Khmelnytsky Uprising facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Khmelnytsky Uprising |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Deluge | |||||||||

Entrance of Bohdan Khmelnytsky to Kyiv, Mykola Ivasyuk |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

(till 1657) |

|||||||||

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, or the Khmelnytsky insurrection, was a Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which led to the creation of a Cossack Hetmanate in Ukraine. Under the command of hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the Zaporozhian Cossacks, allied with the Crimean Tatars and local Ukrainian peasantry, fought against Polish domination and Commonwealth's forces. The insurgency was accompanied by mass atrocities committed by Cossacks against the civilian population, especially against the Roman Catholic and Ruthenian Uniate clergy and the Jews, as well as savage reprisals by Jeremi Wiśniowiecki, the voivode (military governor) of the Ruthenian Voivodeship.

The uprising has a symbolic meaning in the history of Ukraine's relationship with Poland and Russia. It ended the Polish Catholic szlachta′s domination over the Ukrainian Orthodox population; at the same time, it led to the eventual incorporation of eastern Ukraine into the Tsardom of Russia initiated by the 1654 Pereiaslav Agreement, whereby the Cossacks would swear allegiance to the tsar while retaining a wide degree of autonomy. The event triggered a period of political turbulence and infighting in the Hetmanate known as the Ruin. The success of the anti-Polish rebellion, along with internal conflicts in Poland, as well as concurrent wars waged by Poland with Russia and Sweden (the Russo-Polish War (1654–1667) and Second Northern War (1655–1660) respectively), ended the Polish Golden Age and caused a secular decline of Polish power during the period known in Polish history as "the Deluge".

Contents

Background

In 1569 the Union of Lublin granted the southern Lithuanian-controlled Ruthenian voivodeships of Volhynia, Podolia, Bracław and Kiev—to the Crown of Poland under the agreement forming the new Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita). The Kingdom of Poland already controlled several Ruthenian lands which formed the voivodeships of Lviv and Belz. The combined lands would be formed into the Lesser Poland Province, Crown of the Kingdom of Poland. Although the local nobility was granted full rights within the Rzeczpospolita, their assimilation of Polish culture alienated them from the lower classes. It was especially important in regard to powerful and traditionally influential great princely families of Ruthenian origins, among them Wiśniowiecki, Czartoryski, Ostrogski, Sanguszko, Zbaraski, Korecki and Zasławski, which acquired even more power and were able to gather more lands, creating huge latifundia. This szlachta, along with the actions of the upper-class Polish magnates, oppressed the lower-class Ruthenians, with the introduction of Counter-Reformation missionary practices and the use of Jewish arendators to manage their estates.

Local Orthodox traditions were also affected from the assumption of ecclesiastical power by the Grand Duchy of Moscow in 1448. The growing Russian state in the north sought to acquire the southern lands of Kievan Rus', and with the fall of Constantinople it began this process by insisting that the Metropolitan of Moscow and All Rus′ was now the primate of the Russian Church.

The pressure of Catholic expansionism culminated with the Union of Brest in 1596, which attempted to retain the autonomy of the Eastern Orthodox churches in present-day Ukraine, Poland and Belarus by aligning themselves with the Bishop of Rome. Many Cossacks were also against the Uniate Church. While all of the people did not unite under one church, the concepts of autonomy were implanted into consciousness of the area and came out in force during the military campaign of Bohdan Khmelnytsky.

Khmelnytsky's role

Born to a noble family, Bohdan Khmelnytsky attended a Jesuit school, probably in Lviv. At the age of 22, he joined his father in the service of the Commonwealth, battling against the Ottoman Empire in the Moldavian Magnate Wars. After being held captive in Constantinople, he returned home as a Registered Cossack, settling in his khutor Subotiv with a wife and several children. He participated in campaigns for Grand Crown Hetman Stanisław Koniecpolski, led delegations to King Władysław IV Vasa in Warsaw and generally was well respected within the Cossack ranks. The course of his life was altered, however, when Aleksander Koniecpolski, heir to hetman Koniecpolski's magnate estate, attempted to seize Khmelnytsky's land. In 1647 Chyhyryn deputy of starosta (head of the local royal administration) Daniel Czapliński openly started to harass Khmelnytsky on behalf of the younger Koniecpolski in an attempt to force him off the land. On two occasions raids were made to Subotiv, during which considerable property damage was done and his son Yurii was badly beaten, until Khmelnytsky moved his family to a relative's house in Chyhyryn. He twice sought assistance from the king by traveling to Warsaw, only to find him either unwilling or powerless to confront the will of a magnate.

