Iron Tail facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Iron Tail

|

|

|---|---|

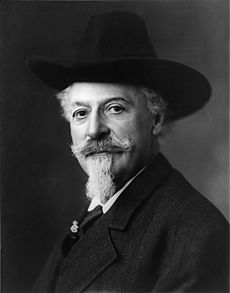

Iron Tail in 1905

|

|

| Born | 1842 |

| Died | May 29, 1916 (aged 73–74) |

| Nationality | Oglala Lakota |

| Occupation | Wild Wester |

| Known for | Oglala Lakota chief, model for the Buffalo nickel |

Iron Tail (Oglala Lakota: Siŋté Máza in Standard Lakota Orthography; 1842 – May 29, 1916) was an Oglala Lakota Chief and a star performer with Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Iron Tail was one of the most famous Native American celebrities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and a popular subject for professional photographers who circulated his image across the continents. Iron Tail is notable in American history for his distinctive profile on the Buffalo nickel or Indian Head nickel of 1913 to 1938.

Contents

Early life and family

Siŋté Máza was the Chief's tribal name. Asked why the white people call him Iron Tail, he said that when he was a baby his mother saw a band of warriors chasing a herd of buffalo, in one of their periodic grand hunts, their tails standing upright as if shafts of steel, and she thereafter called his name Siŋté Máza as something new and novel.

Iron Tail and Iron Hail

Chief Iron Tail is often mistaken by historians for Chief Iron Hail ("Dewey Beard"), being Lakota contemporaries with similar sounding names. Most biographies incorrectly report that Iron Tail fought in the Battle of the Little Bighorn and that his family was killed in 1890 at Wounded Knee, when in truth it was Iron Hail who suffered the loss. Major Israel McCreight reported: "Iron Tail was not a war chief and no remarkable record as a fighter. He was not a medicine man or conjuror, but a wise counselor and diplomat, always dignified, quiet and never given to boasting. He seldom made a speech and cared nothing for gaudy regalia, very much like the famed War Chief Crazy Horse. In this respect he always had a smile and was fond of children, horses and friends."

Iron Tail and Buffalo Bill

Iron Tail was an international personality and appeared as the lead with Buffalo Bill at the Champs-Élysées in Paris, France, and the Colosseum in Rome, Italy. In France, as in England, Buffalo Bill and Iron Tail were feted by the aristocracy. Iron Tail was one of Buffalo Bill's best friends and they hunted elk and bighorn together on annual trips. On one of his visits to The Wigwam of Major Israel McCreight, Buffalo Bill asked Iron Tail to illustrate in pantomime how he played and won a game of poker with US army officials during a Treaty Council in the old days. "Going through all the forms of the game from dealing to antes and betting and drawing a last card during which no word was uttered and his countenance like a statue, he suddenly swept the table clean into his blanket and rose from the table and strutted away. It was a piece of superb acting, and exceedingly funny." Iron Tail continued to travel with Buffalo Bill until 1913, and then the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West until his death in 1916.

Iron Tail and Gertrude Käsebier

Photographing the Sioux

Gertrude Käsebier was one of the most influential American photographers of the early 20th century and best known for her evocative images of Native Americans. Käsebier spent her childhood on the Great Plains living near and playing with Sioux children. In 1898, Käsebier watched Buffalo Bill's Wild West troupe parade past her Fifth Avenue studio in New York City, toward Madison Square Garden. Her memories of affection and respect for the Lakota people inspired her to send a letter to Buffalo Bill requesting permission to photograph Sioux traveling with the show in her studio. Buffalo Bill and Käsebier were similar in their abiding Native American culture and maintained friendships with the Sioux. Buffalo Bill quickly approved Käsebier's request and she began her project on Sunday morning, April 14, 1898. Käsebier's project was purely artistic and her images were not made for commercial purposes and never used in Buffalo Bill's Wild West program booklets or promotional posters.

A session with Chief Iron Tail

Käsebier took classic photographs of the Sioux while they were relaxed. Chief Iron Tail was one of Käsebier's most challenging portrait subjects. Käsebier's session with Iron Tail was her only recorded story: "Preparing for their visit to Käsebier's photography studio, the Sioux at Buffalo Bill's Wild West Camp met to distribute their finest clothing and accessories to those chosen to be photographed." Käsebier admired their efforts, but desired to, in her own words, photograph a "real raw Indian, the kind I used to see when I was a child', referring to her early years in Colorado and on the Great Plains. Käsebier selected one Indian, Iron Tail, to approach for a photograph without regalia. He did not object. The resulting photograph was exactly what Käsebier had envisioned: a relaxed, intimate, quiet, and beautiful portrait of the man, devoid of decoration and finery, presenting himself to her and the camera without barriers. Several days later, Iron Tail was given the photograph and he immediately tore it up, stating that it was too dark. Käsebier re-photographed him, this time in his full feather headdress, much to his satisfaction.

