Joseph Conrad facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Joseph Conrad

|

|

|---|---|

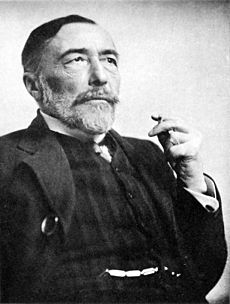

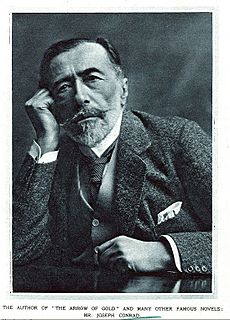

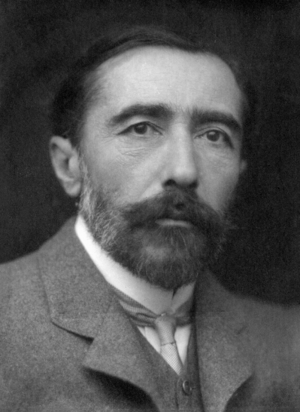

Conrad in 1904 by George Charles Beresford

|

|

| Born | Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski 3 December 1857 Berdychiv, Russian Empire |

| Died | 3 August 1924 (aged 66) Bishopsbourne, Kent, England |

| Resting place | Canterbury Cemetery, Canterbury |

| Occupation | Novelist, short-story writer, essayist |

| Nationality | Polish–British |

| Period | 1895–1923 |

| Genre | Fiction |

| Literary movement |

|

| Spouse |

Jessie George

(m. 1896) |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

|

|

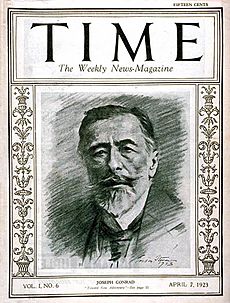

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the English language; though he did not speak English fluently until his twenties. He wrote novels and stories, many in nautical settings, that depict crises of human individuality in the midst of what he saw as an indifferent, inscrutable and amoral world.

Many dramatic films have been adapted from and inspired by his works. Numerous writers and critics have commented that his fictional works, written largely in the first two decades of the 20th century, seem to have anticipated later world events.

Writing near the peak of the British Empire, Conrad drew on the national experiences of his native Poland—during nearly all his life, parceled out among three occupying empires—and on his own experiences in the French and British merchant navies, to create short stories and novels that reflect aspects of a European-dominated world—including imperialism and colonialism.

Contents

Early years

Conrad was born on 3 December 1857 in Berdychiv (Polish: Berdyczów), Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire. He was the only child of Apollo Korzeniowski—a writer, translator, political activist, and would-be revolutionary—and his wife Ewa Bobrowska.

Because of the father's attempts at farming and his political activism, the family moved repeatedly. In May 1861 they moved to Warsaw, where Apollo joined the resistance against the Russian Empire. He was arrested and imprisoned in Pavilion X of the Warsaw Citadel. On 9 May 1862 Apollo and his family were exiled to Vologda, 500 kilometres (310 mi) north of Moscow and known for its bad climate. In January 1863 Apollo's sentence was commuted, and the family was sent to Chernihiv in northeast Ukraine, where conditions were much better. However, on 18 April 1865 Ewa died of tuberculosis.

Apollo did his best to teach Conrad at home. The boy's early reading introduced him to the two elements that later dominated his life: in Victor Hugo's Toilers of the Sea, he encountered the sphere of activity to which he would devote his youth; Shakespeare brought him into the orbit of English literature. Most of all, though, he read Polish Romantic poetry.

On 23 May 1869, Apollo Korzeniowski died, leaving Conrad orphaned at the age of eleven. Like Conrad's mother, Apollo had been gravely ill with tuberculosis.

The young Conrad was placed in the care of Ewa's brother, Tadeusz Bobrowski. Conrad's poor health and his unsatisfactory schoolwork caused his uncle constant problems and no end of financial outlay. Conrad was not a good student; despite tutoring, he excelled only in geography. At that time he likely received private tutoring only, as there is no evidence he attended any school regularly. In the autumn of 1871, thirteen-year-old Conrad announced his intention to become a sailor.

