John Anthony Copeland Jr. facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Anthony Copeland Jr.

|

|

|---|---|

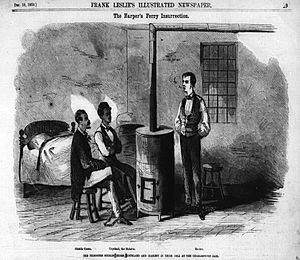

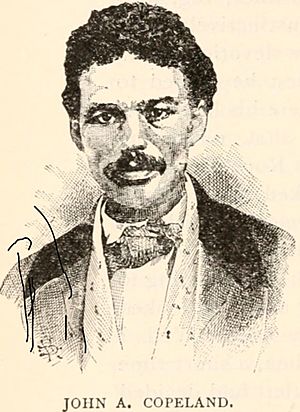

John Copeland in 1859, drawing from a newspaper, likely made during his trial

|

|

| Born | 1834 Raleigh, North Carolina, United States

|

| Died | December 16, 1859 (aged 24–25) |

| Cause of death | Hanging |

| Education | Oberlin Collegiate Institute (preparatory division) |

| Known for | Oberlin-Wellington Rescue Raid on Harpers Ferry |

John Anthony Copeland Jr. (August 15, 1834 – December 16, 1859) was born free in Raleigh, North Carolina, one of the eight children born to John Copeland Sr. and his wife Delilah Evans, free mulattos, who married in Raleigh in 1831. Delilah was born free, while John was manumitted in the will of his master. In 1843 the family moved north, to the abolitionist center of Oberlin, Ohio, where he later attended Oberlin College's preparatory (high school) division. He was a highly visible leader in the successful Oberlin-Wellington Rescue of 1858, for which he was indicted but not tried. Copeland joined John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry; other than Brown himself, he was the only member of John Brown's raiders that was at all well known. He was captured, and a marshal from Ohio came to Charles Town to serve him with the indictment. He was indicted a second time, for murder and conspiracy to incite slaves to rebellion. He was found guilty and was executed on December 16, 1859. There were 1,600 spectators. His family tried but failed to recover his body, which was taken by medical students for dissection, and the bones discarded.

Life

Copeland's parents were John Anthony Copeland, who was born into slavery in 1808, near Raleigh, North Carolina, and Delilah Evans, born a free black in 1809. Copeland Sr. was emancipated as a boy about 1815 by the will of his owner, who was also his father. As a young man, he married Evans and they lived near Hillsborough, North Carolina, until 1843, when the family fled racial persecution, first to Cincinnati, Ohio, and then to Oberlin. Some of his wife's brothers and their families also settled there. The Copelands lived on the southeast corner of Professor and Morgan Streets, but then moved to a small farm just outside the village on West Hamilton St. John Sr. worked as a carpenter and a joiner, and also acted as a Methodist preacher.

The son became a carpenter and briefly attended the preparatory division of Oberlin College. His high quality of literacy and self-expression was demonstrated by later letters to his family (see below). According to Ralph Plumb, he was well-educated. He was also described as "east-going, ingratiating, and assimilated. As a young man, he became involved in the Oberlin Anti-Slavery Society.

In 1859, in reporting on the raid, a Dayton newspaper reported that Copeland "has been long a resident of our goodly city."

Anti-slavery activities

Together with his maternal uncles, Henry and Wilson Bruce Evans, in September, 1858, Copeland was a leader of the thirty-seven men involved in the incident known as the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, freeing John Price, a runaway slave who had been captured and held by authorities under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. The men freed the slave and helped him escape to Canada. Copeland was indicted but escaped arrest, and was himself a fugitive at the time he joined John Brown's team.

In September 1859 Copeland was recruited to participate in John Brown's failed raid on Harpers Ferry by his uncle and fellow raider, Lewis Sheridan Leary. Copeland's role in the Harpers Ferry assault was to seize control of Hall's Rifle Works, along with John Henry Kagi, a white raider. Kagi and several others were killed while trying to escape from the Rifle Works by swimming across the Shenandoah River. Copeland was captured alive, taken in the middle of the river.

Copeland, Brown, and five others were held for trial by the state of Virginia. He was also visited by marshals seeking him for the Wellington rescue indictment. He made a full confession to the marshals.

At the trial, Copeland was found guilty of murder and conspiracy to incite slaves to rebellion, and sentenced to death by hanging. A charge of treason was dropped, as his attorney, George Sennott, citing the Dred Scott decision, successfully argued that since Copeland was not a citizen under that Supreme Court ruling, he could not commit treason.

The barn and stables of Walter Shirley, foreman of the jury that convicted Copeland, were burned on the night of his conviction.

Copeland wrote to his family to make meaning from his sacrifice. Six days before his execution, he wrote to his brother, referring to the American Revolution:

And now, brother, for having lent my aid to a general no less brave [than George Washington], and engaged in a cause no less honorable and glorious, I am to suffer death. Washington entered the field to fight for the freedom of the American people—not for the white man alone, but for both black and white. Nor were they white men alone who fought for the freedom of this country. The blood of black men flowed as freely as the blood of white men. Yes, the very first blood that was spilt was that of a negro... But this you know as well as I do, ...the claims which we, as colored men, have on the American people.

Another letter reflected the religious influence of his Oberlin upbringing. In a December 16 letter, Copeland wrote to console his family:

Why should you sorrow? Why should your hearts be racked with grief? Have I not everything to gain and nothing to lose by the change? I fully believe that not only myself but also all three of my poor comrades who are to ascend the same scaffold (a scaffold already made sacred to the cause of freedom, by the death of that great champion of human freedom, Capt. JOHN BROWN) we are prepared to meet our God.

The family allowed the letters to be published in the abolitionist press.

Speaking of Copeland, the trial's prosecuting attorney, Andrew Hunter, said:

From my intercourse with him I regarded him as one of the most respectable prisoners we had. ...He was a copper-colored Negro, behaved himself with as much firmness as any of them, and with far more dignity. If it had been possible to recommend a pardon for any of them, it would have been for this man Copeland, as I regretted as much, if not more, at seeing him executed than any other one of the party.

Death

Copeland was executed at Charles Town, Virginia, on December 16, 1859. On his way to the gallows he reportedly said, "If I am dying for freedom, I could not die for a better cause. I had rather die than be a slave."

Legacy and honors

- On December 25, 1859, a memorial service was held in Oberlin for Copeland, Green, and Lewis Sheridan Leary, who died during the raid.

- A cenotaph was erected in 1865, after the Civil War, in Westwood Cemetery to honor the three "citizens of Oberlin." The monument was moved in 1977 to Martin Luther King Jr. Park on Vine Street in Oberlin. The inscription reads:

- "These colored citizens of Oberlin, the heroic associates of the immortal John Brown, gave their lives for the slave. Et nunc servitudo etiam mortua est, laus deo. (And now slavery is finally dead, thanks be to God.)

- S. Green died at Charleston, Va., Dec. 16, 1859, age 23 years.

- J. A. Copeland died at Charleston, Va., Dec. 16, 1859, age 25 years.

- L. S. Leary died at Harper's Ferry, Va., Oct 20, 1859, age 24 years."

See also

- John Brown's raiders