Idries Shah facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Idries Shah

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Idries Shah 16 June 1924 Simla, Punjab Province (British India) |

| Died | 23 November 1996 (aged 72) London, England, UK |

| Pen name | Arkon Daraul |

| Occupation | Writer, publisher |

| Genre | Eastern philosophy and culture |

| Subject | Sufism, psychology |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards | Outstanding Book of the Year (BBC "The Critics"), twice; six first prizes at the UNESCO World Book Year in 1973 |

| Spouse | Cynthia (Kashfi) Kabraji |

| Children | Saira Shah, Tahir Shah, Safia Shah |

| Signature | |

|

|

Idries Shah (/ˈɪdrɪs ˈʃɑː/; Hindi: इदरीस शाह, Pashto: ادريس شاه, Urdu: ادریس شاه; 16 June 1924 – 23 November 1996), also known as Idris Shah, Indries Shah, né Sayed Idries el-Hashimi (Arabic: سيد إدريس هاشمي) and by the pen name Arkon Daraul, was an Afghan author, thinker and teacher in the Sufi tradition. Shah wrote over three dozen books on topics ranging from psychology and spirituality to travelogues and culture studies.

Born in British India, the descendant of a family of Afghan nobles on his father's side and a Scottish mother, Shah grew up mainly in England. His early writings centred on magic and witchcraft. In 1960 he established a publishing house, Octagon Press, producing translations of Sufi classics as well as titles of his own. His seminal work was The Sufis, which appeared in 1964 and was well received internationally. In 1965, Shah founded the Institute for Cultural Research, a London-based educational charity devoted to the study of human behaviour and culture. A similar organisation, the Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge (ISHK), was established in the United States under the directorship of Stanford University psychology professor Robert Ornstein, whom Shah appointed as his deputy in the U.S.

In his writings, Shah presented Sufism as a universal form of wisdom that predated Islam. Emphasizing that Sufism was not static but always adapted itself to the current time, place and people, he framed his teaching in Western psychological terms. Shah made extensive use of traditional teaching stories and parables, texts that contained multiple layers of meaning designed to trigger insight and self-reflection in the reader. He is perhaps best known for his collections of humorous Mulla Nasrudin stories.

Shah was at times criticized by orientalists who questioned his credentials and background. His role in the controversy surrounding a new translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, published by his friend Robert Graves and his older brother Omar Ali-Shah, came in for particular scrutiny. However, he also had many notable defenders, chief among them the novelist Doris Lessing. Shah came to be recognized as a spokesman for Sufism in the West and lectured as a visiting professor at a number of Western universities. His works have played a significant part in presenting Sufism as a form of spiritual wisdom approachable by individuals and not necessarily attached to any specific religion.

Life

Family and early life

Idries Shah was born in Simla, Punjab Province, British India, to an Afghan-Indian father of Pashtun descent; Sirdar Ikbal Ali Shah, a writer and diplomat, and a Scottish mother; Saira Elizabeth Luiza Shah. His family on the paternal side were Musavi Sayyids. Their ancestral home was near the Paghman Gardens of Kabul, Afghanistan. His paternal grandfather, Sayed Amjad Ali Shah, was the nawab of Sardhana in the North-Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, a hereditary title the family had gained thanks to the services an earlier ancestor, Jan-Fishan Khan, had rendered to the British.

Shah mainly grew up in the vicinity of London. According to L. F. Rushbrook Williams, Shah began accompanying his father in his travels from a very young age, and although they both travelled widely and often, they always returned to England, where the family made their home for many years. Through these travels, which were often part of Ikbal Ali Shah's Sufi work, Shah was able to meet and spend time with prominent statesmen and distinguished personalities in both East and West. Williams writes,

Such an upbringing presented to a young man of marked intelligence, such as Idries Shah soon proved himself to possess, many opportunities to acquire a truly international outlook, a broad vision, and an acquaintance with people and places that any professional diplomat of more advanced age and longer experience might well envy. But a career of diplomacy did not attract Idries Shah...

Shah described his own unconventional upbringing in a 1971 BBC interview with Pat Williams. He described how his father and his extended family and friends always tried to expose the children to a "multiplicity of impacts" and a wide range of contacts and experiences with the intention of producing a well-rounded person. Shah described this as "the Sufi approach" to education.

After his family moved from London to Oxford in 1940 to escape The Blitz (German bombing), he spent two or three years at the City of Oxford High School for Boys. In 1945, he accompanied his father to Uruguay as secretary to his father's halal meat mission. He returned to England in October 1946, following allegations of improper business dealings.

Personal life

Shah married the Parsi-Zoroastrian Cynthia (Kashfi) Kabraji, daughter of Indian poet Fredoon Kabraji, in 1958; they had a daughter, Saira Shah, in 1964, followed by twins – a son, Tahir Shah, and another daughter, Safia Shah – in 1966.

Friendship with Gerald Gardner and Robert Graves, and publication of The Sufis

Towards the end of the 1950s, Shah established contact with Wiccan circles in London and then acted as a secretary and companion to Gerald Gardner, the founder of modern Wicca, for some time. In those days, Shah used to hold court for anyone interested in Sufism at a table in the Cosmo restaurant in Swiss Cottage (North London) every Tuesday evening.

