Government in early modern Scotland facts for kids

Government in early modern Scotland included all forms of administration, from the crown, through national institutions, to systems of local government and the law, between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth century. It roughly corresponds to the early modern era in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the last Jacobite risings and the beginnings of the industrial revolution. Monarchs of this period were the Stuarts: James IV, James V, Mary Queen of Scots, James VI, Charles I, Charles II, James VII, William II and Mary II, Anne, and the Hanoverians: George I and George II.

The crown remained the most important element of government throughout the period and, despite the many royal minorities, it saw many of the aspects of aggrandisement associated with "new monarchy" elsewhere in Europe. Theories of limited monarchy and resistance were articulated by Scots, particularly George Buchanan, in the sixteenth century, but James VI advanced the theory of the divine right of kings, and these debates were restated in subsequent reigns and crises. The court remained at the centre of political life, and in the sixteenth century emerged as a major centre of display and artistic patronage. The Privy Council and the great offices of state, remained central to the administration of the government, even after the departure of the Stuart monarchs to rule in England from 1603, but they were often sidelined and was abolished after the Act of Union of 1707, with rule direct from London. Parliament was also vital to the running of the country, providing laws and taxation, but it had fluctuating fortunes and never achieved the centrality the national life of its counterpart in England before it was disbanded in 1707.

Revenue remained a continual problem for Scottish government, even after the introduction of regular taxation from the 1580s, with receipts insufficient for the business of government and, after 1603, much of the costs being paid out of English revenues. In local government, attempts were made increase its effectiveness, with the creation of Justices of Peace and Commissioners of Supply. The continued existence of courts baron and introduction of kirk sessions helped consolidate the power of local lairds. In law there was an expansion of central institutions and professionalisation of lawyers as a group. Scottish law was maintained as a separate system after the union in 1707 and from 1747 the central courts gained a clear authority over local institutions.

Contents

Crown

James V was the first Scottish monarch to wear the closed imperial crown, in place of the open circlet of medieval kings, suggesting a claim to absolute authority within the kingdom. His diadem was reworked to include arches in 1532, which were re-added when it was reconstructed in 1540 in what remains the Crown of Scotland. The idea of imperial monarchy emphasised the dignity of the crown and included its role as a unifying national force, defending national borders and interests, royal supremacy over the law and a distinctive national church within the Catholic communion. New monarchy can also be seen in the reliance of the crown on "new men" rather than the great magnates, the use of the clergy as a form of civil service, developing standing armed forces and a navy.

Major intellectual figures in the Reformation included George Buchanan (1506–82), whose works De Jure Regni apud Scotos (1579) and Rerum Scoticarum Historia (1582) were among the major texts outlining the case for resistance to tyrants. Buchanan was one of the young James VI's tutors and although they succeeded in producing a highly educated Protestant prince, who would publish works on subjects including government, poetry and witchcraft, they failed to intellectually convince him of their ideas about limited monarchy and he would debate with Buchanan and others over the status of the crown and kirk. James asserted the concept of "Divine right", by which a king was appointed by God and thus gained a degree of sanctity. These ideas he passed on to Charles I, whose ability to compromise may have been undermined by them, helping to lead to his political difficulties. When he was executed in 1649, the Scottish Covenanters objected, but avoided advancing the sanctity of kings as a reason. In 1689, when the Scottish Estates had to find a justification for deposing James VII they turned to Buchanan's argument on the contractual nature of monarchy in the Claim of Right.

Officers of state

The Chancellor was effectively the first minister of the kingdom. His department, the chancery, was responsible for the Great Seal, which was needed to process the inheritance of land titles and the confirmation of land transfers. His key responsibility was to preside at meetings of the privy council, and on those rare occasions he attended, at meetings of the court of session. The second most prestigious office was the Secretary, who was responsible for the records of the Privy council and for foreign policy, including the borders, despite which the post retained its importance after the Union of Crowns in 1603. The Treasurer was the last of the major posts and, with the Comptroller, dealt with the royal finances until the Comptroller's office was merged into the Treasurer's from 1610.

The Lord President of the Court of Session, often known simply as the Lord President, acted as a link between the Privy Council and the Court. The king's advocate acted as the legal council. The post emerged in the 1490s to deal with the king's patrimonial land rights and from 1555 there were usually two king's councillors, indicating the increase in the level of work. From 1579 they increasingly became a public prosecutor. After the union most of the offices remained, but political power was increasingly centred in London. John Ker, 1st Duke of Roxburghe, became the first Secretary of State for Scotland until the post was abolished in 1746 after the Jacobite Rising of 1745.