On 13 October 1874 Bobrowski sent the sixteen-year-old to Marseilles, France, for Conrad's planned merchant-marine career on French merchant ships. His uncle provided him with a monthly stipend as well (set at 150 francs). Though Conrad had not completed secondary school, his accomplishments included fluency in French (with a correct accent), some knowledge of Latin, German and Greek; probably a good knowledge of history, some geography, and probably already an interest in physics. He was well read, particularly in Polish Romantic literature. He belonged to the second generation in his family that had had to earn a living outside the family estates.

Merchant marine

After nearly four years in France and on French ships, Conrad joined the British merchant marine, enlisting in April 1878 (he had most likely started learning English shortly before).

For the next fifteen years, he served under the Red Ensign. He worked on a variety of ships as crew member (steward, apprentice, able seaman) and then as third, second and first mate, until eventually achieving captain's rank. During the 19 years from the time that Conrad had left Kraków, in October 1874, until he signed off the Adowa, in January 1894, he had worked in ships, including long periods in port, for 10 years and almost 8 months. He had spent just over 8 years at sea—9 months of it as a passenger. His sole captaincy took place in 1888–89, when he commanded the barque Otago from Sydney to Mauritius.

The year 1890 marked Conrad's first return to Poland, where he would visit his uncle and other relatives and acquaintances. This visit took place while he was waiting to proceed to the Congo Free State, having been hired by Albert Thys, deputy director of the Société Anonyme Belge pour le Commerce du Haut-Congo. Conrad's association with the Belgian company, on the Congo River, would inspire his novella, Heart of Darkness.

Conrad completed his last long-distance voyage as a seaman on 26 July 1893.

Writer

In 1894, aged 36, Conrad reluctantly gave up the sea, partly because of poor health, partly due to unavailability of ships, and partly because he had become so fascinated with writing that he had decided on a literary career. Almayer's Folly, set on the east coast of Borneo, was published in 1895. Its appearance marked his first use of the pen name "Joseph Conrad".

Almayer's Folly, together with its successor, An Outcast of the Islands (1896), laid the foundation for Conrad's reputation as a romantic teller of exotic tales.

Almost all of Conrad's writings were first published in newspapers and magazines. He also wrote for The Outlook, an imperialist weekly magazine, between 1898 and 1906.

Financial success long eluded Conrad, who often requested advances from magazine and book publishers, and loans from acquaintances such as John Galsworthy. Eventually a government grant ("civil list pension") of £100 per annum, awarded on 9 August 1910, somewhat relieved his financial worries, and in time collectors began purchasing his manuscripts. Though his talent was early on recognised by English intellectuals, popular success eluded him until the 1913 publication of Chance, which is often considered one of his weaker novels.

Personal life

Conrad suffered throughout life from ill health, physical and mental. In 1891 he was hospitalised for several months, suffering from gout, neuralgic pains in his right arm and recurrent attacks of malaria. He also complained of swollen hands "which made writing difficult". Conrad had a phobia of dentistry, neglecting his teeth until they had to be extracted. In one letter he remarked that every novel he had written had cost him a tooth.

Marriage

On 24 March 1896 Conrad married an Englishwoman, Jessie George. The couple had two sons, Borys and John.

The couple rented a long series of successive homes, mostly in the English countryside.

Except for several vacations in France and Italy, a 1914 vacation in his native Poland, and a 1923 visit to the United States, Conrad lived the rest of his life in England.

Death

On 3 August 1924, Conrad died at his house, Oswalds, in Bishopsbourne, Kent, England, probably of a heart attack. He was interred at Canterbury Cemetery, Canterbury, under a misspelled version of his original Polish name, as "Joseph Teador Conrad Korzeniowski". Inscribed on his gravestone are the lines from Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene which he had chosen as the epigraph to his last complete novel, The Rover:

Sleep after toyle, port after stormie seas,

Ease after warre, death after life, doth greatly please

Conrad's wife Jessie died twelve years later, on 6 December 1936, and was interred with him.

In 1996 his grave was designated a Grade II listed structure.

Writing style

Themes and style

Conrad wrote oftener about life at sea and in exotic parts than about life on British land because he knew little about everyday domestic relations in Britain.

Conrad used his own memories as literary material so often that readers are tempted to treat his life and work as a single whole. His "view of the world", or elements of it, is often described by citing at once both his private and public statements, passages from his letters, and citations from his books.

