History of the cotton industry in Catalonia facts for kids

The cotton industry was the first and leading industry of Catalan industrialisation which led, by the mid 19th century, to Catalonia becoming the main industrial region of Spain. It is the one Mediterranean exception to the tendency of early industrialisation to be concentrated in northern Europe. In common with many European countries and the United States, the Catalan cotton industry was the first to apply the factory system and modern technology at scale.

The industry had its origins in the early 18th century, when printed cloth chintz (Catalan: indianes) was produced, stimulated by a government initiative to substitute imports and the opening up of the American colonies to Catalan merchants. Spinning was a late addition to the industry and took off after English spinning technology was introduced at the turn of the 19th century. Industrialisation of the industry occurred in the 1830s after adoption of the factory system, and the removal of restrictions by Britain on the emigration of expert labour (1825) and of machinery (1842). Steam power was introduced but the cost of imported coal and steam engines, led to the extensive use of hydraulic power from the late 1860s. Government policy saw the proliferation of more than 75 industrial colonies (Catalan: colònies industrials) on the rivers of rural Catalonia seeking hydraulic power, cheaper labour and land.

From the middle of the 19th century the industry was increasingly protected as the cost of raw cotton, energy & machinery in Spain made it difficult to compete globally. The industry came to rely almost entirely on the internal market and the remaining American colonies. From the Great Depression, the industry declined. There was increasing strife in Spain, a declining economy, civil war and then from 1939, the policy of autarky locked the industry out of the post WW2 global growth and investment. The opening of the Spanish economy in the 1960s, social change that caused the industrial colony system to collapse and the oil shock of the 1970s saw the effective end of the industry.

The industry left a legacy of extraordinary architecture. The cotton magnates encouraged and funded the best modernisme architectural achievements, whether they were factories, private residences or apartment buildings Often the buildings served as both the company headquarters and symbols of the owner's power, modernity and progressive spirit. They include Casa Batllo, Casa Calvet, Casa Terradas, Casa Burés and Fàbrica Casaramona. The Church of Colònia Güell is inscribed on the list of UNESCO world heritage. In addition there are outstanding buildings that date from the mid 19th including Palau Güell, the factories Vapor Vell, Can Batlló (one building of which today houses the L'Escola Industrial), and the Aymerich factory in Terrassa which now houses the National Museum of Science and Industry.

The industrial colonies modernised and industrialised rural Catalonia and their infrastructure houses many modern museums. Many of the turbines installed in the (now closed) colonies, continue to supply electricity to the national grid. The colonies were also a powerful magnet attracting labour and spurring territorial population redistribution across the country, with implications for the politics of today.

Contents

History

1650-1736 The chintz revolution

The first chintz or calicoes (Catalan: indianes) arrived in Barcelona about 1650 possibly as European re-export from Marseilles, then Europe's principle route to India. The arrival of calicoes in Europe was nothing short of a revolution in garments due to increased comfort, hygiene, lower cost and irresistible colours relative to existing silk and woolen garments. Imports increased rapidly.

Spain followed England and France to ban calico imports. Firstly in 1717 Asian textiles were banned, probably as a result of complaints from Cádiz & Seville merchants about the Philippines ruining their own re-export business to Mexico.

Then in 1728 the import of European made imitations of Asian textiles was banned in Spain. Additionally the edict had as one of its objectives to encourage a local, import-substituting weaving and printing industry in imitation of England. It did this by exempting from the ban, spun yarn from Malta and granting freedom from guild regulation. Although there was no direct investment from the Spanish Crown as there was for say wool, favouring an industry in this way was unique in Europe and was an important factor in the Catalan cotton industry's rapid growth and eventual size.

1736-1783 Chintz printing

The first printing in Barcelona, using the technique of wooden moulds or stamps, was on linen and occurred in 1736. With a demonstrated existing market, such printing businesses were set up by entrepreneurial merchants. This initial focus on printing can be contrasted with England, which, having banned pure cotton textiles but not the import of raw cotton, found its success in spinning and weaving (of linen/cotton mix).

In the early part of the 18th century, linen cloth had begun to be imported from Amsterdam in exchange for brandy.