In 1960, Shah founded his publishing house, Octagon Press; one of its first titles was Gardner's biography – Gerald Gardner, Witch. The book was attributed to one of Gardner's followers, Jack L. Bracelin, but had in fact been written by Shah.

According to Wiccan Frederic Lamond, Bracelin's name was used because Shah "did not want to confuse his Sufi students by being seen to take an interest in another esoteric tradition." Lamond said that Shah seemed to have become somewhat disillusioned with Gardner, and had told him one day, when he was visiting for tea:

When I was interviewing Gerald, I sometimes wished I was a News of the World reporter. What marvellous material for an exposé! And yet I have it on good authority that this group will be the cornerstone of the religion of the coming age. But rationally, rationally I can't see it!

In January 1961, while on a trip to Mallorca with Gardner, Shah met the English poet Robert Graves. Shah wrote to Graves from his pension in Palma, requesting an opportunity of "saluting you one day before very long". He added that he was currently researching ecstatic religions, and that he had been "attending... experiments conducted by the witches in Britain, into mushroom-eating and so on" – a topic that had been of interest to Graves for some time.

Shah also told Graves that he was "intensely preoccupied at the moment with the carrying forward of ecstatic and intuitive knowledge." Graves and Shah soon became close friends and confidants. Graves took a supportive interest in Shah's writing career and encouraged him to publish an authoritative treatment of Sufism for a Western readership, along with the practical means for its study; this was to become The Sufis. Shah managed to obtain a substantial advance on the book, resolving temporary financial difficulties.

In 1964, The Sufis appeared, published by Doubleday, Robert Graves's American publisher, with a long introduction by Graves. The book chronicles the impact of Sufism on the development of Western civilisation and traditions from the seventh century onward through the work of such figures as Roger Bacon, John of the Cross, Raymond Lully, Chaucer and others. Like Shah's other books on the topic, The Sufis was conspicuous for avoiding terminology that might have identified his interpretation of Sufism with traditional Islam.

The book also employed a deliberately "scattered" style; Shah wrote to Graves that its aim was to "de-condition people, and prevent their reconditioning"; had it been otherwise, he might have used a more conventional form of exposition. The book sold poorly at first, and Shah invested a considerable amount of his own money in advertising it. Graves told him not to worry; even though he had some misgivings about the writing, and was hurt that Shah had not allowed him to proofread it before publication, he said he was "so proud in having assisted in its publication", and assured Shah that it was "a marvellous book, and will be recognised as such before long. Leave it to find its own readers who will hear your voice spreading, not those envisaged by Doubleday."

John G. Bennett and the Gurdjieff connection

In June 1962, a couple of years prior to the publication of The Sufis, Shah had also established contact with members of the movement that had formed around the mystical teachings of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky. A press article had appeared, describing the author's visit to a secret monastery in Central Asia, where methods strikingly similar to Gurdjieff's methods were apparently being taught. The otherwise unattested monastery had, it was implied, a representative in England.

One of Ouspensky's earliest pupils, Reggie Hoare, who had been part of the Gurdjieff work since 1924, made contact with Shah through that article. Hoare "attached special significance to what Shah had told him about the enneagram symbol and said that Shah had revealed secrets about it that went far beyond what we had heard from Ouspensky." Through Hoare, Shah was introduced to other Gurdjieffians, including John G. Bennett, a noted Gurdjieff student and founder of an "Institute for the Comparative Study of History, Philosophy and the Sciences" located at Coombe Springs, a 7-acre (2.8-hectare) estate in Kingston upon Thames, Surrey.

At that time, Bennett had already investigated the Sufi origins of many of Gurdjieff's teachings, based on both Gurdjieff's own numerous statements, and on travels Bennett himself made in the East where he met various Sufi Sheikhs. He was convinced that Gurdjieff had adopted many of the ideas and techniques of the Sufis and that, for those who heard Gurdjieff's lectures in the early 1920s, "the Sufi origin of his teaching was unmistakable to anyone who had studied both."

Bennett wrote about his first meeting with Shah in his autobiography Witness (1974):

At first, I was wary. I had just decided to go forward on my own and now another 'teacher' had appeared. One or two conversations with Reggie convinced me that I ought at least to see for myself. Elizabeth and I went to dinner with the Hoares to meet Shah, who turned out to be a young man in his early 40s. He spoke impeccable English and but for his beard and some of his gestures might well have been taken for an English public school type. Our first impressions were unfavourable. He was restless, smoked incessantly and seemed too intent on making a good impression. Halfway through the evening, our attitude completely changed. We recognized that he was not only an unusually gifted man, but that he had the indefinable something that marks the man who has worked seriously upon himself... Knowing Reggie to be a very cautious man, trained moreover in assessing information by many years in the Intelligence Service, I accepted his assurances and also his belief that Shah had a very important mission in the West that we ought to help him to accomplish.

Shah gave Bennett a "Declaration of the People of the Tradition" and authorised him to share this with other Gurdjieffians. The document announced that there was now an opportunity for the transmission of "a secret, hidden, special, superior form of knowledge"; combined with the personal impression Bennett formed of Shah, it convinced Bennett that Shah was a genuine emissary of the "Sarmoung Monastery" in Afghanistan, an inner circle of Sufis whose teachings had inspired Gurdjieff.

