Indian removal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Indian removal |

|

|---|---|

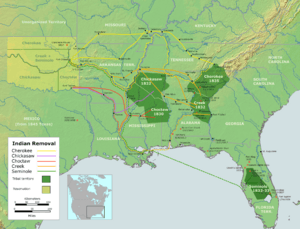

Routes of southern removals

|

|

| Location | United States |

| Date | 1830–1847 |

| Target | Native Americans in the eastern United States |

|

Attack type

|

Population transfer, ethnic cleansing, genocide |

| Deaths | 8,000+ (lowest estimate) |

| Assailants | United States |

| Motive | Expansionism |

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi River – specifically, to a designated Indian Territory (roughly, present-day Oklahoma). The Indian Removal Act, the key law which authorized the removal of Native tribes, was signed by Andrew Jackson in 1830. Although Jackson took a hard line on Indian removal, the law was enforced primarily during the Martin Van Buren administration. After the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1831, approximately 60,000 members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations (including thousands of their black slaves) were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands, with thousands dying during the Trail of Tears.

Indian removal, a popular policy among white settlers, was a consequence of actions by European settlers in North America during the colonial period and then by the United States government (and its citizens) until the mid-20th century. The policy traced its origins to the administration of James Monroe, although it addressed conflicts between European and Native Americans which had occurred since the 17th century and were escalating into the early 19th century (as white settlers pushed westward in the cultural belief of manifest destiny). Historical views of Indian removal have been reevaluated since that time. Widespread contemporary acceptance of the policy, due in part to the popular embrace of the concept of manifest destiny, has given way to a more somber perspective. Historians have often described the removal of Native Americans as paternalism, ethnic cleansing, or genocide.

Contents

Revolutionary background

American leaders in the Revolutionary and early US eras debated about whether Native Americans should be treated as individuals or as nations.

Declaration of Independence

In the indictment section of the Declaration of Independence, the Indigenous inhabitants of the United States are referred to as "merciless Indian Savages", reflecting a commonly held view at the time by white people in the United States.

Benjamin Franklin

In a draft "Proposed Articles of Confederation" presented to the Continental Congress on May 10, 1775, Benjamin Franklin called for a "perpetual Alliance" with the Indians in the nation about to be born, particularly with the six nations of the Iroquois Confederacy:

Article XI. A perpetual alliance offensive and defensive is to be entered into as soon as may be with the Six Nations; their Limits to be ascertained and secured to them; their Land not to be encroached on, nor any private or Colony Purchases made of them hereafter to be held good, nor any Contract for Lands to be made but between the Great Council of the Indians at Onondaga and the General Congress. The Boundaries and Lands of all the other Indians shall also be ascertained and secured to them in the same manner; and Persons appointed to reside among them in proper Districts, who shall take care to prevent Injustice in the Trade with them, and be enabled at our general Expense by occasional small Supplies, to relieve their personal Wants and Distresses. And all Purchases from them shall be by the Congress for the General Advantage and Benefit of the United Colonies.

Early congressional acts

The Confederation Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 (a precedent for U.S. territorial expansion would occur for years to come), calling for the protection of Native American "property, rights, and liberty"; the U.S. Constitution of 1787 (Article I, Section 8) made Congress responsible for regulating commerce with the Indian tribes. In 1790, the new U.S. Congress passed the Indian Nonintercourse Act (renewed and amended in 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834) to protect and codify the land rights of recognized tribes.

