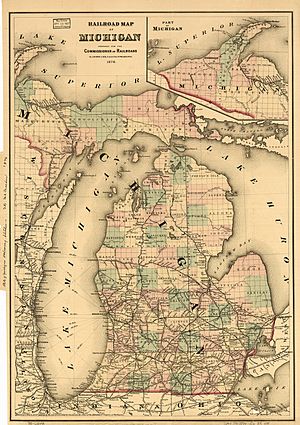

History of railroads in Michigan facts for kids

Railroads have been vital in the history of the population and trade of rough and finished goods in the state of Michigan. While some coastal settlements had previously existed, the population, commercial, and industrial growth of the state further bloomed with the establishment of the railroad.

The state's proximity to Ontario, Canada, aided the transport of goods in a smooth east–west trajectory from the eastern shore of Lake Michigan toward Montreal and Quebec.

Major railroads in the state, prior to 20th century consolidations, had been the Michigan Central Railroad and the New York Central Railroad.

Contents

Chronology

The first roads

The history of railroading in Michigan began in 1830, seven years before the territory became a state, with the chartering of the Pontiac and Detroit Railway. This was the first such charter granted in the Northwest Territory, and occurred the same year the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad began operation. Joining the P&D in 1832 was the Detroit and St. Joseph Railroad, which aimed to cross the entire Lower Peninsula and establish a connection with Lake Michigan on the St. Joseph River. Neither of these projects had made any progress when in 1833 the Michigan Territorial Council granted a charter to yet another company, the Erie and Kalamazoo Railroad.

The Erie & Kalamazoo was to connect Port Lawrence (now Toledo, Ohio) on Lake Erie to some point on the Kalamazoo River, which flows into Lake Michigan. By November 2, 1836, the E&K had completed a 32.8-mile (52.8 km) line from Port Lawrence northeast to Adrian, Michigan, in Lenawee County. Horse teams drew a solitary car along the line, the first railroad trip undertaken west of the state of New York. The first steam locomotives operated in early 1837, with an average speed of 10 miles per hour (16 km/h).

Further north, the Detroit and Pontiac Railroad had completed a 12.3-mile (19.8 km) line from Detroit north to Royal Oak. Operations began in 1838 but would be horse-drawn until the following year. After financial difficulties and government entanglements the railroad reached Pontiac in 1843, for a total length of 26.6 miles (42.8 km).

The state fiasco

By 1837 Michigan had the beginnings of a railroad network, but one with which both the government and the people were dissatisfied. In the first seven years of railroading in Michigan (1830–1837) the Michigan Territorial Council approved charters for twenty-three private railroad companies. Of these, only five completed and opened lines, and then for a total in-state (excluding Ohio) length of only 61.1 miles (98.3 km). The two main lines, the Erie & Kalamazoo (Toledo–Adrian) and the Detroit & Pontiac (Detroit–Royal Oak) reflected the needs of the local business interests which built them and were inadequate from the perspective of the newly organized state government. Additionally, the settlement of the Toledo War placed Toledo in Ohio, which meant that the one railroad-connected port on Lake Erie lay in a different state. Therefore, using the state of New York's construction of the Erie Canal as a model, Michigan embarked on an ambitious project to construct three railroad lines across the state.

Michigan's project was not unusual at the time: her neighbors Illinois, Indiana and Ohio all had either government-funded building programs or generous assistance packages for private companies. Michigan lawmakers proposed to build three lines from the east side of the state to locations on Lake Michigan:

- The "Northern" line: St. Clair (on the St. Clair River which separates Michigan from the Canadian province of Ontario) to Grand Haven.

- The "Central" line: Detroit to St. Joseph.

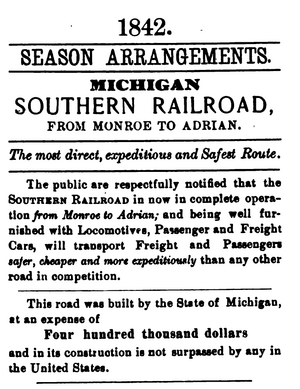

- The "Southern" line: Monroe (on Lake Erie) to New Buffalo.

The Central line would connect with the D&P in Detroit, while the Southern line would connect with the E&K near Adrian. The government, under the leadership of Governor Stevens T. Mason, would finance the whole project through a US$5 million loan. A report prepared by a legislative committee predicted that construction of all three lines would take no more than five years, that revenues earned from the partially completed lines would be sufficient to satisfy interest payments during that period, and that once all three railroads were in full operation revenues earned would permit the state to pay off the loan in 20 years and turn a substantial profit. These assumptions proved to be wildly optimistic, leading to what one historian termed a "fiasco" and another an "embarrassment."

