History of money facts for kids

The history of money concerns the development throughout time of systems that provide the functions of money. Such systems can be understood as means of trading wealth indirectly; not directly as with bartering (exchanging). Money is a mechanism that facilitates this process.

Money may take a physical form as in coins and notes, or may exist as a written or electronic account.

Early history

The invention of money took place before the beginning of written history.

Many things in ancient markets could be described as a medium of exchange. These included livestock and grain, cowrie shells or beads that were exchanged for more useful commodities. However, such exchanges would be better described as barter.

Due to the complexities of ancient history, it is impossible to trace the true origin of the invention of money. Evidence in the histories supports the idea that money has taken two main forms: money of account (debits and credits on ledgers) and money of exchange (tangible media of exchange made from clay, leather, paper, bamboo, metal, etc.).

In the ancient empires of Egypt, Babylon, India and China, the temples and palaces often had commodity warehouses which made use of clay tokens and other materials which served as evidence of a claim upon a portion of the goods stored in the warehouses. There isn't any concrete evidence these kinds of tokens were used for trade, however, only for administration and accounting.

While not the oldest form of money of exchange, various metals (both common and precious metals) were also used. The Romans' use of bronze, while not among the more ancient examples, is well-documented. First, the "aes rude" (rough bronze) was used. The aes grave (heavy bronze) (or As) is the start of the use of coins in Rome, but not the oldest known example of metal coinage.

Coins

Gold and silver have been the most common forms of money throughout history. In many languages, such as Spanish, French, Hebrew and Italian, the word for silver is still directly related to the word for money. Sometimes other metals were used. For instance, Ancient Sparta minted coins from iron to discourage its citizens from engaging in foreign trade. In the early 17th century Sweden lacked precious metals, and so produced "plate money": large slabs of copper 50 cm or more in length and width, stamped with indications of their value.

Gold coins began to be minted again in Europe in the 13th century. Frederick II is credited with having reintroduced gold coins during the Crusades. During the 14th century Europe changed from use of silver in currency to minting of gold. Vienna made this change in 1328.

Metal-based coins had the advantage of carrying their value within the coins themselves. On the other hand, they induced manipulations, such as the clipping of coins to remove some of the precious metal.

A greater problem was the simultaneous co-existence of gold, silver and copper coins in Europe. For instance, the gold guinea coin began to rise against the silver crown in England in the 1670s and 1680s. Stability came when national banks guaranteed to change silver money into gold at a fixed rate

Another step in the evolution of money was the change from a coin being a unit of weight to being a unit of value.

First paper money

Paper money was introduced in Song dynasty China during the 11th century. The development of the banknote began in the seventh century. By the early 12th century, the amount of banknotes issued in a single year amounted to an annual rate of 26 million strings of cash coins.

In the 13th century, paper money became known in Europe through the accounts of travelers, such as Marco Polo and William of Rubruck. Marco Polo's account of paper money during the Yuan dynasty is the subject of a chapter of his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, titled "How the Great Kaan Causeth the Bark of Trees, Made into Something Like Paper, to Pass for Money All Over his Country."

First European banknotes

The first European banknotes were issued by Stockholms Banco, a predecessor of Sweden's central bank Sveriges Riksbank, in 1661. These replaced the copper-plates being used instead as a means of payment.

Banks began issuing paper notes quite properly termed "banknotes", which circulated in the same way that government-issued currency circulates today. In England this practice continued up to 1694. Scottish banks continued issuing notes until 1850, and still do issue banknotes backed by Bank of England notes. In the United States, this practice continued through the 19th century; at one time there were more than 5,000 different types of banknotes issued by various commercial banks in America. Only the notes issued by the largest, most creditworthy banks were widely accepted. The scrip of smaller, lesser-known institutions circulated locally. Farther from home it was only accepted at a discounted rate, if at all.

These banknotes were a form of representative money which could be converted into gold or silver by application at the bank.

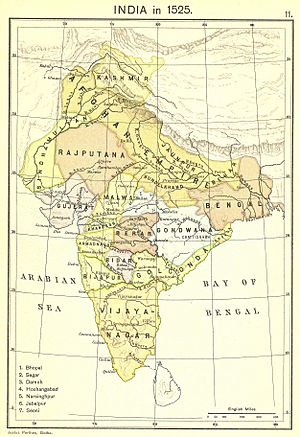

In India the earliest paper money was issued by Bank of Hindostan (1770– 1832), General Bank of Bengal and Bihar (1773–75), and Bengal Bank (1784–91).

The use of banknotes issued by private commercial banks has gradually been replaced by the issuance of bank notes authorized and controlled by national governments. The Bank of England was granted sole rights to issue banknotes in England after 1694. In the United States, the Federal Reserve Bank was granted similar rights after its establishment in 1913. Until recently, these government-authorized currencies were forms of representative money, since they were partially backed by gold or silver and were theoretically convertible into gold or silver.

In 1971, United States President Richard Nixon announced that the US dollar would not be directly convertible to Gold anymore. Since then, the US dollar, and thus all national currencies, are free-floating currencies.

Payment cards

In the late 20th century, payment cards such as credit cards and debit cards became the dominant mode of consumer payment in the First World. The Bankamericard, launched in 1958, became the first third-party credit card to acquire widespread use and be accepted in shops and stores all over the United States, soon followed by the Mastercard and the American Express. Since 1980, Credit Card companies are exempt from state usury laws, and so can charge any interest rate they see fit. Outside America, other payment cards became more popular than credit cards, such as France's Carte Bleue.

Digital currency

The development of computer technology in the second part of the twentieth century allowed money to be represented digitally. By 1990, in the United States, all money transferred between its central bank and commercial banks was in electronic form. By the 2000s most money existed as digital currency in banks databases. In 2012, by number of transaction, 20 to 58 percent of transactions were electronic (dependent on country). The benefit of digital currency is that it allows for easier, faster, and more flexible payments.

Cryptocurrencies

In 2008, Bitcoin was proposed by an unknown author/s under the pseudonym of Satoshi Nakamoto. It was implemented the same year. Its use of cryptography allowed the currency to have a trustless, non-fungible and tamper resistant distributed ledger called a blockchain. It became the first widely used decentralized, peer-to-peer, cryptocurrency. Other comparable systems had been proposed since the 1980s. The protocol proposed by Nakamoto solved what is known as the double-spending problem without the need of a trusted third-party.

Since Bitcoin's inception, thousands of other cryptocurrencies have been introduced.

Images for kids

-

Spade money from the Zhou Dynasty, c. 650–400 BC

See also

In Spanish: Historia del dinero para niños

In Spanish: Historia del dinero para niños