Eochaid (son of Rhun) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Eochaid |

|

|---|---|

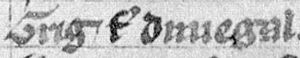

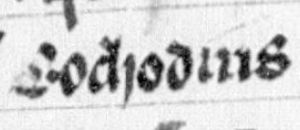

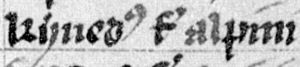

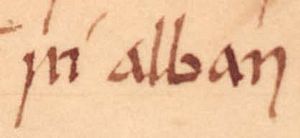

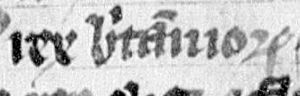

Eochaid's name as it appears on folio 29r of Paris Bibliothèque Nationale Latin 4126 (the Poppleton manuscript): "Eochodius".

|

|

| Issue |

|

| Father | Rhun ab Arthgal |

Eochaid (fl. 878–889) was a ninth-century Briton who may have ruled as King of Strathclyde and/or King of the Picts. He was a son of Rhun ab Arthgal, King of Strathclyde, and descended from a long line of British kings. Eochaid's mother is recorded to have been a daughter of Cináed mac Ailpín, King of the Picts. This maternal descent from the royal Alpínid dynasty may well account for the record of Eochaid reigning over the Pictish realm after the death of Cináed's son, Áed, in 878. According to various sources, Áed was slain by Giric, a man of uncertain ancestry, who is also accorded kingship after Áed's demise.

It is uncertain if Eochaid and Giric were relatives, unrelated allies, or even rivals. Whilst it is possible that they held the Pictish kingship concurrently as allies, it is also conceivable that they ruled successively as opponents. Another possibility is that, whilst Giric reigned as King of the Picts, Eochaid reigned as King of Strathclyde. Eochaid's floruit dates about the time when the Kingdom of Strathclyde seems to have expanded southwards into lands formerly possessed by the Kingdom of Northumbria. The catalyst for this extension of British influence appears to have been the Viking conquest of this northern English realm.

According to various sources, Eochaid and Giric were driven from the kingship in 889. The succeeding king, Domnall mac Custantín, was an Alpínid, and could well have been responsible for the forced regime change. The terminology employed by various sources suggests that during the reigns of Eochaid and Giric, or during that of Domnall and his successors, the wavering Pictish kingdom—weakened by political upheaval and Viking invasions—redefined itself as a Gaelic realm: the Kingdom of Alba.

Eochaid is not attested after 889. Likewise, nothing is recorded of the Kingdom of Strathclyde until the first quarter of the next century, when a certain Dyfnwal, King of Strathclyde is reported to have died. Whilst the parentage of this man is unknown, it is probable that he was a member of Eochaid's kindred, and possibly a descendant of him. A daughter of Eochaid may have been Lann, a woman recorded to have been the mother of Muirchertach mac Néill, King of Ailech.

Contents

Sources of the royal succession

It is uncertain who assumed the kingship of Strathclyde after Rhun. If Rhun and Custantín both died in 876, Eochaid could well have succeeded his father. Certainly, Custantín's brother, Áed mac Cináeda, succeeded as King of the Picts, and ruled as such upon his death two years later. Whilst the Annals of Ulster reports that Áed was killed by his own companions, several mediaeval king-lists state that he was slain by a certain Giric. Quite who reigned as king after Áed is uncertain, although there are several plausible possibilities.

According to the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba, Eochaid succeeded Áed, and held the kingship for eleven years. The chronicle adds that it was further said that Giric also reigned during this period on account of the fact that he was Eochaid's alumnus ("foster father", "guardian") and ordinator ("guardian", "governor", or "king-maker"). A solar eclipse is also noted during their reigns—an event dated to the feast of St Ciricius—and the two are stated to have been ejected from the kingdom.

