Ernest J. King facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

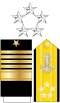

Fleet admiral

Ernest J. King

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Nickname(s) | "Ernie" "Rey" |

| Born | 23 November 1878 Lorain, Ohio, US |

| Died | 25 June 1956 (aged 77) Kittery, Maine, US |

| Buried |

United States Naval Academy Cemetery

|

| Service/ |

United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1901–1956 |

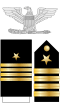

| Rank | Fleet Admiral |

| Commands held | Chief of Naval Operations United States Fleet United States Atlantic Fleet USS Lexington Naval Station Norfolk USS Wright USS Bridge Naval Postgraduate School USS Terry |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

|

| Other work | President, Naval Historical Foundation |

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was an American naval officer who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. As COMINCH-CNO, he directed the United States Navy's operations, planning, and administration and was a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He was the United States Navy's second most senior officer in World War II after Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, who served as Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief.

Born in Lorain, Ohio, King served in the Spanish–American War while still attending the United States Naval Academy. He received his first command in 1914, leading the destroyer USS Terry in the occupation of Veracruz. During World War I, he served on the staff of Vice-Admiral Henry T. Mayo, the commander of the United States Atlantic Fleet. After the war, King served as head of the Naval Postgraduate School, commanded a submarine squadron, and served as Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics. After a period on the Navy's General Board, King became commander of the Atlantic Fleet in February 1941.

Shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, King was appointed as Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet. In March 1942, King succeeded Harold Stark as Chief of Naval Operations. In December 1944, King became the second admiral to be promoted to fleet admiral. King left active duty in December 1945 and died in 1956.

Contents

Early life

King was born in Lorain, Ohio, the son of James Clydesdale King and Elizabeth Keam King. King graduated from what is now Lorain High School as valedictorian in the Class of 1897; his commencement speech was entitled "Values of Adversity". King attended the United States Naval Academy from 1897 until 1901, graduating fourth in his class. During his senior year at the academy, he attained the rank of midshipman lieutenant commander, the highest midshipman ranking at that time. One of his Naval Academy classmates was Vice Admiral William S. Pye.

Surface ships

While still at the Naval Academy, King served on the cruiser USS San Francisco during the Spanish–American War. After graduation, he served as a junior officer on the survey ship USS Eagle, the battleships USS Illinois, USS Alabama and USS New Hampshire, and the cruiser USS Cincinnati.

King returned to shore duty at Annapolis in 1912. He received his first command, the destroyer USS Terry in 1914, participating in the United States occupation of Veracruz. He then moved on to a more modern destroyer, USS Cassin.

During World War I, King served on the staff of Vice-Admiral Henry T. Mayo, the Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet. As such, he was a frequent visitor to the Royal Navy and occasionally saw action as an observer on board British ships. It appears that his Anglophobia developed during this period, although the reasons are unclear. He was awarded the Navy Cross "for distinguished service in the line of his profession as assistant chief of staff of the Atlantic Fleet." It was after World War I that King adopted his signature manner of wearing his uniform with a breast-pocket handkerchief under his ribbons (see image, top right). Officers serving alongside the Royal Navy did this in emulation of Admiral David Beatty. King was the last to continue this tradition.

After the war, King, now a captain, became head of the Naval Postgraduate School. Along with Captains Dudley Wright Knox and William S. Pye, King prepared a report on naval training that recommended changes to naval training and career paths. Most of the report's recommendations were accepted and became policy.

Submarines

Before World War II, King served in the surface fleet. From 1923 to 1925, he held several posts associated with submarines. As a junior captain, the best sea command he was able to secure in 1921 was the stores ship USS Bridge. The relatively new submarine force offered the prospect of advancement.

King attended a short training course at the Naval Submarine Base New London before taking command of a submarine division, flying his commodore's pennant from USS S-20. He never earned his Submarine Warfare insignia (dolphins), although he did propose and design the now-familiar dolphin insignia. In 1923, he took over command of the Submarine Base itself. During this period, he directed the salvage of USS S-51, earning the first of his three Navy Distinguished Service Medals.

Aviation

In 1926, Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer), asked King if he would consider a transfer to naval aviation. King accepted the offer and took command of the aircraft tender USS Wright with additional duties as senior aide on the staff of Commander, Air Squadrons, Atlantic Fleet.

