Magnús Eiríksson facts for kids

- Magnús Eiríksson was also the Old Norse name of Magnus IV of Sweden.

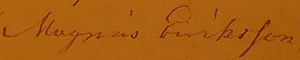

Magnús Eiríksson (22 June 1806 in Skinnalón (Norður-Þingeyjarsýsla), Iceland – 3 July 1881 in Copenhagen, Denmark) was an Icelandic theologian and a contemporary critic of Søren Aabye Kierkegaard (1813–1855) and Hans Lassen Martensen (1808–1884) in Copenhagen.

Due to his very critical attitude towards the church dogma, especially the dogmas of the Trinity of God and the Divinity of Christ, in contrast to which he stressed (at least in his late work) the essential unity of God and the leadership of Jesus (merely) as prophet and teacher, Eiríksson often was labeled as a “pioneer” or “precursor” to the Unitarian movement in Denmark.

Contents

Childhood and study of theology

Magnús Eiríksson was born the eldest of the five children of Eiríkur Grímsson († 1812), a farmer, and Þorbjörg Stephánsdóttir († 1841), a pastor's daughter, in Skinnalón, Norður-Þingeyjarsýsla, on the northeastern tip of Iceland. In 1831, he left for Copenhagen to take the university entrance examination. He then remained in Copenhagen until his death in 1881. Eiríksson studied theology at the University of Copenhagen, where he was deeply influenced by Professor Henrik Nicolai Clausen (1793–1877), who represented a form of theological rationalism which appealed to him. After obtaining his degree in 1837, Eiríksson became a tutor to theology students (manuduktør), among whom he enjoyed considerable popularity.

Eiríksson’s relations to Martensen and Kierkegaard (1844-1850)

Eiríksson as an opponent of Martensen

Unlike to Clausen's rationalism, Eiríksson was very critical to H. L. Martensen's speculative theology, which he violently attacked in various publications from 1844 to 1850. His basic point was that faith was based on reason, and “only that which can be accepted by reason can and should be accepted by faith”. Martensen refused to become involved in polemic with Eiríksson, and remained completely silent. This silence so irritated Eiríksson that in 1847 he wrote a letter to King Christian VII denouncing Martensen's silence as “inexcusable, dishonest and dishonorable” and demanding that Martensen be relieved of his professorship at Copenhagen University. His accusations against Martensen were violent and uncontrolled, but at the same time he also attacked the Government's alleged absolutism. As a result, the public prosecutor was ordered to institute proceedings against him. With the king's death in 1848, however, and the general amnesty which accompanied his successor, Frederik VII's, accession to the throne, these were dropped. Eiríksson's attack on Martensen harmed himself most, particularly financially, as the students, in sympathy with their famous professor, stopped using Eiríksson as a tutor. His financial situation became particularly bad, and he (at least) twice wrote to Søren Kierkegaard asking for help, but Kierkegaard refused.

Eiríksson as an unwelcome ally of Kierkegaard

In his attack on speculative theology, and especially on Martensen's, Eiríksson thought he had an ally in Søren Kierkegaard and Kierkegaard's Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1846) supported him in this claim. Kierkegaard, however, vigorously protested against this “unauthorized acknowledgment” of his writings by “that raging Roland” and accused Eiríksson of attributing to him motives of which there is not a trace in the book. Regarding Eiríksson's efforts to get Martensen dismissed, Kierkegaard comments: “And with the violence and force of the Devil he has involved my ‘Concluding Unscientific Postscript’ in his ... campaign. ... I do not know either whether M.E. has read the book. But if he has read it, I do know that he has absolutely, mendaciously and presumptuously misunderstood it” In 1850 Eiríksson published pseudonymously [Theophilus Nicolaus] his book Er Troen et Paradox og ‘i Kraft af det Absurde’? [Is Faith a Paradox and ‘by Virtue of the Absurd’?] where he criticized Kierkegaard's account of faith. Eiríksson declared that faith must not be made into a paradox, for “when faith is genuine and strong, it has its firm base and deep root in the immediate intellectual faculty in man, which we call reason.” Faith understood as a paradox “annuls and destroys all independent thought.” In his (albeit unpublished) answer to Theophilus Nicolaus, alias Eiríksson, Kierkegaard claims that Eiríksson has completely misunderstood his works and quite overlooked their main concern. In his zeal to prove that faith was not in any way a paradox, Eiríksson – according to Kierkegaard – had lost Christianity: “Both the paradox and Christianity, jointly and separately, vanished completely”. Therefore, instead of inviting Kierkegaard to “take up that matter of the paradox” again, Eiríksson should himself first take up Christianity which, in his zeal, he had lost.

The periods of silence (1850–1863) and harsh criticism of Christian dogmatic theology (1863-74)

With the exception of a few articles Eiríksson remained silent in the period 1850–1863. In these years he went through a spiritual crisis. He came to see clearly that the Church's doctrine that God became man in and through Jesus Christ had to be rejected, for it would have the result of leading to the deification of man. German biblical criticism and, in particular, the influence of the Tübingen School caused him to break radically with Johannine and Pauline theology. In Jøder og Christne [Jews and Christians] (1871) Eiríksson drew the ultimate conclusion and explained that Judaism, which in his terminology meant an immediate childlike trust in God, was the only true religion. Jesus had only wanted to purify Judaism, and it is to purified Judaism that we must return.

In the face of the continuing silence of "the professionals", a number of laypeople with religious interests, such as the religious author Andreas Daniel Pedrin (1823–1891) and the postal supervisor and author Jørgen Christian Theodor Faber (1824–1886), felt called to take a public stand against Eiríksson's views. In Denmark, on the whole, Eiríksson's late writings provoked a wide spectrum of reactions. These ranged in tone from radical rejection at one extreme, to open professions of sympathy for Eiríksson and his message at the other end. In his native Iceland, however, Eiríksson's reception was almost uniformly harsh. There his much-discussed book The Gospel of John (1863) sparked fierce controversy: not only theologians like Sigurður Melsteð (1819–1895), but also the Catholic priests Jean-Baptiste Baudoin (1831–1875) and Bernard Bernard (1821–1895) felt compelled to take a stand against him. In Sweden, by contrast, Eiríksson's thought found more fertile soil—thanks above all to the "freethinking pastor" Nils Johan Ekdahl (1799–1870), who translated two of Eiríksson's books into Swedish. It is not by chance that, in 1877, Eiríksson's final publications appeared in Swedish newspapers and periodicals–most prominently in the journal Sanningssökaren ["The Truth-Seeker"].

Had Eiríksson's supporters and friends not arranged a modest annuity to supplement his state pension, Eiríksson would surely have suffered acute financial distress during his final years. In mid-1878, Eiríksson was even provided with funds to make a brief return to Iceland, but his failing health made such a visit impossible. After his death on July 3, 1881, at Frederiks Hospital in Copenhagen, Eiríksson's friends set up a mounted bust on his grave in Garnisons Kirkegård.