Indonesian occupation of East Timor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Indonesian occupation of East Timor |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War (until 1991) | |||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

East Timorese Resistance Groups

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 250,000 troops | 27,000 (including non combatant in 1975) 1,900 (including non combatant in 1999) 12,538 fighters (1975–1999) |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,277 soldiers and police killed 1,527 Timorese militia killed 2,400 wounded Total: 3,408 killed and 2,400 wounded |

11,907 fighters killed (1975–1999) | ||||||

| Estimates range from 100,000–300,000 civilians dead (see below) | |||||||

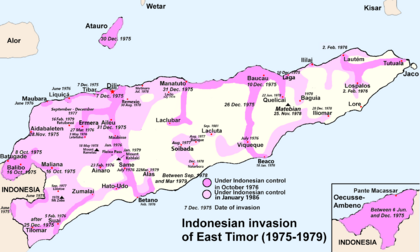

The Indonesian occupation of East Timor began in December 1975 and lasted until October 1999. After centuries of Portuguese colonial rule in East Timor, the 1974 Carnation Revolution in Portugal led to the decolonisation of its former colonies, creating instability in East Timor and leaving its future uncertain. After a small-scale civil war, the pro-independence Fretilin declared victory in the capital city of Dili and declared an independent East Timor on 28 November 1975.

Following the "Balibo Declaration" that was signed by representatives of Apodeti, UDT, KOTA and the Trabalhista Party on 30 November 1975, Indonesian military forces invaded East Timor on 7 December 1975, and by 1979 they had all but destroyed the armed resistance to the occupation. On 17 July 1976, Indonesia formally annexed East Timor as its 27th province and declared the province of Timor Timur (East Timor).

Immediately after the invasion, the United Nations General Assembly and Security Council passed resolutions condemning Indonesia's actions in East Timor and calling for its immediate withdrawal from the territory. Australia and Indonesia were the only nations in the world which recognised East Timor as a province of Indonesia, and soon afterwards they began negotiations to divide resources found in the Timor Gap. Other governments, including those of the United States, Japan, Canada and Malaysia, also supported the Indonesian government. The invasion of East Timor and the suppression of its independence movement, however, caused great harm to Indonesia's reputation and international credibility.

For twenty-four years, the Indonesian government subjected the people of East Timor to routine and systematic internment, extrajudicial executions, massacres, and starvation. Resistance to Indonesian rule remained strong; in 1996 the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to two men from East Timor, Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo and José Ramos-Horta, for their ongoing efforts to peacefully end the occupation. A 1999 vote to determine East Timor's future resulted in an overwhelming majority in favour of independence, and in 2002 East Timor became an independent nation. The Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor estimated the number of deaths during the occupation from famine and violence to be between 90,800 and 202,600.

After the 1999 vote for independence, paramilitary groups working with the Indonesian military undertook a final wave of violence during which most of the country's infrastructure was destroyed. The Australian-led International Force for East Timor restored order, and following the departure of Indonesian forces from East Timor, the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor administered the territory for two years, establishing a Serious Crimes Unit to investigate and prosecute crimes committed in 1999. Its limited scope and the small number of sentences delivered by Indonesian courts have caused numerous observers to call for an international tribunal for East Timor.

Oxford University held an academic consensus calling the occupation of East Timor a genocide and Yale University teaches it as part of its Genocide Studies program.

Contents

Background

The Portuguese first arrived in Timor in the 16th century, and in 1702 East Timor came under Portuguese colonial administration. Portuguese rule was tenuous until the island was divided with the Dutch Empire in 1860. A significant battleground during the Pacific War, East Timor was occupied by 20,000 Japanese troops. The fighting helped prevent a Japanese occupation of Australia but resulted in 60,000 East Timorese deaths.

When Indonesia secured its independence after World War II under the leadership of Sukarno, it did not claim control of East Timor, and aside from general anti-colonial rhetoric, it did not oppose Portuguese control of the territory. A 1959 revolt in East Timor against the Portuguese was not endorsed by the Indonesian government. A 1962 United Nations document notes: "the government of Indonesia has declared that it maintains friendly relations with Portugal and has no claim to Portuguese Timor...". These assurances continued after Suharto took power in 1965. An Indonesian official declared in December 1974: "Indonesia has no territorial ambition... Thus there is no question of Indonesia wishing to annex Portuguese Timor."