For the next few years, Bennett and Shah had weekly private talks that lasted for hours. Later, Shah also gave talks to the students at Coombe Springs. Bennett says that Shah's plans included "reaching people who occupied positions of authority and power who were already half-consciously aware that the problems of mankind could no longer be solved by economic, political or social action. Such people were touched, he said, by the new forces moving in the world to help mankind to survive the coming crisis."

Bennett agreed with these ideas and also agreed that "people attracted by overtly spiritual or esoteric movements seldom possessed the qualities needed to reach and occupy positions of authority" and that "there were sufficient grounds for believing that throughout the world there were already people occupying important positions, who were capable of looking beyond the limitations of nationality and cultures and who could see for themselves that the only hope for mankind lies in the intervention of a Higher Source."

Bennett wrote, "I had seen enough of Shah to know that he was no charlatan or idle boaster and that he was intensely serious about the task he had been given." Due to extreme pressure from Shah, Bennett decided in 1965, after agonising for a long time and discussing the matter with the council and members of his Institute, to give the Coombe Springs property to Shah, who had insisted that any such gift must be made with no strings attached. Once the property was transferred to Shah, he banned Bennett's associates from visiting, and made Bennett himself feel unwelcome.

Bennett says he did receive an invitation to the "Midsummer Revels", a party Shah held at Coombe Springs that lasted two days and two nights, primarily for the young people whom Shah was then attracting. Anthony Blake, who worked with Bennett for 15 years, says, "When Idries Shah acquired Coombe Springs, his main activity was giving parties. I had only a few encounters with him but much enjoyed his irreverent attitude. Bennett once said to me, 'There are different styles in the work. Mine is like Gurdjieff's, around struggle with one's denial. But Shah's way is to treat the work as a joke.'"

After a few months, Shah sold the plot – worth more than £100,000 – to a developer and used the proceeds to establish himself and his work activities at Langton House in Langton Green, near Tunbridge Wells, a 50-acre estate that once belonged to the family of Lord Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scouts.

Along with the Coombe Springs property, Bennett also handed the care of his body of pupils to Shah, comprising some 300 people. Shah promised he would integrate all those who were suitable; about half of their number found a place in Shah's work. Some 20 years later, the Gurdjieffian author James Moore suggested that Bennett had been duped by Shah. Bennett gave an account of the matter himself in his autobiography (1974); he said that Shah's behaviour after the transfer of the property was "hard to bear", but also insisted that Shah was a "man of exquisite manners and delicate sensibilities" and considered that Shah might have adopted his behaviour deliberately, "to make sure that all bonds with Coombe Springs were severed". He added that Langton Green was a far more suitable place for Shah's work than Coombe Springs could have been and said he felt no sadness that Coombe Springs lost its identity; he concluded his account of the matter by stating that he had "gained freedom" through his contact with Shah, and had learned "to love people whom [he] could not understand".

According to Bennett, Shah later also engaged in discussions with the heads of the Gurdjieff groups in New York. In a letter to Paul Anderson from 5 March 1968, Bennett wrote, "Madame de Salzmann and all the others... are aware of their own limitations and do no more than they are able to do. While I was in New York, Elizabeth and I visited the Foundation, and we saw most of the leading people in the New York group as well as Jeanne de Salzmann herself. Something is preparing, but whether it will come to fruition I cannot tell. I refer to their connection with Idries Shah and his capacity for turning everything upside down. It is useless with such people to be passive, and it is useless to avoid the issue. For the time being, we can only hope that some good will come, and meanwhile continue our own work..."

The author and clinical psychologist Kathleen Speeth later wrote,

Witnessing the growing conservatism within the [Gurdjieff] Foundation, John Bennett hoped new blood and leadership would come from elsewhere... Although there may have been flirtation with Shah, nothing came of it. The prevailing sense [among the leaders of the Gurdjieff work] that nothing must change, that a treasure in their safekeeping must at all costs be preserved in its original form, was stronger than any wish for a new wave of inspiration."

Sufi studies and institutes

In 1965, Shah founded the Society for Understanding Fundamental Ideas (SUFI), later renamed The Institute for Cultural Research (ICR) – an educational charity aimed at stimulating "study, debate, education and research into all aspects of human thought, behaviour and culture". He also established the Society for Sufi Studies (SSS).

Langton House at Langton Green became a place of gathering and discussion for poets, philosophers and statesmen from around the world, and an established part of the literary scene of the time. The ICR held meetings and gave lectures there, awarding fellowships to international scholars including Sir John Glubb, Aquila Berlas Kiani, Richard Gregory and Robert Cecil, the head of European studies at the University of Reading who became chairman of the institute in the early 1970s.

Shah was an early member and supporter of the Club of Rome. Fellow Club of Rome members, such as scientist Alexander King made presentations at the Institute.

Other visitors, pupils, and would-be pupils included the poet Ted Hughes, novelists J. D. Salinger, Alan Sillitoe and Doris Lessing, zoologist Desmond Morris, and psychologist Robert Ornstein. The interior of the house was decorated in a Middle-Eastern fashion, and buffet lunches were held every Sunday for guests in a large dining room that was once the estate stable, nicknamed "The Elephant" (a reference to the Eastern tale of the "Elephant in the Dark").

