José Luis Zamanillo González-Camino facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

José Luis Zamanillo González-Camino

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

José Luis Zamanillo González-Camino

1903 Santander, Spain

|

| Died | 1980 (aged 76–77) Madrid, Spain

|

| Occupation | Lawyer, politician |

| Known for | Politician |

| Political party | CT, FET, UNE |

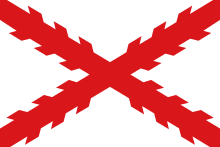

José Luis Zamanillo González-Camino (1903–1980) was a Spanish Traditionalist politician. He was the leader of Carlist paramilitary Requeté structures during the Republic and a champion of Carlist collaborationist policy during mid-Francoism, though in the 1940s he maintained a firm anti-regime stand. He was also a representative of the post-Francoist hard core in the course of early transition to parliamentary democracy. He served in the parliament in two strings of 1933-1936 and 1961–1976; in 1961-1976 he was also a member of the Francoist Consejo Nacional. In 1972-1976 he was a member of Consejo de Estado.

Contents

- Family and youth

- Cortes deputy and paramilitary leader (1931-1936)

- Conspirator and insurgent (1936)

- Dissenting Nationalist (1937-1939)

- Carlist against Francoism (1940-1954)

- Carlist in collaboration (1955-1962)

- Breakup (1962-1963)

- Francoist (1964-1974)

- Post-Francoist Traditionalist (1975-1980)

- See also

Family and youth

José Luis' paternal ancestors originated from Biscay; the great-grandfather was a pharmacist. His son Gregorio Zamanillo del Campo also ran a pharmacy, first in the Biscay Carrantza and later in the Cantabrian Laredo. Politically he sympathized with Carlism, though after the 1888 Integrist breakup he followed the secessionists. Gregorio was married twice; José Luis' father, José Zamanillo Monreal (1866-1920), was born out of the second marriage. He also became a pharmacist and owned a business in Santander; like his predecessor, he also developed Integrist sympathies. At the turn of the centuries he emerged as a recognized local Traditionalist activist; he co-organized Centro Católico Montañés, the Integrist outpost in Cantabria, co-founded urban and rural Catholic trade unions, and became president of La Propaganda Católica de Santander, a publishing house issuing El Diario Montañés, a militantly anti-liberal daily affiliated with the Santander bishopry. President of the Integrist Junta Provincial and member of the regional Castilla La Vieja executive, in 1909-11 he served as concejal in the Santander ayuntamiento and in 1915 briefly as diputado provincial.

Zamanillo Monreal married María González-Camino y Velasco, descendant to a bourgeoisie family originating from Esles de Cayón. It was founded by an enriched indiano, Francisco González-Camino, and has traditionally remained in the first row of business, politics and culture in the region, holding stakes in companies from banking, insurance, industry, railways, electrify, utilities and other businesses. José and María settled in Santander and had 6 children; they were brought up "en un hogar español cristiano y montañes", learning "to prey to God and to love Spain" and with a sense of local Cantabrian pride. José Luis was born as the second oldest son. His older brother Nicolás followed in the footsteps of 3 generations and also became a pharmacist, his younger brother Gregorio became a physician. Two of his sisters tried their hand in letters, Matilde more successful than María; all were active in Traditionalism.

Little is known about education of José Luis; at one point he left family home to join the Jesuit college of the Biscay Orduña, where he obtained bachillerato. Then he commenced law studies and one source claims he graduated at Deusto; date of his graduation is not known, normally it would have fallen on the mid-1920s. He commenced law career in his native Santander; details are not clear, except that in 1930 he already practiced on his own handling civil cases and in 1931 was referred to as "joven abogado". In 1931 José Luis married Luisa Urquiza y Castillo (1905-2002); none of the sources consulted provides any information on her family. The couple settled in Santander and had 12 children; 2 of them died in infancy. None of them grew to prominence, though some were active Traditionalists. The best-known relative of José Luis is his older cousin, Marcial Solana González-Camino; an Integrist Cortes deputy in 1916, he made his name in the 1920s and 1930s as Traditionalist philosopher and author.

