the same building) with the youngest girls. She withdrew after a month because of poor health, then received private tuition from the Reverend Enoch Corser. She entered Sanbornton Academy in 1842.

She was received into the Congregational church in Tilton on July 26, 1838, when she was 17, according to church records published by McClure's in 1907. Eddy had written in her autobiography in 1891 that she was 12 when this happened, and that she had discussed the idea of predestination with the pastor during the examination for her membership; this may have been an attempt to reflect the story of a 12-year-old Jesus in the Temple. She wrote in response to the McClure's article that the date of her church membership may have been mistaken by her.

Marriage, widowhood

Eddy was badly affected by four deaths in the 1840s. She regarded her brother Albert as a teacher and mentor, but he died in 1841. In 1844, her first husband George Washington Glover (a friend of her brother Samuel) died after six months of marriage. They had married in December 1843 and set up home in Charleston, South Carolina, where Glover had business, but he died of yellow fever in June 1844 while living in Wilmington, North Carolina. Eddy was with him in Wilmington, six months pregnant. She had to make her way back to New Hampshire, 1,400 miles (2,300 km) by train and steamboat, where her only child George Washington II was born on September 12 in her father's home.

Her husband's death, the journey back, and the birth left her physically and mentally exhausted, and she ended up bedridden for months. She tried to earn a living by writing articles for the New Hampshire Patriot and various Odd Fellows and Masonic publications. She also worked as a substitute teacher in the New Hampshire Conference Seminary, and ran her own kindergarten for a few months in 1846, apparently refusing to use corporal punishment.

Then her mother died in November 1849. Eddy wrote to one of her brothers: "What is left of earth to me!" Her mother's death was followed three weeks later by the death of her fiancé, lawyer John Bartlett. In 1850, Eddy wrote, her son was sent away to be looked after by the family's nurse; he was four years old by then. Sources differ as to whether Eddy could have prevented this. It was difficult for a woman in her circumstances to earn money and, according to the legal doctrine of coverture, women in the United States during this period could not be their own children's guardians. When their husbands died, they were left in a legally vulnerable position.

Mark Baker remarried in 1850; his second wife Elizabeth Patterson Duncan (d. June 6, 1875) had been widowed twice, and had some property and income from her second marriage. Baker apparently made clear to Eddy that her son would not be welcome in the new marital home.

George was sent to stay with various relatives, and Eddy decided to live with her sister Abigail. Abigail apparently also declined to take George, then six years old. Eddy married again in 1853. Her second husband, Daniel Patterson, was a dentist and apparently said that he would become George's legal guardian; but he appears not to have gone ahead with this, and Eddy lost contact with her son when the family that looked after him, the Cheneys, moved to Minnesota, and then her son several years later enlisted in the Union army during the Civil War.

Study with Phineas Quimby

Mesmerism had become popular in New England; and on October 14, 1861, Eddy's husband at the time, Dr. Patterson, wrote to mesmerist Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, who reportedly cured people without medicine, asking if he could cure his wife. Quimby replied that he had too much work in Portland, Maine, and that he could not visit her, but if Patterson brought his wife to him he would treat her. Eddy did not immediately go, instead trying the water cure at Dr. Vail's Hydropathic Institute, but her health deteriorated even further. A year later, in October 1862, Eddy first visited Quimby. She improved considerably, and publicly declared that she had been able to walk up 182 steps to the dome of city hall after a week of treatment. The cures were temporary, however, and Eddy suffered relapses.

Despite the temporary nature of the "cure", she attached religious significance to it, which Quimby did not. She believed that it was the same type of healing that Christ had performed. From 1862 to 1865, Quimby and Eddy engaged in lengthy discussions about healing methods practiced by Quimby and others. She took notes on her own ideas on healing, as well as writing dictations from him and "correcting" them with her own ideas, some of which possibly ended up in the "Quimby manuscripts" that were published later and attributed to him. Despite Quimby not being especially religious, he embraced the religious connotations Eddy was bringing to his work, since he knew his more religious patients would appreciate it.

Phineas Quimby died on January 16, 1866, shortly after Eddy's father.