That year, the United States Congress passed a law (10 USC Sec. 5942) requiring commanders of all aircraft carriers, seaplane tenders, and aviation shore establishments be qualified naval aviators or naval aviation observers. King therefore reported to Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida, for aviator training in January 1927. He was the only captain in his class of 20, which also included Commander Richmond K. Turner. King received his wings as Naval Aviator No. 3368 on 26 May 1927 and resumed command of Wright. For a time, he frequently flew solo, flying to Annapolis for weekend visits with his family, but his solo flying was eliminated by a naval regulation prohibiting solo flights for aviators aged 50 or over. However, the history chair at the Naval Academy from 1971 to 1976 disputes this assertion, stating that after King soloed, he never flew alone again. His biographer described his flying ability as "erratic" and quoted the commander of the squadron with which he flew as asking him if he "knew enough to be scared?" Between 1926 and 1936 he flew an average of 150 hours annually.

King commanded Wright until 1929, except for a brief interlude overseeing the salvage of USS S-4. He then became Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics under Moffett. The two quarreled over certain elements of Bureau policy, and he was replaced by Commander John Henry Towers and transferred to command of Naval Station Norfolk.

On 20 June 1930, King became captain of the carrier USS Lexington—then one of the largest aircraft carriers in the world—which he commanded for the next two years. During his tenure aboard the Lexington, King was the commanding officer of science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein, then Ensign Heinlein, prior to his medical retirement from the US Navy. During that time, Ensign Heinlein dated one of King's daughters.

In 1932, King attended the Naval War College.

Following the death of Admiral Moffet in the crash of the airship USS Akron on 4 April 1933, King became Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, and was promoted to rear admiral on 26 April 1933. As bureau chief, King worked closely with the chief of the Bureau of Navigation, Rear Admiral William D. Leahy, to increase the number of naval aviators.

At the conclusion of his term as bureau chief in 1936, King became Commander, Aircraft, Base Force, at Naval Air Station North Island, California. After surviving the crash of his Douglas XP3D transport on 8 February 1937, he was promoted to vice-admiral on 29 January 1938 on becoming Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force – at the time one of only three vice-admiral billets in the US Navy. Among his accomplishments was to corroborate Admiral Harry E. Yarnell's 1932 war game findings in 1938 by staging his own successful simulated naval air raid on Pearl Harbor, showing that the base was dangerously vulnerable to aerial attack, although he was taken no more seriously than his contemporary until December 7, 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the base by air for real.

King hoped to be appointed as either Chief of Naval Operations or Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, but on 15 June 1939, he was posted to the General Board, an elephants' graveyard where senior officers spent the time remaining before retirement. A series of extraordinary events would alter this outcome.

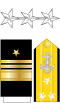

World War II

King's career was resurrected by his friend, Admiral Harold "Betty" Stark, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) who realized King's talent for command was being wasted on the General Board. Stark appointed him Commander, Atlantic Squadron, in 1940. In December 1940 King said the US was already at war with Germany. King was promoted to admiral in February 1941 as Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANT). On 30 December, he became Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH). (Admiral Husband Kimmel held this position during the attack on Pearl Harbor.) On 18 March 1942, King was appointed CNO, relieving Stark, becoming the only officer to hold this combined command. After turning 64 on 23 November 1942, he wrote President Franklin D. Roosevelt to say he had reached mandatory retirement age. Roosevelt replied with a note reading, "So what, old top?". In January 1941 King issued Atlantic Fleet directive Cinclant Serial 053, encouraging officers to delegate and avoid micromanagement, which is still cited widely in today's armed forces.

Historian Michael Gannon blamed King for the heavy American losses during the Second Happy Time. Others however blamed the belated institution of a convoy system, partly due to a severe shortage of suitable escort vessels, without which convoys were seen as more vulnerable than lone ships. King has been heavily criticized for ignoring British advice regarding convoys and up-to-date British intelligence on U-boat operations in the Atlantic, leading to high losses among the US Merchant Marine.

On 17 December 1944, King was promoted to the newly created rank of fleet admiral, the second of four men in the U.S. Navy to hold that rank during World War II. He left active duty on 15 December 1945, but officially remained in the Navy, as five-star officers were to be given active duty pay for life. On the same day that King left active duty, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz succeeded him as Chief of Naval Operations.

Retirement and death

After retiring, King lived in Washington, D.C. He was active in his early post-retirement, serving as president of the Naval Historical Foundation from 1946 to 1949, and he wrote the foreword to and assisted in the writing of Battle Stations! Your Navy In Action, a photographic history book depicting the U.S. Navy's operations in World War II that was published in 1946. King suffered a debilitating stroke in 1947, and subsequent ill-health ultimately forced him to stay in naval hospitals at Bethesda, Maryland, and at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine. King briefly served as an advisor to the Secretary of the Navy in 1950, but he was unable to return to duty in any long-term capacity as his health would not permit it. King wrote an autobiography, Fleet Admiral King: A Naval Record, which he published in 1952.

