History of slavery in Florida facts for kids

The history of slavery in Florida predates the period of European colonization and was practiced by various indigenous peoples. Florida had some of the first African slaves in what is now the United States in 1526-1565, as well as the first emancipation of escaping slaves in 1687 and the first settlement of free blacks in 1735.

Few enslaved Africans were imported into Florida from Cuba in the period of Spanish colonial rule. Starting in 1687, slaves escaping from English colonies to the north were freed when they accepted Catholicism. Black slavery in the region was widely established after Florida came under British then American control. Slavery in Florida was theoretically abolished by the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Lincoln, though as the state was part of the Confederacy this had little effect.

Slavery in Florida did not end abruptly on one specific day. As news arrived of the end of the Civil War and the collapse of the Confederacy in the spring of 1865, slavery unofficially ended, as there were no more slave catchers or other authority to enforce the peculiar institution. Newly emancipated African Americans departed their plantations, often in search of relatives who were separated from their family. The end of slavery was made formal by the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865. Some of the characteristics of slavery, such as inability to leave a disagreeable situation, continued under sharecropping, convict leasing, and vagrancy laws. In the 20th and 21st centuries, conditions approximating slavery are found among marginal immigrant populations, especially migrant farm workers.

Contents

Spanish rule

First occupation

The first enslaved African in Florida, Estevanico, was brought to the area in 1528 as part of the Narváez expedition, which then continued on to Texas. More African slaves arrived in Florida in 1539 with Hernando de Soto.

When the Spanish founded the colonial settlement of San Agustín in 1565, the site already had enslaved Native Americans, whose ancestors had migrated from Cuba. The Spaniards did not bring many slaves to Florida as there was no work for them to do—no mines and no plantations. Very few Spaniards came to Florida; there were only three military/naval support outposts: St. Augustine, St. Marks, and what is today called Pensacola. Under Spanish, colonial rule the enslaved in Florida had rights. They could marry, own property, and purchase their own freedom. Free blacks, as long as they were Catholic, were not subject to legal discrimination. No one was born into slavery. Mixed "race" marriages were not illegal, and mixed "race" children could inherit property. This was "unthinkable" in the United States.

In October 1687, eleven enslaved Africans made their way from Carolina to Florida in a stolen canoe, and were emancipated by the Spanish authorities. A year later, Major William Dunlop, an officer in the Carolinaa militia, arrived in Florida to ask for compensation for Spanish attacks on Carolina and the return of the Africans to their enslaver, Governor Joseph Morton. The Spanish chose to compensate Morton instead, submitting a report to King Charles II on the event. On November 7, 1693, Charles II issued a decree freeing all slaves escaping from English North America who accepted Catholicism, similar to the May 29, 1680 Spanish decree for slaves escaping from the Lesser Antilles and the September 3, 1680 and June 1, 1685 decrees for escaping French slaves.

In the early 1700s, Spanish Florida was a hotbed for the raiding Native Americans from the northern Carolina and Georgia areas. Though they were left alone for the most part by one of the original raiding groups, the Westos, Spanish Florida was heavily targeted by the later raiding groups, the Yamasee and Creek. These raids, in which villages were destroyed and local Native Americans were either killed or captured to be later sold as slaves to English colonists, drove the local Native Americans to the hands of the Spanish, who attempted to protect them as best they could from the raids. However, the strength of the Spanish dwindled and as the raids continued the Spanish and Spanish-allied natives were forced to retreat farther and farther back into the peninsula. The raids were so frequent that there were few natives left to capture, and so the Yamasee and the Creek began bringing fewer and fewer slaves to the Carolina colonies and were unable to effectively continue the trade. The retreat of the Spanish was only ended when the Yamasee and Creek entered what would later be known as the Yamasee War with the Carolina colony.

Since 1688, Spanish Florida had attracted numerous fugitive slaves who escaped from the British North American colonies. Once the slaves reached Florida, the Spanish freed them if they converted to Roman Catholicism; males of age had to complete a military obligation. Many settled in Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, the first settlement of free blacks in North America, near St. Augustine. The church started recording baptisms and deaths there in 1735, and a fort was built in 1738, part of the perimeter defenses of San Agustin. The freed slaves knew the border areas well and led military raids, under their own black officers, against the Carolinas, and against Georgia, founded in 1731. Another smaller group settled along the Apalachicola River in remote northwest Florida, centered on Prospect Bluff, future site of the famous Negro Fort.

Second occupation

The former slaves also found refuge among the Creek and Seminole, Native Americans who had established settlements in Florida at the invitation of the Spanish government. In 1771, Governor John Moultrie wrote to the Board of Trade that "It has been a practice for a good while past, for negroes to run away from their Masters, and get into the Indian towns, from whence it proved very difficult to get them back." When British colonial officials in Florida pressured the Native Americans to return the fugitive slaves, they replied that they had "merely given hungry people food, and invited the slaveholders to catch the runaways themselves."

After the American Revolution, slaves from the State of Georgia and the South Carolina Low Country escaped to Florida. The U.S. Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory, including the 1817–1818 campaign by Andrew Jackson that became known as the First Seminole War. The United States afterwards effectively controlled East Florida. According to Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, the US had to take action there because Florida had become "a derelict open to the occupancy of every enemy, civilized or savage, of the United States, and serving no other earthly purpose than as a post of annoyance to them." Spain requested British intervention, but London declined to assist Spain in the negotiations. Some of President James Monroe's cabinet demanded Jackson's immediate dismissal, but Adams realized that it put the U.S. in a favorable diplomatic position, allowing him to negotiate very favorable terms.