Quimby wrote extensive notes from the 1850s until his death in 1866. Some of his manuscripts, in his own hand, appear in a collection of his writings in the Library of Congress, but far more common was that the original Quimby drafts were edited and rewritten by his copyists. The transcriptions were heavily edited by those copyists to make them more readable. Rumors of Quimby "manuscripts" began to circulate in the 1880s when Julius Dresser began accusing Eddy of stealing from Quimby. Quimby's son, George, who disliked Eddy, did not want any of the manuscripts published, and kept what he owned away from the Dressers until after his death. In 1921, Julius's son, Horatio Dresser, published various copies of writings that he entitled The Quimby Manuscripts to support these claims, but left out papers that didn't serve his view. Further complicating the matter is that, as stated above, no originals of most of the copies exist; and according to Gill, Quimby's personal letters, which are among the items in his own handwriting, "eloquently testify to his incapacity to spell simple words or write a simple, declarative sentence. Thus there is no documentary proof that Quimby ever committed to paper the vast majority of the texts ascribed to him, no proof that he produced any text that someone else could, even in the loosest sense, 'copy.'" In addition, it has been averred that the dates given to the papers seem to be guesses made years later by Quimby's son, and although critics have claimed Quimby used terms like "science of health" in 1859 before he met Eddy, the alleged lack of proper dating in the papers makes this impossible to prove.

According to J. Gordon Melton: "Certainly Eddy shared some ideas with Quimby. She differed with him in some key areas, however, such as specific healing techniques. Moreover, she did not share Quimby's hostility toward the Bible and Christianity."

Fall in Lynn

These contemporaneous news articles both reported on the seriousness of Eddy’s condition. Compare the statement in the Register, “It is feared she will not recover” and the statement in the Reporter that Eddy’s injuries were “internal” and she was removed to her home “in a very critical condition,” to Cushing’s affidavit 38 years later, in 1904: “I did not at any time declare, or believe, that there was no hope of Mrs. Patterson’s recovery, or that she was in a critical condition.” Cushing's effort to downplay the seriousness of the accident perhaps reached its most extreme point in this letter from Gordon Clark, confirmed Eddy critic and author of The Church of St.

Eddy later filed a claim for money from the city of Lynn for her injury on the grounds that she was "still suffering from the effects of that fall" (though she afterwards withdrew the lawsuit). Gill writes that Eddy's claim was probably made under financial pressure from her husband at the time. Her neighbors believed her sudden recovery to be a near-miracle.

Eddy wrote in her autobiography, Retrospection and Introspection, that she devoted the next three years of her life to biblical study and what she considered the discovery of Christian Science: "I then withdrew from society about three years,--to ponder my mission, to search the Scriptures, to find the Science of Mind that should take the things of God and show them to the creature, and reveal the great curative Principle, --Deity."

Spiritualism

Eddy separated from her second husband Daniel Patterson, after which she boarded for four years with several families in Lynn, Amesbury, and elsewhere.

After she became well known, reports surfaced that Eddy was a medium in Boston at one time. At the time when she was said to be a medium there, she lived some distance away. According to Gill, Eddy knew spiritualists and took part in some of their activities, but was never a convinced believer. For example, she visited her friend Sarah Crosby in 1864, who believed in Spiritualism. According to Sibyl Wilbur, Eddy attempted to show Crosby the folly of it by pretending to channel Eddy's dead brother Albert and writing letters which she attributed to him. In regard to the deception, biographer Hugh Evelyn Wortham commented that "Mrs. Eddy's followers explain it all as a pleasantry on her part to cure Mrs. Crosby of her credulous belief in spiritualism." However, Martin Gardner has argued against this, stating that Eddy was working as a spiritualist medium and was convinced by the messages. According to Gardner, Eddy's mediumship converted Crosby to Spiritualism.

In one of her spiritualist trances to Crosby, Eddy gave a message that was supportive of Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, stating "P. Quimby of Portland has the spiritual truth of diseases. You must imbibe it to be healed. Go to him again and lean on no material or spiritual medium." The paragraph that included this quote was later omitted from an official sanctioned biography of Eddy.

Between 1866 and 1870, Eddy boarded at the home of Brene Paine Clark who was interested in Spiritualism. Seances were often conducted there, but Eddy and Clark engaged in vigorous, good-natured arguments about them. Eddy's arguments against Spiritualism convinced at least one other who was there at the time—Hiram Crafts—that "her science was far superior to spirit teachings." Clark's son George tried to convince Eddy to take up Spiritualism, but he said that she abhorred the idea. According to Cather and Milmine, Mrs. Richard Hazeltine attended seances at Clark's home, and she said that Eddy had acted as a trance medium, claiming to channel the spirits of the Apostles.

