Georges Méliès facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès

|

|

|---|---|

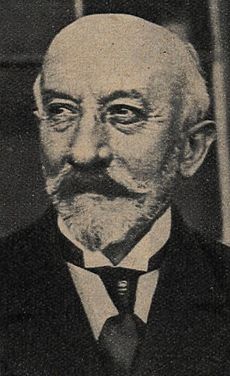

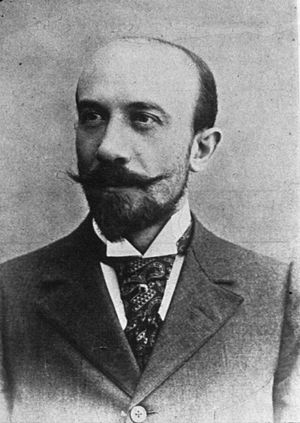

Georges Méliès, c. 1890

|

|

| Born |

Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès

8 December 1861 |

| Died | 21 January 1938 (aged 76) Paris, France

|

| Occupation | Film director, actor, set designer, illusionist, toymaker, costume designer |

| Years active | 1888–1923 |

| Spouse(s) |

Eugénie Génin

(m. 1885; died 1913)Jehanne D'Alcy

(m. 1925) |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

|

|

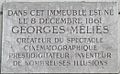

Georges Méliès (8 December 1861 – 21 January 1938) was a French moviemaker. He led the way in the use of special effects, multiple exposures, time-lapse photography, dissolves, and hand-painted colour in his work. His movies include Conquest of the Pole, A Trip to the Moon, and The Impossible Voyage. These movies involve strange, surreal voyages, like those in Jules Verne's books. These movies are among the most important early science fiction movies. Méliès's The Haunted Castle is an early horror movie.

Contents

Life and work

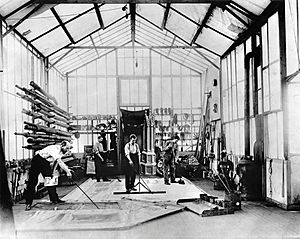

Méliès was born in Paris, France in 1861. He liked drawing and playing with a puppet theater as a child. He went to the theater often as a young man. About 1888, Méliès bought the Théatre Robert-Houdin and worked there as a magician. He became obsessed with moviemaking after seeing a movie by Antoine Lumière in 1895. In May 1896, he acquired his own movie camera and set up a movie studio. At the end of 1896, he formed a new company, Star Film.

Méliès began making movies that were three to nine minute long. He wrote, designed, filmed, and acted in nearly all of his movies. He liked putting magic tricks into his movies. While filming a street scene one day, the camera stopped briefly. When Méliès looked at the movie later, he noticed that at the moment of the break, the bus he had been filming suddenly disappeared and new vehicles replaced it. Making items appear and disappear by stopping and starting the camera would become one of his most commonly used movie tricks.

In 1902, Méliès produced his first masterpiece, A Trip to the Moon. It was inspired by several works of the time that speculated about life on the moon. H.G. Wells and Jules Verne wrote about space travel, for instance, and Offenbach composed an opera about a trip to the moon. Trip was a huge success in France. Méliès hoped to make a fortune showing it in the United States. Thomas Edison and other moviemakers made copies of Trip, however, and made money on Méliès's work. There was nothing he could do about these thieves.

Méliès' great success in 1902 continued with his three other major productions of that year. In The Coronation of Edward VII, Méliès reenacts the crowning of the new British King Edward VII. The film was shot prior to the actual event (since he was denied access to the coronation) and was commissioned by Charles Urban, head of the Warwick Trading Company and the Star Films representative in London. The film was ready to be released on the day of the coronation; however, the event was postponed for six weeks due to Edward's health. This allowed Méliès to add actual footage of the carriage procession in the film. The film was financially successful and King Edward VII was said to have enjoyed it. Next, Méliès made the féeries Gulliver's Travels Among the Lilliputians and the Giants, based on the novel by Jonathan Swift, and Robinson Crusoe, based on the novel by Daniel Defoe.

In 1903 Méliès made The Kingdom of the Fairies, which film critic Jean Mitry has called "undoubtedly Méliès's best film, and in any case the most intensely poetic". The Los Angeles Times called the film "an interesting exhibit of the limits to which moving picture making can be carried in the hands of experts equipped with time and money to carry out their devices". Prints of the film survive in the film archives of the British Film Institute and the U.S. Library of Congress.

