George Washington in the American Revolution facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

George Washington in the American Revolution

|

|

|---|---|

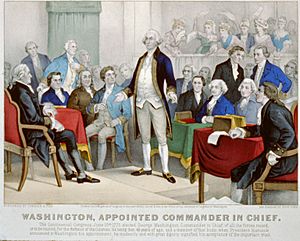

Currier and Ives depiction of Washington accepting his Continental Army commission from the Second Continental Congress

|

|

| Born | February 22, 1732 |

| Died | December 14, 1799 (aged 67) |

| Service/ |

Continental Army |

| Years of service | 1775–1783 |

| Rank | General & Commander in chief |

| Commands held | Main Army |

| Battles/wars | Boston campaign

New York and New Jersey campaign

|

| Awards | General of the Armies (posthumous promotion) |

| Other work | President of the United States |

George Washington (February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799) commanded the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783). After serving as President of the United States (1789 to 1797), he briefly was in charge of a new army in 1798.

Washington, despite his youth, played a major role in the frontier wars against the French and Indians in the 1750s and 1760s. He played the leading military role in the American Revolution. When the war broke out with the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, Congress appointed him the first commander-in-chief of the new Continental Army on June 14. The task he took on was enormous, balancing regional demands, competition among his subordinates, morale among the rank and file, attempts by Congress to manage the army's affairs too closely, requests by state governors for support, and an endless need for resources with which to feed, clothe, equip, arm, and move the troops. He was not usually in command of the many state militia units.

In the early years of the war Washington was often in the middle of the action, first directing the Siege of Boston to its successful conclusion, but then losing New York City and almost losing New Jersey before winning surprising and decisive victories at Trenton and Princeton at the end of the 1776 campaign season. At the end of the year in both 1775 and 1776, he had to deal with expiring enlistments, since the Congress had only authorized the army's existence for single years. With the 1777 establishment of a more permanent army structure and the introduction of three-year enlistments, Washington built a reliable cohort of experienced troops, although hard currency and supplies of all types were difficult to come by. In 1777 Washington was again defeated in the defense of Philadelphia, but sent critical support to Horatio Gates that made the defeat of Burgoyne at Saratoga possible. Following a difficult winter at Valley Forge and the entry of France into the war in 1778, Washington followed the British army as it withdrew from Philadelphia back to New York, and fought an ultimately inconclusive battle at Monmouth Court House in New Jersey.

Washington's activities from late 1778 to 1780 were more diplomatic and organizational, as his army remained outside New York, watching Sir Henry Clinton's army that occupied the city. Washington strategized with the French on how best to cooperate in actions against the British, leading to ultimately unsuccessful attempts to dislodge the British from Newport, Rhode Island and Savannah, Georgia. His attention was also drawn to the frontier war, which prompted the 1779 Continental Army expedition of John Sullivan into upstate New York. When General Clinton sent the turncoat General Benedict Arnold to raid in Virginia, Washington began to detach elements of his army to face the growing threat there. The arrival of Lord Cornwallis in Virginia after campaigning in the south presented Washington with an opportunity to strike a decisive blow. Washington's army and the French army moved south to face Cornwallis, and a cooperative French navy under Admiral de Grasse successfully disrupted British attempts to control of the Chesapeake Bay, completing the entrapment of Cornwallis, who surrendered after the Siege of Yorktown in October 1781. Although Yorktown marked the end of significant hostilities in North America, the British still occupied New York and other cities, so Washington had to maintain the army in the face of a bankrupt Congress and troops that were at times mutinous over conditions and pay. The army was formally disbanded after peace in 1783, and Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief on December 23, 1783.

Resignation and post-war career

Washington's contribution to victory in the war was not that of a great battlefield tactician. He has been characterized, according to historian Edward G. Lengel, in many different ways: "charismatic hero, master of guerrilla warfare, incompetent or infallible battlefield commander, strategic genius, nationalist visionary, fanatical micromanager, and lucky dog". Although he has frequently been said to engage in the Fabian strategy of wearing his opponent down, the truth is more nuanced. On a number of occasions his subordinates convinced him to hold off on plans of attack they saw as rash. Washington only really adopted a Fabian strategy between late 1776 and the middle of 1777, after losing New York City and seeing much of his army melt away. Trenton and Princeton were Fabian examples. By August 1777, however, Washington had rebuilt his strength and his confidence and stopped using raids and went for large-scale confrontations, as at Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth and Yorktown.

Washington is often characterized as complaining about undisciplined militia forces, but he understood that they were a vital part of the nation's defenses, since regular army troops could not be everywhere. He was also at times critical of the mercenary spirit and "the dearth of public spirit" that often underlay difficulties in recruiting for the army.

One of Washington's important contributions as commander-in-chief was to establish the precedent that elected civilian officials, rather than military officers, possessed ultimate authority over the military. Throughout the war, he deferred to the authority of Congress and state officials, and he relinquished his considerable military power once the fighting was over. This principle was especially visible in his handling of the Newburgh conspiracy, and in his "Farewell Orders". The latter document was written at his final wartime headquarters, a house on the outskirts of Princeton owned by the widow Berrien (later to be called Rockingham), but was sent to be read to the assembled troops at West Point on November 2. At Fraunces Tavern in New York City on December 4, he formally bade his officers farewell. On December 23, 1783, Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief to the Congress of the Confederation at Annapolis, Maryland, and retired to his home at Mount Vernon. Washington also became the first President General of the Society of the Cincinnati.

After the war Washington chaired the Constitutional Convention that drafted the United States Constitution, and was then elected the first President of the United States, serving two terms. He briefly engaged in additional military service during a threatened war with France in 1798, and died in December 1799. He is widely recognized as the "Father of his country".

In 2012, a poll conducted by the British National Army Museum recognized Washington as "Britain's Greatest Military Enemy." He beat out Atatürk, Irish independence hero Michael Collins, Erwin Rommel, and Napoleon.

Images for kids

-

Washington was in the vanguard of British forces that occupied Fort Duquesne, recently abandoned by the French, in 1758.

-

Washington at the Battle of Monmouth.

-

Washington Crossing the Delaware, by Emanuel Leutze, 1851.