Greek genocide facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Greek genocide |

|

|---|---|

| Part of World War I, the aftermath of World War I and the late Ottoman genocides | |

| Location | Ottoman Empire |

| Date | 1913–1923 |

| Target | Greek population, particularly from Pontus, Cappadocia, Ionia and Eastern Thrace |

|

Attack type

|

Deportation, genocide, ethnic cleansing, death marches |

| Deaths | 300,000–900,000 (see casualties section below) |

| Perpetrators | Ottoman Empire, Turkish National Movement |

| Trials | Ottoman Special Military Tribunal |

| Motive | Anti-Greek sentiment, Turkification, Anti-Eastern Orthodox sentiment |

The Greek genocide (Greek: Γενοκτονία των Ελλήνων, romanized: Genoktonía ton Ellínon), which included the Pontic genocide, was the systematic killing of the Christian Ottoman Greek population of Anatolia, which was carried out mainly during World War I and its aftermath (1914–1922) – including the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923) – on the basis of their religion and ethnicity. It was perpetrated by the government of the Ottoman Empire led by the Three Pashas and by the Government of the Grand National Assembly led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, against the indigenous Greek population of the Empire. The genocide included massacres, forced deportations involving death marches through the Syrian Desert, expulsions, summary executions, and the destruction of Eastern Orthodox cultural, historical, and religious monuments. Several hundred thousand Ottoman Greeks died during this period. Most of the refugees and survivors fled to Greece (adding over a quarter to the prior population of Greece). Some, especially those in Eastern provinces, took refuge in the neighbouring Russian Empire.

By late 1922, most of the Greeks of Asia Minor had either fled or had been killed. Those remaining were transferred to Greece under the terms of the later 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey, which formalized the exodus and barred the return of the refugees. Other ethnic groups were similarly attacked by the Ottoman Empire during this period, including Assyrians and Armenians, and some scholars and organizations have recognized these events as part of the same genocidal policy.

The Allies of World War I condemned the Ottoman government–sponsored massacres. In 2007, the International Association of Genocide Scholars passed a resolution recognising the Ottoman campaign against its Christian minorities, including the Greeks, as genocide. Some other organisations have also passed resolutions recognising the Ottoman campaign against these Christian minorities as genocide, as have the national legislatures of Greece, Cyprus, the United States, Sweden, Armenia, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic.

Contents

Background

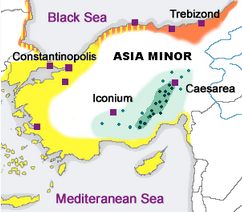

At the outbreak of World War I, Asia Minor was ethnically diverse, its population included Turks and Azeris, as well as groups that had inhabited the region prior to the Ottoman conquest, including Pontic Greeks, Caucasus Greeks, Cappadocian Greeks, Armenians, Kurds, Zazas, Georgians, Circassians, Assyrians, Jews, and Laz people.

Among the causes of the Turkish campaign against the Greek-speaking Christian population was a fear that they would welcome liberation by the Ottoman Empire's enemies, and a belief among some Turks that to form a modern country in the era of nationalism it was necessary to purge from their territories all minorities who could threaten the integrity of an ethnically based Turkish nation.

According to a German military attaché, the Ottoman minister of war Ismail Enver had declared in October 1915 that he wanted to "solve the Greek problem during the war … in the same way he believe[d] he solved the Armenian problem", referring to the Armenian genocide. Germany and the Ottoman Empire were allies immediately before, and during World War I. By 31 January 1917, the Chancellor of Germany Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, reported that:

The indications are that the Turks plan to eliminate the Greek element as enemies of the state, as they did earlier with the Armenians. The strategy implemented by the Turks is of displacing people to the interior without taking measures for their survival by exposing them to death, hunger, and illness. The abandoned homes are then looted and burnt or destroyed. Whatever was done to the Armenians is being repeated with the Greeks.