The Spanish established outposts in Florida to prevent others from having safe ports to attack Spanish treasure fleets in the Caribbean and in the strait between Florida and the Bahamas. Florida did not produce anything the Spaniards wanted. The three garrisons were a financial drain, and it was not felt desirable to send settlers or additional garrisons. The Crown decided to cede the territory to the United States. It accomplished this through the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, which took effect in 1821.

Treatment of blacks under Spanish rule

Under the Spanish, enslaved workers had rights: to marry, to own property, to buy their own freedom. They were not chattel. Free blacks, as long as they were Catholic, were not subject to legal discrimination. No one was born into slavery. Mixed "race" marriages were not illegal, and mixed "race" children could inherit property.

British Florida

- Further information: British Florida

Florida under American rule

Florida became an organized territory of the United States on February 22, 1821. Slavery continued to be permitted.

Free negros were unwanted

The free blacks and Indian slaves, Black Seminoles, living near St. Augustine fled to Havana, Cuba, to avoid coming under US control. Some Seminole also abandoned their settlements and moved further south. Hundreds of Black Seminoles and fugitive slaves escaped in the early nineteenth century from Cape Florida to The Bahamas, where they settled on Andros Island, founding Nicholls Town, named for the Anglo-Irish commander and Abolitionist who fostered their escape, Edward Nicolls.

In 1827 free negros were prohibited from entering Florida, and in 1828 those already there were prohibited from assembling in public. In antebellum Florida, "Southerners came to believe that the only successful means of removing the threat of free Negroes was to expel them from the southern states or to change their status from free persons to... slaves." Free Negroes were perceived as "an evil of no ordinary magnitude," undermining the system of slavery. Slaves had to be shown that there was no advantage in being free; thus, free negroes became victims of the slaveholders' fears. Legislation became more forceful; the free negro had to accept his new role or leave the state, as in fact half the black population of Pensacola and St. Augustine immediately did (they left the country). Some citizens of Leon County, Florida, Florida's most populous and wealthiest county, which wealth was because Leon County had more slaves than any other county in Florida, petitioned the General Assembly to have all free negroes removed from the state. Legislation passed in 1847 required all free Negroes to have a white person as legal guardian; in 1855, an act was passed which prevented free Negroes from entering the state. "In 1861, an act was passed requiring all free Negroes in Florida to register with the judge of probate in whose county they resided. The Negro, when registering, had to give his name, age, color, sex, and occupation, and had to pay one dollar to register.... All Negroes over twelve years of age had to have a guardian approved by the probate judge.... The guardian could be sued for any crime committed by the Negro; the Negro could not be sued. Under the new law, any free Negro or mulatto who did not register with the nearest probate judge was classified as a slave and became the lawful property of any white person who claimed possession."

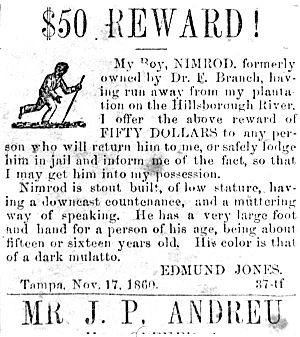

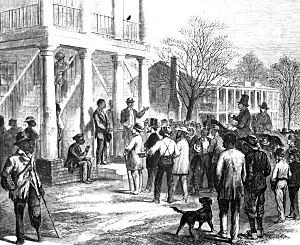

The growth of plantations

American settlers began to establish cotton plantations in northern Florida, which required numerous laborers, which they supplied by buying slaves in the domestic market. On March 3, 1845, Florida became a slave state of the United States. Almost half the state's population were enslaved African Americans working on large cotton and sugar plantations, between the Apalachicola and Suwannee Rivers in the north-central part of the state. Like the people who owned them, many slaves had come from the coastal areas of Georgia and The Carolinas; they were part of the Gullah-Geechee culture of the South Carolina Lowcountry. Others were enslaved African Americans from the Upper South, who had been sold to traders taking slaves to the Deep South. By 1860, Florida had 140,424 people, of whom 44% were enslaved, and fewer than 1,000 free people of color. Their labor accounted for 85% of the state's cotton production. The 1860 Census also indicated that in Leon County, which was the center both of the Florida slave trade and of their plantation industry (see Plantations of Leon County), slaves constituted 73% of the population. As elsewhere, their value was greater than all the land of the county. (References in History of Tallahassee, Florida#Black history.)

Secession

In January 1861, nearly all delegates in the Florida Legislature approved an ordinance of secession, declaring Florida to be "a sovereign and independent nation"—an apparent reassertion to the preamble in Florida's Constitution of 1838, in which Florida agreed with Congress to be a "Free and Independent State." According to William C. Davis, "protection of slavery" was "the explicit reason" for Florida's declaring of secession, as well as the creation of the Confederacy itself.

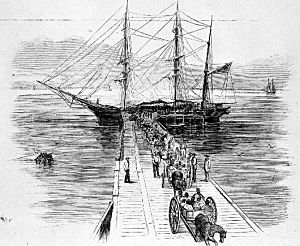

Confederate authorities used slaves as teamsters to transport supplies and as laborers in salt works and fisheries. Many Florida slaves working in these coastal industries escaped to the relative safety of Union-controlled enclaves during the American Civil War. Beginning in 1862, Union military activity in East and West Florida encouraged slaves in plantation areas to flee their owners in search of freedom. Some worked on Union ships and, beginning in 1863, with the Emancipation Proclamation, more than a thousand enlisted as soldiers and sailors in the United States Colored Troops of the military.

Escaped and freed slaves provided Union commanders with valuable intelligence about Confederate troop movements. They also passed back news of Union advances to the men and women who remained enslaved in Confederate-controlled Florida. Planter fears of slave uprisings increased as the war went on.

In May 1865, Federal control was re-established, and slavery abolished.