Katz v. United States facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Katz v. United States |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Argued October 17, 1967 Decided December 18, 1967 |

|

| Full case name | Charles Katz v. United States |

| Citations | 389 U.S. 347 (more)

88 S. Ct. 507; 19 L. Ed. 2d 576; 1967 U.S. LEXIS 2

|

| Prior history | 369 F.2d 130 (9th Cir. 1966); cert. granted, 386 U.S. 954 (1967). |

| Holding | |

| The Fourth Amendment's protection from unreasonable search and seizure extends to any area where a person has a "reasonable expectation of privacy." | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Stewart, joined by Warren, Douglas, Harlan, Brennan, White, Fortas |

| Concurrence | Douglas, joined by Brennan |

| Concurrence | Harlan |

| Concurrence | White |

| Dissent | Black |

| Marshall took no part in the consideration or decision of the case. | |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. IV | |

|

This case overturned a previous ruling or rulings

|

|

| Olmstead v. United States (1928) | |

Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court redefined what constitutes a "search" or "seizure" with regard to the protections of the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. As later decisions have interpreted it, the decision expanded the Fourth Amendment's protections from an individual's "persons, houses, papers, and effects", as specified in the U.S. Constitution, to include any areas where a person has a "reasonable expectation of privacy". The "reasonable expectation of privacy" standard, known as the Katz test, was described by the concurring opinion of justice John Marshall Harlan II. The Katz test has been used in thousands of cases, particularly because of technological advances that create new questions about cultural privacy norms.

Contents

Background

Charles Katz was a sports bettor who by the mid-1960s had become "probably the preeminent college basketball handicapper in America." In February 1965, Katz was using a public telephone booth near his apartment on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, California, to communicate his gambling handicaps to bookmakers in Boston and Miami. Unbeknownst to Katz, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) had begun investigating his gambling activities and was recording his conversations via a covert listening device attached to the outside of the phone booth. After recording many of his phone calls, FBI agents arrested Katz and charged him with eight counts of knowingly transmitting wagering information over telephone between U.S. states, which is a federal crime under 18 U.S.C. § 1084.

Katz was tried in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California. Katz's lawyer made a motion to have the court suppress the FBI's recordings as evidence, arguing that because the FBI agents did not have a search warrant allowing them to place their listening device, the recordings had been made in violation of the Fourth Amendment and should be inadmissible per the exclusionary rule. The judge denied his motion and ruled that the recordings were admissible, and Katz was convicted based on them.

Katz appealed his conviction to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. In November 1966, a three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit affirmed Katz's conviction, ruling that because the FBI's eavesdropping device did not physically penetrate the telephone booth's wall, no Fourth Amendment search occurred, and so the FBI did not need a search warrant to place the device. Katz then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which agreed to hear his case and ordered certiorari. The Supreme Court heard oral arguments on the case in October 1967, and took the unusual step of giving each party a full hour to argue their side.

Decision

On December 18, 1967, the Supreme Court issued a 7–1 decision in favor of Katz that invalidated the FBI's wiretap and overturned Katz's conviction.

Opinion of the Court

Seven justices formed the majority and joined an opinion written by Justice Potter Stewart. The Court began by dismissing the parties' characterization of the case in terms of traditional trespass-based analysis that hinged on, first, whether the public telephone booth Katz had used was a "constitutionally protected area" where he had a "right of privacy", and second, on whether the FBI had "physically penetrated" the protected area and thus violated the Fourth Amendment. Instead, the Court viewed the situation through the lens of how Katz's use of the phone booth would be perceived by himself and then objectively by others. In a now well-known passage, Stewart wrote:

The petitioner [Katz] has strenuously argued that the booth was a "constitutionally protected area." The Government has maintained with equal vigor that it was not. But this effort to decide whether or not a given "area," viewed in the abstract, is "constitutionally protected" deflects attention from the problem presented by this case. For the Fourth Amendment protects people, not places. What a person knowingly exposes to the public, even in his own home or office, is not a subject of Fourth Amendment protection. But what he seeks to preserve as private, even in an area accessible to the public, may be constitutionally protected.