King died of a heart attack in Kittery on 25 June 1956, at the age of 77. After lying in state at the National Cathedral in Washington, King was buried in the United States Naval Academy Cemetery at Annapolis, Maryland. His wife, who survived him, was buried beside her husband in 1969.

Personal life

While at the Naval Academy, King met Martha Rankin ("Mattie") Egerton, a Baltimore socialite, whom he married in a ceremony at the Chapel at West Point on 10 October 1905. King and Egerton had six daughters, Claire, Elizabeth, Florence, Martha, Eleanor and Mildred; and a son, Ernest Joseph King, Jr. Ernest Jr also served in navy, retiring at the rank of Commander. King was a practicing Episcopalian, a faith he shared with his wife and made a point of raising all of their children in.

Dates of rank

- Midshipman – June 1901

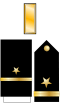

| Ensign | Lieutenant (junior grade) | Lieutenant | Lieutenant Commander | Commander | Captain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1 | O-2 | O-3 | O-4 | O-5 | O-6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 7 June 1903 | Never Held | 7 June 1906 | 1 July 1913 | 1 July 1917 | 21 September 1918 |

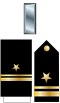

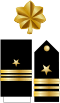

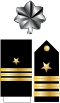

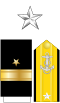

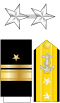

| Rear Admiral (lower half) | Rear Admiral | Vice Admiral | Admiral | Fleet Admiral |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-7 | O-8 | O-9 | O-10 | Special Grade |

|

|

|

|

|

| Never Held | 26 April 1933 | 29 January 1938 | 1 February 1941 | 17 December 1944 |

King never held the rank of lieutenant (junior grade) although, for administrative reasons, his service record annotates his promotion to both lieutenant (junior grade) and lieutenant on the same day.

- All dates of rank were referenced from Master of Sea Power: A Biography of Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, pp. xii–xv.

Awards and decorations

|

|||

| Naval Aviator Wings | |||

| Navy Cross | Navy Distinguished Service Medal with two stars |

Sampson Medal | |

| Spanish Campaign Medal | Philippine Campaign Medal | Mexican Service Medal | World War I Victory Medal with "Atlantic Fleet" clasp |

| American Defense Service Medal with "A" Device |

American Campaign Medal | World War II Victory Medal | National Defense Service Medal |

Foreign awards

King was also the recipient of several foreign awards and decorations (shown in order of acceptance and if more than one award for a country, placed in order of precedence):

| Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (United Kingdom) 1945 | |

| Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur (France) 1945 | |

| Grand Cross of the Order of George I (Greece) 1946 | |

| Knight Grand Cross with Swords of the Order of Orange-Nassau (Netherlands) 1948 | |

| Knight of the Grand Cross of the Military Order of Italy 1948 | |

| Order of Naval Merit (Brazil), Grand Officer 1943 | |

| Estrella Abdon Calderon (Ecuador) 1943 | |

| Grand Officer of the Order of the Crown with palm (1948) | |

| Commander of the Order of Vasco Núñez de Balboa (Panama) 1929 | |

| Officer of the Order of the Crown of Italy 1933 | |

| Order of Naval Merit (Cuba) 1943 | |

| Order of the Sacred Tripod (China) 1945 | |

| Croix de guerre (France) 1944 (attachment(s) unknown) | |

| Croix de Guerre (Belgium) (1948) (attachment(s) unknown) |

Legacy

- The guided missile destroyer USS King was named in his honor.

- Two public schools in his hometown of Lorain, Ohio, have been named after him: (Admiral King High School) until it was merged with the city's other public high school to form Lorain High School in 2010, and Admiral King Elementary School.

- In 2011, Lorain dedicated a Tribute Space at Admiral King's birthplace, and new elementary school in Lorain will bear his name.

- In 1956, schools located on the U.S. Naval Bases and Air Stations were given names of U.S. heroes of the past. E.J. King High School, the Department of Defense high school on Sasebo Naval Base, in Japan, is named for him.

- The dining hall at the U.S. Naval Academy, King Hall, is named after him.

- The auditorium at the Naval Postgraduate School, King Hall, is also named after him.

- Recognizing King's great personal and professional interest in maritime history, the Secretary of the Navy named in his honor an academic chair at the Naval War College to be held with the title of the Ernest J. King Professor of Maritime History.

- King Drive at Arlington National Cemetery is named in honor of Fleet Admiral King.

- One of the two major living quarters at Officer Training Command, Newport, RI is named King Hall in his honor.

- King was portrayed by Tyler McVey in The Gallant Hours, Russell Johnson in MacArthur (1977 film), John Dehner in War and Remembrance (miniseries), and Mark Rolston in Midway (2019 film)

See also

In Spanish: Ernest J. King para niños

In Spanish: Ernest J. King para niños