In 1974, 1974 Carnation Revolution in Portugal caused significant changes in Portugal's relationship with its colony in Timor. The power shift in Europe invigorated movements for independence in colonies like Mozambique and Angola, and the new Portuguese government began a decolonisation process for East Timor. The first of these was an opening of the political process.

Fretilin, UDT, and APODETI

When East Timorese political parties were first legalised in April 1974, three groupings emerged as significant players in the post-colonial landscape. The União Democrática Timorense (Timorese Democratic Union, or UDT), was formed in May by a group of wealthy landowners. Initially dedicated to preserving East Timor as a protectorate of Portugal, in September UDT announced its support for independence. A week later, the Frente Revolucionária de Timor-Leste Independente (Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor, or Fretilin) appeared. Initially organised as the ASDT (Associacão Social Democrata Timorense), the group endorsed "the universal doctrines of socialism", as well as "the right to independence". As the political process grew more tense, however, the group changed its name and declared itself "the only legitimate representative of the people". The end of May saw the creation of a third party, Associacão Popular Democratica Timorense (Timorese Popular Democratic Association, or APODETI). Advocating East Timor's integration with Indonesia and originally named Associacão Integraciacao de Timor Indonesia (Association for the Integration of Timor into Indonesia), APODETI expressed concerns that an independent East Timor would then be economically weak and vulnerable.

Indonesian nationalist and military hardliners, particularly leaders of the intelligence agency Kopkamtib and special operations unit, Kopassus, saw the Portuguese revolution as an opportunity for East Timor's integration with Indonesia. The central government and military feared that an East Timor governed by leftists could be used as a base for incursions by unfriendly powers into Indonesia, and also that an independent East Timor within the archipelago could inspire secessionist sentiments within Indonesian provinces. The fear of national disintegration was played upon military leaders close to Suharto and remained as one of Indonesia's strongest justifications for refusing to entertain the prospect of East Timorese independence or even autonomy until the late 1990s. The military intelligence organisations initially sought a non-military annexation strategy, intending to use APODETI as its integration vehicle.

In January 1975, UDT and Fretilin established a tentative coalition dedicated to achieving independence for East Timor. At the same time, the Australian government reported that the Indonesian military had conducted a "pre-invasion" exercise at Lampung. For months, the Indonesian Special Operations command, Kopassus, had been covertly supporting APODETI through Operasi Komodo (Operation Komodo, named after the lizard). By broadcasting accusations of communism among Fretilin leaders and sowing discord in the UDT coalition, the Indonesian government fostered instability in East Timor and, observers said, created a pretext for invading. By May tensions between the two groups caused UDT to withdraw from the coalition.

In an attempt to negotiate a settlement to the dispute over East Timor's future, the Portuguese Decolonization Commission convened a conference in June 1975 in Macau. Fretilin boycotted the meeting in protest of APODETI's presence; representatives of UDT and APODETI complained that this was an effort to obstruct the decolonisation process. In his 1987 memoir Funu: The Unfinished Saga of East Timor, Fretilin leader José Ramos-Horta recalls his "vehement protests" against his party's refusal to attend the meeting. "This", he writes, "was one of our tactical political errors for which I could never find an intelligent explanation."

Coup, civil war, and independence declaration

The tension reached a boiling point in mid-1975 when rumours began circulating of possible power seizures from both independence parties. In August 1975, UDT staged a coup in the capital city Dili, and a small-scale civil war broke out. Ramos-Horta describes the fighting as "bloody", and details violence committed by both UDT and Fretilin. He cites the International Committee of the Red Cross, which counted 2,000–3,000 people dead after the war. The fighting forced the Portuguese government onto the nearby island of Atauro. Fretilin defeated UDT's forces after two weeks, much to the surprise of Portugal and Indonesia. UDT leaders fled to Indonesian-controlled West Timor. There they signed a petition on 7 September calling for East Timor's integration with Indonesia; most accounts indicate that UDT's support for this position was forced by Indonesia.

Once they had gained control of East Timor, Fretilin faced attacks from the west, by Indonesian military forces—then known as Angkatan Bersenjata Republik Indonesia (ABRI)—and by a small group of UDT troops. Indonesia captured the border city of Batugadé on 8 October 1975; nearby Balibó and Maliana were taken eight days later. During the Balibó raid, members of an Australian television news crew—later dubbed the "Balibo Five"—were killed by Indonesian soldiers. The deaths, and subsequent campaigns and investigations, attracted international attention and rallied support for East Timorese independence.

