Ignacio Baleztena Ascárate facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ignacio Baleztena Ascárate

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Ignacio Baleztena Ascárate

1 April 1887 Pamplona, Spain

|

| Died | 2 September 1972 (aged 85) Pamplona, Spain

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | self-government official |

| Known for | Pamplona icon |

| Political party | Traditionalist Communion |

Ignacio Baleztena Ascárate (1887–1972) was a Spanish folk customs expert, a Carlist politician and soldier.

Contents

Family and youth

Ignacio's paternal grandfather, José Joaquín Baleztena Echeverría, a native of Navarrese Leitza, tried his luck in California and Cuba before returning to the home town, where he owned two buildings next to Ayuntamiento. His son and Ignacio's father, Joaquín Baleztena Muñagorri, formed part of new Navarrese economic and political elites. Holding a number of rural properties in the comarca of Valles Meridionales, he was co-founder of Conducción de Aguas de Arteta and shareholder of a number of other local companies. Elected consejal of Pamplona in the 1880s and 1890s, he served as vicepresident of the local Circulo Carlista. Ignacio's mother, María Dolores Ascárate Echeverría, was descendant to a Carlist family; her father served as officer under Carlos V during the First Carlist War.

Ignacio was born after the family had moved from Leitza to Pamplona. He received secondary education in the Piarist Colegio de los Escolapios and was raised, like his 8 siblings, in the fervently Catholic ambience. His older sister, María Isabel, was initially supposed to marry Juan Vázquez de Mella. His older brother, Joaquín, became the Carlist political leader in Navarre. His paternal cousins Arraiza Baleztena sympathised with Carlism and held different posts in the Pamplona ayuntamiento early 20th century. His younger sister Dolores was a Carlist activist and author. His younger brother, Pedro María Baleztena Ascarate, became a famous pelota player.

Married (1927) to Carmen Abarrategui Gorosábel, Ignacio fathered 10 children. Joaquín (Joaquíncho) was active in El Pensamiento Navarro; Javier was director of Archivo General de Navarra and is author of historical and historiographical works related to the province, while Cruz Maria directed B-class movies. Most of the family remained Carlist, some of them engaged in politics. A few of his grandchildren became public figures; Ignacio Baleztena Navarrete represents Navarre at the EU headquarters in Brussels, Joaquin Baleztena Gurrea is a well known Pamplona physician while Carola Baleztena is a TV starlet and gossip media celebrity.

Early public activity

Allegedly already as a child Ignacio took part in street protests against Gamazada in the 1890s. He commenced his lifetime career as a youngster, co-organising and shaping various village feasts – especially the local santiburcios – in Leitza; in the family house he set up an amateur theatre, where he directed and performed along friends and relatives, staging also his own juvenile plays. He commenced studying law in the Jesuit Deusto college in Bilbao, but left to study architecture in Madrid and to continue with law in Salamanca; during his academic years Baleztena continued with cultural activities writing short stories and couplets, first for friends and than for public. Contributing with short pieces to various periodicals, during the Salamanca years he set up his own, El Bólido. He completed his first academic curriculum in 1910, returning to Pamplona somewhat earlier. Became engaged in a number of Catholic initiatives aimed against Ley del Candado, the most momentous having been the huge 1908 Gipuzkoan gathering known as acto de Zumárraga. The event was heavily influenced by the Carlists; as part of their preparations Baleztena wrote Spanish lyrics of a traditional Carlist anthem "Oriamendi", originally sung only in Basque. Also in 1908 he set up El Requeté de Pamplona, a periodical intended for Carlist youth. In 1911 he was elected president of Juventud Jaimista in Pamplona, though his leadership style was peculiar, with special focus on zarzuelas, balls, juegos florales, historical re-enactments, spectacles and other carnivalesque performance genres. In 1914, having graduated in law from Salamanca, he was offered the job of personal secretary by his brother-in-law, the Spanish consul in Pau. Ignacio remained in the Spanish consular service in France until 1918.