As demand for brandy and wine to northern Europe grew, this international trade provided the basis for the entire transformation of the Catalan economy and the textile industry in particular. Firstly, as viticulture became more specialised and profitable, the ensuing prosperity led to increasing demand for manufactured goods like printed cloth.

Secondly the viticulture generated excess capital that could be invested in ship construction and increasing trade, importantly to the American colonies, and in ventures such as printed cloth manufacture (and as described in the next section, in machinery). This trade expanded through initiatives such as the Royal Barcelona Trading Company to the Indies and rapidly expanded in the last quarter of the 18th century after the Cádiz monopoly was abolished. Wine and brandy and increasingly printed cloth were exported and the return trade imported products that were inputs into the textile industry such as indigo and brazilwood amongst others Merchants also invested heaviy in the slave trade to Cuba after 1814 and for some ensuing decades.

Printing grew rapidly in Barcelona, stimulated by the period of rising population growth and prosperity in the second half of the eighteenth century that Spain enjoyed. Manufacturing took place in workshops that were built in the ground floors of buildings inside Barcelona's medieval walls. Local artisans lived around the Sant Pere neighbourhood where the Rec Comtal water source had traditionally been used for dying operations and fields for laying out cloth to dry. The number of such printing shops rose from 8 in 1750 to 41 in 1770 to more than 100 in 1786, more than any other city in Europe. In Mataró, by the end of the 1740s there were 11 businesses and approximately 470 looms and a total labour force of 1300.

The industry was concentrated in Barcelona due to the existence of artisans of the medieval textile guilds which provided a workforce with appropriate skills, once they had learnt the techniques from immigrants from Marseilles, Hamburg and Switzerland. Training in engraving and drawing provided by the Escola de Belles Arts founded by the Royal Barcelona Board of Trade in 1775 was crucial for industry growth.

1783-1832 Proto-industry

This period is termed pre-industrial or proto-industrial because it is characterised by a gradual expansion in spinning and weaving through putting-out throughout Catalonia and included, from around 1800, the first steps in introducing machinery which had been invented in England.

The European and American wars between 1793 and 1814 completely ruptured the previous rapid growth in indianes and emerging trading patterns and markets. Limited to the internal Spanish market, the industry was forced to incorporate spinning (which until then had not been an important component of the printing industry) and to improve its productivity through the adoption of English mechanical spinning.

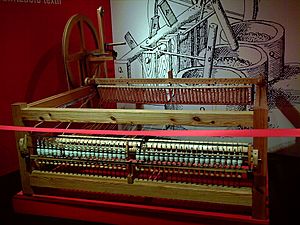

Although cotton spinning and weaving dates from the 1760s, it used traditional hand methods and did not really qualify as an industry until the 1790s. At the time most yarn arrived from Malta (made of Egyptian or Turkish cotton) but the capture of Malta by the English led to an 1802 royal edict banning the import of spun yarn. This forced the industry to become self sufficient in spinning. From about 1806, the adoption of the more advanced English spinning mule was facilitated by the Fontainebleau Pact which made it easy to purchase French copies of this technology.

Automation of the various processes can be seen from the dates of technology arriving in Catalonia. The first spinning jenny arrived in 1785 (21 years after its invention), the first water frame in 1793 (24 years after its invention) and the first spinning mule in 1806 (27 years after its invention). By 1820 the manufacture of cotton prints had only just returned the 1792 level, but now using local cotton yarn. By 1815 there were a total of 40 mules and jennies and by 1829 there were 410 mules and 30 jennies in Barcelona.

Unlike printing which was centred in Barcelona, spinning spread to other parts of Catalonia, partly due to the need for water power. Igualada became the most important spinning centre after Barcelona, followed by Manresa. Manresa had 11 water-driven spinning mills by 1831. Weaving became even more widespread than spinning with concentrations (in descending order of importance) in Mataro, Berga, Igualada, Reus, Vic, Manresa, Terrassa and Valls However weaving was slower to mechanise: by 1861 only 44% were mechanical.

Printing also advanced in this period, with the cylindrical printing process introduced in 1817.