At the start of November, the foreign ministers from Indonesia and Portugal met in Rome to discuss a resolution of the conflict. Although no Timorese leaders were invited to the talks, Fretilin sent a message expressing their desire to work with Portugal. The meeting ended with both parties agreeing that Portugal would meet with political leaders in East Timor, but the talks never took place. In mid-November, Indonesian forces began shelling the city of Atabae from the sea and captured it by the end of the month.

Frustrated by Portugal's inaction, Fretilin leaders believed they could ward off Indonesian advances more effectively if they declared an independent East Timor. National Political Commissioner Mari Alkatiri conducted a diplomatic tour of Africa, gathering support from governments there and elsewhere.

According to Fretilin, this effort yielded assurances from twenty-five countries—including the People's Republic of China, the Soviet Union, Mozambique, Sweden, and Cuba—to recognise the new nation. Cuba currently shares close relations with East Timor today. On 28 November 1975, Fretilin unilaterally declared independence for the Democratic Republic of East Timor. Indonesia announced UDT and APODETI leaders in and around Balibó would respond the next day by declaring that region independent from East Timor and officially part of Indonesia. This Balibo Declaration, however, was drafted by Indonesian intelligence and signed on Bali; later this was described by some as the 'Balibohong Declaration', a pun on the Indonesian word for 'lie'. Portugal rejected both declarations, and the Indonesian government approved military action to begin its annexation of East Timor.

Invasion

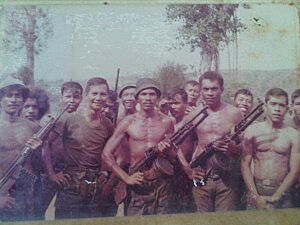

On 7 December 1975, Indonesian forces invaded East Timor. Operasi Seroja (Operation Lotus) was the largest military operation ever carried out by that nation. Troops from Fretilin's military organisation Falintil engaged ABRI forces in the streets of Dili and reported 400 Indonesian paratroopers were killed as they descended into the city. Angkasa Magazine reports 35 dead Indonesian troops and 122 from the Fretilin side. By the end of the year, 10,000 troops occupied Dili, and another 20,000 had been deployed throughout East Timor. Massively outnumbered, Falintil troops fled to the mountains and continued guerrilla combat operations.

Indonesian hegemony

On 17 December, Indonesia formed the Provisional Government of East Timor (PSTT) which was headed by Arnaldo dos Reis Araújo of APODETI as president and Lopez da Cruz of UDT. Most sources describe this institution as a creation of the Indonesian military. One of PSTT's first activities was the formation of a "Popular Assembly" consisting of elected representatives and leaders "from various walks of Timorese life". Like the PSTT itself, the Popular Assembly is usually characterised as an instrument of propaganda created by the Indonesian military; although international journalists were invited to witness the group's meeting in May 1976, their movement was tightly constrained. The Assembly drafted a request for formal integration into Indonesia, which Jakarta described as "the act of self-determination" in East Timor.

Indonesia kept East Timor shut off from the rest of the world, except for a few years in the late 1980s and early 1990s, claiming that the vast majority of East Timorese supported integration. This position was followed closely by the Indonesian media such that an East Timorese acceptance of their integration with Indonesia was taken for granted by, and was a non-issue for, the majority of Indonesians. East Timor came to be seen as a training ground for the officer corps in tactics of suppression for Aceh and Irian Jaya and was pivotal in ensuring military sector dominance of Indonesia.

Indonesian campaigns against the resistance

Leaders of Indonesian intelligence influential with Suharto had initially envisaged that invasion, subdual of Fretilin resistance, and integration with Indonesia would be quick and relatively painless. The ensuing Indonesian campaigns up through 1976 were devastating for the East Timorese, an enormous drain on Indonesian resources, were severely damaging to Indonesia internationally, and ultimately a failure.

By the end of 1976, a stalemate existed between the Falintil and the Indonesian army. Unable to overcome massive resistance and drained of its resources, the TNI began rearming. The Indonesian navy ordered missile-firing patrol-boats from the United States, Australia, the Netherlands, South Korea, and Taiwan, as well as submarines from West Germany. In February 1977, Indonesia also received thirteen OV-10 Bronco aircraft from the Rockwell International Corporation with the aid of an official US government foreign military aid sales credit. The Bronco was ideal for the East Timor invasion, as it was specially designed for counter-insurgency operations in steep terrain. By the beginning of February 1977, at least six of the 13 Broncos were operating in East Timor and helped the Indonesian military pinpoint Fretilin positions. The OV-10 Broncos dealt a heavy blow to the Falintil when the aircraft attacked their forces with conventional weapons and Soviet-supplied Napalm known as 'Opalm.' Along with the new weaponry, an additional 10,000 troops were sent in to begin new campaigns that would become known as the 'final solution'.

