Maria P. Williams facts for kids

Maria Priscilla Thurston Williams (1866–1932) is credited as the first Black woman film producer for the silent crime drama The Flames of Wrath in 1923. A one-time school teacher, Williams had a history of activism, independence and interest in the liberal arts, which led her first to newspapers, then to film production, script-writing and acting and, finally, to memoir with her 1916 book My Work and Public Sentiment, in which she identified herself as a national organizer and speaker with the Good Citizens League, and stated that ten percent of the proceeds would go to suppressing crime among African Americans.

History

Williams served as editor-in-chief (1891–1894) of the Kansas City weekly New Era. This spurred her to seek greater independence by founding, writing and editing her own newspaper, the Women's Voice (1896–1900), "sponsored by the 'colored women's auxiliary' of the Republican party; the paper was described as having "many pleasant things to say on a choice of timely topics.'" In 1916, Williams went on to publish her memoir.

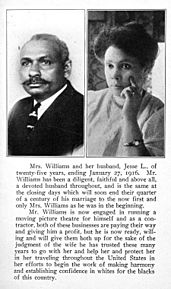

In 1916, Williams also married entrepreneur Jesse L. Williams, who owned a movie theater among several other businesses in Kansas City. The pair co-managed the movie theater, which gave the couple experience in the distribution and release of films for African-American audiences. With Williams serving both as the company's secretary and treasurer, the couple went on to co-found Western Film Producing Co. and Booking Exchange, and Williams went on to write the script for Flames of Wrath, produce a film from the script and play the role of prosecuting attorney in the five-reel film. That same year, Williams' husband died, and she soon went on to marry another man. She died in 1932, after being "called away from her home by a stranger who requested help for his ill brother. She was found shot to death on the side of a road several miles from her home. The murder remains unsolved."

Ironically, the plot for ''Flames of Wrath'' concerns the investigation of a murder after a robbery. Aimee Dixon Anthony stated that Williams could also reasonably be considered the film's director, given how undifferentiated the two roles were at that time. That distinction is typically granted to Tressie Souders, however, who served as director of 1922's A Woman's Error.

See also

Black women film pioneers

- A website for Sisters in Cinema Documentary: A History of African American Women Feature Film Directors

- The Atlantic on When Hollywood's Power Players Were Women

- Greenlight Women on Celebrating Black Female Directors and Actresses over 40

Early Black film