Public servant

In 1918 Baleztena joined the Carlist-foralist list of candidates in the local elections; successful, he became concejal of the Pamplona Ayuntamiento. One of his first initiatives was to create Caja de Ahorros de Navarra, an institution run by the Diputación Foral and providing popular affordable credit. He made his name as a staunch advocate of traditional local legal establishments. During initial works on vasco-navarrese autonomy he co-founded Comité pro Autonomía and co-signed a proclamation, issued by Junta Gestora de la Juventud pro Navarra, demanding restoration of traditional Navarrese foral regulations. In 1921 he represented the Jaimistas in Alianza Foral coalition and was elected to the Navarrese Diputación Foral. Re-elected in 1923 and 1926, he retained the post until 1928. Since 1925 he took part in talks between Diputación Foral and Ministerio de la Gobernación, though he demonstrated some flexibility when negotiating changes to the foral regime; in 1930 he formed part of the appointed Comisión Gestora. Baleztena kept endorsing a Navarrese identity also by other means, be it religious (San Francisco Javier commemorations), historical (unveiling of the monument to Navarrese heroes in Maya) or scientific (opening a Navarrese section in Museum of Bayonne).

Baleztena was vital to development and re-organisation of Archivo General de Navarra, the place where he spent more and more time as researcher starting late 1920s and which turned into his primary employment in the 1930s, when he was discharged from most other duties. In 1928 nominated the municipal Delegado de Turismo, resuming the function in the 1940s as Secretario del Comité Provincial de Turismo. In 1940 he founded Museo de Recuerdos Históricos in Pamplona, intended as Carlist cultural outpost; he was managing it as a director until the museum shut down in the mid-1960s. Since 1949 he was director of Museos de Navarra. Active in a number of mostly culture-related municipal and provincial bodies, like Comisión de Monumentos or Instituto Principe de Viana. By the end of his life he became an iconic and proverbial Pamplona figure, dubbed "aitacho".

Man of feasts

Since early youth Baleztena demonstrated particular interest in everything related to Giants and Bigheads; he was engaged in design, construction and carrying the figures. He later became an expert on gigantes, investigating their history and related rituals down to minuscule details. His interests gradually broadened to all Pamplonese feasts; in the 1920s he emerged as their key organizer and expert, publishing a number of related works and incalculable newspaper pieces. His contribution soon went far beyond cultivating local customs, as Baleztena was also reconstructing old-forgotten rituals and inventing new ones, incorporating them into celebrations of Epiphany, Holy Week or Corpus Christi; he launched also stand-alone customs like Procesión de San Saturnino. His activities went beyond Pamplona, as he revitalised local romerias, like the one to Ujué. All feasts contained a strong if not vital religious component, like the massive 1922 celebrations commemorating San Francisco Javier, styled as "arquetipo navarro. Some were strongly flavoured by Carlism, like the annual pilgrimage to Javier, launched in 1939.

Baleztena remained particularly fascinated by the sanfermines, investigating their history and forming part of Corte de San Fermín. He is credited for launching an unofficial feast anthem Uno de enero, dos de febrero and a popular Iruña-ko mezetak song, apart from a number of other unrelated chants. It was Baleztena and his friends who in 1911 first performed riau-riau; it remains debated whather the ritual was intended as a Carlist demonstration or simply as a juvenile joke. When it comes to running of the bulls he was in favor of as few regulations as possible, though none of the sources consulted mentions Baleztena running with the bulls himself. He remained one of key figures shaping sanfermines until the early 1960s, when he lost his grip on the event. The 1963-4 feasts were snatched by young Carlist progressists, who formatted them as their own political manifestations.

Baleztena's interest in feasts and customs is peculiar as it combined three different approaches: this of a scientist (anthropologist, historian, ethnographer, who pursues impartial scholarly studies), this of a politician (who shapes popular customs as vehicles of propagating own set of values), and this of a participant (who genuinely enjoys the feasts, contributes to them and takes part in them). Some scholars classify his approach as "costumbrismo nostálgico", which exalted religiosity and viewed modernising changes with anxiety. Some consider it a strategy of disseminating authoritarian discourse, which by means of cultural identification mobilised the society along conservative lines, a process similar to those employed by the Nazis in the Weimar Republic. Some present it as means of maintaining traditional Navarrese identity.

Vascólogo and Vascófilo

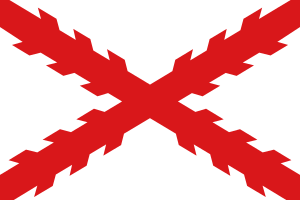

Baleztena's mothertongue was Spanish; he spoke Basque with some difficulty, though he understood Basque very well. Due to his childhood spent in Leitza, he was well accustomed and indeed fascinated by the Basque culture. Faced with the new phenomenon of Basque national drive, he opposed it with traditional vision of Basque identity; to this end, in 1913 he founded a Joshe Miguel weekly, intended as a Basque "antieuzkadiano" periodical. Baleztena early joined Sociedad de Estudios Vascos and formed part of its Junta Permanente; he participated in attempts to open Universidad Vasco-Navarra and remained active in Congresos de Estudios Vascos throughout the 1920s, promoting traditionalist Euskalerria against the nationalist Euzkadi. Baleztena opposed the usage of ikurriña as contrived and championed traditional provincial flags instead; he criticised newly invented feasts like Aberri Eguna, especially the 4th one staged in Pamplona.