Cortes deputy and paramilitary leader (1931-1936)

José Luis engaged in unspecified Integrist activity already during last years of the monarchy. When in late 1931 the party commenced re-integration into Carlism, the three Zamanillo brothers followed suit and joined the united Comunión Tradicionalista. It seems that José Luis remained in the shadow of Nicolás, who led Juventud Integrista, was noted as public speaker in 1932 and grew to head of Juventud Tradicionalista in Santander. During the run-up to the 1933 elections it seemed that Nicolás would emerge at the forefront, but in unclear circumstances it turned out that José Luis represented the Carlists on the joint Santander list of Unión de Derechas Agrarias. He was comfortably elected and somewhat unexpectedly he emerged among 20-odd Carlist deputies, most distinguished figures of the Comunión, and one of the few representing a new generation. Zamanillo's rise was so startling that to acknowledge it, editors celebrating 100 years of Carlism had to hastily amend their publications.

Zamanillo remained moderately active as a deputy. He joined Comisión de Comunicaciones and formed a group advancing the interests of Cantabrian fishermen, later growing to head of its Junta Directiva. During general sessions he was noted as following the overall Carlist strategy, highly suspicious towards the CEDA-Radical governments, at times taking part in parliamentary obstruction and rather occasionally making it to the headlines of the Carlist press. It was not Cortes activity which gained him recognition in the party. Following a general overhaul of Comunión command layer in 1934 the former Integrists gained a strong position and their man Manuel Fal Conde rose to Jéfe Delegado. It was Fal who in May 1934 appointed Zamanillo head of Special Delegation for the Requeté, section of the party executive co-ordinating growth of the Carlist paramilitary. With neither military training nor combat experience, Zamanillo was entrusted with general organization, financing, logistics, recruitment, personal policy and overall guidance. His key objective was to re-format requeté into a nationwide Frente Nacional de Boinas Rojas, the task successfully carried out in course of 1935. Himself involved in logistics, he was however focused on recruitment, with the overall Requeté strength growing from 4,000 in late 1934 to 25,000 in mid-1936.

Politically Zamanillo remained among the Carlist hawks; though he signed the Bloque Nacional funding act, in 1935 he developed enmity towards the monarchist alliance advanced by the likes of Rodezno and Pradera. On the other hand, he remained on excellent terms with the Cantabrian Falange and its leader Manuel Hedilla. The policy backfired when in 1936 the Carlists were left out of the local Cantabrian Candidatura Contrarrevolucionaria; standing on their own they fared badly and Zamanillo lost his Cortes ticket with just 12,000 votes gathered. He could have focused on buildup of requete structures, considered its "protagonista fundamental"; he was touring the country, delivering addresses, attending meetings and mobilizing support. At that time initially defensive Requeté format was rapidly being re-defined to embrace a new, insurgent strategy.

Conspirator and insurgent (1936)

In March 1936 Zamanillo entered a Carlist body co-ordinating preparations to a rising and based in Sant-Jean-de-Luz. He was among key architects of a so-called "Plan de los Tres Frentes", a project of toppling the Republic by means of an exclusively Carlist coup; it crashed in early June when security unearthed a depot with hundreds of false Guardia Civil uniforms. Preparations were re-formatted as negotiations with the military conspiracy. Since 1935 engaged in noncommittal talks with UME he took part in key debates of early summer, meeting general Mola on June 11 and July 2. In conspiracy using the alias of "Sanjuan", Zamanillo was cruising between Sant-Jean-de-Luz, his temporary headquarters of Elizondo, Irun and Estella. He adhered to the line advocated by Fal, who demanded that political deal is concluded first and who opposed unconditional access to military coup. Details are not entirely clear; at one point it seemed that negotiations with increasingly desperate Mola have crashed, but eventually the Navarrese outmaneuvered Fal and closed an ambiguous deal. On July 15 Zamanillo ordered requeté mobilization and 2 days later he issued the order to rise.

As the hostilities broke out Zamanillo was flown together with Fal from southern France to the Nationalist zone. In August 1936 he entered Junta Nacional Carlista de Guerra, the new wartime executive Carlist structure; he co-headed Delegación Nacional de Requeté, a sub-unit of Sección Militar, with his duties related to recruitment, personal appointments and general administration. In September he toured the frontlines, hailing common Carlist-Falangist comradeship, lambasting CEDA and somewhat belittling the military. Congratulated by his king Alfonso Carlos, following his death in October he travelled to Vienna to attend the funeral. Having hardly noticed the ascent of Franco he rather saluted Don Javier as a new caudillo and had problems coming to terms with the vision of perhaps necessary, transitional military dictatorship before a Traditionalist monarchy gets reinstated.