Over the following years, Shah developed Octagon Press as a means of publishing and distributing reprints of translations of numerous Sufi classics. In addition, he collected, translated and wrote thousands of Sufi tales, making these available to a Western audience through his books and lectures. Several of Shah's books feature the Mullah Nasruddin character, sometimes with illustrations provided by Richard Williams. In Shah's interpretation, the Mulla Nasruddin stories, previously considered a folkloric part of Muslim cultures, were presented as Sufi parables.

Nasruddin was featured in Shah's television documentary Dreamwalkers, which aired on the BBC in 1970. Segments included Richard Williams being interviewed about his unfinished animated film about Nasruddin, and scientist John Kermisch discussing the use of Nasruddin stories at the Rand Corporation Think Tank. Other guests included the British psychiatrist William Sargant discussing the hampering effects of brainwashing and social conditioning on creativity and problem-solving, and the comedian Marty Feldman talking with Shah about the role of humour and ritual in human life. The program ended with Shah asserting that humanity could further its own evolution by "breaking psychological limitations" but that there was a "constant accretion of pessimism which effectively prevents evolution in this form from going ahead... Man is asleep – must he die before he wakes up?"

Shah also organised Sufi study groups in the United States. Claudio Naranjo, a Chilean psychiatrist who was teaching in California in the late 1960s, says that, after being "disappointed in the extent to which Gurdjieff's school entailed a living lineage", he had turned towards Sufism and had "become part of a group under the guidance of Idries Shah." Naranjo co-wrote a book with Robert Ornstein, entitled On The Psychology of Meditation (1971). Both of them were associated with the University of California, where Ornstein was a research psychologist at the Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute.

Ornstein was also president and founder of the Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge, established in 1969; seeing a need in the U.S. for books and collections on ancient and new ways of thinking, he formed the ISHK Book Service in 1972 as a central source for important contemporary and traditional literature, becoming the sole U.S. distributor of the works of Idries Shah published by Octagon Press.

Another Shah associate, the scientist and professor Leonard Lewin, who was teaching telecommunications at the University of Colorado at the time, set up Sufi study groups and other enterprises for the promotion of Sufi ideas like the Institute for Research on the Dissemination of Human Knowledge (IRDHK), and also edited an anthology of writings by and about Shah entitled The Diffusion of Sufi Ideas in the West (1972).

The planned animated feature film by Williams, provisionally titled The Amazing Nasruddin, never materialised, as the relationship between Williams and the Shah family soured in 1972 amid disputes about copyrights and funds; however, Williams later used some of the ideas for his film The Thief and the Cobbler.

Later years

Shah wrote around two dozen more books over the following decades, many of them drawing on classical Sufi sources. Achieving a huge worldwide circulation, his writings appealed primarily to an intellectually oriented Western audience. By translating Sufi teachings into contemporary psychological language, he presented them in vernacular and hence accessible terms. His folktales, illustrating Sufi wisdom through anecdote and example, proved particularly popular. Shah received and accepted invitations to lecture as a visiting professor at academic institutions including the University of California, the University of Geneva, the National University of La Plata and various English universities. Besides his literary and educational work, he found time to design an air ioniser (forming a company together with Coppy Laws) and run a number of textile, ceramics and electronics companies. He also undertook several journeys to his ancestral Afghanistan and involved himself in setting up relief efforts there; he drew on these experiences later on in his book Kara Kush, a novel about the Soviet–Afghan War.

Illness

In late spring of 1987, about a year after his final visit to Afghanistan, Shah suffered two successive and massive heart attacks. He was told that he had only eight per cent of his heart function left, and could not expect to survive. Despite intermittent bouts of illness, he continued working and produced further books over the next nine years.

Death

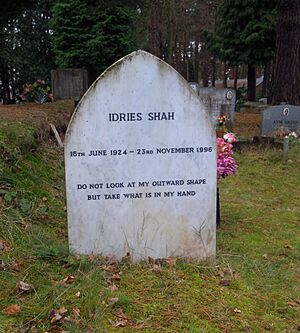

Idries Shah died in London on 23 November 1996, at the age of 72 and was buried in Brookwood Cemetery. According to his obituary in The Daily Telegraph, Idries Shah was a collaborator with Mujahideen in the Soviet–Afghan War, a Director of Studies for the Institute for Cultural Research and a Governor of the Royal Humane Society and the Royal Hospital and Home for Incurables. He was also a member of the Athenaeum Club. At the time of his death, Shah's books had sold over 15 million copies in a dozen languages worldwide, and had been reviewed in numerous international journals and newspapers.

Teachings

Books on magic and the occult

Shah's early books were studies of what he called "minority beliefs". His first book Oriental Magic, published in 1956, was originally intended to be titled Considerations in Eastern and African Minority Beliefs. He followed this in 1957 with The Secret Lore of Magic: Book of the Sorcerers, originally entitled Some Materials on European Minority-Belief Literature. The names of these books were, according to a contributor to a 1973 festschrift for Shah, changed before publication due to the "exigencies of commercial publishing practices."

Before his death in 1969, Shah's father asserted that the reason why he and his son had published books on the subject of magic and the occult was "to forestall a probable popular revival or belief among a significant number of people in this nonsense. My son... eventually completed this task, when he researched for several years and published two important books on the subject."

