History of nursing in the United States facts for kids

The history of nursing in the United States focuses on the professionalization of Nursing in the United States since the Civil War.

Contents

Origins

Before the 1870s "women working in North American urban hospitals typically were untrained, working class, and accorded lowly status by both the medical profession ...and society at large". Nursing had the much the same lowly status in Europe. However D'Antonio shows that in the mid-19th century nursing was transformed from a domestic duty of caring for members of one's extended family, to a regular job performed for a cash wage. Nurses were now hired by strangers to care for sick family members at home. These changes were made possible by the realization that expertise mattered more than kinship, as physicians recommended nurses they trusted. By the 1880s home care nursing was the usual career path after graduation from the hospital-based nursing school.

Civil War

During the American Civil War (1861–65), the United States Sanitary Commission, a federal civilian agency, handled most of the medical and nursing care of the Union armies, together with necessary acquisition and transportation of medical supplies. Dorothea Dix, serving as the Commission's Superintendent, convinced the medical corps of the value of women working in 350 Commission or Army hospitals. In both the North and South, over 20,000 women volunteered to work in hospitals, usually in nursing care. They assisted surgeons during procedures, administered medicines, supervised the feedings of patients, and cleaned bedding and clothes. They gave good cheer, wrote letters the patients dictated, and comforted the dying. A representative nurse was Helen L. Gilson (1835–68) of Chelsea, Massachusetts, who served in Sanitary Commission. She supervised supplies, dressed wounds, and cooked special foods for patients on a limited diet. She worked in hospitals after the battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg. She was a successful administrator, especially at the hospital for black soldiers at City Point, Virginia. The middle-class women North and South who volunteered provided vitally needed nursing services and were rewarded with a sense of patriotism and civic duty in addition to opportunity to demonstrate their skills and gain new ones, while receiving wages and sharing the hardships of the men.

Mary Livermore, Mary Ann Bickerdyke, and Annie Wittenmeyer played leadership roles. After the war, some nurses wrote memoirs of their experiences; examples include Dix, Livermore, Sarah Palmer Young, and Sarah Emma Edmonds. Clara Barton (1821-1912) gained fame for her nursing work during the American Civil War. She was an energetic organizer who established the American Red Cross, which was primarily a disaster relief agency, but which also supported nursing programs.

Several thousand women were just as active in nursing in the Confederacy, but were less well organized and faced severe shortages of supplies and a much weaker system of 150 hospitals. Nursing and vital support services were provided not only by matrons and nurses, but also by local volunteers, slaves, free blacks, and prisoners of war.

Professionalization

Nursing professionalized rapidly in the late 19th century following the British model as larger hospitals set up nursing schools that attracted ambitious women from middle- and working-class backgrounds. Agnes Elizabeth Jones and Linda Richards established quality nursing schools in the U.S. and Japan. Richards was officially America's first professionally trained nurse, graduating in 1873 from the New England Hospital for Women and Children in Boston. Hospital nursing schools in the United States and Canada took the lead in applying Nightingale's model to their training programs. For example, Isabel Hampton Robb (1860–1910), as director of the new Johns Hopkins Hospital Training School for Nurses, deliberately set out to use advanced training to upgrade the social status of nursing to a middle class career, instead of a low pay, low status, long hours, and heavy work job for working-class women.

After 1880, standards of classroom and on-the-job training rose, as did standards of professional conduct. For textbooks, many schools used: A Manual of Training (1878); A Hand-Book of Nursing for Family and General Use (1878); A Text-Book of Nursing for the Use of Training Schools, Families, and Private Students (1885); and Nursing: Its Principles and Practice for Hospital and Private Use (1893). These books defined the curriculum of the new nursing schools and introduced nurses to modern medical science and scientific thinking.

In the early 1900s, the autonomous, nursing-controlled, Nightingale-era schools came to an end. Schools became controlled by hospitals, and formal "book learning" was discouraged in favor of clinical experience. Hospitals used student nurses as cheap labor. In the late 1920s, the women's specialties in health care included 294,000 trained nurses, 150,000 untrained nurses, 47,000 midwives, and 550,000 other hospital workers (most of them women).

Sandelowski finds that by 1900 physicians were allowing nurses to routinely use the thermometer and stethoscope, and in some cases even the new X-ray machines, microscopes and laboratory testing tools. For the first time, nurses could supplement their subjective observations with scientific tools. Most nurses remained at the bedside, where they used the new technology to gather information for doctors, but were not allowed to make a medical diagnosis. Their bond with the patient remained their primary role.