George Washington

President George Washington, in his 1790 address to the Seneca Nation which called the pre-Constitutional Indian land-sale difficulties "evils", said that the case was now altered and pledged to uphold Native American "just rights". In March and April 1792, Washington met with 50 tribal chiefs in Philadelphia—including the Iroquois—to discuss strengthening the friendship between them and the United States. Later that year, in his fourth annual message to Congress, Washington stressed the need to build peace, trust, and commerce with Native Americans:

I cannot dismiss the subject of Indian affairs without again recommending to your consideration the expediency of more adequate provision for giving energy to the laws throughout our interior frontier, and for restraining the commission of outrages upon the Indians; without which all pacific plans must prove nugatory. To enable, by competent rewards, the employment of qualified and trusty persons to reside among them, as agents, would also contribute to the preservation of peace and good neighbourhood. If, in addition to these expedients, an eligible plan could be devised for promoting civilization among the friendly tribes, and for carrying on trade with them, upon a scale equal to their wants, and under regulations calculated to protect them from imposition and extortion, its influence in cementing their interests with our's [sic] could not but be considerable.

In his seventh annual message to Congress in 1795, Washington intimated that if the U.S. government wanted peace with the Indians it must behave peacefully; if the U.S. wanted raids by Indians to stop, raids by American "frontier inhabitants" must also stop.

Thomas Jefferson

In his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), Thomas Jefferson defended Native American culture and marvelled at how the tribes of Virginia "never submitted themselves to any laws, any coercive power, any shadow of government" due to their "moral sense of right and wrong". He wrote to the Marquis de Chastellux later that year, "I believe the Indian then to be in body and mind equal to the whiteman". Jefferson's desire, as interpreted by Francis Paul Prucha, was for Native Americans to intermix with European Americans and become one people. To achieve that end as president, Jefferson offered U.S. citizenship to some Indian nations and proposed offering them credit to facilitate trade.

On 27 February 1803, Jefferson wrote in a letter to William Henry Harrison:

In this way our settlements will gradually circumbscribe & approach the Indians, & they will in time either incorporate with us as citizens of the US. or remove beyond the Missisipi. The former is certainly the termination of their history most happy for themselves. But in the whole course of this, it is essential to cultivate their love. As to their fear, we presume that our strength & their weakness is now so visible that they must see we have only to shut our hand to crush them, & that all our liberalities to them proceed from motives of pure humanity only.

Jeffersonian policy

As president, Thomas Jefferson developed a far-reaching Indian policy with two primary goals. He wanted to assure that the Native nations (not foreign nations) were tightly bound to the new United States, as he considered the security of the nation to be paramount. He also wanted to "civilize" them into adopting an agricultural, rather than a hunter-gatherer, lifestyle. These goals would be achieved through treaties and the development of trade.

Jefferson initially promoted an American policy which encouraged Native Americans to become assimilated, or "civilized". He made sustained efforts to win the friendship and cooperation of many Native American tribes as president, repeatedly articulating his desire for a united nation of whites and Indians as in his November 3, 1802, letter to Seneca spiritual leader Handsome Lake:

Go on then, brother, in the great reformation you have undertaken ... In all your enterprises for the good of your people, you may count with confidence on the aid and protection of the United States, and on the sincerity and zeal with which I am myself animated in the furthering of this humane work. You are our brethren of the same land; we wish your prosperity as brethren should do. Farewell.

When a delegation from the Cherokee Nation's Upper Towns lobbied Jefferson for the full and equal citizenship promised to Indians living in American territory by George Washington, his response indicated that he was willing to grant citizenship to those Indian nations who sought it. In his eighth annual message to Congress on November 8, 1808, he presented a vision of white and Indian unity:

With our Indian neighbors the public peace has been steadily maintained ... And, generally, from a conviction that we consider them as part of ourselves, and cherish with sincerity their rights and interests, the attachment of the Indian tribes is gaining strength daily... and will amply requite us for the justice and friendship practiced towards them ... [O]ne of the two great divisions of the Cherokee nation have now under consideration to solicit the citizenship of the United States, and to be identified with us in-laws and government, in such progressive manner as we shall think best.