In an interview in Psychology Today from 1975, Shah elaborated:

The main purpose of my books on magic was to make this material available to the general reader. For too long people believed that there were secret books, hidden places, and amazing things. They held onto this information as something to frighten themselves with. So the first purpose was information. This is the magic of East and West. That's all. There is no more. The second purpose of those books was to show that there do seem to be forces, some of which are either rationalized by this magic or may be developed from it, which do not come within customary physics or within the experience of ordinary people. I think this should be studied, that we should gather the data and analyze the phenomena. We need to separate the chemistry of magic from the alchemy, as it were.

Shah went on to say that his books on the subject were not written for the current devotees of magic and witchcraft, and that in fact he subsequently had to avoid them, as they would only be disappointed in what he had to say.

These books were followed by the publication of the travelogue Destination Mecca (1957), which was featured on television by Sir David Attenborough. Both Destination Mecca and Oriental Magic contain sections on the subject of Sufism.

Sufism as a form of timeless wisdom

Shah presented Sufism as a form of timeless wisdom that predated Islam. He emphasised that the nature of Sufism was alive, not static, and that it always adapted its visible manifestations to new times, places and people: "Sufi schools are like waves which break upon rocks: [they are] from the same sea, in different forms, for the same purpose," he wrote, quoting Ahmad al-Badawi.

Shah was often dismissive of orientalists' descriptions of Sufism, holding that academic or personal study of its historical forms and methods was not a sufficient basis for gaining a correct understanding of it. In fact, an obsession with its traditional forms might actually become an obstacle: "Show a man too many camels' bones, or show them to him too often, and he will not be able to recognise a camel when he comes across a live one," is how he expressed this idea in one of his books.

Shah, like Inayat Khan, presented Sufism as a path that transcended individual religions, and adapted it to a Western audience. Unlike Khan, however, he deemphasised religious or spiritual trappings and portrayed Sufism as a psychological technology, a method or science that could be used to achieve self-realisation. In doing so, his approach seemed to be especially addressed to followers of Gurdjieff, students of the Human Potential Movement, and intellectuals acquainted with modern psychology. For example, he wrote, "Sufism ... states that man may become objective, and that objectivity enables the individual to grasp 'higher' facts. Man is therefore invited to push his evolution ahead towards what is sometimes called in Sufism 'real intellect'." Shah taught that the human being could acquire new subtle sense organs in response to need:

Sufis believe that, expressed in one way, humanity is evolving towards a certain destiny. We are all taking part in that evolution. Organs come into being as a result of the need for specific organs (Rumi). The human being's organism is producing a new complex of organs in response to such a need. In this age of transcending of time and space, the complex of organs is concerned with the transcending of time and space. What ordinary people regard as sporadic and occasional outbursts of telepathic or prophetic power are seen by the Sufi as nothing less than the first stirrings of these same organs. The difference between all evolution up to date and the present need for evolution is that for the past ten thousand years or so we have been given the possibility of a conscious evolution. So essential is this more rarefied evolution that our future depends upon it.

Shah dismissed other Eastern and Western projections of Sufism as "watered down, generalised or partial"; he included in this not only Khan's version, but also the overtly Muslim forms of Sufism found in most Islamic countries. On the other hand, the writings of Shah's associates implied that he was the "Grand Sheikh of the Sufis" – a position of authority undercut by the failure of any other Sufis to acknowledge its existence. Shah felt the best way to introduce Sufi wisdom in the West, while at the same time overcoming the problems of gurus and cults, was to clarify the difference between a cult and an educational system, and to contribute to knowledge. In an interview, he explained, "You must work within an educational pattern – not in the mumbo-jumbo area." As part of this approach, he acted as Director of Studies at the ICR. He also lectured on the study of Sufism in the West at the University of Sussex in 1966. This was later published as a monograph entitled Special Problems in the Study of Sufi Ideas.

Shah later explained that Sufi activities were divided into different components or departments: "studies in Sufism", "studies of Sufism", and "studies for Sufism".

Studies for Sufism helped lead people towards Sufism and included the promotion of knowledge which might be lacking in the culture and needed to be restored and spread, such as an understanding of social conditioning and brainwashing, the difference between the rational and intuitive modes of thought, and other activities so that people's minds could become more free and wide-ranging. Studies of Sufism included institutions and activities, such as lectures and seminars, which provided information about Sufism and acted as a cultural liaison between the Sufis and the public. Finally, Studies in Sufism referred to being in a Sufi school, carrying out those activities prescribed by the teacher as part of a training, and this could take many forms which did not necessarily fit into the preconceived notion of a "mystical school".

Shah's Sufi aims and methodologies were also delineated in the "Declaration of the People of the Tradition" given at Coombe Springs:

In addition to making this announcement, to feeding into certain fields of thought certain ideas, and pointing out some of the factors surrounding this work, the projectors of this declaration have a practical task. This task is to locate individuals who have the capacity for obtaining the special knowledge of man which is available; to group them in a special, not haphazard, manner, so that each such group forms a harmonious organism; to do this in the right place at the right time; to provide an external and interior format with which to work, as well as a formulation of 'ideas' suitable to local conditions; to balance theory with practice.

