Harry T. Moore facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Harry T. Moore

|

|

|---|---|

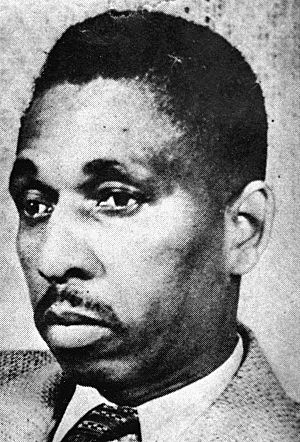

Undated photo of Harry T. Moore

|

|

| Born | November 18, 1905 Houston, Suwannee County, Florida, United States

|

| Died | December 25, 1951 (aged 46) Seminole County, Florida, United States

|

| Occupation | Educator, civil rights pioneer |

| Spouse(s) | Harriette Vyda Simms Moore |

Harry Tyson Moore (November 18, 1905 – December 25, 1951) was an African-American educator, a pioneer leader of the civil rights movement, founder of the first branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Brevard County, Florida, and president of the state chapter of the NAACP.

Harry T. Moore and his wife, Harriette Moore, also an educator, were the victims of a bombing of their home in Mims, Florida, on Christmas night 1951. As the local hospital in Titusville would not treat Blacks, he died on the way to the nearest one that would, a Black hospital in Sanford, Florida, about 30 miles to the northwest. His wife died from her wounds nine days later, on January 3, 1952, at the same hospital. This followed their both having been fired from teaching because of their activism.

The murder case was investigated, including by the FBI in 1951–1952, but no one was ever prosecuted. Two more investigations were conducted in the 1970s and 1990s. A state investigation and forensic work in 2005–2006 resulted in naming the likely perpetrators as four Ku Klux Klan members, all long dead by that time. Harry T. Moore was the first NAACP member and official to be assassinated for civil rights activism; the couple are the only husband and wife to be killed for the movement. Moore has been called the first martyr of this stage of the civil rights movement that expanded in the 1960s.

In the early 1930s, Moore had become state secretary for the Florida chapter of the NAACP. Through his registration activities, he greatly increased the number of members, and he worked on issues of housing and education. He investigated lynchings, filed lawsuits against voter registration barriers and white primaries, and worked for equal pay for black teachers in public schools.

Moore also led the Progressive Voters League. Following a 1944 US Supreme Court ruling against white primaries, between 1944 and 1950, he succeeded in increasing the registration of black voters in Florida to 31 percent of those eligible to vote, markedly higher than in any other Southern state.

Contents

Early life and family

Harry Tyson Moore was born on November 18, 1905, in Houston, Florida, a tiny farming community in Suwanee County. He was the only child of Johnny and Rosa Moore. His father tended the water tanks for the Seaboard Air Line Railroad and ran a small store in front of his house. Johnny started having health issues when Harry was nine years old and died that year in 1914. His widow, Rosa, tried to manage alone, working in the cotton fields and running the small store on weekends.

In 1915, Rosa sent Harry to live with one of her sisters in Daytona Beach. The following year, he moved to Jacksonville, where he lived for the next three years with three other aunts: Jesse, Adrianna, and Masie Tyson, who shared a household. That would prove to be the most important period in his formative years. Jacksonville had a large and vibrant African-American community, with a proud tradition of independence and intellectual achievement. Moore's aunts were educated, well-informed women (two were educators and one was a nurse), who took thr spindly, intelligent boy into their house on Louisiana Street and treated him like the son they had never had. Under their nurturing guidance, Moore's natural inquisitiveness and love of learning were reinforced.

After three years in Jacksonville, he returned home to Suwanee County in 1919 and enrolled in the high school program of Florida Memorial College. Over the next four years, Moore excelled in his studies, and he was nicknamed "Doc" by his classmates. In May 1925, at age 19, he graduated from Florida Memorial College with a "normal degree" (for teaching in the elementary grades) and accepted a teaching job in Cocoa, Florida, in the watery wilderness of Brevard County.

For the next two years, Moore taught fourth grade at Cocoa's only black elementary school. During his first year in Brevard County, he met Harriette Vyda Simms, an attractive older woman (she was 23, and he was barely 20). She had taught school herself, but was then selling insurance for the Atlanta Life Insurance Company, a major black-owned business. Within a year they were married, on Christmas Day 1926.

Both the Moores completed college degrees at Bethune Cookman College, a historically black college in Daytona Beach.

The Syms family lived in Mims, a small citrus town outside the county seat of Titusville. The newlyweds moved in with Harriette's parents until they built their own house on an adjoining acre of land. Meanwhile, Harry had been promoted to principal of the Titusville Colored School, which went from fourth through ninth grades. He taught ninth grade and supervised a staff of six teachers.

On March 28, 1928, their eldest daughter, Annie Rosalea, nicknamed "Peaches," was born. When Peaches was six months old, Harriette began teaching at the Mims Colored School. On September 30, 1930, their "baby daughter," Juanita Evangeline, was born. Both their daughters also earned college degrees at Bethune Cookman College. Peaches died in August 1972, at the age of 44. Juanita Evangeline died at the age of 85 in October 2015.

Civil rights activism

In 1934, soon after the birth of their daughters, the Moores founded the Brevard County chapter of the NAACP. Moore also helped organize the statewide NAACP organization. Through his registration activities, he greatly increased the number of members, and he worked on issues of housing and education. He investigated lynchings, filed lawsuits against voter registration barriers and white primaries, and worked for equal pay for black teachers in public schools, although they were segregated.