Having received no support from Polish officials, Khmelnytsky turned to his Cossack friends and subordinates. The case of a Cossack being unfairly treated by the Poles found a lot of support not only in his regiment but also throughout the Sich. All through the autumn of 1647, Khmelnytsky travelled from one regiment to another and had numerous consultations with different Cossack leaders throughout Ukraine. His activity raised the suspicions of Polish authorities already used to Cossack revolts, and he was promptly arrested. Polkovnyk (colonel) Mykhailo Krychevsky assisted Khmelnytsky in his escape, and with a group of supporters he headed for the Zaporozhian Sich.

The Cossacks were already on the brink of a new rebellion as plans for the new war with the Ottoman Empire advanced by the Polish king Władysław IV Vasa were cancelled by the Sejm. Cossacks were gearing up to resume their traditional and lucrative attacks on the Ottoman Empire (in the first quarter of the 17th century they raided the Black Sea shores almost annually), as they greatly resented being prevented from the pirate activities by the peace treaties between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire. Rumors about the emerging hostilities with "the infidels" were greeted with joy, and the news that there was to be no raiding after all was explosive in itself.

However, the Cossack rebellion might have fizzled in the same manner as the great rebellions of 1637–1638 but for the strategies of Khmelnytsky. Having taken part in the 1637 rebellion, he realized that Cossacks, while having an excellent infantry, could not hope to match the Polish cavalry, which was possibly the best in Europe at the time. However, combining Cossack infantry with Crimean Tatar cavalry could provide a balanced military force and give the Cossacks a chance to beat the Polish army.

Beginning

On January 25, 1648, Khmelnytsky brought a contingent of 400–500 Cossacks to the Zaporizhian Sich and quickly killed the guards assigned by the Commonwealth to protect the entrance. Once at the Sich, his oratory and diplomatic skills struck a nerve with oppressed Ruthenians. As his men repelled an attempt by Commonwealth forces to retake the Sich, more recruits joined his cause. The Cossack Rada elected him Hetman by the end of the month. Khmelnytsky threw most of his resources into recruiting more fighters. He sent emissaries to Crimea, enjoining the Tatars to join him in a potential assault against their shared enemy, the Commonwealth.

By April 1648 word of an uprising had spread throughout the Commonwealth. Either because they underestimated the size of the uprising, or because they wanted to act quickly to prevent it from spreading, the Commonwealth's Grand Crown Hetman Mikołaj Potocki and Field Crown Hetman Marcin Kalinowski sent 3,000 soldiers under the command of Potocki's son, Stefan, towards Khmelnytsky, without waiting to gather additional forces from Prince Jeremi Wiśniowiecki. Khmelnytsky marshalled his forces and met his enemy at the Battle of Zhovti Vody, which saw a considerable number of defections on the field of battle by Registered Cossacks, who changed their allegiance from the Commonwealth to Khmelnytsky. The victory was quickly followed by rout of the Commonwealth's armies at the Battle of Korsuń, which saw both the elder Potocki and Kalinowski captured and imprisoned by the Tatars.

In addition to the loss of significant forces and military leadership, the Polish state also lost King Władysław IV Vasa, who died in 1648, leaving the Crown of Poland leaderless and in disarray at a time of rebellion. The szlachta was on the run from its peasants, their palaces and estates in flames. All the while, Khmelnytsky's army marched westward.

Khmelnytsky stopped his forces at Bila Tserkva and issued a list of demands to the Polish Crown, including raising the number of Registered Cossacks, returning churches taken from the Orthodox faithful and paying the Cossacks for wages, which had been withheld for five years.

News of the peasant uprisings now troubled a nobleman such as Khmelnytsky; however, after discussing information gathered across the country with his advisers, the Cossack leadership soon realized the potential for autonomy was there for the taking. Although Khmelnytsky's personal resentment of the szlachta and the magnates influenced his transformation into a revolutionary, it was his ambition to become the ruler of a Ruthenian nation that expanded the uprising from a simple rebellion into a national movement. Khmelnytsky had his forces join a peasant revolt at the Battle of Pyliavtsi, striking another terrible blow to weakened and depleted Polish forces.