In 1925 Baleztena co-founded Euskeraren Adiskideak, a society promoting Basque culture in Navarre. In 1931 he set up Záldiko Máldiko, a semi-private group focusing on folk dances and performing on festivals across Spanish and French Navarre. The grouping was re-formatted in 1934 as a Basque cultural folk association named Muthiko Alaiak, specialising in dance and theatric performances. Dominated by Carlists, Muthiko functioned as a vehicle for promoting Traditionalist vision of Navarrese society, though Baleztena did not refrain from mocking authorities (first Republican and later Francoist), especially by means of kurriños, performed often during local Carlist political events. After the Civil War Muthiko was considered the centre of antifrancoist Carlism. The group occasionally took part in official events, but it was registered as late as in 1949 and following continuous harassment, was re-opened in 1954. Though the last floor of the Baleztena house served as a stage for rehearsals, over time Baleztena lost control over Muthiko. As early as 1956 the communist intelligence considered the group a potentially promising area and indeed, in the 1960s it became a nucleus of socialism, which it remains until today, actively promoting also the Basque nationalism.

Politician

Since early youth Baleztena was active in juvenile Jaimist organisations. In 1919 he took part in Magna Junta Carlista de Biarritz and set up a new Carlist weekly Radica, representing the movement first in the Pamplona ayuntamiento and in the 1920s in the Deputación Foral. He considered taking part in "controlled" elections, planned by Berenguer in 1930. During first months of the Republic he forged a Carlist-nationalist alliance prior to the 1931 elections and engaged in works on vasco-navarrese autonomy. Initially in favour, he withdrew his support when governmental draft moved religious issues from autonomous to central portfolio. Member of the regional Carlist authorities, he got the family Pamplona house set ablaze by the leftist hit-squad in 1932. In 1933 he briefly headed the Navarrese Requeté.

In the spring of 1936 Baleztena negotiated Carlist support with Mola, within Carlism forming the faction pressing unconditional Carlist adherence to the coup. Upon the outbreak of hostilities the Baleztena houses turned into important insurgent centres. Ignacio helped to organise Tercio de San Miguel; in the mayhem that followed he is noted for saving Leftist supporters and POWs. Late July he volunteered to Tercio María de las Nieves battalion and served in Aragón, later on transferred to Tercio de Cristo Rey, deployed on the Madrid front and serving until the end of the war on the on-and-off basis. His stance towards unification is highly unclear, though it soon evolved into opposition; contesting Carlist amalgamation into Movimiento, he brusquely rejected Franco's blandishments. During the Second World War the Baleztenas helped the French refugees and demonstrated anti-Axis sympathies. They are usually considered members of the intransigent "bando falcondista", though Ignacio made also some conciliatory gestures towards Francoism. In the late 1940s the Baleztena brothers strived to rebuild clandestine or semi-official Carlist structures, both counted among Navarrese Carlist leaders. In 1952 Ignacio engineered one of the most humiliating snubs that Franco had to take. As late as 1954 he occasionally went into hiding, having been easy target of Falangist vengeance.

The Baleztenas voiced against a union with Juanistas, which did not necessarily amount to endorsing Don Javier's claim to the throne. In the mid-1950s they criticised Fal Conde as too conciliatory towards Francoism. Some scholars claim that they engineered a plot to remove Fal, though his actual dismissal and new course adopted by Carlism suited the competing "unionistas" faction more. When the Huguistas appeared on the scene in the late 1950s, the Baleztenas seemed rather skeptical. Though they lent some support to Carlos Hugo and maintained cordial relations with the Carlist claimant Don Javier until the late 1960s, they confronted the progressives when power struggle erupted within Carlism in the mid-1960s. The last success of the Baleztenas was regaining control over El Pensamiento Navarro in 1970, a short-lived victory as early 1970s Ignacio was expulsed from the socialist-dominated Partido Carlista.

See also

In Spanish: Ignacio Baleztena para niños

In Spanish: Ignacio Baleztena para niños

- Carlism

- Joaquín Baleztena Ascárate

- Basque nationalism

- Pamplona

- Leitza

- Festivale of San Fermín

- Gigantes y cabezudos

- romeria

- Marcha de Oriamendi