Chief Iron Tail was an international celebrity. He appeared with his fine regalia as the lead with Buffalo Bill at the Avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris, France, and the Colosseum of Rome. Iron Tail was a superb showman and chaffed at the photo of him relaxed. but Käsebier chose it as the frontispiece for a 1901 Everybody's Magazine article. Käsebier believed all the portraits were a "revelation of Indian character," showing the strength and individual character of the Native Americans in "new phases for the Sioux."

The Indian on the nickel

Early in the twentieth century, Iron Tail's distinctive profile became well known across the United States as one of three models for the five-cent coin Buffalo nickel or Indian Head nickel. The popular coin was introduced in 1913 and showcases the native beauty of the American West. Bee Ho Gray, the famous Wild West performer, accompanied Iron Tail to act as an interpreter and guide to Washington D.C. and New York where Iron Tail modeled for sculptor James Earle Fraser as he worked on designs for the new Buffalo nickel. Iron Tail was the most famous Native American of his day and a popular subject for professional photographers who circulated his image across the continents.

Iron Tail and Major Israel McCreight

Chief Iron Tail was a friend of Major Israel McCreight and a frequent visitor to The Wigwam in DuBois, Pennsylvania. Iron Tail and Chief Flying Hawk considered The Wigwam their home in the East. On June 22, 1908, Iron Tail presided over a ceremony at the tent of Buffalo Bill adopting McCreight as an honorary Chief of the Oglala Lakota. In 1915, McCreight hosted a grand reception for Iron Tail and Flying Hawk at The Wigwam.

Adoption of Čhaŋté Tȟáŋka

On June 22, 1908, Iron Tail and "Buffalo Bill" Cody visited Du Bois, Pennsylvania with the Wild West Congress of Rough Riders. Twelve thousand people a day attended Cody's Wild West performances and 150 Oglalas were in town with 150 ponies. On this occasion, Iron Tail presided over the adoption of Major Israel McCreight as an honorary Chief of the Oglala Lakota and named McCreight "Čhaŋté Tȟáŋka ("Great Heart"). Iron Tail performed the ceremony assembled at Buffalo Bill's tent and attended by Chief American Horse, Chief Whirlwind Horse, Chief Lone Bear and 100 Oglala Lakota members of the Wild West Congress of Rough Riders. The Oglala Lakota chiefs formed a small circle around McCreight and his wife Alice, and Iron Tail began the ceremony with a speech in Lakota, a hearty handshake all around, and then placed a war bonnet McCreight's head and moccasins upon his feet. Iron Tail then presented McCreight with a tepee on which an owl had been traced with yellow chalk and told this was for him and Alice to live in. Tom-tom drums were then beaten and tribal songs put up vigorously. Concluding remarks were made by Iron Tail ending with hearty handshakes. Iron Tail and Buffalo Bill were loaded into a new 1908 Rambler touring car and driven to McCreight's town house for the banquet which followed. There, Iron Tail was presented with a new Winchester rifle as a souvenir of the event. McCreight was forever moved by the solemnity of the occasion, and carried the honor proudly and with distinction the rest of his life. McCreight later remarked that the title, honorary Chief of the Oglala Lakota, was a far greater tribute than could have been conferred by any president or military organization.

Final days

In May 1916, Chief Iron Tail, at the age of 74, became ill with pneumonia while performing with the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and was placed in St. Luke's Hospital. Buffalo Bill was obliged to go on with his show next day to Baltimore, Maryland, and Iron Tail was left alone in a strange city with doctors and nurses who could not communicate with him. McCreight learned about the Chief's admission to the hospital in the morning Philadelphia paper, and immediately sent a telegram to Buffalo Bill to send Iron Tail by next train to Du Bois, Pennsylvania, for care at The Wigwam. No reply was had and the wire was not delivered or forwarded to Baltimore. Instead the hospital authorities put Iron Tail on a Pullman, ticketed for home to the Black Hills. On May 28, 1916, when the porter of his car went to wake him at South Bend, Indiana, Iron Tail was dead, his body continuing on to its destination. Buffalo Bill expressed regret that the Chief was sent to the hospital and that he had not received the telegram. Iron Tail's body was transferred to a hospital in Rushville, Nebraska, then to Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, where he was buried at Holy Rosary Mission Cemetery on June 3, 1916. With deep emotion, Buffalo Bill said he was going to put a granite stone on Iron Tail's grave with a replica of the Buffalo nickel (for which Iron Tail had posed) carved on it as a memento. However, Buffalo Bill died on January 10, 1917, just six months after Iron Tail's death. In a ceremony at Buffalo Bill's grave on Lookout Mountain, west of Denver, Colorado, Chief Flying Hawk laid his war staff of eagle feathers on the grave. Each of the veteran Wild Westers placed a Buffalo nickel on the imposing stone as a symbol of the Indian, the buffalo, and the scout, figures since the 1880s that were symbolic of the early history of the American West.