The wars between 1797 and 1814 also interrupted the brandy trade with northern Europe and combined with the rise of competition in the production of spirits (whisky from Scotland, Vodka from Russia), merchants instead developed a new market in brandy and wine to America and this encouraged raw cotton as a return trade. Still highly profitable, this trade provided the capital to purchase spinning and weaving machinery and the first steam engines.

The new machinery increased demand for raw cotton and the trade with the American colonies now began to import increasing quantities. Between 1804 and the end of the 1830s the volume imported quadrupled (to about 5 million kilograms), initially from the American colonies but after their loss, from the United States and Brazil.

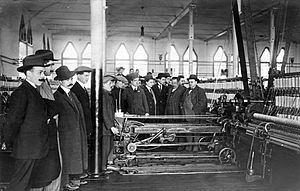

1832-1861 The great leap

The industrial era really began in 1833 with the installation of the first steam (Watt) engine in Spain at the new Bonaplata Factory (also called El Vapor) and enabled by the removal of restrictions by Britain on the emigration of expert labour in 1825. Contemporary writers termed this event as an industrial revolution as it also used machines made of cast iron for the first time. The company was formed by men from three main sectors of the industry: import and manufacture of machinery (Bonaplata) who made extensive visits to England, printing (Rull) and spinning and weaving (Vilaregut).

The Spanish Government agreed to support the company. The factory received a subsidy, the banning of all cotton imports and the right to import some materials and equipment duty-free. In return the company promised to manufacturer power looms and spinning machines for local purchase and to grant free access to any manufacture wanting to learn the steam technology, essentially a technology transfer to the rest of the Kingdom.

This period represented a great leap of industrialisation in which the mechanisation of the cotton spinning and weaving was simultaneous with the first pouring of cast iron, the nationalisation of lands held in mortmain and thus an increase in agricultural production, and a large increase in population. There was a new wave of general prosperity from higher wages and the repatriation of capital from the colonies after they won their independence and the adoption of factory system. Within a year of Bonaplata's formation, five more companies had raised the capital to import and install steam engines. Once Britain removed restrictions on machinery exports in 1842, British machine makers embarked on an export drive. By 1846 there were 80 steam engines operating.

The number of boats laden with raw cotton arriving in Barcelona skyrocketed from 12 in 1827 to 65 in 1835 to 140 in 1840, the vast majority from Cuba and Puerto Rico. By 1860, 18,000 tonnes of cotton were imported, 10 times more than in 1820.

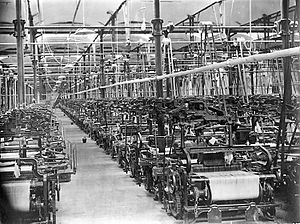

From the late 1830s, the industry had outgrown the walled city of Barcelona, and the steam engines with their frequent explosions scared everybody. Soon, factories were being established in the villages of Gracia, Sant Andreu, Sant Martí and Sants which became the new industrial suburbs long before they were incorporated into Greater Barcelona.

Industrialisation increased productivity and enabled a reduction in prices. By 1861, vertical integration predominated in the cotton industry, (spinning, weaving and finishing in one factory) in order to gain economies of scale and international competitiveness. Whereas in 1840 Spanish textiles were 81% more expensive to English ones, by 1860, mechanisation had brought that down to 14%. The price of printed cotton in Catalunya dropped 69% between 1831 and 1859 and drove producers in other parts of Spain out of the market. For example, the price of linen cloth, primarily produced in Galicia, did not change over the same period and so the linen industry evaporated. At the same time, the cotton industry stimulated wool textile production in Sabadell, Tarrasa and Manresa, with the consequent decline of the traditional woolen centers of Castille.

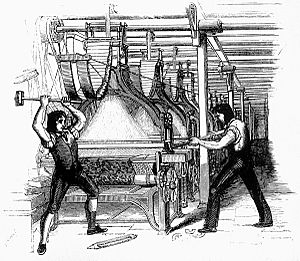

Industrialisation also implied social dislocation and conflict. In 1835, the Bonaplata Factory was attacked and burnt. In 1839 the first union in Spain was formed, the Association of Weavers of Barcelona. In 1842 there was a revolt in Barcelona against the free market policies of the Government which threatened industry and workers. Between 1849 and 1862, wages dropped 11% with 54% spent of food alone; life expectancy was 50 years for salaried workers and 40 for day workers. In 1854–1855, the Conflict of the selfactinas in Barcelona involved Luddite type action against the mechanisation of spinning facilitated by the "self-acting" or automatic spinning machines that was blamed for the forced unemployment of many workers. They burnt factories and demanded the removal of the spinning machines, reduced hours and a right to a minimum wage. The action led to the first general strike in Spain.