In late 1936 Zamanillo kept co-ordinating requeté recruitment and organization, voicing strongly in favor of independence and regional basis of the Carlist units. Informal talks with the military produced an idea of organizing systematic training for Carlist would-be officers, the concept which materialized as Real Academia Militar de Requetés, announced by Fal to be set up shortly. As it was initially to be based in Pamplona, Zamanillo contacted the Navarrese Carlists in an apparent bid to offer an olive branch and address increasingly sour relations between their Junta Central Carlista de Guerra de Navarra and the Burgos-based Junta Nacional Carlista de Guerra. On December 20 he accompanied Fal in his journey from Toledo to Franco's Salamanca headquarters but was left in antechamber when Dávila presented Fal with an alternative of either exile or the firing squad. Later the same day he took part in an improvised session of Junta Nacional, discussing the ultimatum from the military; Zamanillo's stand is not clear, before later the same day he returned with Fal to Toledo.

Dissenting Nationalist (1937-1939)

While Fal complied with the military ultimatum and left the Nationalist zone for Portugal, within the Carlist command Zamanillo formed the faction of his most staunch supporters. Already in early January 1937 he met Dávila in vain seeking to ensure Fal's return, yet at the time the lot of Jefe Delegado was getting gradually eclipsed by rumors of amalgamating Carlism into sort of a new state party. Zamanillo took part in the February session of Carlist heavyweights in the Portuguese Insua, which confirmed him as member of the strict 7-member executive. During the following session, held in March in Burgos, he and Valiente acted as chief Falcondistas and displayed most skepticism about would-be unification, confirming that attacks against Comunión hierarchy were unacceptable; nevertheless, the junta vaguely and unanimously agreed that political unity was a must. The same month he denounced political maneuvering and presented the military with Don Javier's letter advocating the return of Fal; though Zamanillo remained on amicable terms with Mola, he was viewed increasingly unfavorably in Franco's entourage. In the final meeting of Carlist executive in Burgos of early April 1937 he assumed a hard line, protesting alien intervention in Carlist affairs.

In the aftermath of Unification Decree, on April 19 enraged Zamanillo resigned from all functions; he was so disgusted with apparent bewilderment among the Carlist executive that he concluded that Fal's exile worked to his advantage, allowing Jefe Delegado to maintain an honorable position. A number of sources claim that embittered, Zamanillo enlisted to combat requeté units, though none provides any details of his service. He might have enlisted to Tercio de Navarra or Tercio de Palencia, where his brothers served, though scarce information does not allow to tell which Zamanillo was meant in the reports. In May 1937 he was still noted in Pamplona, when dodging unification process he was issuing antedated requeté promotions. Also later Zamanillo kept sabotaging unification; in November 1937 and still in Pamplona he assisted Carlist volunteers who deserted from Falange-dominated units and re-directed them to newly formed Navarrese tercios.

Once Cantabria had been taken over by the Nationalists some young local Carlists started to form anti-unification resistance groups. The dissenters, dubbed "Tercio José Luis Zamanillo", were eventually prosecuted; it is not clear to what extent Zamanillo was involved and whether he held any posts in the new Nationalist administration of Santander. There is almost no information on Zamanillo's whereabouts during 1938, except minor pieces related to occasional Carlist feasts. In early 1939, shortly before the end of the war, he co-signed a document named Manifestacion de los Ideales Tradicionalistas, a memorandum of key Carlist politicians; delivered to Franco, it contained a lengthy discourse arguing that once the war was about to end, it was time to introduce the Traditionalist monarchy. The document was left with no response.

Carlist against Francoism (1940-1954)

In the early 1940s, Zamanillo formed the core of Falcondistas, acting as watchdogs of the Carlist orthodoxy. Fal, partially incommunicado, considered him, Senante and Lamamié "el triunvirato de los feroces integristas tachados de intemprantes" and indeed as Fal's trustee he carried out appointments in Navarre, always keen to pursue their own policy. He made sure that Comunión remained neutral towards the European war, that claims of the new Alfonsist claimant Don Juan were rejected with pro-Juanista sympathies eradicated and that there was no political collaboration with the regime. In a 1941 document he castigated Francoism as totalitarian system rejected by the society. Touring the country from Seville to Barcelona Zamanillo delivered addresses at meetings styled as Christian or ex-combatant feasts. In 1943 he co-signed Reclamacion del poder, Carlist memorandum demanding introduction of Traditionalist monarchy; in May he was detained, spent a week in police dungeons and was ordered exile in Albacete, terminated in April 1944. Still head of Requeté structures he tried to prevent their disintegration. In 1945 he was among those behind Pamplona riots; detained and trialed in early 1946, Zamanillo was the only member of Carlist executive sentenced to unconditional incarceration.