Méliès continued the year by perfecting many of his camera effects, such as more fast-paced transformations in Ten Ladies in One Umbrella and the seven superimpositions that he used in The Melomaniac. He finished the year with a film based on the Faust legend, The Damnation of Faust. The film is loosely based on an opera by Hector Berlioz, but it pays less attention to the story and more to the special effects that represent a tour of hell. These include underground gardens, walls of fire and walls of water. In 1904, he made a sequel, Faust and Marguerite. This time, the film was based on an opera by Charles Gounod. Méliès also created a combined version of the two films that would sync up with the main arias of the operas. He continued making "high art" films later in 1904 such as The Barber of Seville. These films were popular with both audiences and critics at the time of their release, and helped Méliès establish more prestige.

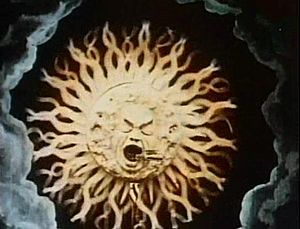

His major production of 1904 was The Impossible Voyage, a film similar to A Trip to the Moon about an expedition around the world, into the oceans and even to the sun. In the film, Méliès plays Engineer Mabouloff of the Institute of Incoherent Geography, who is similar to the previous Professor Barbenfouillis. Mabouloff leads a group on the trip on the many Automobouloffs, the vehicles that they use of their travels. As the men are traveling up to the highest peaks of the Alps, their vehicle continues moving upwards and takes them unexpectedly to the sun, which has a face much like the man in the moon and swallows the vehicle. Eventually the men use a submarine to launch back to earth and into the ocean, and are greeted back home by adoring admirers. The film was 24 minutes long and was a success. Film critic Lewis Jacobs has said that "the film expressed all of Méliès talents ... The complexity of his tricks, his resourcefulness with mechanical contrivances, the imaginativeness of the settings and the sumptuous tableaux made the film a masterpiece for its day."

In 1905, Victor de Cottens asked Méliès to collaborate with him on The Merry Deeds of Satan, a theatrical revue for the Théâtre du Châtelet. Méliès contributed two short films for the performances, Le Voyage dans l'espace (The Space Trip) and Le Cyclone (The Cyclone), and co-wrote the scenario with de Cottons for the entire revue. 1905 was also the 100th birthday of Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin, and the Théâtre Robert-Houdin created a special celebration performance, including Méliès' first new stage trick in several years, Les Phénomènes du Spiritisme. At the same time, he was again remodeling and expanding his studio at Montreuil by installing electric lights, adding a second stage and buying costumes from other sources. Méliès's films for 1905 include the adventure The Palace of the Arabian Nights and the féerie Rip's Dream, based on the Rip Van Winkle legend and the opera by Robert Planquette. In 1906, his output included an updated, comedic adaptation of the Faust legend The Merry Frolics of Satan and The Witch. But the féerie style that Méliès was best known for was beginning to lose popularity and he began to make films in other genres, such as crime and family films. In the U.S., Gaston Méliès had to reduce the sale prices of three of Méliès' earlier popular féeries, Cinderella, Bluebeard and Robinson Crusoe. By the end of 1905 Gaston had cut the prices of all films on the Star Films catalog by 20%, which did improve sales.

Later film career and decline

In 1907, Méliès created three new illusions for the stage and performed them at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin, while he continued producing a steady stream of films, including Under the Seas, and a short version of Shakespeare's Hamlet. Yet such film critics as Jean Mitry, Georges Sadoul, and others have declared that Méliès' work began to decline and, in the film scholar Miriam Rosen's words, to "lapse into the repetition of old formulas on the one hand and an uneasy imitation of new trends on the other."

In 1908, Thomas Edison created the Motion Picture Patents Company as a way to control the film industry in the United States and Europe. The companies that joined the conglomerate were Edison, Biograph, Vitagraph, Essanay, Selig, Lubin, Kalem, American Pathé and Méliès' Star Film Company, with Edison acting as president of the collective. Star Films was obligated to supply the MPPC with one thousand feet of film per week, and Méliès made 58 films that year in fulfillment of the obligation. Gaston Méliès established his own studio in Chicago, the Méliès Manufacturing Company, which helped his brother fulfill the obligation to Edison, although Gaston produced no films in 1908. That year, Méliès made one of his most ambitious films: Humanity Through the Ages. This pessimistic film retells the history of humans from Cain and Abel to the Hague Peace Conference of 1907. The film was unsuccessful, yet Méliès was proud of it throughout his life.