Many of Conrad's characters were inspired by actual persons he had met.

Apart from Conrad's own experiences, a number of episodes in his fiction were suggested by past or contemporary publicly known events or literary works. The first half of the 1900 novel Lord Jim (the Patna episode) was inspired by the real-life 1880 story of the SS Jeddah; the second part, to some extent by the life of James Brooke, the first White Rajah of Sarawak.

In Nostromo (completed 1904), the theft of a massive consignment of silver was suggested to Conrad by a story he had heard in the Gulf of Mexico and later read about in a "volume picked up outside a second-hand bookshop."

For the natural surroundings of the high seas, the Malay Archipelago and South America, which Conrad described so vividly, he could rely on his own observations.

Language

Conrad spoke his native Polish and the French language fluently from childhood and only acquired English in his twenties. He would probably have spoken some Ukrainian as a child; he certainly had to have some knowledge of German and Russian.

Conrad chose, however, to write his fiction in English. He says in his preface to A Personal Record that writing in English was for him "natural".

In the opinion of some biographers, Conrad's third language, English, remained under the influence of his first two languages—Polish and French. This makes his English seem unusual.

Citizenship

Conrad was a Russian subject, having been born in the Russian part of what had once been the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. After his father's death, Conrad's uncle Bobrowski had attempted to secure Austrian citizenship for him—to no avail, probably because Conrad had not received permission from Russian authorities to remain abroad permanently and had not been released from being a Russian subject. Conrad could not return to Ukraine, in the Russian Empire—he would have been liable to many years' military service and, as the son of political exiles, to harassment.

In a letter of 9 August 1877, Conrad's uncle Bobrowski broached two important subjects: the desirability of Conrad's naturalisation abroad (tantamount to release from being a Russian subject) and Conrad's plans to join the British merchant marine. "[D]o you speak English?... I never wished you to become naturalized in France, mainly because of the compulsory military service... I thought, however, of your getting naturalized in Switzerland..." In his next letter, Bobrowski supported Conrad's idea of seeking citizenship of the United States or of "one of the more important Southern [American] Republics".

Eventually Conrad would make his home in England. On 2 July 1886 he applied for British nationality, which was granted on 19 August 1886. Yet, in spite of having become a subject of Queen Victoria, Conrad had not ceased to be a subject of Tsar Alexander III. To achieve his freedom from that subjection, he had to make many visits to the Russian Embassy in London and politely reiterate his request. He would later recall the Embassy's home at Belgrave Square in his novel The Secret Agent. Finally, on 2 April 1889, the Russian Ministry of Home Affairs released "the son of a Polish man of letters, captain of the British merchant marine" from the status of Russian subject.

Memorials

An anchor-shaped monument to Conrad at Gdynia, on Poland's Baltic Seacoast, features a quotation from him in Polish: "Nic tak nie nęci, nie rozczarowuje i nie zniewala, jak życie na morzu" ("[T]here is nothing more enticing, disenchanting, and enslaving than the life at sea" – Lord Jim, chapter 2, paragraph 1).

In Circular Quay, Sydney, Australia, a plaque in a "writers walk" commemorates Conrad's visits to Australia between 1879 and 1892. The plaque notes that "Many of his works reflect his 'affection for that young continent.'"

In San Francisco in 1979, a small triangular square at Columbus Avenue and Beach Street, near Fisherman's Wharf, was dedicated as "Joseph Conrad Square" after Conrad. The square's dedication was timed to coincide with release of Francis Ford Coppola's Heart of Darkness-inspired film, Apocalypse Now. Conrad does not appear to have ever visited San Francisco.

In the latter part of World War II, the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Danae was rechristened ORP Conrad and served as part of the Polish Navy.

Notwithstanding the undoubted sufferings that Conrad endured on many of his voyages, sentimentality and canny marketing place him at the best lodgings in several of his destinations. Hotels across the Far East still lay claim to him as an honoured guest, with, however, no evidence to back their claims: Singapore's Raffles Hotel continues to claim he stayed there though he lodged, in fact, at the Sailors' Home nearby. His visit to Bangkok also remains in that city's collective memory, and is recorded in the official history of The Oriental Hotel (where he never, in fact, stayed, lodging aboard his ship, the Otago) along with that of a less well-behaved guest, Somerset Maugham, who pilloried the hotel in a short story in revenge for attempts to eject him.