As some of Jefferson's other writings illustrate, however, he was ambivalent about Indian assimilation and used the words "exterminate" and "extirpate" about tribes who resisted American expansion and were willing to fight for their lands. Jefferson intended to change Indian lifestyles from hunting and gathering to farming, largely through "the decrease of game rendering their subsistence by hunting insufficient". He expected the change to agriculture to make them dependent on white Americans for goods, and more likely to surrender their land or allow themselves to be moved west of the Mississippi River. In an 1803 letter to William Henry Harrison, Jefferson wrote:

Should any tribe be foolhardy enough to take up the hatchet at any time, the seizing the whole country of that tribe, and driving them across the Mississippi, as the only condition of peace, would be an example to others, and a furtherance of our final consolidation.

In that letter, Jefferson spoke about protecting the Indians from injustices perpetrated by whites:

Our system is to live in perpetual peace with the Indians, to cultivate an affectionate attachment from them, by everything just and liberal which we can do for them within ... reason, and by giving them effectual protection against wrongs from our own people.

According to the treaty of February 27, 1819, the U.S. government would offer citizenship and 640 acres (260 ha) of land per family to Cherokees who lived east of the Mississippi. Native American land was sometimes purchased, by treaty or under duress. The idea of land exchange, that Native Americans would give up their land east of the Mississippi in exchange for a similar amount of territory west of the river, was first proposed by Jefferson in 1803 and first incorporated into treaties in 1817 (years after the Jefferson presidency). The Indian Removal Act of 1830 included this concept.

John C. Calhoun's plan

Under President James Monroe, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun devised the first plans for Indian removal. Monroe approved Calhoun's plans by late 1824 and, in a special message to the Senate on January 27, 1825, requested the creation of the Arkansaw and Indian Territories; the Indians east of the Mississippi would voluntarily exchange their lands for lands west of the river. The Senate accepted Monroe's request, and asked Calhoun to draft a bill which was killed in the House of Representatives by the Georgia delegation. President John Quincy Adams assumed the Calhoun–Monroe policy, and was determined to remove the Indians by non-forceful means; Georgia refused to consent to Adams' request, forcing the president to forge a treaty with the Cherokees granting Georgia the Cherokee lands. On July 26, 1827, the Cherokee Nation adopted a written constitution (modeled on that of the United States) which declared that they were an independent nation with jurisdiction over their own lands. Georgia contended that it would not countenance a sovereign state within its own territory, and asserted its authority over Cherokee territory. When Andrew Jackson became president as the candidate of the newly-organized Democratic Party, he agreed that the Indians should be forced to exchange their eastern lands for western lands (including relocation) and vigorously enforced Indian removal.

Opposition to removal from U.S. citizens

Although Indian removal was a popular policy, it was also opposed on legal and moral grounds; it also ran counter to the formal, customary diplomatic interaction between the federal government and the Native nations. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote the widely-published letter "A Protest Against the Removal of the Cherokee Indians from the State of Georgia" in 1838, shortly before the Cherokee removal. Emerson criticizes the government and its removal policy, saying that the removal treaty was illegitimate; it was a "sham treaty", which the U.S. government should not uphold. He describes removal as

such a dereliction of all faith and virtues, such a denial of justice…in the dealing of a nation with its own allies and wards since the earth was made…a general expression of despondency, of disbelief, that any goodwill accrues from a remonstrance on an act of fraud ad robbery, appeared in those men to whom we naturally turn for aid and counsel.

Emerson concludes his letter by saying that it should not be a political issue, urging President Martin Van Buren to prevent the enforcement of Cherokee removal. Other people and social organizations throughout the country also opposed removal.

Native American response to removal

Native groups reshaped their governments, made constitutions and legal codes, and sent delegates to Washington to negotiate policies and treaties to uphold their autonomy and ensure federally-promised protection from white states. They thought that acclimating, as the U.S. wanted them to, would stem removal policy and create a better relationship with the federal government and surrounding states.