TNI strategists implemented a strategy of attrition against the Falintil beginning in September 1977. This was accomplished by rendering the central regions of East Timor unable to sustain human life through napalm attacks, chemical warfare and destruction of crops. This was to be done in order to force the population to surrender into the custody of Indonesian forces and deprive the Falintil of food and population. Catholic officials in East Timor called this strategy an "encirclement and annihilation" campaign. 35,000 ABRI troops surrounded areas of Fretilin support and killed civilians. Air and naval bombardments were followed by ground troops, who destroyed villages and agricultural infrastructure. Thousands of people may have been killed during this period.

During this period, allegations of Indonesian use of chemical weapons arose, as villagers reported maggots appearing on crops after bombing attacks. Fretilin radio claimed Indonesian planes dropped chemical agents, and several observers—including the Bishop of Dili—reported seeing napalm dropped on the countryside. The UN's Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor, based on interviews with over 8,000 witnesses, as well as Indonesian military papers and intelligence from international sources, confirmed that the Indonesians used chemical weapons and napalm to poison food and water supplies in Fretilin controlled areas during the "encirclement and annihilation" campaign.

While brutal, the Indonesian 'encirclement and annihilation' campaign of 1977–1978 was effective in that it broke the back of the main Fretilin militia. The capable Timorese president and military commander, Nicolau Lobato, was killed by helicopter-borne Indonesian troops on 31 December 1978.

Resettlement and enforced starvation

As a result of the destruction of food crops, many civilians were forced to leave the hills and surrender to the TNI. Often, when surviving villagers came down to lower-lying regions to surrender, the military would execute them. Those who were not killed outright by TNI troops were sent to receiving centres for vetting, which had been prepared in advance in the vicinity of local TNI bases. In these transit camps, the surrendered civilians were registered and interrogated. Those who were suspected of being members of the resistance were killed.

These centres were often constructed of thatch huts with no toilets. Additionally, the Indonesian military barred the Red Cross from distributing humanitarian aid, and no medical care was provided to the detainees. As a result, many of the Timorese – weakened by starvation and surviving on small rations given by their captors – died of malnutrition, cholera, diarrhoea and tuberculosis. By late 1979, between 300,000 and 370,000 Timorese had passed through these camps. After three months, the detainees were resettled in "strategic hamlets" where they were imprisoned and subjected to enforced starvation. Those in the camps were prevented from travelling and cultivating farmland and were subjected to a curfew. The UN truth commission report confirmed the Indonesian military's use of enforced starvation as a weapon to exterminate the East Timorese civilian population, and that large numbers of people were "positively denied access to food and its sources". The report cited testimony from individuals who were denied food and detailed destruction of crops and livestock by Indonesian soldiers. It concluded that this policy of deliberate starvation resulted in the deaths of 84,200 to 183,000 Timorese. One church worker reported five hundred East Timorese dying of starvation every month in one district.

World Vision Indonesia visited East Timor in October 1978 and claimed that 70,000 East Timorese were at risk of starvation. An envoy from the International Committee of the Red Cross reported in 1979 that 80% of one camp's population was malnourished, in a situation that was "as bad as Biafra". The ICRC warned that "tens of thousands" were at risk of starvation. Indonesia announced that it was working through the government-run Indonesian Red Cross to alleviate the crisis, but the NGO Action for World Development charged that organisation with selling donated aid supplies.

Operasi Keamanan: 1981–82

In 1981 the Indonesian military launched Operasi Keamanan (Operation Security), which some have named the "fence of legs" program. During this operation, Indonesian forces conscripted 50,000 to 80,000 Timorese men and boys to march through the mountains ahead of advancing TNI troops as human shields to foreclose a Fretilin counterattack. The objective was to sweep the guerillas into the central part of the region where they could be eradicated. Many of those conscripted into the "fence of legs" died of starvation or exhaustion. The operation failed to crush the resistance, and widespread resentment toward the occupation grew stronger than ever. As Fretilin troops in the mountains continued their sporadic attacks, Indonesian forces carried out numerous operations to destroy them over the next ten years. In the cities and villages, meanwhile, a non-violent resistance movement began to take shape.