A plaque commemorating "Joseph Conrad–Korzeniowski" has been installed near Singapore's Fullerton Hotel.

Conrad is also reported to have stayed at Hong Kong's Peninsula Hotel—at a port that, in fact, he never visited. Later literary admirers, notably Graham Greene, followed closely in his footsteps, sometimes requesting the same room and perpetuating myths that have no basis in fact. No Caribbean resort is yet known to have claimed Conrad's patronage, although he is believed to have stayed at a Fort-de-France pension upon arrival in Martinique on his first voyage, in 1875, when he travelled as a passenger on the Mont Blanc.

In April 2013, a monument to Conrad was unveiled in the Russian town of Vologda, where he and his parents lived in exile in 1862–63. The monument was removed, with unclear explanation, in June 2016.

Legacy

After the publication of Chance in 1913, Conrad was the subject of more discussion and praise than any other English writer of the time. He had a genius for companionship, and his circle of friends, which he had begun assembling even prior to his first publications, included authors and other leading lights in the arts, such as Henry James, Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham, John Galsworthy, Galsworthy's wife Ada Galsworthy (translator of French literature), Edward Garnett, Garnett's wife Constance Garnett (translator of Russian literature), Stephen Crane, Hugh Walpole, George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells (whom Conrad dubbed "the historian of the ages to come"), Arnold Bennett, Norman Douglas, Jacob Epstein, T. E. Lawrence, André Gide, Paul Valéry, Maurice Ravel, Valery Larbaud, Saint-John Perse, Edith Wharton, James Huneker, anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski, Józef Retinger (later a founder of the European Movement, which led to the European Union, and author of Conrad and His Contemporaries). In the early 1900s Conrad composed a short series of novels in collaboration with Ford Madox Ford.

In 1919 and 1922 Conrad's growing renown and prestige among writers and critics in continental Europe fostered his hopes for a Nobel Prize in Literature. It was apparently the French and Swedes—not the English—who favoured Conrad's candidacy.

In April 1924 Conrad, who possessed a hereditary Polish status of nobility and coat-of-arms (Nałęcz), declined a (non-hereditary) British knighthood offered by Labour Party Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald. Conrad kept a distance from official structures—he never voted in British national elections—and seems to have been averse to public honours generally; he had already refused honorary degrees from Cambridge, Durham, Edinburgh, Liverpool, and Yale universities.

In the Polish People's Republic, translations of Conrad's works were openly published, except for Under Western Eyes, which in the 1980s was published as an underground "bibuła".

Conrad's narrative style and anti-heroic characters have influenced many authors, including T. S. Eliot, Maria Dąbrowska, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, Gerald Basil Edwards, Ernest Hemingway, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, André Malraux, George Orwell, Graham Greene, William Golding, William Burroughs, Saul Bellow, Gabriel García Márquez, Peter Matthiessen, John le Carré, V. S. Naipaul, Philip Roth, Joan Didion, Thomas Pynchon J. M. Coetzee, and Salman Rushdie. Many films have been adapted from, or inspired by, Conrad's works.

Works

Novels

- Almayer's Folly (1895)

- An Outcast of the Islands (1896)

- The ... of the 'Narcissus' (1897)

- Heart of Darkness (1899)

- Lord Jim (1900)

- The Inheritors (with Ford Madox Ford) (1901)

- Typhoon (1902, begun 1899)

- The End of the Tether (written in 1902; collected in Youth, a Narrative and Two Other Stories, 1902)

- Romance (with Ford Madox Ford, 1903)

- Nostromo (1904)

- The Secret Agent (1907)

- Under Western Eyes (1911)

- Chance (1913)

- Victory (1915)

- The Shadow Line (1917)

- The Arrow of Gold (1919)

- The Rescue (1920)

- The Nature of a Crime (1923, with Ford Madox Ford)

- The Rover (1923)

- Suspense (1925; unfinished, published posthumously)

Stories

- "The Black Mate": written, according to Conrad, in 1886; may be counted as his opus double zero; published 1908; posthumously collected in Tales of Hearsay, 1925.