Native American nations had differing views about removal. Although most wanted to remain on their native lands and do anything possible to ensure that, others believed that removal to a nonwhite area was their only option to maintain their autonomy and culture. The U.S. used this division to forge removal treaties with (often) minority groups who became convinced that removal was the best option for their people. These treaties were often not acknowledged by most of a nation's people. When Congress ratified the removal treaty, the federal government could use military force to remove Native nations if they had moved (or had begun moving) by the date stipulated in the treaty.

Indian Removal Act

When Andrew Jackson became president of the United States in 1829, his government took a hard line on Indian removal; Jackson abandoned his predecessors' policy of treating Indian tribes as separate nations, aggressively pursuing all Indians east of the Mississippi who claimed constitutional sovereignty and independence from state laws. They were to be removed to reservations in Indian Territory, west of the Mississippi (present-day Oklahoma), where they could exist without state interference. At Jackson's request, Congress began a debate on an Indian-removal bill. After fierce disagreement, the Senate passed the bill by a 28–19 vote; the House had narrowly passed it, 102–97. Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law on May 30, 1830.

That year, most of the Five Civilized Tribes—the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, and Cherokee—lived east of the Mississippi. The Indian Removal Act implemented federal-government policy towards its Indian populations, moving Native American tribes east of the Mississippi to lands west of the river. Although the act did not authorize the forced removal of indigenous tribes, it enabled the president to negotiate land-exchange treaties.

Choctaw

On September 27, 1830, the Choctaw signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek and became the first Native American tribe to be removed. The agreement was one of the largest transfers of land between the U.S. government and Native Americans which was not the result of war. The Choctaw signed away their remaining traditional homelands, opening them up for European-American settlement in Mississippi Territory. When the tribe reached Little Rock, a chief called its trek a "trail of tears and death".

In 1831, French historian and political scientist Alexis de Tocqueville witnessed an exhausted group of Choctaw men, women and children emerging from the forest during an exceptionally cold winter near Memphis, Tennessee, on their way to the Mississippi to be loaded onto a steamboat. He wrote,

In the whole scene there was an air of ruin and destruction, something which betrayed a final and irrevocable adieu; one couldn't watch without feeling one's heart wrung. The Indians were tranquil but sombre and taciturn. There was one who could speak English and of whom I asked why the Chactas were leaving their country. "To be free," he answered, could never get any other reason out of him. We ... watch the expulsion ... of one of the most celebrated and ancient American peoples.

Cherokee

While the Indian Removal Act made the move of the tribes voluntary, it was often abused by government officials. The best-known example is the Treaty of New Echota, which was signed by a small faction of twenty Cherokee tribal members (not the tribal leadership) on December 29, 1835. Most of the Cherokee later blamed the faction and the treaty for the tribe's forced relocation in 1838. An estimated 4,000 Cherokee died in the march, which is known as the Trail of Tears. Missionary organizer Jeremiah Evarts urged the Cherokee Nation to take its case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Marshall court heard the case in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), but declined to rule on its merits; the court declaring that the Native American tribes were not sovereign nations, and could not "maintain an action" in U.S. courts. In an opinion written by Chief Justice Marshall in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), individual states had no authority in American Indian affairs.

The state of Georgia defied the Supreme Court ruling, and the desire of white settlers and land speculators for Indian lands continued unabated; some whites claimed that Indians threatened peace and security. The Georgia legislature passed a law forbidding whites from living on Indian territory after March 31, 1831, without a license from the state; this excluded white missionaries who opposed Indian removal.

Seminole

The Seminole refused to leave their Florida lands in 1835, leading to the Second Seminole War. Osceola was a Seminole leader of the people's fight against removal. Based in the Everglades, Osceola and his band used surprise attacks to defeat the U.S. Army in a number of battles. In 1837, Osceola was duplicitously captured by order of U.S. General Thomas Jesup when Osceola came under a flag of truce to negotiate peace near Fort Peyton. Osceola died in prison of illness; the war resulted in over 1,500 U.S. deaths, and cost the government $20 million. Some Seminole traveled deeper into the Everglades, and others moved west. The removal continued, and a number of wars broke out over land.