Khmelnytsky was persuaded not to lay siege to Lviv, in exchange for 200,000 red guldens, according to some sources, but Hrushevsky stated that Khmelnytsky did indeed lay siege to the town, for about two weeks. After obtaining the ransom, he moved to besiege Zamość, when he finally heard about the election of the new Polish King, John Casimir II, whom Khmelnytsky favored. According to Hrushevsky John Casimir II sent him a letter in which he informed the Cossack leader about his election and assured him that he would grant Cossacks and all of the Orthodox faith various privileges. He requested for Khmelnytsky to stop his campaign and await the royal delegation. Khmelnytsky answered that he would comply with his monarch's request and then turned back. He made a triumphant entry into Kiev on Christmas Day in 1648, and he was hailed as "the Moses, savior, redeemer, and liberator of the people from Polish captivity... the illustrious ruler of Rus".

In February 1649, during negotiations with a Polish delegation headed by nobleman Adam Kysil in Pereiaslav, Khmelnytsky declared that he was "the sole autocrat of Rus" and that he had "enough power in Ukraine, Podolia, and Volhynia... in his land and principality stretching as far as Lviv, Chełm, and Halych". It became clear to the Polish envoys that Khmelnytsky had positioned himself no longer as simply a leader of the Zaporozhian Cossacks but as that of an independent state and stated his claims to the heritage of the Rus'.

A Vilnius panegyric in Khmelnytsky's honour (1650–1651) explained it: "While in Poland it is King Jan II Casimir Vasa, in Rus it is Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky".

Following the Battles of Zbarazh and Zboriv, Khmelnytsky gained numerous privileges for the Cossacks under the Treaty of Zboriv. When hostilities resumed, however, his forces suffered a massive defeat in 1651 at the Battle of Berestechko, considered to be one of the largest land battles of the 17th century, and they were abandoned by their former allies, the Crimean Tatars. They were forced at Bila Tserkva to accept the Treaty of Bila Tserkva. A year later, in 1652, the Cossacks had their revenge at the Battle of Batih, where Khmelnytsky ordered Cossacks to kill all Polish prisoners and paid Tatars for possession of the prisoners, an event known to as the Batih massacre.

However, the enormous casualties suffered by the Cossacks at Berestechko made the idea of creating an independent state impossible to implement. Khmelnytsky had to decide whether to stay under Polish–Lithuanian influence or ally with the Muscovites.

Tatars' role

The Tatars of the Crimean Khanate, then a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire, participated in the insurrection, seeing it as a source of captives to be sold. Slave raiding sent a large influx of captives to slave markets in Crimea at the time of the Uprising. Ottoman Jews collected funds to mount a concerted ransom effort to gain the freedom of their people.

Aftermath

Within a few months almost all Polish nobles, officials and priests had been wiped out or driven from the lands of present-day Ukraine. The Commonwealth population losses in the uprising exceeded one million. In addition, Jews suffered substantial losses because they were the most numerous and accessible representatives of the szlachta regime.

The uprising began a period in Polish history known as The Deluge (which included the Swedish invasion of the Commonwealth during the Second Northern War of 1655–1660), that temporarily freed the Ukrainians from Polish domination but in a short time subjected them to Russian domination. Weakened by wars, in 1654 Khmelnytsky persuaded the Cossacks to ally with the Russian tsar in the Treaty of Pereyaslav, which led to the Russo-Polish War (1654–1667). When Poland–Lithuania and Russia signed the Truce of Vilna and agreed on an anti-Swedish alliance in 1657, Khmelnytsky's Cossacks supported the invasion of the Commonwealth by Sweden's Transylvanian allies instead. Although the Commonwealth tried to regain its influence over the Cossacks (note the Treaty of Hadiach of 1658), the new Cossack subjects became even more dominated by Russia. The Hetmanate entered a new political situation which was far different than in the Commonwealth, and the church was much more subordinate to the tsar there. Russia had a traditional practice of imprisoning as well as executing Orthodox officials, which was foreign to people from the Commonwealth. With the Commonwealth becoming increasingly weak, Cossacks became more and more integrated into the Russian Empire, with their autonomy and privileges eroded. The remnants of these privileges were gradually abolished in the aftermath of the Great Northern War (1700–1721), in which hetman Ivan Mazepa sided with Sweden. By the time that the last of the partitions of Poland ended the existence of the Commonwealth in 1795, many Cossacks had already left Ukraine to colonise the Kuban and, in process, were russified.