In spite of industrialisation, the industry was finding it hard to compete with foreign importers and called for tariff protection. A persistent problem was the higher cost of raw materials and machinery. From 1830 to 1844 the cost of raw cotton was on average 47% higher in Barcelona than New York and 28% higher than Liverpool. Coal prices in Barcelona were 76% higher than in Britain during this period, largely due to shipping costs (from Britain) and tariffs. Machinery and parts were also imported from Britain and were up to three times more than in Britain for the same reasons. On the other hand, wages in Catalonia were about 15% cheaper than Lancashire. Additional problems were the extent of contraband entering the country, the smaller scale and lower productivity with respect to the British cotton industry, meant that without protection, competing directly as they were, the Catalan industry probably would have succumbed to British competition as Portugal's textile industry had succumbed. As a result, growth from this period forward, would only come from a protected internal market.

1861-1882 Industrial colonies

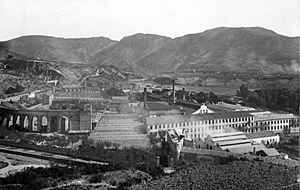

A series of laws in the 1850s and 1860s saw an expansion of the industry to rural Catalonia stimulated by the possibility of reducing costs.

Although the goal of the Agricultural Colonies Acts of 1855, 1866 and 1868 was to transform and modernise the Spanish countryside, industrial colonies would be covered by the Acts (and therefore exempt from industrial taxes for 10–25 years and workers exempt from military service) if they were established in a rural area. 142 industrial colonies around Spain, benefited from the Acts, 26 were textile companies, the second highest number after agro-food industry with 60 colonies). 15 of these 26 were located in the province of Barcelona. The majority of these 26 factories were vertically integrated: they undertook the entire range of cotton processes.

In addition, the Water Acts of 1866 and 1879 allowed water to be used as a free energy source (saving on imports of English coal), and also exempted any business doing so from paying industrial taxes for ten years. Some 17 Catalan industrial colonies benefited from this law.

These two initiatives, plus the fact that owners also found cheaper labour and land (than in Barcelona) and abundant raw materials from which to build their factories, led to a high intensity of development of factories along the rivers, perhaps the highest in Europe. Even more colonies were built in the 1870s after the American Civil War ended as raw cotton once again became readily available. The high concentration in the Ter and Llobregat rivers meant that railways could be constructed profitably, and from about 1880 linked local coal mines to industrial colonies (water was not always reliable), reduced the cost of supplying cotton to them and provided a cheaper means to bring the textiles to market.

In all, some 100 industrial colonies were built in Catalonia of which 77 were textile factories, and the majority of these were for cotton.

1882-1898 Protected trade with the Antilles

As over production become increasingly common and as domestic demand was inelastic, the textile industry lobbied government for more protection. The 1882 Commercial Relations with the Antilles Act effectively declared Cuba, Puerto Rico and Philippines as cabotage for Spain, meaning these American colonies were effectively forced to buy Spanish products and could not be undercut by foreign goods.

There was a prevailing protectionist attitude of the Spanish governments of the period, uniting the interests of not just textiles but also of the cereals and the iron and steel industry. The subsequent 1891 Canovas Tariff went further and has been described by one author as the first step towards corporatism, state involvement in business, a rejection of competition as a norm in business, and led logically after 1939 to autarky.

At the time, tariffs were the primary source of government revenues around the world. Proteccionism was proliferating in Europe. Elements of British society were advocating the re-introduction of tariffs and an exclusive trade bloc. In the US, a protectionist philosophy prevailed from the post-Civil War period until the 1930s. The 1894 US Wilson-Gorman Tariff imposed tariffs on sugar from Cuba (Cuba's main export) and cancelled a trade agreement with Spain that had reduced tariffs on food from the US to Cuba. Combined with the effect of the Spanish cabotage laws, within a few months this had re-ignited the war of independence in Cuba and which very soon resulted in Spain losing its possessions and with it the cotton market.