The John Sealy Hospital Training School for Nurses opened in 1890 in Galveston, Texas. It grew rapidly and in 1896 became the School of Nursing, University of Texas; it was the first nursing school to become part of a university in the state of Texas. In recent decades, professionalization has moved nursing degrees out of RN-oriented hospital schools and into community colleges and universities. Specialization has brought numerous journals to broaden the knowledge base of the profession. Very few blacks attended universities with nursing schools. The solution was found by the Rockefeller's General Education Board, which funded new nursing schools headed by Rita E. Miller at Dillard University in New Orleans (1942) and by Mary Elizabeth Lancaster Carnegie at Florida A. & M. College in Tallahassee (1945).

Hospitals

The number of hospitals grew from 149 in 1873 to 4,400 in 1910 (with 420,000 beds) to 6,300 in 1933, primarily because the public had more trust in hospitals and could afford to pay for more intensive and professional care. Most larger hospitals operated a school of nursing, which provided training to young women, who in turn worked without pay. The number of active graduate nurses rose rapidly from 51,000 in 1910 to 375,000 in 1940 and 700,000 in 1970.

They were operated by city, state and federal agencies, by churches, by stand-alone non-profits, and by for-profit enterprises run by a local doctor.

Religious hospitals

All major religious denominations in the United States built hospitals staffed by primarily by unpaid student nurses supervised by some graduate nurses.

In 1915, the Catholic Church ran 541 hospitals, staffed primarily by unpaid nuns.

The Lutheran and Episcopal churches entered the health field, especially by setting up orders of women, called deaconesses who dedicated themselves to nursing services. The modern deaconess movement began in Germany in 1836. William Passavant in 1849 brought the first four deaconesses to Pittsburgh, in the United States, after visiting Kaiserswerth. They worked at the Pittsburgh Infirmary (now Passavant Hospital).

American Methodists—the largest Protestant denomination in the country—engaged in large-scale missionary activity in Asia and elsewhere in the world, making medical services a priority as early as the 1850s. Methodists in America took note, and began opening their own charitable institutions such as orphanages and homes for the elderly after 1860. In the 1880s, Methodists began opening hospitals in the United States, which served people of all religious backgrounds. By 1895, 13 Methodist hospitals were in operation in major cities.

In 1884, U.S. Lutherans, particularly John D. Lankenau, brought seven sisters from Germany to run the German Hospital in Philadelphia.

By 1963, the Lutheran Church in America had centers for deaconess work in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Omaha.

Public health

Public health nursing after 1900 offered a new career for professional nurses in addition to private duty work. The role of public health nurse began in Los Angeles in 1898, and by 1924, there were 12,000 public health nurses, half of them in America's 100 largest cities. Their average annual salary of public health nurses in larger cities was $1390. In addition, there were thousands of nurses employed by private agencies handling similar work. Public health nurses supervised health issues in the public and parochial schools, to prenatal and infant care, handled communicable diseases such as tuberculosis, and dealt with an aerial diseases.

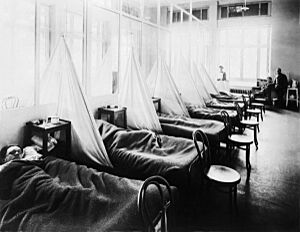

Historian Nancy Bristow has argued that the great 1918 flu pandemic contributed to the success of women in the field of nursing. This was due in part to the failure of medical doctors, who were predominantly men, to contain and prevent the illness. Nursing staff, who were predominantly women, felt more inclined to celebrate the success of their patient care and less inclined to identify the spread of the disease with their own work.

During the Great Depression, federal relief agencies funded many large-scale public health programs in every state, some of which became permanent. The programs expanding job opportunities for nurses, especially the private duty RNs who suffered high unemployment rates.

In the United States, a representative public health worker was Dr. Sara Josephine Baker who established many programs to help the poor in New York City keep their infants healthy, leading teams of nurses into the crowded neighborhoods of Hell's Kitchen and teaching mothers how to dress, feed, and bathe their babies.

The federal Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) operated a large-scale field nursing program. Field nurses targeted native women for health education, emphasizing personal hygiene, and infant care and nutrition.

