Martian canals facts for kids

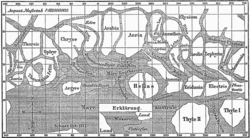

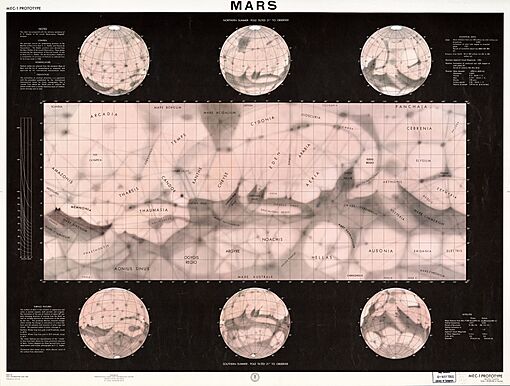

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was erroneously believed that there were "canals" on the planet Mars. These were a network of long straight lines in the equatorial regions from 60° north to 60° south latitude on Mars, observed by astronomers using early telescopes without photography.

They were first described by the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli during the opposition of 1877, and confirmed by later observers. Schiaparelli called these canali ("channels"), which was mis-translated into English as "canals". The Irish astronomer Charles E. Burton made some of the earliest drawings of straight-line features on Mars, although his drawings did not match Schiaparelli's.

Around the turn of the century there was even speculation that they were engineering works, irrigation canals constructed by a civilization of intelligent aliens indigenous to Mars. By the early 20th century, improved astronomical observations revealed the "canals" to be an optical illusion, and modern high-resolution mapping of the Martian surface by spacecraft shows no such features.

Supposed "discoveries"

The Italian word canale (plural canali) can mean "canal", "channel", "duct" or "gully". The first person to use the word canale in connection with Mars was Angelo Secchi in 1858, although he did not see any straight lines and applied the term to large features—for example, he used the name "Canale Atlantico" for what later came to be called Syrtis Major Planum. The canals were named by Schiaparelli and others after both real and legendary rivers of various places on Earth, or the mythological underworld.

At this time in the late 19th century, astronomical observations were made without photography. Astronomers had to stare for hours through their telescopes, waiting for a moment of still air when the image was clear, and then draw a picture of what they had seen. Astronomers believed at the time that Mars had a relatively substantial atmosphere. They knew that the rotation period of Mars (the length of its day) was almost the same as Earth's, and they knew that Mars' axial tilt was also almost the same as Earth's, which meant it had seasons in the astronomical and meteorological sense. They could also see Mars' polar ice caps shrinking and growing with these changing seasons. The similarities with Earth led them to interpret darker albedo features (for instance Syrtis Major) on the lighter surface as oceans. By the late 1920s, however, it was known that Mars is very dry and has a very low atmospheric pressure.

In 1889, American astronomer Charles A. Young reported that Schiaparelli's canal discovery of 1877 had been confirmed in 1881, though new canals had appeared where there had not been any before, prompting "very important and perplexing" questions as to their origin.

During the favourable opposition of 1892, W. H. Pickering observed numerous small circular black spots occurring at every intersection or starting-point of the "canals". Many of these had been seen by Schiaparelli as larger dark patches, and were termed seas or lakes; but Pickering's observatory was at Arequipa, Peru, about 2400 meters above the sea, and with such atmospheric conditions as were, in his opinion, equal to a doubling of telescopic aperture. They were soon detected by other observers, especially by Lowell.

During the oppositions of 1892 and 1894, seasonal color changes were reported. As the polar snows melted the adjacent seas appeared to overflow and spread out as far as the tropics, and were often seen to assume a distinctly green colour. At this time (1894) it began to be doubted whether there were any seas at all on Mars. Under the best conditions, these supposed 'seas' were seen to lose all trace of uniformity, their appearance being that of a mountainous country, broken by ridges, rifts, and canyons, seen from a great elevation. These doubts soon became certainties, and it is now universally agreed that Mars possesses no permanent bodies of surface water.

Contemporary doubts and definitive debunk

Other observers disputed the notion of canals. The influential observer Eugène Antoniadi used the 83 cm (32.6 inch) aperture telescope at Meudon Observatory during the 1909 opposition of Mars and saw no canals, the outstanding photos of Mars taken at the new Baillaud dome at the Pic du Midi observatory also brought formal discredit to the Martian canals theory in 1909, and the notion of canals began to fall out of favor. Around this time spectroscopic analysis also began to show that no water was present in the Martian atmosphere. However, as of 1916 Waldemar Kaempffert (editor of Scientific American and later Popular Science Monthly) was still vigorously defending the Martian canals theory against skeptics.

In 1907 the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace published the book Is Mars Habitable? that severely criticized Lowell's claims. Wallace's analysis showed that the surface of Mars was almost certainly much colder than Lowell had estimated, and that the atmospheric pressure was too low for liquid water to exist on the surface. He also pointed out that several recent efforts to find evidence of water vapor in the Martian atmosphere with spectroscopic analysis had failed. He concluded that complex life was impossible, let alone the planet-girding irrigation system claimed by Lowell.

The existence of Martian canals was still controversial even at the dawn of the Space Race. In 1965, the Sourcebook on the space sciences said that "Although there is no unanimous opinion concerning the existence of the canals, most astronomers would probably agree that there are apparently linear (or approximately linear) markings, perhaps 40 to 160 kilometers (25 to 100 miles) or more across and of considerable length." Later in the same year, the arrival of the United States' Mariner 4 spacecraft debunked for good the idea that Mars could be inhabited by higher forms of life, or that any canal features existed. It took pictures revealing impact craters and a generally barren Martian landscape, with a surface atmospheric pressure of 4.1 to 7.0 millibars (410 to 700 pascals), 0.4% to 0.7% of Earth atmospheric pressure, and daytime temperatures of −100 degrees Celsius were measured. No magnetic field, nor Martian radiation belts were detected.

As early as 1903, Joseph Edward Evans and Edward Maunder conducted visual experiments using schoolboy volunteers that demonstrated how the canals could arise as an optical illusion. This is because when a poor-quality telescope views many point-like features (e.g. sunspots or craters) they appear to join up to form lines. Based on his own experiments, Lowell's assistant, A. E. Douglass, was led to explain the observations in essentially psychological terms. In hindsight, William Kenneth Hartmann, a Mars imaging scientist from the 1960s to the 2000s, hypothesized that the "canals" were streaks of dust caused by wind on the leeward side of mountains and craters.

See also

In Spanish: Canales de Marte para niños

In Spanish: Canales de Marte para niños

- Classical albedo features on Mars

- Face on Mars

- History of Mars observation

- Life on Mars

- Lineae

- Outflow channel

- Solis Lacus

- Valley networks (Mars)

- Water on Mars