Origin of the Greek minority

The Greek presence in Asia Minor dates at least from the Late Bronze Age (1450 BC). The Greek poet Homer lived in the region around 800 BC. The geographer Strabo referred to Smyrna as the first Greek city in Asia Minor, and numerous ancient Greek figures were natives of Anatolia, including the mathematician Thales of Miletus (7th century BC), the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus (6th century BC), and the founder of Cynicism Diogenes of Sinope (4th century BC). Greeks referred to the Black Sea as the "Euxinos Pontos" or "hospitable sea" and starting in the eighth century BC they began navigating its shores and settling along its Anatolian coast. The most notable Greek cities of the Black Sea were Trebizond, Sampsounta, Sinope and Heraclea Pontica.

During the Hellenistic period (334 BC – 1st century BC), which followed the conquests of Alexander the Great, Greek culture and language began to dominate even the interior of Asia Minor. The Hellenization of the region accelerated under Roman and early Byzantine rule, and by the early centuries AD the local Indo-European Anatolian languages had become extinct, being replaced by the Koine Greek language. From this point until the late Middle Ages all of the indigenous inhabitants of Asia Minor practiced Christianity (called Greek Orthodox Christianity after the East–West Schism with the Catholics in 1054) and spoke Greek as their first language.

The resultant Greek culture in Asia Minor flourished during a millennium of rule (4th century – 15th century AD) under the mainly Greek-speaking Eastern Roman Empire. Those from Asia Minor constituted the bulk of the empire's Greek-speaking Orthodox Christians; thus, many renowned Greek figures during late antiquity, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance came from Asia Minor, including Saint Nicholas (270–343 AD), rhetorician John Chrysostomos (349–407 AD), Hagia Sophia architect Isidore of Miletus (6th century AD), several imperial dynasties, including the Phokas (10th century) and Komnenos (11th century), and Renaissance scholars George of Trebizond (1395–1472) and Basilios Bessarion (1403–1472).

Thus, when the Turkic peoples began their late medieval conquest of Asia Minor, Byzantine Greek citizens were the largest group of inhabitants there. Even after the Turkic conquests of the interior, the mountainous Black Sea coast of Asia Minor remained the heart of a populous Greek Christian state, the Empire of Trebizond, until its eventual conquest by the Ottoman Turks in 1461, a year after the Ottomans conquered the area of Europe which is now the Greek mainland. Over the next four centuries the Greek natives of Asia Minor gradually became a minority in these lands under the now dominant Turkic culture.

Events

Balkan Wars to World War I

| Greek census (1910–1912) | Ottoman census (1914) | Soteriades (1918) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hüdavendigâr (Prousa) | 262,319 | 184,424 | 278,421 |

| Konya (Ikonio) | 74,539 | 65,054 | 66,895 |

| Trabzon (Trebizond) | 298,183 | 260,313 | 353,533 |

| Ankara (Angora) | 85,242 | 77,530 | 66,194 |

| Aydin | 495,936 | 319,079 | 622,810 |

| Kastamonu | 24,349 | 26,104 | 24,937 |

| Sivas | 74,632 | 75,324 | 99,376 |

| İzmit (Nicomedia) | 52,742 | 40,048 | 73,134 |

| Biga (Dardanelles) | 31,165 | 8,541 | 32,830 |

| Total | 1,399,107 | 1,056,357 | 1,618,130 |

Beginning in the spring of 1913, the Ottomans implemented a programme of expulsions and forcible migrations, focusing on Greeks of the Aegean region and eastern Thrace, whose presence in these areas was deemed a threat to national security. The Ottoman government adopted a "dual-track mechanism", whereby official government acts were accompanied by unofficial covert, extralegal, but state-sponsored acts of terror under the protective umbrella of state policies, thereby allowing the Ottoman government to deny responsibility for and prior knowledge of this campaign of intimidation, emptying Christian villages. The involvement in certain cases of local military and civil functionaries in planning and executing anti-Greek violence and looting led ambassadors of Greece and the Great Powers and the Patriarchate to address complaints to the Sublime Porte. In protest to government inaction in the face of these attacks and to the so-called "Muslim boycott" of Greek products that had begun in 1913, the Patriarchate closed Greek churches and schools in June 1914. Responding to international and domestic pressure, Talat Pasha headed a visit in Thrace in April 1914 and later in the Aegean to investigate reports and try to soothe bilateral tension with Greece. While claiming that he had no involvement or knowledge of these events, Talat met with Kuşçubaşı Eşref, head of the "cleansing" operation in the Aegean littoral, during his tour and advised him to be cautious not to be "visible". Also, after 1913 there were organized boycotts against the Greeks, initiated by the Ottoman Interior Ministry who asked the empire's provinces to start them. The British ambassador in Constantinople at that time described the boycott as a direct result of the Committee of Union and Progress and that "Committee emissaries are everywhere instigating the people", adding that every person, Greek or Muslim, who entered a non-Muslim shop was beaten.

