History of the Puritans from 1649 facts for kids

From 1649 to 1660, Puritans in the Commonwealth of England were allied to the state power held by the military regime, headed by Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell until he died in 1658. They broke into numerous sects, of which the Presbyterian group comprised most of the clergy, but was deficient in political power since Cromwell's sympathies were with the Independents. During this period, the term "Puritan" becomes largely moot, therefore, in British terms, though the situation in New England was very different. After the English Restoration, the Savoy Conference and Uniformity Act 1662 and Great Ejection drove most of the Puritan ministers from the Church of England, and the outlines of the Puritan movement changed over a few decades into the collections of Presbyterian and Congregational churches, operating as they could as Dissenters under changing regimes.

Contents

English Interregnum, 1649–1660

Failure of the Presbyterian church, 1649–1654

The English Interregnum was a period of religious diversity in England. With the creation of the Commonwealth of England in 1649, the government passed to the English Council of State, a group dominated by Oliver Cromwell, an advocate of religious liberty. In 1650, at Cromwell's behest, the Rump Parliament abolished the Act of Uniformity 1558, meaning that while England now had an officially established church with Presbyterian polity, there was no legal requirement that anyone attend services in the established church.

In 1646, the Long Parliament had abolished episcopacy in the Church of England and replaced it with a presbyterian system, and had voted to replace the Book of Common Prayer with the Directory of Public Worship. The actual implementation of these reforms in the church proceeded slowly for a number of reasons:

- In many localities – especially those areas which had been Royalist during the Civil Wars and which had low numbers of Puritans, both the bishops and the Book of Common Prayer were popular, and ministers, as well as their congregations, simply continued to conduct worship in their ordinary way.

- Independents opposed the scheme, and started conducting themselves as gathered churches.

- Clergymen who favored presbyterianism nevertheless disliked the Long Parliament's ordinance because it included an Erastian element in the office of "commissioner". Some were thus less than enthusiastic about implementing the Long Parliament's scheme.

- Since the office of bishop had been abolished in the church, with no substitute, there was no one to enforce the new presbyterianism scheme on the church, so the combination of opposition and apathy meant that little was done.

With the abolition of the Act of Uniformity, even the pretense of religious uniformity broke down. Thus, while the Presbyterians were dominant (at least theoretically) within the established church, those who opposed Presbyterianism were in fact free to start conducting themselves in the way they wanted. Separatists, who had previously organized themselves underground, were able to worship openly. For example, as early as 1616, the first English Baptists had organized themselves in secret, under the leadership of Henry Jacob, John Lothropp, and Henry Jessey. Now, however, they were less secretive. Other ministers – who favored the congregationalist New England Way – also began setting up their own congregations outside of the established church.

Many sects were also organized during this time. It is not clear that they should be called "Puritan" sects since they placed less emphasis on the Bible than is characteristic of Puritans, instead insisting on the role of direct contact with the Holy Spirit. These groups included the Ranters, the Fifth Monarchists, the Seekers, the Muggletonians, and – most prominently and most lastingly – the Quakers.

From 1660 to present day

Puritans and the Restoration, 1660

The largest Puritan faction – the Presbyterians – had been deeply dissatisfied with the state of the church under Cromwell. They wanted to restore religious uniformity throughout England and they believed that only a restoration of the English monarchy could achieve this and suppress the sectaries. Most Presbyterians were therefore supportive of the Restoration of Charles II. Charles II's most loyal followers – those who had followed him into exile on the continent, like Sir Edward Hyde – had fought the English Civil War largely in defense of episcopacy and insisted that episcopacy be restored in the Church of England. Nevertheless, in the Declaration of Breda, issued in April 1660, a month before Charles II's return to England, Charles II proclaimed that while he intended to restore the Church of England, he would also pursue a policy of religious toleration for non-adherents of the Church of England. Charles II named the only living pre-Civil War bishop William Juxon as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1660, but it was widely understood that because of Juxon's age, he would likely die soon and be replaced by Gilbert Sheldon, who, for the time being, became Bishop of London. In a show of goodwill, one of the chief Presbyterians, Edward Reynolds, was named Bishop of Norwich and chaplain to the king.

Shortly after Charles II's return to England, in early 1661, Fifth Monarchists Vavasor Powell and Thomas Venner attempted a coup against Charles II. Thus, elections were held for the Cavalier Parliament in a heated atmosphere of anxiety about a further Puritan uprising.

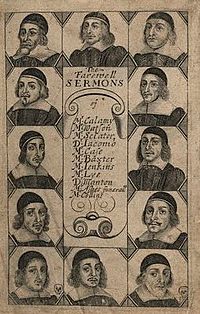

Nevertheless, Charles II had hoped that the Book of Common Prayer could be reformed in a way that was acceptable to the majority of the Presbyterians, so that when religious uniformity was restored by law, the largest number of Puritans possible could be incorporated inside the Church of England. At the April 1661 Savoy Conference, held at Gilbert Sheldon's chambers at Savoy Hospital, twelve bishops and twelve representatives of the Presbyterian party (Edward Reynolds, Anthony Tuckney, John Conant, William Spurstowe, John Wallis, Thomas Manton, Edmund Calamy, Richard Baxter, Arthur Jackson, Thomas Case, Samuel Clarke, and Matthew Newcomen) met to discuss Presbyterian proposals for reforming the Book of Common Prayer drawn up by Richard Baxter. Baxter's proposed liturgy was largely rejected at the Conference.