Muskogee (Creek)

In the aftermath of the Treaties of Fort Jackson and the Washington, the Muscogee were confined to a small strip of land in present-day east central Alabama. The Creek national council signed the Treaty of Cusseta in 1832, ceding their remaining lands east of the Mississippi to the U.S. and accepting relocation to the Indian Territory. Most Muscogee were removed to the territory during the Trail of Tears in 1834, although some remained behind. Although the Creek War of 1836 ended government attempts to convince the Creek population to leave voluntarily, Creeks who had not participated in the war were not forced west (as others were). The Creek population was placed into camps and told that they would be relocated soon. Many Creek leaders were surprised by the quick departure, but could do little to challenge it. The 16,000 Creeks were organized into five detachments who were to be sent to Fort Gibson. The Creek leaders did their best to negotiate better conditions, and succeeded in obtaining wagons and medicine. To prepare for the relocation, Creeks began to deconstruct their spiritual lives; they burned piles of lightwood over their ancestors' graves to honor their memories, and polished the sacred plates which would travel at the front of each group. They also prepared financially, selling what they could not bring. Many were swindled by local merchants out of valuable possessions (including land), and the military had to intervene. The detachments began moving west in September 1836, facing harsh conditions. Despite their preparations, the detachments faced bad roads, worse weather, and a lack of drinkable water. When all five detachments reached their destination, they recorded their death toll. The first detachment, with 2,318 Creeks, had 78 deaths; the second had 3,095 Creeks, with 37 deaths. The third had 2,818 Creeks, and 12 deaths; the fourth, 2,330 Creeks and 36 deaths. The fifth detachment, with 2,087 Creeks, had 25 deaths.

Friends and Brothers – By permission of the Great Spirit above, and the voice of the people, I have been made President of the United States, and now speak to you as your Father and friend, and request you to listen. Your warriors have known me long. You know I love my white and red children, and always speak with a straight, and not with a forked tongue; that I have always told you the truth ... Where you now are, you and my white children are too near to each other to live in harmony and peace. Your game is destroyed, and many of your people will not work and till the earth. Beyond the great River Mississippi, where a part of your nation has gone, your Father has provided a country large enough for all of you, and he advises you to remove to it. There your white brothers will not trouble you; they will have no claim to the land, and you can live upon it you and all your children, as long as the grass grows or the water runs, in peace and plenty. It will be yours forever. For the improvements in the country where you now live, and for all the stock which you cannot take with you, your Father will pay you a fair price ...

Chickasaw

Unlike other tribes, who exchanged lands, the Chickasaw were to receive financial compensation of $3 million from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River. They reached an agreement to purchase of land from the previously-removed Choctaw in 1836 after a bitter five-year debate, paying the Chocktaw $530,000 for the westernmost Choctaw land. Most of the Chickasaw moved in 1837 and 1838. The $3 million owed to the Chickasaw by the U.S. went unpaid for nearly 30 years.

Aftermath

The Five Civilized Tribes were resettled in the new Indian Territory. The Cherokee occupied the northeast corner of the territory and a 70-mile-wide (110 km) strip of land in Kansas on its border with the territory. Some indigenous nations resisted the forced migration more strongly. The few who stayed behind eventually formed tribal groups, including the Eastern Band of Cherokee (based in North Carolina), the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, and the Creeks in Alabama (including the Poarch Band).

Removals

North

Tribes in the Old Northwest were smaller and more fragmented than the Five Civilized Tribes, so the treaty and emigration process was more piecemeal. Following the Northwest Indian War, most of the modern state of Ohio was taken from native nations in the 1795 Treaty of Greenville. Tribes such as the already-displaced Lenape (Delaware tribe), Kickapoo and Shawnee, were removed from Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio during the 1820s. The Potawatomi were forced out of Wisconsin and Michigan in late 1838, and were resettled in Kansas Territory. Communities remaining in present-day Ohio were forced to move to Louisiana, which was then controlled by Spain.