Michigan's attempt to secure the loan coincided with the Panic of 1837: banks failed, sales of land dried up, and money was hard to obtain. The construction of the lines was bedeviled by competition between local interests, all of whom wanted to benefit from the state project. An investigation into the management of the project found instances of graft and extravagance and a general inefficiency. At the end of 1845 the state had spent some US$4 million; the "Southern" line had reached Hillsdale and the "Central" Battle Creek, while the "Northern" still existed on paper only. Altogether only 187.9 miles (302.4 km) of a projected 600 miles (970 km)-plus were in operation, and the state's finances were in chaos. In 1846 the legislature sold both the "Southern" and "Central" lines to private investors at a loss; out of the ruins of the state's projects arose the Michigan Southern Railroad and Michigan Central Railroad. Another outcome was Michigan's revised constitution of 1850, which explicitly forbade direct investment in or construction of "any work of internal improvement."

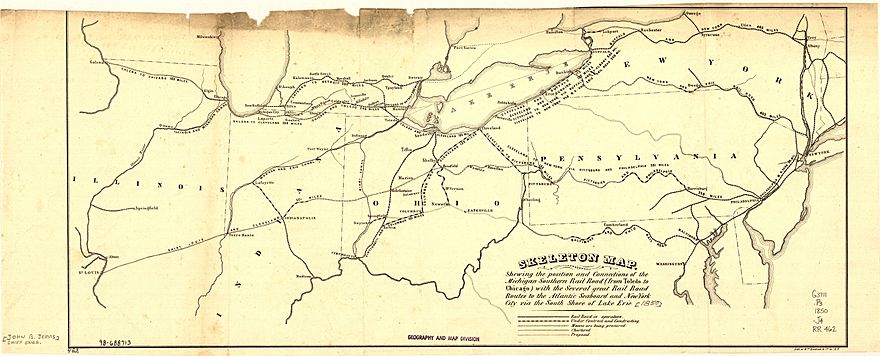

Across the Lower Peninsula

Among other requirements, that state in its sale of the "Central" and "Southern" lines stipulated that both companies complete their lines to points on the coast of Lake Michigan. The Michigan Central then stood at Kalamazoo, on the Kalamazoo River, while the Michigan Southern stood at Hillsdale, far to the east. Racing ahead of the legislature's requirement, both companies sensed the growing importance of Chicago, Illinois, a port city on the southwest coast of Lake Michigan at the mouth of the Chicago River, which flowed into the Mississippi. The Central turned its line south toward New Buffalo, a small town close to the Michigan/Indiana border, while the Southern, after some negotiating with the state, bypassed Lake Michigan altogether and dropped south into Indiana, passing through Sturgis and on into South Bend, Indiana. On February 20, 1852, the Southern became the first Michigan company to run trains into Chicago, via an operating agreement with the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad. The Central followed suit three months later, via its own arrangement with the Illinois Central Railroad.

Capitalizing on Jackson's central location, Michigan Central Railroad added the growing community as its eastern terminus in 1841. With the addition of the railroad, Jackson began its development as an important rail center. By 1871 Jackson was recognized as an important rail center with six different railroads passing through the city. By 1910, Jackson was home to switching and repair headquarters for 10 railroads.

The third line to cross the Lower Peninsula grew out of the Detroit & Pontiac (D&P), which had emerged from bankruptcy in 1849 with a new set of backers and fresh capital. Under the new name of the Detroit & Milwaukee (D&M), the railroad pushed across the central part of the peninsula, eventually reaching Grand Haven on the shores of Lake Michigan on November 22, 1858. From Detroit through Grand Rapids to Grand Haven the line stretched 186 miles (299 km). While similar to the projected northern line, it ignored St. Clair in favor of a Detroit terminus.

Winfield Scott Gerrish is credited with revolutionizing lumbering in Michigan by building a seven-mile-long logging railroad from Lake George to the Muskegon River in Clare County in 1877.

Land grants and mining roads

The third great burst in railroad activity in the state of Michigan was fueled by the institution of a land grant program by the federal government. Under an act of 1856 and successive acts Michigan had in its gift over 5,000,000 acres (20,000 km2) of land which could be given to railroads (which would then re-sell these lands for a profit) in exchange for constructing certain routes. The designated routes were removed from the existing railway network, which with minor exceptions criss-crossed the southern Lower Peninsula.

| Location | End points | Railroad | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western Upper Peninsula | Marquette—Ontonagon | Duluth, South Shore and Atlantic Railway | |

| Western Upper Peninsula | Ontonagon—Wisconsin state line | Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway | |

| Western Upper Peninsula | Marquette—Little Bay de Noc | Chicago and North Western Railway | |

| Lower Peninsula | Fort Wayne, Indiana—Straits of Mackinac | Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad | |

| Lower Peninsula | Amboy, Indiana—Lansing—Traverse Bay | Michigan Central Railroad and Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway | LS&MS took ownership |

| Central Lower Peninsula | Flint—Grand Haven | Detroit and Milwaukee Railroad | |

| Central Lower Peninsula | Flint—Pere Marquette | Flint and Pere Marquette Railroad | "Pere Marquette" is now Ludington |

The proposed lines would cover several gaps in Michigan's growing railroad network: fully half the land grants would go to railroads in the Upper Peninsula, where substantial mineral resources had been discovered, while two routes in the Lower Peninsula would run north-south, bisecting the existing cross-state routes.

