Hassanamisco Nipmuc facts for kids

The Hassanamisco Nipmuc people are part of a larger tribe that identifies itself as the Nipmuc Nation. The Hassanamisco Nipmuc own three and a half acres of reservation land in what is present day Grafton, Massachusetts. This group of indigenous people is native to Central Massachusetts, Northeastern Connecticut, and parts of Rhode Island.

In 1647, a Puritan reverend by the name of John Eliot created the Hassanmesit "praying town." Through the creation and usage of this town, the Nipmuc people were converted to Christianity. In 1727, a Nipmuc woman, Sarah Robins took possession of the land that is currently referred to as the Hassanamisco Reservation. Sarah began the tradition of female inheritance that lasted for generations. In the mid-1600s intermarriages between the Nipmuc people and African Americans became common, whether it be because of bonding over shared marginalization, or because of the dwindling numbers of available Native American men. These marriages most often occurred between Native American women and African American men.

There are nearly 600 members of the Nipmuc tribe living in Massachusetts today. The Hassanamisco Reservation and Cisco Homestead in Grafton, Massachusetts are still owned and used by the Nipmuc people. They remain central to their connection with their history and culture. In 2011, the reservation and homestead were placed on the National Register of Historic Places in an effort to protect the land from leaving native hands. Powwows have been held each year in July at the Hassanamisco Reservation since 1924 and are open to both native and non-native people.

Contents

History

The Nipmuc people, also referred to as "fresh water people," were divided into many villages which were connected through alliances and trade. They once had a vast amount of land and were spread throughout what is now eastern to central Massachusetts and parts of Rhode Island and Connecticut. The people hunted, gathered, and planted food. The women of the tribe were in charge of producing and preparing food for their families and were the ones who passed down cultural knowledge from generation to generation. Since the wetus that they lived in could be moved, they were seen as "wanderers." They took great care of the land on which they lived.

Not much is known about the Nipmuc people before the arrival of European settlers, but when the Pilgrims first arrived in Massachusetts in 1620, there were around 6,000 Nimpuc people. The earliest encounter known was in 1621, when the settlers and the Native Americans were friendly with one another. For example, when the settlers were starving one of the tribe members brought them corn.

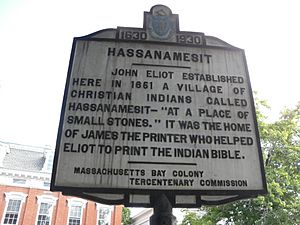

In the mid-1600s, Hassanemesit was one of more than a dozen Praying Towns established by the Massachusetts Bay Colony and Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England as permanent, European-style settlements for Christianized "praying Indians" in efforts to convert Eastern Algonquians to Christianity. In November 1675 during King Philip's War, the praying Indians of Hassanemesit were presented with an ultimatum by surrounding Nipmuc to join their coalition and the town was depopulated for the duration of the war.

After the end of King Phillip's War in the mid seventeenth century, the seven Nipmuc families that returned from war are referred to now as the Hassanamisco Nipmuc people. The Hassanamisco land was sold by settlers without consent. The Nipmuc people were allowed to keep 1,200 acres. That land began to dwindle as some Hassanmesit Nipmuc people started to sell or lease their land to encroaching settlers. It has been theorized that the reasons behind the sale of the land were because of high mortality rates due to participation in wars. From the 1720s to the 1740s, the Colony of Massachusetts put pressure on the Hassanamesit Nipmuc to sell their land and enter the market economy. However, this was often a tactic used on Native Americans so that they would get trapped into debt and then the settlers could claim their land as payment. The Hassanmesit Nipmuc fell victim to this practice and sold some communal land. Their land continued to be sold in pieces until 1857 when Moses Printer sold his land to a man names Harry Arnold. Ever since the remaining acres have been Nipmuc land and is currently known as the Hassanamisco Reservation.

Sarah Robins was a member of one of the original seven Nipmuc families. Sarah took possession of the land in 1727 and began a tradition of female land inheritance that lasted for hundreds of years. The female members of the Cisco family took control over the land in the late nineteenth century. These women became the caretakers of the land, working to ensure its preservation. After 1857, Sarah Arnold Cisco's land became the last original piece of Nipmuc land dating back to before the 1600s, after her uncle John Hector sold his land so he could live with other natives and take advantage of opportunities in Worcester. Sarah Cisco decided that she would stay on her land and fight for it.

In the early 2000s, there was excavation work done at the Hassanamisco Reservation to find the remains of Sarah Boston's farmstead. Sarah Boston was the great granddaughter of Sarah Robins. This site was the original land through which Sarah Robins started the tradition of female inheritance. Through this excavation, it was learned that the farmstead relied on the breeding and cultivation of animals for meat. It was also learned how she and others prepared food, what was eaten and how they procured it, which are all "culturally informed choices."