The Court then briefly surveyed the history of American jurisprudence on governmental searches and seizures. It described how American courts had traditionally analyzed Fourth Amendment searches by analogizing them to the long-established doctrine of trespass. In their legal briefs, the parties had focused on the 1928 case Olmstead v. United States, in which the Court had ruled that surveillance by wiretap without any trespass did not constitute a search for Fourth Amendment purposes. However, the Court stated that in later cases it had begun recognizing that the Fourth Amendment governed even recorded speech obtained without any physical trespassing, and that the law had evolved. The Court wrote:

We conclude that the underpinnings of Olmstead [and similar cases] have been so eroded by our subsequent decisions that the "trespass" doctrine there enunciated can no longer be regarded as controlling. The Government's activities in electronically listening to and recording the petitioner's words violated the privacy on which he justifiably relied while using the telephone booth and thus constituted a "search and seizure" within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.

Stewart then concluded the Court's opinion by ruling that even though the FBI knew there was a "strong probability" that Katz was breaking the law with the phone booth, their wiretap was an unconstitutional search because they did not obtain a search warrant before placing it.

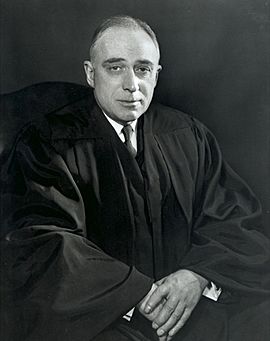

Harlan's concurrence

Justice John Marshall Harlan II's concurring opinion in Katz has become even more well-known than the majority opinion. It describes a two-part test which has come to be known as the "Katz Test".

Harlan began his opinion by noting that he concurred with the majority's judgment, but then explained that he was writing separately to elaborate on the meaning of Stewart's majority opinion. Harlan explained that he interpreted Stewart's statements that "the Fourth Amendment protects people, not places" and "what a person knowingly exposes to the public ... is not a subject of Fourth Amendment protection" to mean that the Fourth Amendment protects any time a person has an expectation of privacy that is both subjective and objectively reasonable in the eyes of society at large. He summarized his view of the law as comprising a two-part test:

My understanding of the rule that has emerged from prior decisions is that there is a twofold requirement, first that a person have exhibited an actual (subjective) expectation of privacy and, second, that the expectation be one that society is prepared to recognize as "reasonable." Thus a man's home is, for most purposes, a place where he expects privacy, but objects, activities, or statements that he exposes to the "plain view" of outsiders are not "protected" because no intention to keep them to himself has been exhibited. On the other hand, conversations in the open would not be protected against being overheard, for the expectation of privacy under the circumstances would be unreasonable.

The Supreme Court eventually adopted Harlan's two-part test as a formulation of the Fourth Amendment search analysis in the 1979 case Smith v. Maryland.

Black's dissent

Justice Hugo Black was the only dissenter in the decision. He argued that the Fourth Amendment was only meant to protect "things" from physical search and seizure, and was not meant to protect personal privacy. Additionally, Black argued that the modern act of wiretapping was analogous to the act of eavesdropping, which was around even when the Bill of Rights was drafted. Black concluded that if the drafters of the Fourth Amendment had meant for it to protect against eavesdropping they would have included the proper language.

Effect and legacy

The Supreme Court's decision in Katz significantly expanded the scope of the Fourth Amendment's protections, and represented an unprecedented shift in American search and seizure jurisprudence. Many law enforcement practices that previously were not "within the view" of the Fourth Amendment—such as wiretaps on public phone wires—are now covered by it and cannot be done without first obtaining a search warrant.

However, Katz also created significantly more uncertainty surrounding the application of the Fourth Amendment. The Katz test of an objective "reasonable expectation of privacy", which has been widely adopted by U.S. courts, has proven much more difficult to apply than the traditional analysis of whether a physical intrusion into "persons, houses, papers, and effects" occurred. In a 2007 Stanford Law Review article, the American legal scholar Orin Kerr summarized:

According to the Supreme Court, the Fourth Amendment regulates government conduct that violates an individual's reasonable expectation of privacy. But no one seems to know what makes an expectation of privacy constitutionally "reasonable." The Supreme Court has repeatedly refused to offer a single test. ... Although four decades have passed since Justice Harlan introduced the test in his concurrence in Katz v. United States, the meaning of the phrase "reasonable expectation of privacy" remains remarkably opaque.

Among scholars, this state of affairs is widely considered an embarrassment. ... Treatises and casebooks struggle to explain the test. Most simply announce the outcomes in the Supreme Court's cases, and some suggest that the only way to identify when an expectation of privacy is reasonable is when five Justices say so. The consensus among scholars is that the Supreme Court's "reasonable expectation of privacy" cases are a failure.