By May 1946 Zamanillo was free again, speaking at the predominantly Carlist Montserrat feast. He used to attend the gathering systematically, present also in 1947, though in the late 1940s his relations with Sivatte, chief personality of Catalan Carlism, deteriorated; Zamanillo's calls for discipline were largely aimed against the Sivattistas. Confirmed as member of Consejo Nacional and attending the first gathering or regional leaders since Insua he was bent on preserving Traditionalist identity against Francoist distortions and called for setting up Centro de Estudios Doctrinales. An awkward sign of recognition came in wake of his 1948 trip to Rome, when the émigré PSUC periodical noted him among "dirigents del [Carlist] movimient" whose dissidence demonstrated ongoing decomposition of Francoism.

It is neither clear where Zamanillo lived in the late 1940s and early 1950s nor how he made a living; sporadically he was mentioned as related either to Santander or to Madrid, in both cases connected to the education system. Most likely he kept practicing as a lawyer, as demonstrated by proceedings related both to minors and to politics: in 1953 he was involved in machinations to ensure that former wife of another Carlist claimant, the late Carlos VIII, would not get legal custody of their juvenile daughters. As the action was allegedly triggered by Franco himself, the episode might be indicative of Zamanillo's improving relations with the regime. On the Carlist front he remained loyal to Fal and kept fighting the increasingly vocal Sivattistas; none of the sources consulted clarifies whether he joined those pressing Don Javier to terminate the regency and to claim monarchic rights himself, what sort of happened in Barcelona in 1952; it was only much later that he declared it a grave error. In 1954 he was confirmed as a member of largely inactive Junta Nacional and its day-to-day executive, a Permanent Commission.

Carlist in collaboration (1955-1962)

When Fal Conde resigned in August 1955 Zamanillo was still member of Junta Nacional and one of the party moguls. Don Javier did not nominate a new Jefe Delegado, creating a new collegial executive, Secretaría Nacional; according to some scholars Zamanillo initially was not appointed and got recommended by Fal slightly afterwards, according to others he formed part from the onset. At that time those advocating more intransigence competed with those advocating more flexibility. It is not clear where Zamanillo stood; for 20 years the right hand of adamant Fal, only some time later he emerged as supporter of the collaborative strategy, championed by Valiente. Within Carlism the anti-Francoist feelings were running high, with especially the Navarros and the Gipuzkoanos trying to sabotage his nomination; during the 1956 Montejurra gathering they tried to block his access to the microphone, and when he finally succeeded, they cut the cables. However, the collaborationists and Zamanillo consolidated their position; backed by the claimant, who conferred Carlist honors upon him, he was handling the link to Movimiento, a tricky task as the Carlist rank and file booed and jeered whenever the name of the Francoist state party was mentioned. Together with Valiente and Saenz-Díez he soon emerged as member of a new triumvirate running the party.

The new strategy seemed to work and in 1957 Zamanillo was rumored to land a ministerial job or a high position in Movimiento, the perspective which faded away once Arrese had been replaced with Solis. Undeterred, he kept advocating flexibility towards the regime as the best way to confront Juanistas, who should be beaten not "en los montes sino desde los cargos oficiales". In 1958 he was nominated secretario general, a new position reporting only to Valiente, and the same year got double-hatted as regional jefe of Castilla la Vieja. He cautiously endorsed introduction of the Carlist prince Carlos Hugo and taking advantage of his links with the regime officials intervened to spare him trouble, be it after the 1958 Montejurra, before the 1960 Montejurra, securing his residence permit in Madrid in 1960 and 1961 or launching the bid for Spanish citizenship for the Borbon-Parmas.

