Jacobus Arminius facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jacobus Arminius

|

|

|---|---|

| Jakob Hermanszoon | |

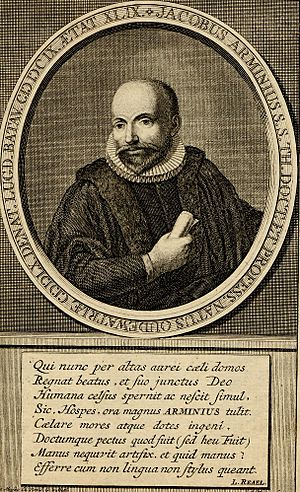

Jacobus Arminius (1620) by David Bailly

|

|

| Born | 10 October 1560 |

| Died | 19 October 1609 (aged 49) |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Education | Leiden University |

| Occupation | Pastor, theologian |

| Spouse(s) | Lijsbet Reael |

| Theological work | |

| Era | Reformation |

| Tradition or movement | Arminianism |

| Main interests | Soteriology |

| Notable ideas | Prevenient grace, conditional preservation of the saints |

Jacobus Arminius (/ɑːrˈmɪniəs/; 10 October 1560 – 19 October 1609), the Latinized name of Jakob Hermanszoon, was a Dutch Reformed minister and theologian during the Protestant Reformation period whose views became the basis of Arminianism and the Dutch Remonstrant movement. He served from 1603 as professor in theology at the University of Leiden and wrote many books and treatises on theology.

Following his death, his challenge to the Reformed standard, the Belgic Confession, provoked ample discussion at the Synod of Dort, which crafted the five points of Calvinism in response to Arminius's teaching.

Contents

Early life

Arminius, was born in 1559 or 1560 in Oudewater, Utrecht. He became an orphan while still young. His father Herman, a manufacturer of weapons, died, leaving his wife a widow with small children. He never knew his father, and his mother was killed during the Spanish massacre at Oudewater in 1575.

The child was adopted by Theodorus Aemilius, a priest inclined towards Protestantism. Around 1572 (the year Oudewater was conquered by the rebels), Arminius and Aemilius settled in Utrecht. The young Jacobus studied there, probably at the Hieronymusschool. After the death of Aemilius (1574 or 1575), Arminius became acquainted with the mathematician Rudolph Snellius, also from Oudewater. The latter brought Arminius to Marburg and enabled him to study at the Leiden University, where he taught. In 1576, Arminius was registered as a liberal arts student at the newly opened Leiden University.

Theological studies and ministry

Arminius remained a student at Leiden from 1576 to 1582. Although he enrolled as a student in Liberal Arts, this allowed him to pursue an education in theology, as well. His teachers in theology included Calvinist Lambertus Danaeus, Hebrew scholar Johannes Drusius, Guillaume Feuguereius (or Feugueires, d. 1613), and Johann Kolmann. Kolmann is now known for teaching that the overemphasis of God's sovereignty in high Calvinism made God "a tyrant and an executioner". Although the university in Leiden was solidly Reformed, it had influences from Lutheran, Zwinglian, and Anabaptist views in addition to Calvinism. One Leiden pastor (Caspar Coolhaes) held, contra Calvin, that civil authorities did have jurisdiction in some church affairs, that it was wrong to punish and execute heretics, and that Lutherans, Calvinists, and Anabaptists could unite around core tenets. The astronomer and mathematician Willebrord Snellius used Ramist philosophy in an effort to encourage his students to pursue truth without over reliance on Aristotle. Under the influence of these men, Arminius studied with success and may have had seeds planted that would begin to develop into a theology that would later question the dominant Reformed theology of John Calvin. The success he showed in his studies motivated the merchants guild of Amsterdam to fund the next three years of his studies.

In 1582, Arminius began studying under Theodore Beza at Geneva. He found himself under pressure for using Ramist philosophical methods, familiar to him from his time at Leiden. Arminius was publicly forbidden to teach Ramean philosophy. After this difficult state of affairs, he moved to Basel to continue his studies.

He continued to distinguish himself there as an excellent student. In 1583 Arminius was contemplating a return to Geneva when the theological faculty at Basel spontaneously offered him a doctorate. He declined the honor on account of his youth (he was about 24) and returned to the school in Geneva to finish his schooling in Geneva under Beza.