Sources vary as to when the uprising ended. Russian and some Polish sources give the end-date of the uprising as 1654, pointing to the Treaty of Pereyaslav as ending the war; Ukrainian sources give the date as Khmelnytsky's death in 1657; and few Polish sources give the date as 1655 and the Battle of Jezierna or Jeziorna (November 1655). There is some overlap between the last phase of the uprising and the beginning of the Russo-Polish War (1654–1667), as Cossack and Russian forces became allied.

Casualties

Estimates of the death tolls of the Khmelnytsky uprising vary, as do many others from the eras analyzed by historical demography. As better sources and methodology are becoming available, such estimates are subject to continuing revision. Population losses of the entire Commonwealth population in the years 1648–1667 (a period which includes the Uprising, but also the Polish-Russian War and the Swedish invasion) are estimated at 4 million (roughly a decrease from 11 to 12 million to 7–8 million).

Massacres

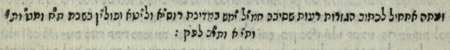

Before the Khmelnytsky uprising, magnates had sold and leased certain privileges to arendators, many of whom were Jewish, who earned money from the collections they made for the magnates by receiving a percentage of an estate's revenue. By not supervising their estates directly, the magnates left it to the leaseholders and collectors to become objects of hatred to the oppressed and long-suffering peasants. Khmelnytsky told the people that the Poles had sold them as slaves "into the hands of the accursed Jews." With this as their battle cry, Cossacks and the peasantry massacred numerous Jewish and Polish–Lithuanian townsfolk, as well as szlachta during the years 1648–1649. Yeven Mezulah, the contemporary 17th-century chronicle by Nathan ben Moses Hannover, an eyewitness, states:

Wherever they found the szlachta, royal officials or Jews, they [Cossacks] killed them all, sparing neither women nor children. They pillaged the estates of the Jews and nobles, burned churches and killed their priests, leaving nothing whole.

Jews

Most Jewish communities in the rebellious Hetmanate were devastated by the uprising and ensuing massacres, though occasionally a Jewish population was spared, notably after the capture of the town of Brody (the population of which was 70% Jewish). According to the book known as History of the Rus, Khmelnytsky's rationale was largely mercantile and the Jews of Brody, which was a major trading centre, were judged to be useful "for turnovers and profits" and thus they were only required to pay "moderate indemnities" in kind. One estimate (1996) reports that 15,000–30,000 Jews were killed or taken captive, and that 300 Jewish communities were completely destroyed. A 2014 estimate puts the number of Jews that died during the national uprising of Ukrainians to 18,000–20,000 people between the years 1648–1649; of these, 3,000–6,000 Jews were killed by Cossacks in Nemirov in May 1648 and 1,500 in Tulczyn in July 1648.

Although many modern sources still give estimates of Jews killed in the uprising at 100,000 or more, others put the numbers killed at between 40,000 and 100,000, and recent academic studies have argued fatalities were even lower.

In Jewish circles, this massacre became known as Gzeyres Takh Vetat, sometimes shortened to Takh Vetat (spelled in multiple ways in English. In Hebrew: גזירת ת"ח ות"ט). This translates to "the (evil) decrees of (years) 408 and 409" referring to the years 5408 and 5409 on the Jewish calendar, which corresponds to the years 1648 and 1649 on the non-Jewish calendar.

Ukrainian population

While the Cossacks and peasants (known as pospolity) were in many cases the perpetrators of massacres of Polish szlachta members and their collaborators, they also suffered the horrendous loss of life resulting from Polish reprisals, Tatar raids, famine, plague and general destruction due to war.

At the initial stages of the uprising, armies of the magnate Jeremi Wiśniowiecki, on their retreat westward inflicted terrible retribution on the civilian population, leaving behind them a trail of burned towns and villages. ISBN: 0-8020-0591-8.</ref> In addition, Khmelnytsky's Tatar allies often continued their raids against the civilian population, in spite of protests from the Cossacks. After the Cossacks' alliance with Tsardom of Russia was enacted, the Tatar raids became unrestrained; coupled with the onset of famine, they led to a virtual depopulation of whole areas of the country.

From Autumn of 1654 to Spring of 1655 during the "Bracław Campaign" Stefan Czarniecki's army with the support of Crimean Tatars murdered 100,000 Ukrainians some sources even put the number as high as 300,000.

See also

- History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1648)#Cossacks and Cossack rebellions

- Ogniem i Mieczem

- Wars of national liberation

- Russo-Polish War (1654–1667)

- Deluge (history)

- With Fire and Sword (film)

- Pereiaslav Agreement