Conversion to Christianity

In the seventeenth century, a Protestant missionary by the name of John Eliot spoke in Northeastern Connecticut in an attempt to convert the local Native Americans to Christianity. On Nipmuc land and territory, Eliot created seven "praying towns," but throughout Massachusetts and Connecticut, there were fourteen of them in total. The present day Hassanamisco Reservation located in Grafton, Massachusetts was briefly a praying town in 1728 when it was called the town of Hassanamesit. Eliot created these towns in order to convert as many Native American tribes as he was able. The Hassanamesit was already an established community when Eliot arrived, so he claimed it in order to convert the people already living there to Christianity. These towns had the backing of the Massachusetts government at the time. Eliot believed that the indigenous people not only needed to learn the Gospel, but to also adopt European ways of living. While living in these towns, the Native inhabitants were not allowed to practice any of their traditions. To enforce this way of living, the "Praying Indians" of the towns were given eight rules that they needed to follow and if they did not, were forced to pay a fine. These rules included restrictions of what one's hair might look like; men were told they could not have long hair and women were required to have their hair pulled back. This was done in an effort to culturally assimilate the indigenous people living there; as a part of Eliot's efforts to convert the Nipmuc people to Christianity and to make them more "civilized," he wanted the people in Hassanamesit to raise livestock. A superintendent at the time, Daniel Gookin, praised the Hassanmesit town for their ability to raise livestock. He stated that their way of keeping cattle and pigs was "better than any other Indians," but "very far short of the English both in diligence and providence." The praying towns in Northeastern Connecticut were shut down after the beginning of King Phillip's war because the residents fled to other, safer towns.

King Phillip's War

Metacom, also known as King Phillip, recruited many different Native American tribes in New England to fight with him in his conflict with the colonists. Thousands of Native Americans were killed in this war, including members of the Nipmuc tribe. During the war, the Nipmucs, along with several other tribes, attacked Brookfield and set fire to Springfield, Massachusetts. It was reported that after the attack, both towns were extremely surprised because they believed that they had a relationship built on trust and that they were friends. In August 1675, the members of Hassanamesit praying town, along with four other towns were banned from leaving the settlement under threat of being put in jail or being killed. This was because the colonists were concerned that if they left, they would join King Phillip's struggle against colonial expansion. October of the same year, non-combatant Nipmuc were relocated to Deer Island, in Boston harbor, for the winter, where more than half died from exposure and starvation. At the end of the war, the Nipmuc tribe members who had joined King Phillip, that did not manage to escape, were either killed or sold into slavery to the West Indies.

John Milton Earle and Intermarriage

In the late 1900s, the tribe petitioned the U.S Government to obtain federal acknowledgement and was ultimately denied. It is thought that the reason why was because of John Milton Earle. In 1859, Earle, who was a politician from Worcester, was named the Massachusetts Indian Commissioner. At that time, both Native Americans and African Americans were marginalized groups. Through their mistreatment by the Anglo-Americans, they were brought together. Both groups were spread through the villages in New England and African American men met Native American women while they both worked in their prospective jobs. These meetings often led to marriages between the two. Oftentimes the Native American women would buy their future husbands out of slavery so they could be both free and wed. That meant that any child they had would also not be a slave. However, the children of interracial couples were also seen as not truly Native American by many white people in New England. At that time, racial distinction was important for the Anglo-Americans, and it was becoming difficult to tell what race people were because of the number of interracial families. The number of intermarriages especially increased after times of war as a result of the number of deaths of Native American men. Although Native American men did marry African American women, it was far less common for them to do so.

In 1861, John Earle released a report stating that the Native Americans could no longer be considered a tribe because of the intermarriages with African Americans. He stated that the tribe was no longer culturally distinct and not autonomous. This report was used by the Office of Federal Acknowledgement in 2004 to deny the Nipmuc people federal recognition as a nation.

Current Status

Today, there are almost 600 Nipmuc tribe members living in the community, making it one of the largest Native American nations in New England. The land that the people currently own is the only land remaining of the original Hassanamesit settlement. The reservation land is both open and wooded. Although they are a "state acknowledged tribe" by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, they are not recognized as a nation at the federal level. In 1980, the Nipmuc people filed a petition with the Bureau of Indian Affairs to gain recognition, but were ultimately denied because the tribe did not meet several of the criteria. For example, they could not be identified as an "American Indian entity on a substantially continuous basis since 1900." Each year in July, the tribe holds the annual Nipmuc Powwow, where there is singing, dancing, and a naming ceremony. Both Native Americans and non-natives come to this event. In 2011 the reservation was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in an effort to preserve the land for Native Americans.

Cisco Homestead

The Cisco Homestead is the central building of the Hassanamisco Reservation and is currently being restored by members of the tribe. Approximately 150 years ago the building was named after the Cisco family, but it had been standing long before it had received its name, having been built in 1801. It is thought that the Cisco Homestead is the oldest timber-framed building that is still used by Native Americans to this day. To the Hassanamisco Nipmuc people, the homestead and the reservation land are reminders of all of the struggles that the people have overcome and are symbols of hope that they will survive in the future. Having a historic building on Nipmuc land has helped in ensuring that the reservation land will not be sold to those who are not in the Nipmuc tribe. Through money given by the Grafton Community Preservation Committee, restorations on the homestead were able to be made.