'Operation Clean-Sweep': 1983

The failure of successive Indonesian counterinsurgency campaigns led the Indonesian military elite to instruct the commander of the Dili-based Sub regional Military Resort Command, Colonel Purwanto to initiate peace talks with Fretilin commander Xanana Gusmão in a Fretilin-controlled area in March 1983. When Xanana sought to invoke Portugal and the UN in the negotiations, ABRI Commander Benny Moerdani broke the ceasefire by announcing a new counterinsurgency offensive called "Operational Clean-Sweep" in August 1983, declaring, "This time no fooling around. This time we are going to hit them without mercy."

The breakdown of the ceasefire agreement was followed by a renewed wave of massacres, summary executions and "disappearances" at the hands of Indonesian forces.

Demography and economy

The Portuguese language was banned in East Timor and Indonesian was made the language of government, education and public commerce, and the Indonesian school curriculum was implemented. The official Indonesian national ideology, Pancasila, was applied to East Timor and government jobs were restricted to those holding certification in Pancasila training. East Timorese animist belief systems did not fit with Indonesia's constitutional monotheism, resulting in mass conversions to Christianity. Portuguese clergy were replaced with Indonesian priests, and Latin and Portuguese mass were replaced by Indonesian mass. Before the invasion, only 20% of East Timorese were Roman Catholics, and by the 1980s, 95% were registered as Catholics. With over 90% Catholic population, East Timor is currently one of the most densely Catholic countries in the world.

East Timor was a particular focus for the Indonesian government's transmigration program, which aimed to resettle Indonesians from densely to less populated regions. Media censorship under the "New Order" meant that the state of conflict in East Timor was unknown to the transmigrants, predominantly poor Javanese and Balinese wet-rice farmers. On arrival, they found themselves under the ongoing threat of attack by East Timorese resistance fighters, and became the object of local resentment, since large tracts of land belonging to East Timorese had been compulsorily appropriated by the Indonesian government for transmigrant settlement. Although many gave up and returned to their island of origin, those migrants that stayed in East Timor contributed to the "Indonesianisation" of East Timor's integration. 662 transmigrant families (2,208 people) settled in East Timor in 1993, whereas an estimated 150,000 free Indonesian settlers lived in East Timor by the mid-1990s, including those offered jobs in education and administration. Migration increased resentment amongst Timorese who were overtaken by more business savvy immigrants.

Following the invasion, Portuguese commercial interests were taken over by Indonesians. The border with West Timor was opened resulting in an influx of West Timorese farmers, and in January 1989 the territory was open to private investment. Economic life in the towns was subsequently brought under the control of entrepreneurial Bugis, Makassarese, and Butonese immigrants from South Sulawesi, while East Timor products were exported under partnerships between army officials and Indonesian businessmen. Denok, a military-controlled firm, monopolised some of East Timor's most lucrative commercial activities, including sandal wood export, hotels, and the import of consumer products. The group's most profitable business, however, was its monopoly on the export of coffee, which was the territory's most valuable cash crop. Indonesian entrepreneurs came to dominate non-Denok/military enterprises, and local manufactures from the Portuguese period made way for Indonesian imports.

The Indonesian government's primary response to criticism of its policies was to highlight its funding of development in East Timor's health, education, communications, transportation, and agriculture. East Timor, however, remained poor following centuries of Portuguese colonial neglect and Indonesian critic George Aditjondro points out that conflict in the early years of occupation leads to sharp drops in rice and coffee production and livestock populations. Other critics argue that infrastructure development, such as road construction, is often designed to facilitate Indonesian military and corporate interests. While the military controlled key businesses, private investors, both Indonesian and international, avoided the territory. Despite improvements since 1976, a 1993 Indonesian government report estimated that in three-quarters of East Timor's 61 districts, more than half lived in poverty.

1990s

Changing resistance and integration campaigns

Major investment by the Indonesian government to improve East Timor's infrastructure, health and education facilities since 1975 did not end East Timorese resistance to Indonesian rule. Although by the 1980s Fretilin forces had dropped to a few hundred armed men, Fretilin increased its contacts with young Timorese especially in Dili, and an unarmed civil resistance seeking self-determination took shape. Many of those in the protest movements were young children at the time of the invasion and had been educated under the Indonesian system. They resented the repression and replacement of Timorese cultural and political life, were ambivalent of Indonesian economic development, and spoke Portuguese amongst themselves, stressing their Portuguese heritage. Seeking help from Portugal for self-determination, they considered Indonesia an occupying force. Abroad, Fretilin's members—most notably former journalist José Ramos-Horta (later to be prime minister and president)—pushed their cause in diplomatic forums.