Bands of Shawnee, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Sauk, and Meskwaki (Fox) signed treaties and relocated to the Indian Territory. In 1832, the Sauk leader Black Hawk led a band of Sauk and Fox back to their lands in Illinois; the U.S. Army and Illinois militia defeated Black Hawk and his warriors in the Black Hawk War, and the Sauk and Fox were relocated to present-day Iowa. The Miami were split, with many of the tribe resettled west of the Mississippi River during the 1840s.

In the Second Treaty of Buffalo Creek (1838), the Senecas transferred all their land in New York (except for one small reservation) in exchange for 200,000 acres (810 km2) of land in Indian Territory. The federal government would be responsible for the removal of the Senecas who opted to go west, and the Ogden Land Company would acquire their New York lands. The lands were sold by government officials, however, and the proceeds were deposited in the U.S. Treasury. Maris Bryant Pierce, a "young chief" served as a lawyer representing four territories of the Seneca tribe, starting in 1838. The Senecas asserted that they had been defrauded, and sued for redress in the Court of Claims. The case was not resolved until 1898, when the United States awarded $1,998,714.46 in compensation to "the New York Indians". The U.S. signed treaties with the Senecas and the Tonawanda Senecas in 1842 and 1857, respectively. Under the treaty of 1857, the Tonawandas renounced all claim to lands west of the Mississippi in exchange for the right to buy back the Tonawanda Reservation from the Ogden Land Company. Over a century later, the Senecas purchased a 9-acre (3.6 ha) plot (part of their original reservation) in downtown Buffalo.

South

| Nation | Population before removal | Treaty and year | Major emigration | Total removed | Number remaining | Deaths during removal | Deaths from warfare |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choctaw | 19,554 + White citizens of the Choctaw Nation + 500 Black slaves | Dancing Rabbit Creek (1830) | 1831–1836 | 15,000 | 5,000–6,000 | 2,000–4,000+ (cholera) | none |

| Creek (Muscogee) | 22,700 + 900 Black slaves | Cusseta (1832) | 1834–1837 | 19,600 | Several hundred | 3,500 (disease after removal) | Unknown (Creek War of 1836) |

| Chickasaw | 4,914 + 1,156 Black slaves | Pontotoc Creek (1832) | 1837–1847 | over 4,000 | Several hundred | 500–800 | none |

| Cherokee | 16,542 + 201 married White + 1,592 Black slaves | New Echota (1835) | 1836–1838 | 16,000 | 1,500 | 2,000–4,000 | none |

| Seminole | 3,700–5,000 + fugitive slaves | Payne's Landing (1832) | 1832–1842 | 2,833–4,000 | 250–500 | 700 (Second Seminole War) |

Changed perspective

Historical views of Indian removal have been reevaluated since that time. Widespread contemporary acceptance of the policy, due in part to the popular embrace of the concept of manifest destiny, has given way to a more-somber perspective. The removals have been described by historians to paternalism, ethnic cleansing, or genocide. Historian David Stannard has called it genocide.

Jackson's reputation

Andrew Jackson's reputation has been negatively affected by his treatment of the Indians. Historians who admire Jackson's strong presidential leadership, such as Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., would gloss over the Indian Removal in a footnote. In 1969, Francis Paul Prucha wrote that Jackson's removal of the Five Civilized Tribes from the hostile white environment of the Old South to Oklahoma probably saved them. Jackson was sharply attacked by political scientist Michael Rogin and historian Howard Zinn during the 1970s, primarily on this issue; Zinn called him an "exterminator of Indians". According to historians Paul R. Bartrop and Steven L. Jacobs, however, Jackson's policies do not meet the criteria for physical or cultural genocide.

See also

In Spanish: Deportación de los indios de los Estados Unidos para niños

In Spanish: Deportación de los indios de los Estados Unidos para niños