One of the worst attacks of this campaign took place in Phocaea (Greek: Φώκαια), on the night of 12 June 1914, a town in western Anatolia next to Smyrna, where Turkish irregular troops destroyed the city, killing 50 or 100 civilians and causing its population to flee to Greece. French eyewitness Charles Manciet states that the atrocities he had witnessed at Phocaea were of an organized nature that aimed at circling Christian peasant populations of the region. In another attack against Serenkieuy, in Menemen district, the villagers formed armed resistance groups but only a few managed to survive being outnumbered by the attacking Muslim irregular bands. During the summer of the same year the Special Organization (Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa), assisted by government and army officials, conscripted Greek men of military age from Thrace and western Anatolia into Labour Battalions in which hundreds of thousands died. These conscripts, after being sent hundreds of miles into the interior of Anatolia, were employed in road-making, building, tunnel excavating and other field work; but their numbers were heavily reduced through privations and ill-treatment and through outright massacre by their Ottoman guards.

Following similar accords made with Bulgaria and Serbia, the Ottoman Empire signed a small voluntary population exchange agreement with Greece on 14 November 1913. Another such agreement was signed 1 July 1914 for the exchange of some "Turks" (that is, Muslims) of Greece for some Greeks of Aydin and Western Thrace, after the Ottomans had forced these Greeks from their homes in response to the Greek annexation of several islands. The swap was never completed due to the eruption of World War I. While discussions for population exchanges were still conducted, Special Organization units attacked Greek villages forcing their inhabitants to abandon their homes for Greece, being replaced with Muslim refugees.

The forceful expulsion of Christians of western Anatolia, especially Ottoman Greeks, has many similarities with policy towards the Armenians, as observed by US ambassador Henry Morgenthau and historian Arnold Toynbee. In both cases, certain Ottoman officials, such as Şükrü Kaya, Nazım Bey and Mehmed Reshid, played a role; Special Organization units and labour battalions were involved; and a dual plan was implemented combining unofficial violence and the cover of state population policy. This policy of persecution and ethnic cleansing was expanded to other parts of the Ottoman Empire, including Greek communities in Pontus, Cappadocia, and Cilicia.

World War I

According to a newspaper of the time, in November 1914, Turkish troops destroyed Christian properties and murdered several Christians at Trabzon. After November 1914 Ottoman policy towards the Greek population shifted; state policy was restricted to the forceful migration to the Anatolian hinterland of Greeks living in coastal areas, particularly the Black Sea region, close to the Turkish-Russian front. This change of policy was due to a German demand for the persecution of Ottoman Greeks to stop, after Eleftherios Venizelos had made this a condition of Greece's neutrality when speaking to the German ambassador in Athens. Venizelos also threatened to undertake a similar campaign against Muslims that were living in Greece if Ottoman policy did not change. While the Ottoman government tried to implement this change in policy, it was unsuccessful and attacks, even murders, continued to occur unpunished by local officials in the provinces, despite repeated instructions in cables sent from the central administration. Arbitrary violence and extortion of money intensified later, providing ammunition for the Venizelists arguing that Greece should join the Entente.

In July 1915 the Greek chargé d'affaires claimed that the deportations "can not be any other issue than an annihilation war against the Greek nation in Turkey and as measures hereof they have been implementing forced conversions to Islam, in obvious aim to, that if after the end of the war there again would be a question of European intervention for the protection of the Christians, there will be as few of them left as possible." According to George W. Rendel of the British Foreign Office, by 1918 "over 500,000 Greeks were deported of whom comparatively few survived". In his memoirs, the United States ambassador to the Ottoman Empire between 1913 and 1916 wrote "Everywhere the Greeks were gathered in groups and, under the so-called protection of Turkish gendarmes, they were transported, the larger part on foot, into the interior. Just how many were scattered in this fashion is not definitely known, the estimates varying anywhere from 200,000 up to 1,000,000."