Early in 1909, Méliès presided over the "Congrès International des éditeurs de films" in Paris. Under Méliès’ chairmanship, the European congress took place from 2 to 4 February 1909. In his mémoires, Méliès says that this congress was the second one, following the 1908 congress. In 1909, the congress made important decisions regarding film leasing, and adoption of a single type of film perforation, in order to thwart Edison and the MPPC. Like others, Méliès was unhappy with the monopoly that Edison had created and wanted to fight back. The members of the congress agreed to no longer sell films, but to lease them for four-month periods only to members of their own organization, and to adopt a standardized film perforation count on all films. Méliès was unhappy about the second of the three conditions, because his principal clients were owners of fairgrounds and music halls. A fairground trade journal quoted Méliès as saying, "I am not a corporation; I am an independent producer."

Méliès resumed filmmaking in the autumn of 1909 and produced nine films, including Whimsical Illusions, in which he presents a magical effect on stage. At the same time, Gaston Méliès had moved the Méliès Manufacturing Company to Fort Lee, New Jersey. In 1910, Gaston established the Star Film Ranch, a studio in San Antonio, Texas, where he began to produce Westerns. By 1911, Gaston had renamed his branch of Star Films American Wildwest Productions, and opened a studio in southern California. He produced over one hundred thirty films between 1910 and 1912, and he was the primary source for fulfilling Star Films' obligation to Thomas Edison's company. Between 1910 and 1912, Georges Méliès produced very few films.

In 1910, Méliès temporarily stopped making films as he preferred to create a big magic show Les Fantômes du Nil, and go on a very expansive tour in Europe and North Africa. Later that year, Star Films signed an agreement with the Gaumont Film Company to distribute all of its films. But in the autumn of 1910, Méliès made a deal with Charles Pathé that would eventually destroy his own film career. Méliès accepted a large amount of money to produce films and in exchange Pathé Frères would distribute and reserve the right to edit these films. Pathé also held the deed to both Méliès' home and his Montreuil studio as part of the deal. Méliès immediately began production on more elaborate films and the two that he produced in 1911 were Baron Munchausen's Dream and The Diabolical Church Window. Despite the extravagance of these féeries that had been extremely popular just a decade before, both films failed financially.

In 1912, Méliès continued making ambitious films, most notably with the féerie The Conquest of the Pole. Although inspired by such contemporary events as Robert Peary's expedition to the North Pole in 1909 and Roald Amundsen's expedition to the South Pole in 1911, the film also included such fantastic elements as a griffith-headed aerobus and a snow giant that was operated by twelve stage hands, as well as elements reminiscent of Jules Verne and some of the same "fantastic voyage" themes as A Trip to the Moon and The Impossible Voyage. Unfortunately, Conquest of the Pole was not profitable, and Pathé decided to exercise its right to edit Méliès's films from then on.

One of Méliès' last féeries was Cinderella or the Glass Slipper, a fifty-four-minute retelling of the Cinderella legend, shot with new deep focus lenses, outdoors instead of against theatrical backdrops. Pathé hired Méliès's longtime rival Ferdinand Zecca to trim the film to thirty three minutes, and it too was unprofitable. After similar experiences with The Knight of the Snows and The Voyage of the Bourrichon Family in late 1912, Méliès broke his contract with Pathé.

Meanwhile, Gaston Méliès had taken his family and a film crew of over twenty people to Tahiti in the summer of 1912. For the rest of that year and well into 1913, he traveled throughout the South Pacific and Asia, and sent film footage back to his son in New York. The footage was often damaged or otherwise unusable, and Gaston was no longer able to fulfill Star Films' obligation to Thomas Edison's company. By the end of his travels, Gaston Méliès had lost $50,000 and had to sell the American branch of Star Films to Vitagraph Studios. Gaston eventually returned to Europe and died in 1915. He and Georges Méliès never spoke to one another again.