In a BBC interview from 1971, Shah explained his contemporary, adaptive approach: "I am interested in making available in the West those aspects of Sufism which shall be of use to the West at this time. I don't want to turn good Europeans into poor Asiatics. People have asked me why I don't use traditional methods of spiritual training, for instance, in dealing with people who seek me out or hunt me down; and of course, the answer is, that it's for the same reason that you came to my house today in a motorcar and not on the back of a camel. Sufism is, in fact, not a mystical system, not a religion, but a body of knowledge."

Shah frequently characterised some of his work as really only preliminary to actual Sufi study, in the same way that learning to read and write might be seen as preliminary to a study of literature: "Unless the psychology is correctly oriented, there is no spirituality, though there can be obsession and emotionality, often mistaken for it." "Anyone trying to graft spiritual practices upon an unregenerate personality ... will end up with an aberration", he argued. For this reason, most of the work he produced from The Sufis onwards was psychological in nature, focused on attacking the nafs-i-ammara, the false self: "I have nothing to give you except the way to understand how to seek – but you think you can already do that."

Shah was frequently criticised for not mentioning God very much in his writings; his reply was that given man's present state, there would not be much point in talking about God. He illustrated the problem in a parable in his book Thinkers of the East: "Finding I could speak the language of ants, I approached one and inquired, 'What is God like? Does he resemble the ant?' He answered, 'God! No indeed – we have only a single sting but God, He has two!'"

Teaching stories

Shah used teaching stories and humour to great effect in his work. Shah emphasised the therapeutic function of surprising anecdotes, and the fresh perspectives these tales revealed. The reading and discussion of such tales in a group setting became a significant part of the activities in which the members of Shah's study circles engaged. The transformative way in which these puzzling or surprising tales could destabilise the student's normal (and unaware) mode of consciousness was studied by Stanford University psychology professor Robert Ornstein, who along with fellow psychologist Charles Tart and eminent writers such as Poet Laureate Ted Hughes and Nobel-Prize-winning novelist Doris Lessing was one of several notable thinkers profoundly influenced by Shah.

Shah and Ornstein met in the 1960s. Realising that Ornstein could be an ideal partner in propagating his teachings, translating them into the idiom of psychotherapy, Shah made him his deputy (khalifa) in the United States. Ornstein's The Psychology of Consciousness (1972) was enthusiastically received by the academic psychology community, as it coincided with new interests in the field, such as the study of biofeedback and other techniques designed to achieve shifts in mood and awareness. Ornstein has published more books in the field over the years.

Philosopher of science and physicist Henri Bortoft used teaching tales from Shah's corpus as analogies of the habits of mind which prevented people from grasping the scientific method of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Bortoft's The Wholeness of Nature: Goethe's Way of Science includes tales from Tales of the Dervishes, The Exploits of the Incomparable Mullah Nasruddin and A Perfumed Scorpion.

In their original historical and cultural setting, Sufi teaching stories of the kind popularised by Shah – first told orally, and later written down for the purpose of transmitting Sufi faith and practice to successive generations – were considered suitable for people of all ages, including children, as they contained multiple layers of meaning. Shah likened the Sufi story to a peach: "A person may be emotionally stirred by the exterior as if the peach were lent to you. You can eat the peach and taste a further delight ... You can throw away the stone – or crack it and find a delicious kernel within. This is the hidden depth." It was in this manner that Shah invited his audience to receive the Sufi story. By failing to uncover the kernel, and regarding the story as merely amusing or superficial, a person would accomplish nothing more than looking at the peach, while others internalised the tale and allowed themselves to be touched by it.

Tahir Shah mentions his father's storytelling at several points throughout his 2008 book In Arabian Nights, first to discuss how Idries Shah made use of teaching stories: "My father never told us how the stories worked. He did not reveal the layers, the nuggets of information, the fragments of truth and fantasy. He didn't need to – because, given the right conditions, the stories activated, sowing themselves." He then explains how his father used these stories to impart wisdom: "My father always had a tale at hand to divert our attention, or to use as a way of transmitting an idea or a thought. He used to say that the great collections of stories from the East were like encyclopedias, storehouses of wisdom and knowledge ready to be studied, to be appreciated and cherished. To him, stories represented much more than mere entertainment. He saw them as complex psychological documents, forming a body of knowledge that had been collected and refined since the dawn of humanity and, more often than not, passed down by word of mouth."

Later on in the book, he continues his discussion of stories as teaching tools, quoting the following explanation his father gave him at the end of a story:

These stories are technical documents, they are like maps, or kind of blueprints. What I do is show people how to use the maps, because they have forgotten. You may think it's a strange way to teach – with stories – but long ago this was the way people passed on wisdom. Everyone knew how to take the wisdom from the story. They could see through the layers, in the same way you see a fish frozen in a block of ice. But the world where we are living has lost this skill, a skill they certainly once had. They hear the stories and they like them, because the stories amuse them, make them feel warm. But they can't see past the first layer, into the ice.

The stories are like a lovely chessboard: we all know how to play chess and we can be drawn into a game so complicated that our faculties are drained. But imagine if the game was lost from a society for centuries and then the fine chessboard and its pieces were found. Everyone would cluster round to see them and praise them. They might never imagine that such a fine object ever had a purpose other than to entertain the eyes. The stories' inner value has been lost in the same way. At one time everyone knew how to play with them, how to decipher them. But now the rules have been forgotten. It is for us to show people again how the game is played.