Despite the shift of policy, the practice of evacuating Greek settlements and relocating the inhabitants was continued, albeit on a limited scale. Relocation was targeted at specific regions that were considered militarily vulnerable, not the whole of the Greek population. As a 1919 Patriarchate account records, the evacuation of many villages was accompanied with looting and murders, while many died as a result of not having been given the time to make the necessary provisions or of being relocated to uninhabitable places.

State policy towards Ottoman Greeks changed again in the fall of 1916. With Entente forces occupying Lesbos, Chios and Samos since spring, the Russians advancing in Anatolia and Greece expected to enter the war siding with the Allies, preparations were made for the deportation of Greeks living in border areas. In January 1917 Talat Pasha sent a cable for the deportation of Greeks from the Samsun district "thirty to fifty kilometres inland" taking care for "no assaults on any persons or property". However, the execution of government decrees, which took a systematic form from December 1916, when Behaeddin Shakir came to the region, was not conducted as ordered: men were taken in labour battalions, women and children were attacked, villages were looted by Muslim neighbours. As such in March 1917 the population of Ayvalık, a town of c. 30,000 inhabitants on the Aegean coast was forcibly deported to the interior of Anatolia under order by German General Liman von Sanders. The operation included death marches, looting, and massacre against the civilian population. Germanos Karavangelis, the bishop of Samsun, reported to the Patriarchate that thirty thousands had been deported to the Ankara region and the convoys of the deportees had been attacked, with many being killed. Talat Pasha ordered an investigation for the looting and destruction of Greek villages by bandits. Later in 1917 instructions were sent to authorize military officials with the control of the operation and to broaden its scope, now including persons from cities in the coastal region. However, in certain areas Greek populations remained undeported.

Greek deportees were sent to live in Greek villages in the inner provinces or, in some case, villages where Armenians were living before being deported. Greek villages evacuated during the war due to military concerns were then resettled with Muslim immigrants and refugees. According to cables sent to the provinces during this time, abandoned movable and non-movable Greek property was not to be liquidated, as that of the Armenians, but "preserved".

On 14 January 1917 Cossva Anckarsvärd, Sweden's Ambassador to Constantinople, sent a dispatch regarding the decision to deport the Ottoman Greeks:

What above all appears as an unnecessary cruelty is that the deportation is not limited to the men alone, but is extended likewise to women and children. This is supposedly done in order to much easier be able to confiscate the property of the deported.

According to Rendel, atrocities such as deportations involving death marches, starvation in labour camps etc. were referred to as "white massacres". Ottoman official Rafet Bey was active in the genocide of the Greeks and in November 1916, Austrian consul in Samsun, Kwiatkowski, reported that he said to him "We must finish off the Greeks as we did with the Armenians ... today I sent squads to the interior to kill every Greek on sight".

Pontic Greeks responded by forming insurgent groups, which carried weapons salvaged from the battlefields of the Caucasus Campaign of World War I or directly supplied by the Russian army. In 1920, the insurgents reached their peak in regard to manpower numbering 18,000 men. On 15 November 1917, Ozakom delegates agreed to create a unified army composed of ethnically homogeneous units, Greeks were allotted a division consisting of three regiments. The Greek Caucasus Division was thus formed out of ethnic Greeks serving in Russian units stationed in the Caucasus and raw recruits from among the local population including former insurgents. The division took part in numerous engagements against the Ottoman army as well as Muslim and Armenian irregulars, safeguarding the withdrawal of Greek refugees into the Russian held Caucasus, before being disbanded in the aftermath of the Treaty of Poti.

Greco-Turkish War

After the Ottoman Empire capitulated on 30 October 1918, it came under the de jure control of the victorious Entente Powers. However, the latter failed to bring the perpetrators of the genocide to justice, although in the Turkish Courts-Martial of 1919–20 a number of leading Ottoman officials were accused of ordering massacres against both Greeks and Armenians. Thus, killings, massacres and deportations continued under the pretext of the national movement of Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk).