Commendations from Beza and Grynaeus

Upon the conclusion of Arminius' studies and a request for him to pastor in Amsterdam, Beza replied to leaders in Amsterdam with this letter:

"...Let it be known to you that from the time Arminius returned to us from Basel, his life and learning both have so approved themselves to us, that we hope for the best from him in every respect, if he steadily persists in the same course, which, by the blessing of God, we doubt not he will; for, among other endowments, God has given him an intellect well-suited both to the apprehension and to the discrimination of things. If this henceforward be regulated by piety, which he appears assiduously to cultivate, it cannot but happen that this power of intellect, when consolidated by mature age and experience, will be productive of the richest fruits. Such is our opinion of Arminius — a young man, unquestionably, so far as we are able to judge, most worthy of your kindness and liberality" (Letter of 3 June 1585 from Beza to Amsterdam).

From this letter it would seem that the earlier tension from Arminius' attraction to Ramist philosophy had dissipated and Arminius was known even to Beza as an excellent though budding theologian. Three months later, John Grynaeus at the University of Basel sent this letter of commendation:

"To pious readers, greeting: 'Inasmuch as a faithful testimonial of learning and piety ought not to be refused to any learned and pious man, so neither to James Arminius, a native of Amsterdam [sic], for his deportment while he attended the University of Basel was marked by piety, moderation, and assiduity in study ; and very often, in the course of our theological discussions, he made his gift of a discerning spirit so manifest to all of us, as to elicit from us well-merited congratulations. More recently, too, in certain extraordinary prelections delivered with the consent, and by the order, of the Theological Faculty, in which he publicly expounded a few chapters of the Epistle to the Romans, he gave us the best ground to hope that he was destined erelong — if, indeed, he goes on to stir up the gift of God that is in him — to undertake and sustain the function of teaching, to which he may be lawfully set apart, with much fruit to the Church. I commend him, accordingly, to all good men, and, in particular, to the Church of God in the famous city of Amsterdam ; and I respectfully entreat that regard may be had to that learned and pious youth, so that he may never be under the necessity of intermitting theological studies which have been thus far so happily prosecuted. Farewell ! 'John James Grynaeus, Professor of Sacred Literature, and Dean of the Theological Faculty. — Written with mine own hand. Basle, 3rd September, 1583."

Beginning of public ministry

Arminius answered the call to pastor at Amsterdam in 1587, delivering Sunday and midweek sermons. After being tested by the church leaders, he was ordained in 1588. He gained a reputation as a good preacher and faithful pastor.

One of Arminius' first tasks was given to him by Ecclesiastical Court of Amsterdam; namely, to refute the teachings of Dirck Volckertszoon Coornhert, who rejected Beza's supralapsarian doctrine of God's absolute and unconditional decree to create men so as to save some. The discussion had already begun with two ministers at Delft who had written "An Answer to certain Arguments of Beza and Calvin, from a Treatise on Predestination as taught in the Ninth Chapter of Romans" a document which contradicted both Beza and Coornhert. They proposed that although God's decree to save only some was indeed absolute and unconditional, it had occurred after the fall (proposing infralapsarianism rather than Beza's supralapsarianism). Arminius was tasked with refuting both Coornhert and infralapsarianism theology. He readily agreed to the task, but after greater study found himself in conflict over the matter. He determined to spend greater time in study before continuing his refutation.

In 1590 he married Lijsbet Reael, the daughter of Laurens Jacobsz Reael, a prominent merchant and poet in Amsterdam who also helped lead the Protestant Reformation and later helped establish the first Reformed Church in the area. Arminius's marriage to Reael allowed him access to her prestigious connections, and he made many friends in the merchant industry and high society. He was commissioned to organize the educational system of Amsterdam, and is said to have done it well. He greatly distinguished himself by faithfulness to his duties in 1602 during a plague that swept through Amsterdam, going into infected houses that others did not dare to enter in order to give them water, and supplying their neighbors with funds to care for them.

Professor at Leiden

In 1603 he was called back to Leiden University to teach theology. This came about after almost simultaneous deaths in 1602 of two faculty members, Franciscus Junius and Lucas Trelcatius the elder, in an outbreak of plague. Lucas Trelcatius the younger and Arminius (despite Plancius' protest) were appointed, the decision resting largely with Franciscus Gomarus, the surviving faculty member. While Gomarus cautiously approved Arminius, whose views were already suspected of unorthodoxy, his arrival opened a period of debate rather than closed it. The appointment had also a political dimension, being backed by both Johannes Uytenbogaert at The Hague and Johan van Oldenbarnevelt.