The reduced armed resistance prompted the Indonesian government in 1988 to open up East Timor to improve its commercial prospects, including a lifting of the travel ban on journalists. The new policy came from foreign minister Ali Alatas. Alatas and other diplomats swayed Suharto in favor of the policy as a response to international concerns despite concerns among the military leadership that it would lead to a loss of control. In late 1989, hardline military commander Brigadier General Mulyadi was replaced by Brigadier General Rudolph Warouw who promised a more "persuasive" approach to anti-integrationists. Restrictions on travel within the territory were reduced and groups of political prisoners were released. Warouw attempted to increase military discipline; in February 1990 an Indonesian soldier was prosecuted for unlawful conduct in East Timor, the first such action since the invasion.

The reduced fear of persecution encouraged the resistance movements; anti-integration protests accompanied high-profile visits to East Timor, including that of Pope John Paul II in 1989. Additionally, the end of the Cold War removed much of the justification for western support of Indonesia's occupation. The resulting increase in international attention to self-determination and human rights put further pressure on Indonesia. Subsequent events within East Timor in the 1990s helped to dramatically raise the international profile of East Timor, which in turn significantly boosted the momentum of the resistance groups.

Santa Cruz massacre

During a memorial mass on 12 November 1991 for a pro-independence youth shot by Indonesian troops, demonstrators among the 2,500-strong crowd unfurled the Fretilin flag and banners with pro-independence slogans and chanted boisterously but peacefully. Following a brief confrontation between Indonesian troops and protesters, 200 Indonesian soldiers opened fire on the crowd killing at least 250 Timorese.

The testimonies of foreigners at the cemetery were quickly reported to international news organisations, and video footage of the massacre was widely broadcast internationally, causing outrage. In response to the massacre, activists around the world organised in solidarity with the East Timorese, and a new urgency was brought to calls for self-determination. TAPOL, a British organisation formed in 1973 to advocate for democracy in Indonesia, increased its work around East Timor. In the United States, the East Timor Action Network (now the East Timor and Indonesia Action Network) was founded and soon had chapters in ten cities around the country. Other solidarity groups appeared in Portugal, Australia, Japan, Germany, Malaysia, Ireland, and Brazil. Coverage of the massacre was a vivid example of how the growth of new media in Indonesia was making it increasingly difficult for the "New Order" to control information flow in and out of Indonesia, and that in the post-Cold War 1990s, the government was coming under increasing international scrutiny. Several pro-democracy student groups and their magazines began to openly and critically discuss not just East Timor, but also the "New Order" and the broader history and future of Indonesia.

Sharp condemnation of the military came not just from the international community, but from within parts of the Indonesian elite. The massacre ended the governments 1989 opening of the territory and a new period of repression began. Warouw was removed from his position and his more accommodating approach to Timorese resistance rebuked by his superiors. Suspected Fretilin sympathisers were arrested, human rights abuses rose, and the ban on foreign journalists was reimposed. Hatred intensified amongst Timorese of the Indonesian military presence. Major General Prabowo's, Kopassus Group 3 trained militias gangs dressed in black hoods to crush the remaining resistance.

Arrest of Xanana Gusmão

On 20 November 1992, Fretilin leader Xanana Gusmão was arrested by Indonesian troops. In May 1993 he was sentenced to life imprisonment for "rebellion", but his sentence was later commuted to 20 years. The arrest of the universally acknowledged leader of the resistance was a major frustration to the anti-integration movement in East Timor, but Gusmão continued to serve as a symbol of hope from inside the Cipinang prison. Nonviolent resistance by East Timorese, meanwhile, continued to show itself. When President Bill Clinton visited Jakarta in 1994, twenty-nine East Timorese students occupied the US embassy to protest US support for Indonesia.

At the same time, human rights observers called attention to continued violations by Indonesian troops and police. A 1995 report by Human Rights Watch noted that "abuses in the territory continue to mount."