The systematic massacre and deportation of Greeks in Asia Minor, a program which had come into effect in 1914, was a precursor to the atrocities perpetrated by both the Greek and Turkish armies during the Greco-Turkish War, a conflict which followed the Greek landing at Smyrna in May 1919 and continued until the retaking of Smyrna by the Turks and the Great Fire of Smyrna in September 1922. Rudolph Rummel estimated the death toll of the fire at 100,000 Greeks and Armenians, who perished in the fire and accompanying massacres. According to Norman M. Naimark "more realistic estimates range between 10,000 to 15,000" for the casualties of the Great Fire of Smyrna. Some 150,000 to 200,000 Greeks were expelled after the fire, while about 30,000 able-bodied Greek and Armenian men were deported to the interior of Asia Minor, most of whom were executed on the way or died under brutal conditions. George W. Rendel of the British Foreign Office noted the massacres and deportations of Greeks during the Greco-Turkish War. According to estimates by Rudolph Rummel, between 213,000 and 368,000 Anatolian Greeks were killed between 1919 and 1922. There were also massacres of Turks carried out by the Hellenic troops during the occupation of western Anatolia from May 1919 to September 1922.

For the massacres that occurred during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, British historian Arnold J. Toynbee wrote that it was the Greek landings that created the Turkish National Movement led by Mustafa Kemal: "The Greeks of 'Pontus' and the Turks of the Greek occupied territories, were in some degree victims of Mr. Venizelos's and Mr. Lloyd George's original miscalculations at Paris."

Relief efforts

In 1917 a relief organization by the name of the Relief Committee for Greeks of Asia Minor was formed in response to the deportations and massacres of Greeks in the Ottoman Empire. The committee worked in cooperation with the Near East Relief in distributing aid to Ottoman Greeks in Thrace and Asia Minor. The organisation disbanded in the summer of 1921 but Greek relief work was continued by other aid organisations.

Casualties

According to Benny Morris and Dror Ze'evi in The Thirty-Year Genocide, as a result of Ottoman and Turkish state policy, "several hundred thousand Ottoman Greeks had died."

For the whole of the period between 1914 and 1922 and for the whole of Anatolia, there are academic estimates of death toll ranging from 289,000 to 750,000.

Some contemporary sources claimed different death tolls. The Greek government collected figures together with the Patriarchate to claim that a total of one million people were massacred.

Aftermath

Article 142 of the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, prepared after the first World War, called the wartime Turkish regime "terrorist" and contained provisions "to repair so far as possible the wrongs inflicted on individuals in the course of the massacres perpetrated in Turkey during the war." The Treaty of Sèvres was never ratified by the Turkish government and ultimately was replaced by the Treaty of Lausanne. That treaty was accompanied by a "Declaration of Amnesty", without containing any provision in respect to punishment of war crimes.

In 1923, a population exchange between Greece and Turkey resulted in a near-complete ending of the Greek ethnic presence in Turkey and a similar ending of the Turkish ethnic presence in much of Greece. According to the Greek census of 1928, 1,104,216 Ottoman Greeks had reached Greece. It is impossible to know exactly how many Greek inhabitants of Turkey died between 1914 and 1923, and how many ethnic Greeks of Anatolia were expelled to Greece or fled to the Soviet Union. Some of the survivors and expelled took refuge in the neighboring Russian Empire (later, Soviet Union). Similar plans for a population exchange had been negotiated earlier, in 1913–1914, between Ottoman and Greek officials during the first stage of the Greek genocide but had been interrupted by the onset of World War I.

In 1955, the Istanbul Pogrom caused most of the remaining Greek inhabitants of Istanbul to flee the country. Historian Alfred-Maurice de Zayas identifies the pogrom as a crime against humanity and he states that the flight and migration of Greeks afterwards corresponds to the "intent to destroy in whole or in part" criteria of the Genocide Convention.

Memorials

Memorials commemorating the plight of Ottoman Greeks have been erected throughout Greece, as well as in a number of other countries including Australia, Canada, Germany, Sweden, and the United States.

See also

- Armenian genocide

- Sayfo

- Burning of Smyrna

- Deportations of Kurds (1916–1934)

- Greek refugees

- Republic of Pontus