At the turn of the decades, Zamanillo's position in Carlism reached its climax. Though Valiente was officially nominated new Jefe Delegado, due to his requeté past Zamanillo enjoyed more prestige; he handed over the post of requeté leader as late as 1960. Within the party he was entrusted with disciplinary missions. When addressing gatherings at Montserrat and Montejurra he could have afforded to ignore suggestions of Movimiento and Carlist leaders alike. During aplecs advocating "religious unity consubstantial with national unity", since 1959 he organized "marchas al Valle de los Caídos", an initiative providing opportunity to fraternize with the Falangists and himself frequently wined and dined with the Movimiento officials, even though he was suspicious about genuine intentions of the regime. In 1961 Zamanillo was nominated to Consejo Nacional, which guaranteed seat in the Cortes, and in 1962 he was admitted by Franco.

Breakup (1962-1963)

Zamanillo's interventions facilitating Carlos Hugo's entry proved successful and in January 1962 the young prince settled in Madrid. He turned a group of his young entourage into Secretaría Privada, which in turn embarked on a number of new initiatives. Zamanillo viewed them as part of the collaborationist strategy and supported; in 1960 Semana Nacional de Estudios of AET in Valle de los Caidós he spoke about a possibilist evolution of the doctrine and engaged in Círculos Vázquez de Mella. The sympathy, however, was not reciprocal. Unlike the older generation, for whom Zamanillo was an icon of requeté, Carlos Hugo and his aides, like Ramón Massó and José María Zavala, were far more skeptical. They considered him an old-type man of the past, valiant but with scarce political intuition and tending to inactivity. Once the Hugocarlistas gained formal outposts and launched own initiatives, friendly but loose early relations were getting thorny. Initially it looked like a generational conflict, not helped by Zamanillo's unshakable sense of own authority. He was getting uneasy about what was becoming known as "camarilla" of the prince, the youth were skeptical about his power-hungry "requeté cohort".

In few weeks suspicion turned into a full-scale conflict, especially that upon closer contact Zamanillo developed doubts about Traditionalist orthodoxy of the Hugocarlistas. They also identified him as a chief obstacle in their path to power and got determined to remove it. Conscious of royal support they did not step back and provoked Zamanillo to resign from his post in the executive; he intended the move as a mere demonstration of protest. With his resignation awaiting royal decision, in the spring of 1962 he opposed structural changes proposed by Hugocarlistas and spoke out against "delfinismo", which puts "sons against fathers". At the same time he launched Hermandad de Antiguos Combatientes de Tercios de Requeté, an organization supposed to help in the imminent clash for power, and openly confronted new advancements of Carlos Hugo. The conflict materialized over few other issues yet did not seem unbridgeable until in September 1962 his resignation – to Zamanillo's shock and amazement and against the advice of Valiente – was accepted.

Since the fall of 1962 Zamanillo developed a furious anti-Hugocarlista activity; it culminated in a letter, denouncing Carlos Hugo as ignorant and subversive revolutionary. In 1963 Massó and his men prepared ground for final confrontation, marginalizing Zamanillo's supporters, floating rumors about his treason and mobilizing support of iconic personalities. Zamanillo played into their hands resigning from further functions, also in Hermandad. The climax came in June 1963, when on a party council the Hugocarlistas launched an all-out attack advancing a number of charges. In November Secretaría demanded that Zamanillo be expulsed; Don Javier had few doubts and Zamanillo was purged by the year-end. Hugocarlista strategy worked perfectly; disguising their progressive agenda they deflected the conflict from ideological confrontation to secondary issues, isolated their opponent, provoked him into unguarded moves, and removed the key person bent on preventing their intended control of Carlism.

Francoist (1964-1974)

In the early 1960s Zamanillo was already considered icon of collaborationism, as evidenced by his 1961 nomination to its Consejo Nacional. In 1962 Franco thought him a candidate for vice-minister of justice, nomination thwarted by Carrero Blanco, who denounced him – either erroneously or as part of own stratagem – as supporter of Carlos Hugo. Following expulsion from Carlism Zamanillo was welcome among the Movimiento hardliners. In 1964 he was awarded Gran Cruz del Mérito Civil, a visible sign of excellent relations with the regime. His nomination to Consejo was renewed in 1964, to be prolonged in 1967 and 1971; as consejero he had seat in the Cortes guaranteed.