Military nursing

During the Spanish–American War of 1898, medical conditions in the tropical war zone were dangerous, with yellow fever and malaria endemic and deadly. The United States government called for women to volunteer as nurses. The Daughters of the American Revolution and other organizations helped thousands of women to sign up as nurses, but few were professionally trained. Among the latter were 250 Catholic nurses, most of them from the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. The Army hired female civilian nurses to help with the wounded. Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee was put in charge of selecting contract nurses to work as civilians with the U.S. Army. In all, more than 1,500 women nurses worked as contract nurses during the Spanish—American War.

Professionalization was a dominant theme during the Progressive Era, because it valued expertise and hierarchy over ad hoc volunteering in the name of civic duty. Congress consequently established the Army Nurse Corps in 1901 and the Navy Nurse Corps in 1908. The Red Cross became a quasi-official federal agency in 1905 and its American Red Cross Nursing Service took upon itself primary responsibility for recruiting and assigning nurses.

During World War I, from 1917 to 1918, the military recruited 20,000 registered nurses (all women) for military and navy duty in 58 military hospitals; they helped staff 47 ambulance companies that operated on the Western Front. More than 10,000 served overseas, while 5,400 nurses enrolled in the Army's new School of Nursing. Key decisions were made by Jane Delano, director of the Red Cross Nursing Service, Mary Adelaide Nutting, president of the American Federation of Nurses, and Annie Warburton Goodrich, dean of the Army School of Nursing. Delano proposed training aides to cover the shortage of nurses, but Nutting and Goodrich were strongly opposed, arguing that aides devalued nursing as a profession and would undermine their goal of advancing nursing education at the college level. The compromise was to establish the Army School of Nursing, which operated from 1919 to 1939.

The nurses—all of whom were women—were kept far from the front lines, and although none were killed by enemy action, more than 200 died from disease, especially the Spanish flu epidemic. Demobilization reduced the Army and Navy corps to skeleton units designed to be expanded should a new war take place. Eligibility at this time included being female, white, unmarried, volunteer, and a graduate from a civilian nursing school. In 1920, Army Nurse Corps personnel received officer-equivalent ranks and wore Army rank insignia on their uniforms. However, they did not receive equivalent pay and were not considered part of the US Army.

American Nurses Association

In 1901 the American Society of Superintendents of Training Schools for Nurses and the Nurses' Associated Alumnae of the United States and Canada merged to form the American Federation of Nurses. It joined the National Council of Women and the International Council of Nurses. The federation was replaced in 1911 by the new American Nurses' Association.

The United American Nurses (UAN) was a trade union affiliated with the AFL–CIO. Founded in 1999, it only represented registered nurses (RNs). In 2009, UAN merged with the California Nurses Association/National Nurses Organizing Committee and Massachusetts Nurses Association to form National Nurses United.

World War II

As Campbell (1984) shows, the nursing profession was transformed by World War II. Army and Navy nursing was highly attractive and 30% volunteered for duty—a larger proportion than any other occupation in American society. The 59,000 women of the Army Nurse Corps and the 18,000 of the Navy Nurse Corps at first were selected by the civilian men of the Red Cross. No men were allowed in. But as the nurses rose in rank they took more control and by 1944 were autonomous of the Red Cross. As veterans, they took increasing control of the profession through the ANA. As the Air Force became virtually independent of the Army, so too did the United States Air Force Nurse Corps.

The services built a very large network of hospitals, and used hundreds of thousands of enlisted men (tens of thousands of enlisted women) as nurses' aides. Congress set up a major new program, the Cadet Nurse Corps, that funded nursing schools to train 124,000 young civilian women (including 3,000 blacks). The plan was to encourage graduates to join the nurse corps of the Army or Navy, but that was dropped when the war ended in 1945 before the first cadets graduated.

The public image of the nurses was highly favorable during the war, as the simplified by such Hollywood films as Cry 'Havoc' (1943) which portrayed nurses as selfless heroes under enemy fire. Some nurses were captured by the Japanese, but in practice they were largely kept out of harm's way, with the great majority stationed on the home front. However, 77 were stationed in the jungles of the Pacific, where their uniform consisted of "khaki slacks, mud, shirts, mud, field shoes, mud, and fatigues." The medical services were large operations, with over 600,000 soldiers, and ten enlisted men for every nurse. Nearly all the doctors were men, with women doctors allowed only to examine the WAC.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt hailed the service of nurses in the war effort in his final "Fireside Chat" of January 6, 1945. Expecting heavy casualties in the invasion of Japan, he called for a compulsory draft of nurses. The casualties never happened and there was never a draft of American nurses.