Even with the land grants, railroad construction remained a difficult prospect. The availability of the grants did not guarantee financial success; John Murray Forbes, a major backer of the Michigan Central, considered them irrelevant compared to the intelligence of the railroad's management. The Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad (GR&I) faced serious difficulties in raising capital, and it was only through the intervention of the Pennsylvania Railroad (via its subsidiary the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railway) that the GR&I finished enough of its planned route to save its charter. Even then, the railroad entered foreclosure in 1895. The Flint and Pere Marquette Railroad (F&PM) initially eschewed its land grants and built south from East Saginaw to link up with the Detroit & Milwaukee, over whose lines it ran trains into Detroit. The first company to attempt the Amboy–Traverse Bay line, the Amboy, Lansing and Traverse Bay Railroad, failed after completing a short line between Lansing and Owosso, and was eventually split between the LS&MS and the Michigan Central.

In the sparsely-populated Upper Peninsula railroad development revolved around the need to transport copper and iron ore from the resource-rich mountain ranges in the western part of the state to Chicago, Illinois, either through the state of Wisconsin or on the broad highway of Lake Michigan. The first railroad in the UP, the Iron Mountain Railroad, preceded the land grants and was built by private funds between 1851 and 1857. With the assistance of land grants, traffic in the hills came to be dominated by three companies whose primary base was out of state: the Duluth, South Shore and Atlantic Railway, the Chicago and North Western Transportation Company and the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (the "Milwaukee Road"). In the east, the Detroit, Mackinac and Marquette Railroad completed a line from Marquette to St. Ignace on the north side of the Straits of Mackinac, nominally linking the state's two peninsulas.

Boom and bust

The decades after the Civil War witnessed a massive expansion of Michigan's railroad network: in 1865 the state possessed roughly 1,000 miles (1,600 km) of track; by 1890 it had 9,000 miles (14,000 km). These new lines were built by private companies and financed by a mixture of borrowed money, stock sales and, for a time, aid from local governments. During what one historian called "southern Michigan's railroad mania" many lines were built without a true appreciation of potential profitability, resulting in a financial landscape littered with bankruptcies and companies in receivership.

Railroads in Michigan today

Railroads continue to operate in the state of Michigan, although at a reduced level. Michigan is served by 4 Class I railroads: the Canadian National Railway, the Canadian Pacific Railway, CSX Transportation, and Norfolk Southern Railway. These are augmented by several dozen short line railroads. The vast majority of rail service in Michigan is devoted to freight, with Amtrak and various scenic railroads the exceptions.

Intercity passenger service

There is Amtrak passenger rail service in the state, connecting the cities of Detroit, Ann Arbor, East Lansing, Grand Rapids, Jackson, Battle Creek, Kalamazoo, Flint, and Port Huron to Chicago, Illinois. The three routes taken together carried 664,284 passengers for revenues of $20.3 million during fiscal year 2005-2006, a record.

The Pere Marquette and Blue Water services receive funding from the State of Michigan. For fiscal year 2005-2006 this was $7.1 million. Because of improving revenues and patronage over the past year, the contract for FY 2006-2007 is for $6.2 million. The Detroit-Chicago corridor has been designated by the Federal Railroad Administration as a high-speed rail corridor. A 97-mile (156 km) stretch along the route of Blue Water and Wolverine from Porter, Indiana to Kalamazoo, Michigan is the longest segment of track owned by Amtrak outside of the Northeast Corridor. Amtrak began incremental speed increases along this stretch in January 2002. By 2012, trains were regularly running at the planned top speed of 110 miles per hour (180 km/h) between Porter and Kalamazoo.

Commuter service

Michigan has not had commuter rail service since 1984, when Amtrak discontinued the Michigan Executive, which ran between Ann Arbor and Detroit. SEMTA had discontinued the Grand Trunk Western's old Pontiac–Detroit service the year before.

There are currently two new proposed systems under consideration. WALLY, which is backed by the Great Lakes Central Railroad and a coalition of Washtenaw County agencies and businesses, would provide daily service between Ann Arbor and Howell. The other, a proposed project by the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments, would provide daily service between Detroit and Ann Arbor with stops in Ypsilanti, Detroit Metro Airport, and Dearborn. Recent discussions have included possible extension of the project to Jackson.

Station architecture

Images for kids

-

Detroit's Michigan Central Station, built in 1913, is a prominent example of the beaux arts style