Within the Francoist structures Zamanillo entered important though not front-row bodies. In 1964 he became secretary of Comisión de Ordenación Institucional, entrusted with working out a new recipe for Falangism; in 1967 he was secretary to its later incarnation, the section of "Principios fundamentales y desarollo político". In the Cortes he worked in commission drafting Ley Orgánica del Movimiento, an eventually abandoned attempt to ensure Falangist domination. In 1967 he grew to one of 4 secretarios of the diet, the function renewed also in 1971, and represented Spain in international inter-parliamentary bodies. In 1970 Zamanillo's status was acknowledged with Gran Cruz de la Orden del Mérito Militár. In terms of officialdom his position climaxed in 1972, when Zamanillo entered Consejo de Estado.

In terms of impact on real-life politics Zamanillo found himself increasingly marginalized; he sided with the Falangist core, which during the 1960s was outmaneuvered by the technocratic bureaucracy. Though speaking with Franco "many times" and allegedly conceded to be right, he failed to influence the caudillo who allowed political changes that Zamanillo opposed, like liberalization of the labor law or the press law; the project which drew his particular enmity was the 1967 Law on Religious Liberties. On the other hand, he supported the 1966 introduction of Tercio Familiar as a step towards Traditionalist type of representation; claiming that backbone of Traditionalism was doctrinal rather than dynastical in 1969 he voted in favor of Juan Carlos as the future king. In late 1973 Zamanillo participated in one of the last hardline attempts to seize control, Comisión Mixta Gobierno-Consejo Nacional, dissolved soon afterward by Carrero Blanco.

Labeled "falso carlista" by Don Javier, Zamanillo kept considering himself a Carlist. He kept leading Hermandad of ex-combatants, periodically purging it of the most vocal Javieristas; at the turn of the decades he considered it a would-be platform to launch a new Carlist organization, a "Comunión without a king". The organization finally animated to this end was already existing Hermandad de Maestrazgo; Zamanillo presided over its Patronat Nacional in 1972 and in 1973 entered its collegial presidency. With Valiente and Ramón Forcadell considered a triumvirate running the group, he emphasized Falangist and Traditionalist commonality in the service of Spain and Franco. The organization failed to attract popular support and did not become a genuine Carlist counterweight to the newly emergent Partido Carlista.

Post-Francoist Traditionalist (1975-1980)

During the final years of Francoism Zamanillo engaged in the launch of a broad Traditionalist organization. Following the so-called Ley Arias of December 1974, which legalized political associations, he first tried to mobilize support by means of a new periodical, Brújula, gathering together "partidarios de la Monarquía tradicional, social y representativa". In June 1975 the initiative materialized with 25,000 signatures required as Unión Nacional Española; Zamanillo entered its Comisión Permanente and in early 1976 jointly with Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora its presidency, becoming also member of Junta Directiva. The association, in 1976 officially registered as political party, adhered to Traditionalist principles; Zamanillo explained its objectives as "lo que hay que hacer es un 18 de julio pacífico y político", played down differences with other right-wing groupings and advanced suggestions of a National Front, formed by UNE, ANEPA, UDPE and others. In May 1976 he co-organized Traditionalist attempt to dominate the annual Carlist Montejurra gathering, since mid-1960s controlled by the Hugocarlistas; the day produced violence, with two Partido Carlista militants shot.

Still member of the Cortes, when forming factions had been allowed Zamanillo joined Acción Institucional, the closest one to the hardline búnker. .....

In gear-up to the elections in late 1976 UNE joined the Alianza Popular coalition and Zamanillo signed its founding manifesto. In parallel, apparently somewhat skeptical about the UNE format and definitely disillusioned about Juan Carlos, in February 1977 he co-founded a strictly Carlist organization, Comunión Tradicionalista, and entered its executive; dynastic leader of the party turned out to be Sixto, Traditionalist younger brother of Carlos Hugo. In the June 1977 elections Zamanillo ran for the senate on the UNE/AP list from Santander, but suffered heavy defeat. UNE was getting increasingly divided about the general strategy; its November 1977 General Assembly turned into mayhem. Zamanillo and his supporters demanded leaving AP; in the ensuing chaos, they staged a parallel session and elected a new party executive. The opposing faction of Fernández de la Mora appealed in court and won; in December 1977 Zamanillo was expulsed from UNE. He then focused on Comunión, which prior to 1979 elections joined the Unión Nacional alliance; this time Zamanillo did not run.

See also

In Spanish: José Luis Zamanillo para niños

In Spanish: José Luis Zamanillo para niños

- Carlism

- Spanish Civil War

- Carlo-francoism

- Spanish transition to democracy