Postwar transformation

Tensions of long standing had pulled nursing in two directions, as Campbell explains:

Nursing enjoyed a great humanitarian tradition and clearly attracted so many women because of its goal of helping sick people. On the other hand, the remarkable advances in medical science and technology and in the organizing, financing, and delivery of patient care had wrought radical transformations since the days of Nightingale and Barton. Nursing was poised to become a technological field that required extensive training, far more than was usually available. Should nurses be technicians or humanitarians?

Before the war the nurses were too weak to resolve the tension. Nurses in hospital service and public health were controlled by physicians; those in private practice operated as individuals and had no collective power. The war changed everything; nurses ran the nurse corps and as officers they had senior administrative roles over major operations. They commanded hundreds of thousands of men (as well as Wacs and WAVES) who worked in the wards. They learned how power works. After the war they took control of the ANA; they dispensed with control by the Red Cross. The women who had served in field and evacuation hospitals Europe and the South Pacific ignored the older traditionalists who resented the superior skills and command presence of the new generation. They had "become accustomed to taking the initiative, making quick decisions, and adopting innovative solutions to a broad range of medical-related problems." They used the prestige of their profession to chart their own course.

The American Nurses Association became the premier organization. It integrated racially, absorbing the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses in 1951. Male nurses, however, remained outsiders and were kept out of nursing schools. The Red Cross lost its central role in supplying military nurses. The National Nursing Council was disbanded, as was the Procurement and Assignment Service of the War Manpower Convention. The Cadet Nurse Corps closed in 1948. The ANA campaigned for better pay and working conditions, for in 1946, the average RN earned about one dollar an hour—or $175 a month, ranging from $153 for private duty nurses to $207 for nurse educators. The hospital system fought back, and secured an exemption from the National Labor Relations Act that made unionization very difficult. They National Organization of Hospital Schools of Nursing launched a last-ditch fight to stop the movement of all nursing education into universities.

Private duty nursing rapidly declined after the Great Depression of 1929-39 lowered family incomes. Hospitals increasingly handled the round-the-clock care of sick people for they had the staff, the expertise and the equipment to treat them. Furthermore, hospitals were more efficient and cheaper than private duty nurses who cared for one patient at a time. Nursing students spent their time mostly studying. To replace their work, hospitals hired graduate nurses who had finished their training and wanted permanent careers, as well as lower-paid aides, attendants and practical nurses who handled many chores. In 1946, the nation's hospitals employed 178,000 nursing auxiliaries; six years later they employed 297,000. The new staff allowed the proportion of hospital patient care provided by RNs to fall from 75% to 30%.

Since 1964

The Nurse Training Act of 1964 transformed the education of nursing, moving the locale from hospitals to universities and community colleges. There was a sharp increase in the number of nurses; not only did the supply increase, but more women remained in the profession after marrying. Salaries increased, as did specialization and the growth of administrative roles for nurses in both the academic and hospital environments. Private duty nursing, once the mainstay for older RNs, became less prevalent. D'Antonio traces the history over six decades of a cohort of nurses who graduated in 1919, going back and forth between paid employment and housework.

From 1965 through 1988, a surge of 70,000 trained nurses immigrated to the U.S. for jobs that paid much better than those in their home countries. Most were from Asia. The Philippines had strong connections with American nursing since 1898 and after World War II adopted a national policy to train and export highly skilled nurses across the globe to bolster the Philippine economy. The number of Philippine nursing schools soared from 17 in 1950 to 140 in 1970, together with a stress on building English language proficiency. The new arrivals organized and formed local groups that merged into the National Federation of Philippines Nurses Associations in the United States.

As of 2013, the nursing profession remained overwhelmingly female, but the representation of men has increased as the demand for nurses has grown over the last several decades, according to a U.S. Census Bureau study. The proportion of male licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses has more than doubled from 3.9 percent to 8.1 percent. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 12% of registered nurses in 2019 were men, up from 2.7% male registered nurses in 1970.

As outlined in recommendations from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, nurses have a high rate of workplace injury, mainly when lifting patients. The agency recommends eliminating manual lifting in favor of mechanized devices, and in 2015, began an enforcement campaign to force hospitals to do so.

In 1998, nurse Fannie Gaston-Johansson became the first African American woman tenured full professor at Johns Hopkins University.

See also

- History of medicine in the United States

- Medicine in the American Civil War

- History of Philippine nurses in the United States

- History of nursing

- Nursing in Canada#History