When the Cavalier Parliament met in May 1661, its first action, largely a reaction to the Fifth Monarchist uprising, was to pass the Corporation Act of 1661, which barred anyone who had not received communion in the Church of England in the past twelve months from holding office in a city or corporation. It also required officeholders to swear the Oath of Allegiance and Oath of Supremacy, to swear belief in the Doctrine of Passive Obedience, and to renounce the Covenant.

The Great Ejection, 1662

In 1662, the Cavalier Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity of 1662, restoring the Book of Common Prayer as the official liturgy under the 1662 prayer book. The Act of Uniformity prescribed that any minister who refused to conform to the Book of Common Prayer by St. Bartholomew's Day 1662 would be ejected from the Church of England. This date became known as Black Bartholomew's Day, among dissenters, a reference to the fact that it occurred on the same day as the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of 1572.

The majority of ministers who had served in Cromwell's state church conformed to the Book of Common Prayer. Members of Cromwell's state church who chose to conform in 1662 were often labeled Latitudinarians by contemporaries - this group includes John Tillotson, Simon Patrick, Thomas Tenison, William Lloyd, Joseph Glanvill, and Edward Fowler. The Latitudinarians formed the basis of what would later become the Low church wing of the Church of England. The Puritan movement had become particularly fractured in the course of the 1640s and 1650s, and with the decision of the Latitudinarians to conform in 1662, it became even further fractured.

Around two thousand Puritan ministers resigned from their positions as Church of England clergy as a consequence. This group included Richard Baxter, Edmund Calamy the Elder, Simeon Ashe, Thomas Case, William Jenkyn, Thomas Manton, William Sclater, and Thomas Watson. After 1662, the term "Puritan" was generally supplanted by "Nonconformist" or "Dissenter" to describe those Puritans who had refused to conform in 1662.

Persecution of Dissenters, 1662–1672

Though expelled from their pulpits in 1662, many of the non-conforming ministers continued to preach to their followers in public homes and other locations. These private meetings were known as conventicles. The congregations that they formed around the non-conforming ministers at this time form the nucleus for the later English Presbyterian, Congregationalist, and Baptist denominations. The Cavalier Parliament responded hostilely to the continued influence of the non-conforming ministers. In 1664, it passed the Conventicle Act banning religious assemblies of more than five people outside of the Church of England. In 1665, it passed the Five Mile Act, forbidding ejected ministers from living within five miles of a parish from which they had been banned, unless they swore an oath never to resist the king, or attempt to alter the government of Church or State. Under the penal laws forbidding religious dissent (generally known to history as the Clarendon Code), many ministers were imprisoned in the latter half of the 1660s. One of the most notable victims of the penal laws during this period (though he was not himself an ejected minister) was John Bunyan, a Baptist, who was imprisoned from 1660 to 1672.

At the same time that the Cavalier Parliament was ratcheting up the legal penalties against religious dissent, there were various attempts from the side of government and bishops, to establish a basis for "comprehension", a set of circumstances under which some dissenting ministers could return to the Church of England. These schemes for comprehension would have driven a wedge between Presbyterians and the group of Independents; but the discussions that took place between Latitudinarian figures in the Church and leaders such as Baxter and Manton never bridged the gap between Dissenters and the "high church" party in the Church of England, and comprehension ultimately proved impossible to achieve.

The Road to Religious Toleration for the Dissenters, 1672–1689

In 1670, Charles II had signed the Secret Treaty of Dover with Louis XIV of France. In this treaty he committed to securing religious toleration for the Roman Catholic recusants in England. In March 1672, Charles issued his Royal Declaration of Indulgence, which suspended the penal laws against the dissenters and eased restrictions on the private practice of Catholicism. Many imprisoned dissenters (including John Bunyan) were released from prison in response to the Royal Declaration of Indulgence.

The Cavalier Parliament reacted hostilely to the Royal Declaration of Indulgence. Supporters of the high church party in the Church of England resented the easing of the penal laws, while many across the political nation suspected that Charles II was plotting to restore Catholicism to England. The Cavalier Parliament's hostility forced Charles to withdraw the declaration of indulgence, and the penal laws were again enforceable. In 1673, Parliament passed the first Test Act, requiring all officeholders in England to abjure the doctrine of transubstantiation (thus ensuring that no Catholics could hold office in England).

Later trends

Puritan experience underlay the later Latitudinarian and Evangelical trends in the Church of England. Divisions between Presbyterian and Congregationalist groups in London became clear in the 1690s, and with the Congregationalists following the trend of the older Independents, a split became perpetuated. The Salters' Hall conference of 1719 was a landmark, after which many of the congregations went their own way in theology. In Europe, in the 17th and 18th centuries, a movement within Lutheranism parallel to puritan ideology (which was mostly of a Calvinist orientation) became a strong religious force known as pietism. In the United States, the Puritan settlement of New England was a major influence on American Protestantism.

With the start of the English Civil War in 1642, fewer settlers to New England were Puritans. The period of 1642 to 1659 represented a period of peaceful dominance in English life by the formerly discriminated Puritan population. Consequently, most felt no need to settle in the American colonies. Very few immigrants to the Colony of Virginia and other early colonies, in any case, were Puritans. Virginia was a repository for more middle class and "royalist" oriented settlers, who were leaving England following their loss of power during the English Commonwealth. Many migrants to New England who had looked for greater religious freedom found the Puritan theocracy to be repressive, examples being Roger Williams, Stephen Bachiler, Anne Hutchinson, and Mary Dyer. Puritan populations in New England, continued to grow, with many large and prosperous Puritan families. (See Estimated Population 1620–1780: Immigration to the United States.)