Mary Gould, a Spiritualist from Lynn, claimed that one of the spirits that Eddy channeled was Abraham Lincoln. According to eyewitness reports cited by Cather and Milmine, Eddy was still attending séances as late as 1872. In these later séances, Eddy would attempt to convert her audience into accepting Christian Science. Eddy showed extensive familiarity with Spiritualist practice but denounced it in her Christian Science writings. Historian Ann Braude wrote that there were similarities between Spiritualism and Christian Science, but the main difference was that Eddy came to believe, after she founded Christian Science, that spirit manifestations had never really had bodies to begin with, because matter is unreal and that all that really exists is spirit, before and after death.

Divorce, publishing her work

Eddy divorced Daniel Patterson in 1873. She published her work in 1875 in a book entitled Science and Health (years later retitled Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures) which she called the textbook of Christian Science, after several years of offering her healing method. The first publication run was 1,000 copies, which she self-published. During these years, she taught what she considered the science of "primitive Christianity" to at least 800 people. Many of her students became healers themselves. The last 100 pages of Science and Health (chapter entitled "Fruitage") contains testimonies of people who claimed to have been healed by reading her book. She made numerous revisions to her book from the time of its first publication until shortly before her death.

Marriage to Asa Gilbert Eddy

On January 1, 1877, she married Asa Gilbert Eddy, becoming Mary Baker Eddy in a small ceremony presided over by a Unitarian minister. In 1881, Mary Baker Eddy started the Massachusetts Metaphysical College with a charter from the state which allowed her to grant degrees. In 1882, the Eddys moved to Boston, and Gilbert Eddy died that year.

Alleged influence of Hinduism

In the 24th edition of Science and Health, up to the 33rd edition, Eddy admitted the harmony between Vedanta philosophy and Christian Science. She also quoted certain passages from an English translation of the Bhagavad Gita, but they were later removed. According to Gill, in the 1891 revision Eddy removed from her book all the references to Eastern religions which her editor, Reverend James Henry Wiggin, had introduced.

Other writers, such as Jyotirmayananda Saraswati, have said that Eddy may have been influenced by ancient Hindu philosophy.

Wendell Thomas in Hinduism Invades America (1930) suggested that Eddy may have discovered Hinduism through the teachings of the New England Transcendentalists such as Bronson Alcott.

In regards to the influence of Eastern religions on her discovery of Christian Science, Eddy states in The First Church of Christ, Scientist and Miscellany: "Think not that Christian Science tends towards Buddhism or any other 'ism'. Per contra, Christian Science destroys such tendency."

Building a church

Eddy devoted the rest of her life to the establishment of the church, writing its bylaws, The Manual of The Mother Church, and revising Science and Health. By the 1870s she was telling her students, "Some day I will have a church of my own." In 1879 she and her students established the Church of Christ, Scientist, "to commemorate the word and works of our Master [Jesus], which should reinstate primitive Christianity and its lost element of healing." In 1892 at Eddy's direction, the church reorganized as The First Church of Christ, Scientist, "designed to be built on the Rock, Christ. ... " In 1881, she founded the Massachusetts Metaphysical College, where she taught approximately 800 students between the years 1882 and 1889, when she closed it. Eddy charged her students $300 each for tuition, a large sum for the time.

Her students spread across the country practicing healing, and instructing others. Eddy authorized these students to list themselves as Christian Science Practitioners in the church's periodical, The Christian Science Journal. She also founded the Christian Science Sentinel, a weekly magazine with articles about how to heal and testimonies of healing.

In 1888, a reading room selling Bibles, her writings and other publications opened in Boston. This model would soon be replicated, and branch churches worldwide maintain more than 1,200 Christian Science Reading Rooms today.

In 1894 an edifice for The First Church of Christ, Scientist was completed in Boston (The Mother Church). In the early years Eddy served as pastor. In 1895 she ordained the Bible and Science and Health as the pastor.

Eddy founded The Christian Science Publishing Society in 1898, which became the publishing home for numerous publications launched by her and her followers. In 1908, at the age of 87, she founded The Christian Science Monitor, a daily newspaper. She also founded the Christian Science Journal in 1883, a monthly magazine aimed at the church's members and, in 1898, the Christian Science Sentinel, a weekly religious periodical written for a more general audience, and the Herald of Christian Science, a religious magazine with editions in many languages.