1898-1930 Turning inwards

At the point of the loss of the American colonial market, in 1900, the Catalan textile industry represented 56.8% of total Catalan manufacturing production and 82% of total textile production in Spain. Initially activity levels in the cotton industry fell drastically until 1903 and complicated by the general strike of 1902.

In spite of the set back, for the first couple of decades of the 20th century growth continued as a result of an expanding total and per capita Spanish national income and the expansion of the railway network which had reduced costs to deliver products internally.

There were modest attempts to find new foreign markets, and in the ten years to 1913 grew at an average rate of just over 5%. A temporary boom also resulted during WW1, especially supplying France.

However there were a number of factors that hindered expansion to foreign markets. Protectionist policies designed to protect grain production from Andalusia and Castile increased Catalan shipping costs in the Mediterranean. The earlier decision to chose a non-standard railway gauge for military defence reasons also proved an economic barrier to export.

Additionally the legacy of a being a protected market also meant that Catalan companies didn't have the sales and banking networks in foreign markets that they had in domestic markets and so were unwilling to take risks they took domestically. They were thus reticent to work through foreign distributors, ignoring requests or demanding commercial conditions that made them completely uncompetitive. Instead they viewed foreign markets as escape valves in times of overproduction. Consequently, they lost many opportunities to export their products and to build feed-back loop to improve their products or competitiveness.

Finally, the monetary policy of the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera from 1923, had the effect of harming all Spanish exports.

1930-1990 Decline and restructure

The Great Depression and then increasing strife led to a steep decline in the Spanish economy. Catalonia sank into stagnation and atrophy. WW2 completely disrupted the import of raw cotton from the Americas and post Civil War economic policy of autarky cutting off almost all international trade, ensured technological and managerial obsolescence and locked the industry out of the post WW2 global growth and reduced the opportunities for additional capital. The general decline in salaries and difficulty in importing machinery before 1959 meant that the industry maintained low levels of mechanisation and productivity.

When Spain began to open its economy in the 1960s, the industry faced a different world and significant adjustment occurred. The British cotton industry had already declined significantly between the world wars. In the US, polyester had been introduced in the 1950s, spandex was patented in 1959, Kevlar was produced in 1965, and by 1968, synthetic fibers surpassed natural fibers for the first time in history. Developing countries had begun to focus on clothing in their process of industrialisation, and so the industry in industrialised countries became more capital intensive. New machines such as open-end spinning and weaving using shuttleless looms had replaced older technology in the US. The European Commission had begun a process of opening the Common Market to developing world producers.

The industrial colony system had already began to collapse in the 1960s due to its inflexible capital structure (family owned) and social changes such as the desire for workers to own appliances, cars, or their own home, the declining influence of religion, and the opportunities offered by towns. By the 1980s and 1990s almost all the factories in these industrial colonies closed.

The Government's 1969 Plan for the restructure of the cotton textile industry encompassed closing marginal companies, destroying outdated machinery and reducing the workforce, ideally by re-allocation to new manufacturing sectors such as automobiles, metal processing, plastics, synthetic fibres and chemicals. Employment in the industry declined from 228,000 in 1958 to 133,000 in 1978. The cotton manufacturing industry suffered a major crisis as a result of the inflationary global oil shock and by 1980 could not compete with either “cheap” countries (Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania) or advanced countries with lower production costs and higher productivity (Europe, the United States and Japan). Entry to the EU in 1986 resulted in more intense adjustment so that today, the industry employs 5,000.

The company La España Industrial provides bookends to the industry. It was not only the first joint-stock company (Spanish: sociedad anónima) formed in Spain for cotton manufacturing, it was the first to encompass spinning, weaving and finishing under one roof. It was formed in 1847, grew to 2,500 employees in late 19th century, consolidated factories in the 1960s and finally closed its doors for good in 1981. Can Batlló stopped textile production in 1964 and Colònia Güell was closed in 1973. Colònia Sedó, which had been the largest such industrial colony in Spain in the 1930s, closed in 1980.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la industria del algodón en Cataluña para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la industria del algodón en Cataluña para niños