Parliament

In the sixteenth century, parliament usually met in Stirling Castle or the Old Tolbooth, Edinburgh, which was rebuilt on the orders of Mary Queen of Scots from 1561. King Charles I ordered the construction of Parliament Hall, at the expense of the Edinburgh burgesses, which was built between 1633 and 1639 and remained the parliament's home until it was dissolved in 1707. By the end of the Middle Ages the Parliament had evolved from the King's Council of Bishops and Earls into a 'colloquium' with a political and judicial role. The attendance of knights and freeholders had become important, and burgh commissioners joined them to form the Three Estates. It acquired significant powers over particular issues, including consent for taxation, but it also had a strong influence over justice, foreign policy, war, and other legislation, whether political, ecclesiastical, social or economic. Much of the legislative business of the Scottish parliament was carried out by a parliamentary committee known as the Lords of the Articles, chosen by the three estates to draft legislation which was then presented to the full assembly to be confirmed. Like many continental assemblies the Scottish Parliament was being called less frequently by the early sixteenth century and might have been dispensed with by the crown had it not been for the series of minorities and regencies that dominated from 1513. The crown was also able to call a Convention of Estates, which was quicker to assemble and could issue laws like parliament, making them invaluable in a crisis, but they could only deal with a specific issue and were more resistant to the giving of taxation rights to the crown.

Parliament played a major part in the Reformation crisis of the mid-sixteenth century. It had been used by James V to uphold Catholic orthodoxy and asserted its right to determine the nature of religion in the country, disregarding royal authority in 1560. The 1560 parliament included 100 lairds, who were predominantly Protestant, and who claimed a right to sit in the Parliament under the provision of a failed shire election act of 1428. Their position in the parliament remained uncertain and their presence fluctuated until the 1428 act was revived in 1587 and provision made for the annual election of two commissioners from each shire (except Kinross and Clackmannan, which had one each). The property qualification for voters was for freeholders who held land from the crown of the value of 40s of auld extent. This excluded the growing class of feuars, who would not gain these rights until 1661. The clerical estate was marginalised in Parliament by the Reformation, with the laymen who had acquired the monasteries sitting as 'abbots' and 'priors'. Catholic clergy were excluded after 1567, but a small number of Protestant bishops continued as the clerical estate. James VI attempted to revive the role of the bishops from about 1600. They were abolished by the Covenanters in 1638, when Parliament became an entirely lay assembly. A further group appeared in the Parliament from the minority of James IV in the 1560s, with members of the Privy Council representing the king's interests, until they were excluded in 1641. James VI continued to manage parliament though the Lords of the Articles, who deliberated legislation before it reached the full parliament. He controlled the committee by filling it with royal officers as non-elected members, but was forced to limit this to eight from 1617.

Having been officially suspended at the end of the Cromwellian regime, parliament returned after the Restoration of Charles II in 1661. This parliament, known disparagingly as the 'Drunken Parliament', revoked most of the Presbyterian gains of the last thirty years. Subsequently Charles' absence from Scotland and use of commissioners to rule his northern kingdom undermined the authority of the body. James VII's parliament supported him against rivals and attempted rebellions, but after his escape to exile in 1689 William's first parliament was dominated by his supporters and, in contrast to the situation in England, effectively deposed James under the Claim of Right, which offered the crown to William and Mary, placing important limitations on royal power, including the abolition of the Lords of the Articles. Rosalind Mitchison argues that the parliament became a focus of national political life, but it never reached the position of a true centre of national identity attained by its English counterpart. The new Williamite parliament would subsequently bring about its own demise by the Act of Union in 1707. The English and Scottish parliaments were replaced by a combined Parliament of Great Britain, but it sat in Westminster and largely continued English traditions without interruption. Forty-five Scots were added to the 513 members of the House of Commons and 16 Scots to the 190 members of the House of Lords.

Images for kids

-

The Stirling Heads, carved roundels on the roof of the King's Chamber in Stirling Castle, include many members of the court of James V

-

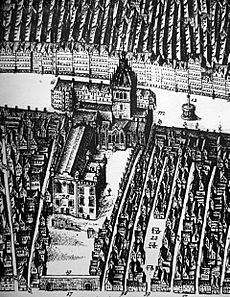

Detail from the so-called 'Hertford sketch' of Edinburgh in 1544, showing Holyrood Palace, described as 'the kyng of Skotts palas'

-

Institution of the Court of Session by James V in 1532, from the Great Window in Parliament Hall, Edinburgh