Olav Hammer, in Sufism in Europe and North America (2004), cites an example of such a story. It tells of a man who is looking for his key on the ground. When a passing neighbour asks the man whether this is in fact the place where he lost the key, the man replies, "No, I lost it at home, but there is more light here than in my own house.". Versions of this story have been known for many years in the West (see Streetlight effect). This is an example of the long-noted phenomenon of similar tales existing in many different cultures, which was a central idea in Shah's folktale collection World Tales.

Peter Wilson, writing in New Trends and Developments in the World of Islam (1998), quotes another such story, featuring a dervish who is asked to describe the qualities of his teacher, Alim. The dervish explains that Alim wrote beautiful poetry, and inspired him with his self-sacrifice and his service to his fellow man. His questioner readily approves of these qualities, only to find the dervish rebuking him: "Those are the qualities which would have recommended Alim to you." Then he proceeds to list the qualities which actually enabled Alim to be an effective teacher: "Hazrat Alim Azimi made me irritated, which caused me to examine my irritation, to trace its source. Alim Azimi made me angry, so that I could feel and transform my anger." He explains that Alim Azimi followed the path of blame, intentionally provoking vicious attacks upon himself, in order to bring the failings of both his students and critics to light, allowing them to be seen for what they really were: "He showed us the strange, so that the strange became commonplace and we could realise what it really is."

Views on culture and practical life

Shah's concern was to reveal essentials underlying all cultures, and the hidden factors determining individual behaviour. He discounted the Western focus on appearances and superficialities, which often reflected mere fashion and habit, and drew attention to the origins of culture and the unconscious and mixed motivations of people and the groups formed by them. He pointed out how both on the individual and group levels, short-term disasters often turn into blessings – and vice versa – and yet the knowledge of this has done little to affect the way people respond to events as they occur.

Shah did not advocate the abandonment of worldly duties; instead, he argued that the treasure sought by the would-be disciple should derive from one's struggles in everyday living. He considered practical work the means through which a seeker could do self-work, in line with the traditional adoption by Sufis of ordinary professions, through which they earned their livelihoods and "worked" on themselves.

Shah's status as a teacher remained indefinable; disclaiming both the guru identity and any desire to found a cult or sect, he also rejected the academic hat. Michael Rubinstein, writing in Makers of Modern Culture, concluded that "he is perhaps best seen as an embodiment of the tradition in which the contemplative and intuitive aspects of the mind are regarded as being most productive when working together."

Legacy

Idries Shah considered his books his legacy; in themselves, they would fulfil the function he had fulfilled when he could no longer be there. Promoting and distributing their teacher's publications has been an important activity or "work" for Shah's students, both for fund-raising purposes and for transforming public awareness. The ICR suspended its activities in 2013 following the formation of a new charity, The Idries Shah Foundation, while the SSS had ceased its activities earlier. The ISHK (Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge), headed by Ornstein, is active in the United States; after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, for example, it sent out a brochure advertising Afghanistan-related books authored by Shah and his circle to members of the Middle East Studies Association, thus linking these publications to the need for improved cross-cultural understanding.

When Elizabeth Hall interviewed Shah for Psychology Today in July 1975, she asked him: "For the sake of humanity, what would you like to see happen?" Shah replied: "What I would really want, in case anybody is listening, is for the products of the last 50 years of psychological research to be studied by the public, by everybody, so that the findings become part of their way of thinking (...) they have this great body of psychological information and refuse to use it."

Shah's brother, Omar Ali-Shah (1922–2005), was also a writer and teacher of Sufism; the brothers taught students together for a while in the 1960s, but in 1977 "agreed to disagree" and went their separate ways. Following Idries Shah's death in 1996, a fair number of his students became affiliated with Omar Ali-Shah's movement.

One of Shah's daughters, Saira Shah, became notable in 2001 for reporting on women's rights in Afghanistan in her documentary Beneath the Veil. His son, Tahir Shah, is a noted travel writer, journalist and adventurer.

Translations

Idries Shah's works have been translated into many languages, such as French, German, Latvian, Persian, Polish, Russian, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish and others.

Idries Shah work was relatively late to reach the Polish reader. The pioneering translation into Polish was done by specialist in Iranian studies and translator Ivonna Nowicka who rendered the Tales of the Dervishes of her own initiative in 1999–2000. After a few unsuccessful attempts, she managed to find a publisher, the WAM Publishing House, and the book was finally published in 2002. The Wisdom of the Fools and The Magic Monastery in her translation followed in 2002 and 2003, respectively.