Final debate and last days

Arminius remained as a teacher at Leiden until his death, and was valued by his students. Still, the conflict with Gomarus widened out into a large-scale split within Calvinism. Of the local clergy, Adrianus Borrius supported Arminius, while Festus Hommius opposed him. Close friends, students and supporters of Arminius included Johannes Drusius, Conrad Vorstius, Anthony Thysius, Johannes Halsbergius, Petrus Bertius, Johannes Arnoldi Corvinus, the brothers Rembert and Simon Episcopius. His successor at Leiden (again selected with the support of Uytenbogaert and Oldenbarnevelt) was Vorstius, a past influence on Arminius by his writings.

Once again the States attempted to tamp down the growing controversy without calling a synod. Arminius was ordered to attend another conference with Gomarus in The Hague in on 13–14 August 1609. When the conference was to reconvene on 18 August, Arminius' health began to fail and so he returned to Leiden. The States suspended the conference and asked both men for a written reaction to their adversary's viewpoint.

Arminius died on 19 October 1609 at his house at the Pieterskerkhof. He was buried in the Pieterskerk at Leiden, where a memorial stone on his behalf was placed in 1934.

Theology and legacy

In attempting to defend Calvinistic predestination against the teachings of Dirck Volckertszoon Coornhert, Arminius began to doubt aspects of Calvinism and modified some parts of his own view. He attempted to reform Calvinism, and lent his name to a movement—Arminianism—which resisted some of the Calvinist tenets (unconditional election, the nature of the limitation of the atonement, and irresistible grace). The early Dutch followers of his teaching became known as Remonstrants after they issued a document containing five points of disagreement with mainstream Calvinism, entitled Remonstrantiæ (1610).

Arminius wrote that he sought to teach only those things which could be proved from the Scriptures and that tended toward edification among Christians (with the exception of Roman Catholics, with whom he said there could be no spiritual accord). His motto was reputed to be "Bona conscientia paradisus", meaning, "A good conscience is a paradise."

Arminius taught of a "preventing" (or prevenient) grace that has been conferred upon all by the Holy Spirit and this grace is "sufficient for belief, in spite of our sinful corruption, and thus for salvation." Arminius stated that "the grace sufficient for salvation is conferred on the Elect, and on the Non-elect; that, if they will, they may believe or not believe, may be saved or not be saved." William Witt states that "Arminius has a very high theology of grace. He insists emphatically that grace is gratuitous because it is obtained through God's redemption in Christ, not through human effort."

The theology of Arminianism did not become fully developed during Arminius' lifetime, but after his death (1609) the Five articles of the Remonstrants (1610) systematized and formalized the ideas. But the Calvinist Synod of Dort (1618–19), convening for the purpose of condemning Arminius' theology, declared it and its adherents anathemas, defined the five points of Calvinism, and persecuted Arminian pastors who remained in the Netherlands. But in spite of persecution, "the Remonstrants continued in Holland as a distinct church and again and again where Calvinism was taught Arminianism raised its head."

Publishers in Leiden (1629) and at Frankfurt (1631 and 1635) issued the works of Arminius in Latin.

John Wesley (1703–91), the founder of the Methodist Movement, came to his own religious beliefs while in college and through his Aldersgate Experience or epiphany and expressed himself strongly against the doctrines of Calvinistic election and reprobation. His system of thought has become known as Wesleyan Arminianism, the foundations of which were laid by Wesley and his fellow preacher John William Fletcher. Although Wesley knew very little about the beliefs of Jacobus Arminius and arrived at his religious views independently of Arminius, Wesley acknowledged late in life, with the 1778 publication of The Arminian Magazine, that he and Arminius were in general agreement. Theology Professor W. Stephen Gunther concludes he was "a faithful representative" of Arminius' beliefs. Wesley was perhaps the clearest English proponent of Arminianism. He embraced Arminian theology and became its most prominent champion. Today[update], the majority of Methodists remain committed (knowingly or unknowingly) to Arminian theology, and Arminianism itself has become one of the dominant theological systems in the United States, thanks in large part to the influence of John and Charles Wesley.

Personal life

Arminius and his wife Lijsbet Laurensdochtor Reael, who married in 1590, had a total of 12 children, three of whom died young during infancy. They had ten sons; Harmen (b. 1594), Pieter (b. 1596), Jan (b. 1598), Laurens (b. 1600, died in infancy), Laurens (b. 1601), Jacob (b. 1603), Willem (b. 1605), and Daniel (b. 1606). They had two other sons who also died in infancy, whose names are not part of the public record. Their daughters were Engelte (b. 1593) and Geertruyd (b. 1608). He was survived by his wife and children when he died.

See also

In Spanish: Jacobo Arminio para niños

In Spanish: Jacobo Arminio para niños