Malicious animal magnetism

The opposite of Christian Science mental healing was the use of mental powers for destructive or selfish reasons – for which Eddy used terms such as animal magnetism, hypnotism, or mesmerism interchangeably. In 1882 Eddy publicly claimed that her last husband, Asa Gilbert Eddy, had died of malicious animal magnetism.

The belief in malicious animal magnetism "remains a part of the doctrine of Christian Science." Christian Scientists use it as a specific term for a hypnotic belief in a power apart from God.

Use of medicine

Eddy recommended to her son that, rather than go against the law of the state, he should have her grandchildren vaccinated.

Eddy used glasses for several years for very fine print, but later dispensed with them almost entirely. She found she could read fine print with ease. In 1907 Arthur Brisbane interviewed Eddy. At one point he picked up a periodical, selected at random a paragraph, and asked Eddy to read it. According to Brisbane, at the age of eighty six, she read the ordinary magazine type without glasses. Towards the end of her life she was frequently attended by physicians.

Death

Eddy died of pneumonia on the evening of December 3, 1910, at her home at 400 Beacon Street, in the Chestnut Hill section of Newton, Massachusetts. Her death was announced the next morning, when a city medical examiner was called in. She was buried on December 8, 1910, at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her memorial was designed by New York architect Egerton Swartwout (1870–1943). Hundreds of tributes appeared in newspapers around the world, including The Boston Globe, which wrote, "She did a wonderful—an extraordinary work in the world and there is no doubt that she was a powerful influence for good."

Legacy

The influence of Eddy's writings has reached outside the Christian Science movement. Richard Nenneman wrote "the fact that Christian Science healing, or at least the claim to it, is a well-known phenomenon, was one major reason for other churches originally giving Jesus' command more attention. There are also some instances of Protestant ministers using the Christian Science textbook [Science and Health], or even the weekly Bible lessons, as the basis for some of their sermons."

The Christian Science Monitor, which was founded by Eddy as a response to the yellow journalism of the day, has gone on to win seven Pulitzer Prizes and numerous other awards.

In 1945 Bertrand Russell wrote that Pythagoras may be described as "a combination of Einstein and Mrs. Eddy".

A bronze memorial relief of Eddy by Lynn sculptor Reno Pisano was unveiled in December, 2000, at the corner of Market Street and Oxford Street in Lynn near the site of her fall in 1866.

Residences

In 1921, on the 100th anniversary of Eddy's birth, a 100-ton (in rough) and 60–70 tons (hewn) pyramid with a 121 square foot (11.2 m2) footprint was dedicated on the site of her birthplace in Bow, New Hampshire. A gift from James F. Lord, it was dynamited in 1962 by order of the church's Board of Directors. Also demolished was Eddy's former home in Pleasant View, as the Board feared that it was becoming a place of pilgrimage. Eddy is featured on a New Hampshire historical marker (number 105) along New Hampshire Route 9 in Concord.

Several of Eddy's homes are owned and maintained as historic sites by the Longyear Museum and may be visited (the list below is arranged by date of her occupancy):

- 1855–1860 – Hall's Brook Road, North Groton, New Hampshire

- 1860–1862 – Stinson Lake Road, Rumney, New Hampshire

- 1865–1866 – 23 Paradise Road, Swampscott, Massachusetts

- 1868,1870 – 277 Main Street, Amesbury, Massachusetts

- 1868–1870 – 133 Central Street, Stoughton, Massachusetts

- 1875–1882 – 8 Broad Street, Lynn, Massachusetts (NRHP-listed in 2021)

- 1889–1892 – 62 North State Street, Concord, New Hampshire (NRHP-listed in 1982)

- 1908–1910 – 400 Beacon Street, Chestnut Hill, Newton, Massachusetts (NRHP-listed in 1986)

-

23 Paradise Road, Swampscott, Massachusetts

-

277 Main Street, Amesbury, Massachusetts

-

133 Central Street, Stoughton, Massachusetts

-

8 Broad Street, Lynn, Massachusetts

-

400 Beacon Street, Chestnut Hill, Newton, Massachusetts

See also

In Spanish: Mary Baker Eddy para niños

In Spanish: Mary Baker Eddy para niños