When Méliès broke his contract with Pathé in 1913, he had nothing with which to cover his indebtedness to that company. Although a moratorium declared at the onset of war in 1914 prevented Pathé from taking possession of his home and Montreuil studio, Méliès was bankrupt and unable to continue making films. In his memoirs, he attributes what Miriam Rosen describes as "his own inability to adapt to the rental system" with Pathé and other companies, his brother Gaston's poor financial decisions, and the horrors of World War I as the main reasons that he stopped making movies. The final crisis was the death of Méliès' first wife, Eugénie Génin, in May 1913, leaving him alone to raise their twelve-year-old son, André. The war shut the Théâtre Robert-Houdin for a year, and Méliès left Paris with his two children for several years.

In 1917, the French army turned the main studio building at his Montreuil property into a hospital for wounded soldiers. Méliès and his family then turned the second studio set into a theatrical stage and performed over 24 revues there until 1923. During the war, the French army confiscated over four hundred of Star Films' original prints and melted them down to recover silver and celluloid, the latter of which the army used to make heels for shoes.

In 1923, the Théâtre Robert-Houdin was torn down to rebuild the Boulevard Haussmann. That same year Pathé was finally able to take over Star Films and the Montreuil studio. In a rage, Méliès burned all of the negatives of his films that he had stored at the Montreuil studio, as well as most of the sets and costumes. As a result, many of his films do not exist today. Nonetheless, just over two hundred Méliès films have been preserved, and have been available on DVD since December 2011.

Rediscovery and final years

Méliès was largely forgotten and financially ruined by December 1925, when he married his long-time mistress, the actress Jehanne d'Alcy. The couple scraped together a living by working at a small candy and toy stand d'Alcy owned in the main hall of the Gare Montparnasse.

Around the same time, the gradual rediscovery of Méliès's career began. In 1924, the journalist Georges-Michel Coissac managed to track him down and interview him for a book on cinema history. Coissac, who hoped to underline the importance of French pioneers to early film, was the first film historian to demonstrate Méliès's importance to the industry. In 1926, spurred on by Coissac's book, the magazine Ciné-Journal located Méliès, now working at the Gare Montparnasse, and commissioned a memoir from him. By the late 1920s, several journalists had begun to research Méliès and his life's work, creating new interest in him. As his prestige began to grow in the film world, he was given more recognition and in December 1929, a gala retrospective of his work was held at the Salle Pleyel. In his memoirs, Méliès said that at the event he "experienced one of the most brilliant moments of his life."

Eventually Georges Méliès was made a Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur, the medal of which was presented to him in October 1931 by Louis Lumière. Lumière himself said that Méliès was the "creator of the cinematic spectacle." However, the enormous amount of praise that he was receiving did not help his livelihood or decrease his poverty. In a letter written to French filmmaker Eugène Lauste, Méliès wrote that "luckily enough, I am strong and in good health. But it is hard to work 14 hours a day without getting my Sundays or holidays, in an icebox in winter and a furnace in summer."

In 1932, the Cinema Society arranged a place for Méliès, his granddaughter Madeleine and Jeanne d'Alcy at La Maison de Retraite du Cinéma, the film industry's retirement home in Orly. Méliès was greatly relieved to be admitted to the home and wrote to an American journalist: "My best satisfaction in all is to be sure not to be one day without bread and home!" In Orly, Méliès worked with several younger directors on scripts for films that never came to be made. These included a new version of Baron Munchausen with Hans Richter and a film that was to be titled Le Fantôme du métro (Phantom of the Metro) with Henri Langlois, Georges Franju, Marcel Carné and Jacques Prévert. He also acted in a few advertisements with Prévert in his later years.

Langlois and Franju had met Méliès in 1935 with René Clair, and in 1936, rented an abandoned building on the property of the Orly retirement home to store their collection of film prints. They then entrusted the key to the building to Méliès and he became the first conservator of what would eventually become the Cinémathèque Française. Although he was never able to make another film after 1912 or stage another theatrical performance after 1923, he continued to draw, write to and advise younger film and theatrical admirers until the end of his life.

By late 1937, Méliès had become very ill and Langlois arranged for him to be admitted to the Léopold Bellan Hospital in Paris. Langlois had become close to him, and he and Franju visited him shortly before his death. When they arrived, Méliès showed them one of his last drawings of a champagne bottle with the cork popped and bubbling over. He then told them: "Laugh, my friends. Laugh with me, laugh for me, because I dream your dreams." Georges Méliès died of cancer on 21 January 1938 at the age of 76—just hours after the passing of Émile Cohl, another great French film pioneer—and was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Georges Méliès para niños

In Spanish: Georges Méliès para niños