- "The Idiots": Conrad's truly first short story, which may be counted as his opus zero, was written during his honeymoon (1896), published in The Savoy periodical, 1896, and collected in Tales of Unrest, 1898.

- "The Lagoon": composed 1896; published in Cornhill Magazine, 1897; collected in Tales of Unrest, 1898: "It is the first short story I ever wrote."

- "An Outpost of Progress": written 1896; published in Cosmopolis, 1897, and collected in Tales of Unrest, 1898: "My next [second] effort in short-story writing"; it shows numerous thematic affinities with Heart of Darkness; in 1906, Conrad described it as his "best story".

- "The Return": completed early 1897, while writing "Karain"; never published in magazine form; collected in Tales of Unrest, 1898: "[A]ny kind word about 'The Return' (and there have been such words said at different times) awakens in me the liveliest gratitude, for I know how much the writing of that fantasy has cost me in sheer toil, in temper, and in disillusion." Conrad, who suffered while writing this psychological chef-d'oeuvre of introspection, once remarked: "I hate it."

- "Karain: A Memory": written February–April 1897; published November 1897 in Blackwood's Magazine and collected in Tales of Unrest, 1898: "my third short story in... order of time".

- "Youth": written 1898; collected in Youth, a Narrative, and Two Other Stories, 1902

- "Falk": novella / story, written early 1901; collected only in Typhoon and Other Stories, 1903

- "Amy Foster": composed 1901; published in the Illustrated London News, December 1901, and collected in Typhoon and Other Stories, 1903.

- "To-morrow": written early 1902; serialised in The Pall Mall Magazine, 1902, and collected in Typhoon and Other Stories, 1903

- "Gaspar Ruiz": written after Nostromo in 1904–5; published in The Strand Magazine, 1906, and collected in A Set of Six, 1908 (UK), 1915 (US). This story was the only piece of Conrad's fiction ever adapted by the author for cinema, as Gaspar the Strong Man, 1920.

- "An Anarchist": written late 1905; serialised in Harper's Magazine, 1906; collected in A Set of Six, 1908 (UK), 1915 (US)

- "The Informer": written before January 1906; published, December 1906, in Harper's Magazine, and collected in A Set of Six, 1908 (UK), 1915 (US)

- "The Brute": written early 1906; published in The Daily Chronicle, December 1906; collected in A Set of Six, 1908 (UK), 1915 (US)

- "The Duel: A Military Story": serialised in the UK in The Pall Mall Magazine, early 1908, and later that year in the US as "The Point of Honor", in the periodical Forum; collected in A Set of Six in 1908 and published by Garden City Publishing in 1924. Joseph Fouché makes a cameo appearance.

- "Il Conde" (i.e., "Conte" [The Count]): appeared in Cassell's Magazine (UK), 1908, and Hampton's (US), 1909; collected in A Set of Six, 1908 (UK), 1915 (US)

- "The Secret Sharer": written December 1909; published in Harper's Magazine, 1910, and collected in Twixt Land and Sea, 1912

- "Prince Roman": written 1910, published 1911 in The Oxford and Cambridge Review; posthumously collected in Tales of Hearsay, 1925; based on the story of Prince Roman Sanguszko of Poland (1800–81)

- "A Smile of Fortune": a long story, almost a novella, written in mid-1910; published in London Magazine, February 1911; collected in 'Twixt Land and Sea, 1912

- "Freya of the Seven Isles": a near-novella, written late 1910–early 1911; published in The Metropolitan Magazine and London Magazine, early 1912 and July 1912, respectively; collected in 'Twixt Land and Sea, 1912

- "The Partner": written 1911; published in Within the Tides, 1915

- "The Inn of the Two Witches": written 1913; published in Within the Tides, 1915

- "Because of the Dollars": written 1914; published in Within the Tides, 1915

- "The Planter of Malata": written 1914; published in Within the Tides, 1915

- "The Warrior's Soul": written late 1915–early 1916; published in Land and Water, March 1917; collected in Tales of Hearsay, 1925

- "The Tale": Conrad's only story about World War I; written 1916, first published 1917 in The Strand Magazine; posthumously collected in Tales of Hearsay, 1925

Essays

- "Autocracy and War" (1905)

