George Fletcher Moore facts for kids

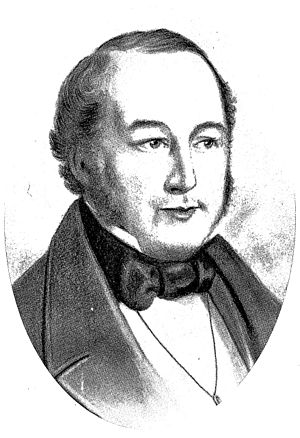

George Fletcher Moore (10 December 1798 – 30 December 1886) was a prominent early settler in colonial Western Australia, and "one [of] the key figures in early Western Australia's ruling elite" (Cameron, 2000). He conducted a number of exploring expeditions; was responsible for one of the earliest published records of the language of the Australian Aborigines of the Perth area; and was the author of Diary of Ten Years Eventful Life of an Early Settler in Western Australia.

Early life

Moore was born on 17 December 1798 at Bond's Glen, Donemana, County Tyrone, Ireland. He was educated at Foyle College in Derry, and at Trinity College in Dublin. He graduated in law in 1820, and spent the next six years at the Irish Bar, but seeing little prospect of advancement he decided to pursue a judicial career in the colonies. Moore enquired at the Colonial Office after an official posting to the recently established Swan River Colony in Western Australia, but was told that such appointments were the responsibility of the Governor of Western Australia, Sir James Stirling, and could not be guaranteed by the Colonial Office. However, the Colonial Office promised him a letter of introduction should he choose to emigrate.

In Australia

Moore sailed from Dublin bound for Western Australia on board the Cleopatra, arriving at the Swan River Colony on 30 October 1830. He then learned that William Mackie had been appointed Chairman of the Courts of Petty and Quarter Sessions in the previous December, effectively eliminating any chances of an official judicial appointment for Moore. He therefore turned his attention to the problems of obtaining his land grant and establishing a farm. By the end of November, Moore had claimed a large area of land in the Avon Valley, which he had not yet seen but had been highly recommended by Robert Dale, who had explored the area in July. Moore also obtained half of William Lamb's grant in Upper Swan by agreeing to undertake the improvements necessary to secure the entire title.

In September 1831, Robert Dale led a large party in cutting a road from Guildford to the Avon Valley. Eager to see his grant for the first time, Moore joined the party. On arriving at the intended site for the town of York, Moore and Dale explored much of the Avon River, correctly guessing that the Avon and the Swan were in fact the same river. The information Moore gathered on this expedition guided him in relocating his inland grant to an area with vastly better pasture land.

In February 1832, Moore finally obtained the judicial appointment he had hoped for, being appointed a Commissioner of the Civil Court. With good land and a regular salary, Moore rapidly consolidated his position as a leading farmer. By 1833 he had one of the largest flocks of sheep in the colony.

Moore was unusual amongst his contemporaries in that he developed friendly, lasting relationships with the Indigenous Australians of the area. As he learned more of their culture, his interest deepened, and he began to take a scholarly interest in their language and customs. In the middle of 1833, Moore published in the Perth Gazette the first account of the customs of the Aborigines of the area. He advocated compensating the natives for the loss of their land, and also promoted the idea of Christianising them. For a while he funded Robert Lyon in his attempt to learn their language, then set out to learn it himself.

Between 1834 and 1836, Moore went exploring a number of times. In January 1834, he explored up the Swan River, finally confirming the belief that the Swan and Avon were the same river. In April 1835, he discovered extended pastoral land near the Garban River, which was subsequently renamed the Moore River. In March 1836, he explored the land between the Moore River and the northern end of the Avon River. In October 1836, he joined a party under John Septimus Roe, which explored inland in the hopes of finding an inland sea, finding instead extremely arid land.

In 1834, A collection of Moore's letters to family in England were published under the title Extracts from the Letters and Journals of George Fletcher Moore Esq., Now Filling a Judicial Office at the Swan River Settlement. The publication was at the request of Moore's father Joseph Moore, and George Fletcher Moore may have been unaware of the publication for some time afterwards.

In July of the same year, Moore's judicial position was handed over to Mackie, and Moore was instead appointed Advocate-General. Moore was initially very upset about his re-appointment, because of the loss of social status in changing from a judge to a lawyer. His new position, however, accorded him a seat on the colony's Legislative Council, and was therefore a position of great influence. Moore took a dislike to many of Governor Stirling's policies, and opposed him on a number of measures. In particular, from March 1835 he continually opposed Stirling's proposal to raise a troops of mounted police to protect against attack by natives.

Early in 1839, John Hutt took office as governor. He shared Moore's interest in the language of the Aborigines, and shortly after his arrival the two of them commenced a project to produce a dictionary of the Aboriginal language. By August 1840 the dictionary was largely complete. Moore took extended leave in March 1841, returning to London for two years. In 1842, Moore's dictionary was published under the title A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia.

Moore returned to Western Australia in 1843, when the Swan River Colony was in a severe recession. Over the next few years, he vigorously opposed a number of proposed measures intended to soften the effects of the recession on leading land holders. Moore claimed that most of the large land holders that were facing economic ruin had been brought to that position through mismanagement. His hard line made many influential enemies, and his popularity plummeted. His views began to attract ridicule both in the Legislative Council and in the press, but he remained influential as he had the confidence of successive governors John Hutt and Andrew Clarke.

On 29 October 1846, Moore married Fanny, stepdaughter of Governor Clarke. In the final months of 1846, both the Governor and Colonial Secretary Peter Broun were seriously ill. As son-in-law of the Governor, Moore was one of a few persons allowed access to the Governor by his doctors. Because of this substantial advantage, Moore was appointed acting colonial secretary in November 1846. Broun died that same month, and Clarke died in February 1847, but Moore continued acting in the position until the arrival of the new colonial secretary, Richard Madden, in March 1848.

Under the acting governorship of Frederick Irwin, Moore's popularity waned further. The government of Irwin and Moore was extremely unpopular; Battye (1924) writes "every administrative act was viewed with suspicion. ... Long years of depression and struggle had made the colonists pessimistic, and ... they threw the blame on the Government of the day." The eventual appointments of Madden and the new governor, Charles Fitzgerald, left Moore with almost no influence in the new government.

Later life and death

Early in 1852, Moore took leave and returned to Ireland. His claimed reason for taking leave was to visit his sick father, but Cameron (2000) states that his chief reason was concern for the mental health of his wife. Her condition deteriorated in Ireland, and she refused to return to Western Australia. Moore was forced to resign his seat; his request for a pension was denied. Fanny Moore died in 1863, but Moore still did not return to Western Australia.

In about 1878, the editor of The West Australian, Sir Thomas Cockburn Campbell, sought and was granted permission to serialise Moore's letters. The letters appeared in the West Australian in 1881 and 1882. On seeing them in print, Moore decided to republish them in book form. They were published in 1884 as Diary of Ten Years Eventful Life of an Early Settler in Western Australia.

Moore died in his London apartment on 30 December 1886. Stannage (1978) writes that he died "apparently friendless", and Cameron (2000) adds "it was a sad end to a worthwhile colonial career."