Nobel Peace Prize

In 1996 East Timor was suddenly brought to world attention when the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Bishop Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo and José Ramos-Horta "for their work towards a just and peaceful solution to the conflict in East Timor". The Nobel Committee indicated in its press release that it hoped the award would "spur efforts to find a diplomatic solution to the conflict in East Timor based on the people's right to self-determination". As Nobel scholar Irwin Abrams notes:

For Indonesia the prize was a great embarrassment.... In public statements the government tried to put distance between the two laureates, grudgingly recognising the prize for Bishop Belo, over whom it thought it could exercise some control, but accusing Ramos-Horta of responsibility for atrocities during the civil strife in East Timor and declaring that he was a political opportunist.

At the award ceremony Chairman Sejersted answered these charges, pointing out that during the civil conflict Ramos-Horta was not even in the country and on his return he tried to reconcile the two parties.

Diplomats from Indonesia and Portugal, meanwhile, continued the consultations required by the 1982 General Assembly resolution, in a series of meetings intended to resolve the problem of what Foreign Minister Ali Alatas called the "pebble in the Indonesian shoe".

End of Indonesian control

Renewed United Nations-brokered mediation efforts between Indonesia and Portugal began in early 1997.

Transition in Indonesia

Independence for East Timor, or even limited regional autonomy, was never going to be allowed under Suharto's New Order. Notwithstanding Indonesian public opinion in the 1990s occasionally showing begrudging appreciation of the Timorese position, it was widely feared that an independent East Timor would destabilise Indonesian unity. The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, however, caused tremendous upheaval in Indonesia and led to Suharto's resignation in May 1998, ending his thirty-year presidency. Prabowo, by then in command of the powerful Indonesian Strategic Reserve, went into exile in Jordan and military operations in East Timor were costing the bankrupt Indonesian government a million dollars a day. The subsequent "reformasi" period of relative political openness and transition, included an unprecedented debate about Indonesia's relationship with East Timor. For the remainder of 1998, discussion forums took place throughout Dili working towards a referendum. Foreign Minister Alatas, described plans for phased autonomy leading to possible independence as "all pain, no gain" for Indonesia. On 8 June 1998, three weeks after taking office, Suharto's successor B. J. Habibie announced that Indonesia would soon offer East Timor a special plan for autonomy.

In late 1998, the Australian government of John Howard drafted a letter to Indonesia advising of a change in Australian policy and advocating for the staging of a referendum on independence within a decade. President Habibie saw such an arrangement as implying "colonial rule" by Indonesia, and he decided to call a snap referendum on the issue.

Indonesia and Portugal announced on 5 May 1999 that it had agreed to hold a vote allowing the people of East Timor to choose between the autonomy plan or independence. The vote, to be administered by the United Nations Mission in East Timor (UNAMET), was initially scheduled for 8 August but later postponed until 30 August. Indonesia also took responsibility for security; this arrangement caused worry in East Timor, but many observers believe that Indonesia would have refused to allow foreign peacekeepers during the vote.

1999 referendum

As groups supporting autonomy and independence began campaigning, a series of pro-integration paramilitary groups of East Timorese began threatening violence—and indeed committing violence—around the country. Alleging pro-independence bias on the part of UNAMET, the groups were seen working with and receiving training from Indonesian soldiers. Before the May agreement was announced, an April paramilitary attack in Liquiça left dozens of East Timorese dead. On 16 May 1999, a gang accompanied by Indonesian troops attacked suspected independence activists in the village of Atara; in June another group attacked a UNAMET office in Maliana. Indonesian authorities claimed to be helpless to stop the violence between rival factions among the East Timorese, but Ramos-Horta joined many others in scoffing at such notions. In February 1999 he said: "Before [Indonesia] withdraws it wants to wreak major havoc and destabilization, as it has always promised. We have consistently heard that over the years from the Indonesian military in Timor."

As militia leaders warned of a "bloodbath", Indonesian "roving ambassador" Francisco Lopes da Cruz declared: "If people reject autonomy there is the possibility blood will flow in East Timor." One paramilitary announced that a vote for independence would result in a "sea of fire", an expression referring to the Bandung Sea of Fire during Indonesia's own war of independence from the Dutch. As the date of the vote drew near, reports of anti-independence violence continued to accumulate.

The day of the vote, 30 August 1999, was generally calm and orderly. 98.6% of registered voters cast ballots, and on 4 September UN secretary-general Kofi Annan announced that 78.5% of the votes had been cast for independence. Brought up on the "New Order"'s insistence that the East Timorese supported integration, Indonesians were either shocked by or disbelieved that the East Timorese had voted against being part of Indonesia. Many people accepted media stories blaming the supervising United Nations and Australia who had pressured Habibie for a resolution.