In 1946 both Moores were fired from their teaching jobs because of their activism; Harry Moore was working to gain equal pay for Black public school teachers in the Brevard County segregated school system. Such economic retaliation was widely used in Southern states to discourage activism. Harry Moore accepted a paid position with the NAACP in order to survive economically.

Moore also led the Progressive Voters League. Following a 1944 US Supreme Court ruling against white primaries as unconstitutional (which the Democratic Party had used as another means of excluding blacks from politics), between 1944 and 1950, Moore succeeded in increasing the registration of black voters in Florida to 31 percent of those eligible to vote, markedly higher than in any other Southern state.

Groveland case

In July 1949, four black men were accused of assault on a white woman in Groveland, Florida. Ernest Thomas fled the county and was killed by a posse; the other three suspects were arrested and beaten while held in custody, forcing two to confess. Rumors accompanied the case against a background of post-war tensions resulting from problems in absorbing veterans into jobs and American society. In Groveland, a white mob of more than 400 demanded that the sheriff, Willis V. McCall, who had hidden the prisoners to protect them, hand the prisoners over for lynching. The mob left the jail and went on a rampage, burning buildings in the black district of town. McCall asked the governor to send in the National Guard, but six days were needed to restore order.

The three young men, one 16 years of age and a minor, were found guilty by an all-white jury. The judge sentenced 16-year-old Charles Greenlee to life in prison; Sam Shepherd and Walter Irvin were sentenced to death.

Executive Director of the Florida NAACP, Harry T. Moore, organized a campaign against what he saw as the wrongful convictions of the three men. With NAACP support, appeals were pursued. In April 1951, a legal team headed by Thurgood Marshall won the appeal of Shepherd and Irvin's convictions before the U.S. Supreme Court. A new trial was scheduled.

County Sheriff McCall was responsible for transporting Shepherd and Irvin to the new trial venue in November 1951. He claimed that the two men, both handcuffed, attacked him in an escape attempt. He shot them both, and Shepherd died at the scene. Irvin survived his wounds; he later claimed to NAACP and FBI officials that the sheriff shot both him and Shepherd in cold blood. Moore called for an indictment against Sheriff McCall and called on Florida Governor Fuller Warren to suspend McCall from office.

Legacy and honors

- Langston Hughes wrote, and read publicly, the poem "The Ballad of Harry Moore", written posthumously in Moore's honor:

Florida means land of flowers

It was on a Christmas night.

In the state named for the flowers

Men came bearing dynamite ...

It could not be in Jesus' name

Beneath the bedroom floor

On Christmas night the killers

Hid the bomb for Harry Moore.

- Sweet Honey in the Rock set this Hughes poem to music, recording the song "The Ballad of Harry Moore".

- In 1952, Moore posthumously was awarded the Spingarn Medal by the NAACP for outstanding achievement by an African American.

Although the story of the Moores' lives receded into obscurity for years, interest in them has been revived in the late 20th century by books, documentaries, and a new investigation of their murders. New memorials have been named or designated in their honor. For example:

- In 1999, the state of Florida approved designation of the Moores' home site as a Florida Heritage Landmark, and Brevard County started restoring the site.

- By 2004, the Brevard County had created the Harry T. and Harriette Moore Memorial Park and Interpretive Center at the home site in Mims.

- Brevard County named its Justice Center after the Moores and included material there about their lives and work.

- Harry T. Moore Avenue in Mims, Florida is named after him.

- In March 2013, the Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore Post Office in Cocoa, Florida was named in their honor.

- In 2012, the Florida Legislature designated State Road 46 (SR-46) in Brevard County as the Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore Memorial Highway.

- In 2013, Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore were inducted into the Florida Civil Rights Hall of Fame.

21st century investigation

The state twice returned to the Moore murders but was unable to file charges, since most of the men whom it suspected in the crime had died.

In 1999, journalist Ben Green published a book based on his research of the case: Before His Time: The Untold Story of Harry T. Moore, America's First Civil Rights Martyr. His research had gone deeply into FBI files. Green's book was followed by a Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) show about Moore's life, Freedom Never Dies: The Legacy of Harry T. Moore (2000).

In 2005, Florida Attorney General Charlie Crist re-opened a state investigation of Harry and Harriette Moore's deaths. The Moores' only surviving daughter, Juanita Evangeline Moore, encouraged Crist in the efforts to uncover the identity of her parents' killers.

Forensics teams combed the former site of the Moores' house for evidence (the site is now within a memorial park). On August 16, 2006, Crist announced the results of the work of the state Office of Civil Rights and the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. Rumors linking Sheriff Willis V. McCall to the crime were proven false. Based on extensive evidence, the state concluded that the Moores were victims of a conspiracy by members of a Central Florida Klavern of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

The investigators published a report naming the following four individuals, all of whom had reputations for violence, as having been directly involved:

- Earl J. Brooklyn, a Klansman known for being exceedingly violent, who had floor plans of the Moores' home and was recruiting volunteers for an attack. He died about a year after the attack, apparently of natural causes.

- Tillman H. Belvin, another violent Klansman, was a close friend of Brooklyn's. He also died of natural causes about a year after the attack.

- Joseph Neville Cox, secretary of the Orange County, Florida chapter of the Klan, was believed to have ordered the attack. In 1952, he died after having been pressed with questioning and investigation by the FBI.

- Edward L. Spivey, also in the KKK. As he was dying of cancer in 1978, he implicated Cox in the attack, and claimed also to have been at the crime scene in 1951.