Works

Studies in minority beliefs

Sufism

- The Sufis ISBN: 9781784790004 (1964)

- Tales of the Dervishes ISBN: 9781784790691 (1967)

- Caravan of Dreams ISBN: 9781784790127 (1968)

- Reflections ISBN: 9781784790189 (1968)

- The Way of the Sufi ISBN: 9781784790240 (1968)

- The Book of the Book ISBN: 9781784790783 (1969)

- Wisdom of the Idiots ISBN: 9781784790363 (1969)

- The Dermis Probe ISBN: 9781784790486 (1970)

- Thinkers of the East: Studies in Experientialism ISBN: 9781784790608 (1971)

- The Magic Monastery ISBN: 0-86304-058-6 (1972)

- The Elephant in the Dark – Christianity, Islam and the Sufis ISBN: 9781784791025 (1974)

- A Veiled Gazelle – Seeing How to See ISBN: 0-900860-58-8 (1977)

- Neglected Aspects of Sufi Study ISBN: 0-900860-56-1 (1977)

- Special Illumination: The Sufi Use of Humour ISBN: 0-900860-57-X (1977)

- A Perfumed Scorpion ISBN: 0-900860-62-6 (1978)

- Learning How to Learn ISBN: 0-900860-59-6 (1978)

- The Hundred Tales of Wisdom ISBN: 0-86304-049-7 (1978)

- Evenings with Idries Shah ISBN: 0-86304-008-X (1981)

- Letters and Lectures of Idries Shah ISBN: 0-86304-010-1 (1981)

- Observations ISBN: 0-86304-013-6 (1982)

- Seeker After Truth ISBN: 0-900860-91-X (1982)

- Sufi Thought and Action ISBN: 0-86304-051-9 (1990)

- The Commanding Self ISBN: 0-86304-066-7 (1994)

- Knowing How to Know ISBN: 0-86304-072-1 (1998)

Collections of Mulla Nasrudin stories

- The Exploits of the Incomparable Mulla Nasrudin ISBN: 0-86304-022-5 (1966)

- The Pleasantries of the Incredible Mulla Nasrudin ISBN: 0-86304-023-3 (1968)

- The Subtleties of the Inimitable Mulla Nasrudin ISBN: 0-86304-021-7 (1973)

- The World of Nasrudin ISBN: 0-86304-086-1 (2003)

Studies of the English

- Darkest England ISBN: 0-86304-039-X (1987)

- The Natives are Restless ISBN: 0-86304-044-6 (1988)

- The Englishman's Handbook ISBN: 0-86304-077-2 (2000)

Travel

- Destination Mecca ISBN: 0-900860-03-0 (1957)

Fiction

- Kara Kush, London: William Collins Sons and Co., Ltd. ISBN: 0-685-55787-1 (1986)

Folklore

- World Tales ISBN: 0-86304-036-5 (1979)

For children

- Neem the Half-Boy ISBN: 1-883536-10-3 (1998)

- The Farmer's Wife ISBN: 1-883536-07-3 (1998)

- The Lion Who Saw Himself in the Water ISBN: 1-883536-25-1 (1998)

- The Boy Without A Name ISBN: 1-883536-20-0 (2000)

- The Clever Boy and the Terrible Dangerous Animal ISBN: 1-883536-51-0 (2000)

- The Magic Horse ISBN: 1-883536-26-X (2001)

- The Man with Bad Manners ISBN: 1-883536-30-8 (2003)

- The Old Woman and The Eagle ISBN: 1-883536-27-8 (2005)

- The Silly Chicken ISBN: 1-883536-50-2 (2005)

- Fatima the Spinner and the Tent ISBN: 1-883536-42-1 (2006)

- The Man and the Fox ISBN: 1-883536-43-X (2006)

- The Onion ISBN: 978-1-78479-305-0 (2018)

- Speak First and Lose ISBN: 978-1-78479-241-1 (2018)

- The Ants and the Pen ISBN: 978-1-78479-309-8 (2018)

- The Horrible Dib Dib ISBN: 978-1-78479-341-8 (2019)

- After a Swim ISBN: 978-1-78479-342-5 (2019)

- The Tale of the Sands ISBN: 978-1-78479-340-1 (2019)

As Arkon Daraul

- A History of Secret Societies ISBN: 0-8065-0857-4 (1961)

- Witches and Sorcerers ISBN: 0-8065-0267-3 (1962)

As Omar Michael Burke

- Among the Dervishes (Octagon Press, 1973).

Audio interviews, seminars and lectures

- Shah, Idries, and Pat Williams. A Framework for New Knowledge. London: Seminar Cassettes, 1973. Sound recording.

- Shah, Idries. Questions and Answers. London: Seminar Cassettes, 1973. Sound recording.

- King, Alexander, Idries Shah, and Aurelio Peccei. The World-and Men. Seminar Cassettes, 1972. Sound recording.

- King, Alexander, et al. Technology: The Two-Edged Sword. London: Seminar Cassettes, 1972. Sound recording.

- Learning From Stories (1976 Lecture) ISBN: 1-883536-03-0 (1997)

- On the Nature of Sufi Knowledge (1976 Lecture) ISBN: 1-883536-04-9 (1997)

- An Advanced Psychology of the East (1977 Lecture) ISBN: 1-883536-02-2 (1997)

- Overcoming Assumptions that Inhibit Spiritual Development; previously entitled A Psychology of the East (1976 Lecture) ISBN: 1-883536-23-5 (2000)

Centenary

Materials to mark the centenary of Shah's birth, 16 June 2024.

- Tahir Shah (Ed), Idries Shah Centenary (8 volumes), (2024).

See also

- The Institute for Cultural Research (1965–2013)

- The Idries Shah Foundation (2013 onwards)