Within hours of the results, paramilitary groups had begun attacking people and setting fires around the capital Dili. Foreign journalists and election observers fled, and tens of thousands of East Timorese took to the mountains. Islamic gangs attacked Dili's Catholic diocese building, killing two dozen people; the next day, the headquarters of the ICRC was attacked and burned to the ground. Almost one hundred people were killed later in Suai, and reports of similar massacres poured in from around East Timor. The UN withdrew most of its personnel, but the Dili compound had been flooded with refugees. Four UN workers refused to evacuate unless the refugees were withdrawn as well, insisting they would rather die at the hands of the paramilitary groups. At the same time, Indonesian troops and paramilitary gangs forced over 200,000 people into West Timor, into camps described by Human Rights Watch as "deplorable conditions".

When a UN delegation arrived in Jakarta on 8 September, they were told by Indonesian president Habibie that reports of bloodshed in East Timor were "fantasies" and "lies". General Wiranto of the Indonesian military insisted that his soldiers had the situation under control, and later expressed his emotion for East Timor by singing the 1975 hit song "Feelings" at an event for military wives.

Indonesian withdrawal and peacekeeping force

The violence was met with widespread public anger in Australia, Portugal and elsewhere and activists in Portugal, Australia, the United States and other nations pressured their governments to take action. Australian prime minister John Howard consulted United Nations secretary-general Kofi Annan and lobbied US president Bill Clinton to support an Australian led international peacekeeper force to enter East Timor to end the violence. The United States offered crucial logistical and intelligence resources and an "over-horizon" deterrent presence but did not commit forces to the operation. Finally, on 11 September, Clinton announced:

I have made clear that my willingness to support future economic assistance from the international community will depend upon how Indonesia handles the situation from today.

Indonesia, in dire economic straits, relented. President BJ Habibie announced on 12 September that Indonesia would withdraw Indonesian soldiers and allow an Australian-led international peacekeeping force to enter East Timor.

On 15 September 1999, the United Nations Security Council expressed concern at the deteriorating situation in East Timor and issued UNSC Resolution 1264 calling for a multinational force to restore peace and security to East Timor, to protect and support the United Nations mission there, and to facilitate humanitarian assistance operations until such time as a United Nations peacekeeping force could be approved and deployed in the area.

The International Force for East Timor, or INTERFET, under the command of Australian Major General Peter Cosgrove, entered Dili on 20 September and by 31 October the last Indonesian troops had left East Timor. The arrival of thousands of international troops in East Timor caused the militia to flee across the border into Indonesia, whence sporadic cross-border raids by the militia against INTERFET forces were conducted.

The United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) was established at the end of October and administered the region for two years. Control of the nation was turned over to the government of East Timor, and independence was declared on 20 May 2002. On 27 September of the same year, East Timor joined the United Nations as its 191st member state.

The bulk of the military forces of INTERFET were Australian—more than 5,500 troops at its peak, including an infantry brigade, with armoured and aviation support—while eventually, 22 nations contributed to the force which at its height numbered over 11,000 troops. The United States provided crucial logistic and diplomatic support throughout the crisis. At the same time, the cruiser USS Mobile Bay protected the INTERFET naval fleet and a US Marine infantry battalion of 1,000 men—plus organic armour and artillery—was also stationed off the coast aboard the USS Belleau Wood to provide a strategic reserve in the event of significant armed opposition.

Consequences

Number of deaths

Precise estimates of the death toll are difficult to determine. The 2005 report of the UN's Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor (CAVR) reports an estimated minimum number of conflict-related deaths of 102,800 (+/- 12,000).

Indonesian governors of East Timor

- President of the Provisional Government:

- 17 December 1975 – 17 July 1976: Arnaldo dos Reis Araújo

- Governors:

- 1976 – 1978: Arnaldo dos Reis Araújo

- 1978 – 1982: Guilherme Maria Gonçalves

- 18 September 1982 – 18 September 1992: Mário Viegas Carrascalão

- 18 September 1992 – 25 October 1999: José Abílio Osório Soares

Depictions in fiction

- Balibo, a 2009 Australian film about the Balibo Five, a group of Australian journalists who were captured and killed just prior to the Indonesian invasion of East Timor. The Redundancy of Courage, a novel which was short-listed for the Booker Prize, by Timothy Mo, is generally accepted to be about East Timor.

See also

- Timor Timur