- The Mirror of the Sea (collection of autobiographical essays first published in various magazines 1904–06), 1906

- A Personal Record (also published as Some Reminiscences), 1912

- The First News, 1918

- The Lesson of the Collision: A monograph upon the loss of the "Empress of Ireland", 1919

- The Polish Question, 1919

- The Shock of War, 1919

- Notes on Life and Letters, 1921

- Notes on My Books, 1921

- Last Essays, edited by Richard Curle, 1926

- The Congo Diary and Other Uncollected Pieces, edited by Zdzisław Najder, 1978, ISBN: 978-0-385-00771-9

Adaptations

A number of works in various genres and media have been based on, or inspired by, Conrad's writings, including:

Cinema

- Victory (1919), directed by Maurice Tourneur

- Gaspar the Strong Man (1920), adapted by Conrad from "Gaspar Ruiz"

- Lord Jim (1925), directed by Victor Fleming

- Niebezpieczny raj (Dangerous Paradise, 1930), a Polish adaptation of Victory

- Dangerous Paradise (1930), an adaptation of Victory directed by William Wellman

- Sabotage (1936), adapted from Conrad's The Secret Agent, directed by Alfred Hitchcock

- Under Western Eyes (1936), directed by Marc Allégret

- Victory (1940), featuring Fredric March

- An Outcast of the Islands (1952), directed by Carol Reed and featuring Trevor Howard

- Laughing Anne (1953), based on Conrad's short story "Because of the Dollars" and his play Laughing Anne.

- Lord Jim (1965), directed by Richard Brooks and starring Peter O'Toole

- The Rover (1967), adaptation of the novel The Rover (1923), directed by Terence Young, featuring Anthony Quinn

- La ligne d'ombre (1973), a TV adaptation of The Shadow Line by Georges Franju

- Smuga cienia (The Shadow Line, 1976), a Polish-British adaptation of The Shadow Line, directed by Andrzej Wajda

- The Duellists (1977), an adaptation by Ridley Scott of "The Duel"

- Naufragio (1977), a Mexican adaptation of "To-morrow" directed by Jaime Humberto Hermosillo

- Apocalypse Now (1979), by Francis Ford Coppola, adapted from Heart of Darkness

- Un reietto delle isole (1980), by Giorgio Moser, an Italian adaptation of An Outcast of the Islands, starring Maria Carta

- Victory (1995), adapted by director Mark Peploe from the novel

- The Secret Agent (1996), starring Bob Hoskins, Patricia Arquette and Gérard Depardieu

- Swept from the Sea (1997), an adaptation of "Amy Foster" directed by Beeban Kidron

- Gabrielle (2005) directed by Patrice Chéreau. Adaptation of the short story "The Return", starring Isabelle Huppert and Pascal Greggory.

- Hanyut (2011), a Malaysian adaptation of Almayer's Folly

- Almayer's Folly (2011), directed by Chantal Akerman

- Secret Sharer (2014), inspired by "The Secret Sharer", directed by Peter Fudakowski

- The Young One (2016), an adaptation of the short story "Youth", directed by Julien Samani

- An Outpost of Progress (2016), an adaptation of the short story "An Outpost of Progress", directed by Hugo Vieira da Silva

Television

- Heart of Darkness (1958), a CBS 90-minute loose adaption on the anthology show Playhouse 90, starring Roddy McDowall, Boris Karloff, and Eartha Kitt

- The Secret Agent (1992 TV series) and The Secret Agent (2016 TV series), BBC TV series adapted from the novel The Secret Agent

- Heart of Darkness (1993) a TNT feature-length adaptation, directed by Nicolas Roeg, starring John Malkovich and Tim Roth; also released on VHS and DVD

- Nostromo (1997), a BBC TV adaptation, co-produced with Italian and Spanish TV networks and WGBH Boston

Operas

- Heart of Darkness (2011), a chamber opera in one act by Tarik O'Regan, with an English-language libretto by artist Tom Phillips.

Orchestral works

- Suite from Heart of Darkness (2013) for orchestra and narrator by Tarik O'Regan, extrapolated from the 2011 opera of the same name.

Video games

- Spec Ops: The Line (2012) by Yager Development, inspired by Heart of Darkness.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Joseph Conrad para niños

In Spanish: Joseph Conrad para niños