The chronicle reports that Áed Findliath mac Néill died in the second year of Eochaid's reign. Since Áed indeed expired in 879, the chronicle's chronology is evidently accurate for the outset of Eochaid's reign. As for the eclipse, the chronicle appears to place it in the context of the final year of Eochaid's kingship. Nevertheless, it is clear that the eclipse is identical to that which took place on 16 June 885, as 16 June is certainly the feast day of at least one saint named Ciricius. Since the dates given by the chronicle and the Annals of Ulster show that there was an eleven-year gap between the previous reign and the next, it is evident that the eclipse indeed occurred in the midst of Eochaid's reign. The chronicle's inconsistency in regard to the eclipse may owe itself to an attempt to increase the dramatic effect of the regime change by associating a remarkable astronomical event with Eochaid's expulsion.

Other than the chronicle, the only source to associate both Eochaid and Giric as kings is the twelfth-century Prophecy of Berchán. According to the latter, Eochaid ruled as king for thirteen years until he was expelled and succeeded by Giric (described as "the son of fortune"). The discrepancies between the two sources may partly stem from an ethnic bias. Certainly, the Prophecy of Berchán is critical of Eochaid's British heritage whilst Giric is celebrated as a Scot.

Relationship with Giric

Giric's familial origins are uncertain. According to several versions of the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba his father's name was Dúngal, whereas certain versions of the Verse Chronicle equate his father's name to Domnall. Although it is possible that Giric's association with kingship stems from an ancestral claim, the evidence for this is uncertain. Giric need not have possessed any claim of his own, and could have merely played the role of kingmaker, by orchestrating the removal of Áed, and installing Eochaid in his place.

Nevertheless, there is also reason to suspect that Giric's patronym, "son of Dúngal", may actually refer to an early form of the Welsh Dyfnwal rather than the Gaelic Dúngal. If correct, Giric's patronym could be evidence that his father was Dyfnwal ap Rhydderch, King of Al Clud, and that Giric was a brother of Arthgal. Such a relationship could indicate that Giric's apparent killing of Áed was undertaken in the context of avenging Arthgal's demise at Custantín's behest. If Giric and Eochaid were indeed both descendants of Dyfnwal, Eochaid could well have ruled as king under the tutelage of Giric, his granduncle.

Giric's patronym may instead identify him as a son of Domnall mac Ailpín. If such a parentage is correct, it would certainly mean that Giric possessed a strong claim to the Pictish throne. The fact that Áed seems to have succeeded Custantín could indicate that Giric had been denied the kingship. Such a possibility could account for Giric's apparent killing of Áed. It could also reveal that Giric received or was reliant upon significant assistance from Eochaid—in this case his maternal kinsman—which would in turn account for the evidence that Giric and Eochaid shared the Pictish kingship in some manner.

Conversely, it could have been Eochaid who claimed the kingship by right of his maternal Alpínid ancestry. If this was indeed the case, one possibility is that Eochaid was only able to hold authority in conjunction with Giric—either as an ally or client, or perhaps as a youthful ward under Giric's guardianship. In the ninth century, the term ordinator was used to describe the relationship between a powerful ruler and a satellite. One such example is the establishment of Bran mac Fáeláin as King of Leinster by Niall Caille mac Áeda, King of Tara. As such, the terminology employed by the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba could reveal that Giric—as ordinator—similarly established Eochaid as king.

It is conceivable that Eochaid ruled over both the Strathclyde Britons and Picts. If so, he could have initiated his royal career as King of Strathclyde before succeeding as King of the Picts. In fact, the evidence of shared kingship may merely mean that Eochaid ruled the British kingdom whilst Giric ruled the Pictish realm. As such, it is possible that Giric was successful in imposing some form of authority over the Kingdom of Strathclyde during Eochaid's floruit. If correct, the price for Eochaid's assistance may have been the preservation of the British realm from other descendants of Cináed. The fact that Eochaid's grandfather died in 872 could indicate that, if his father died soon after, Eochaid may have succeeded to the kingship of Strathclyde as a youth.

The remarkable uncertainty surrounding the Pictish kingship during this period means that it is also possible that Eochaid and Giric were rivals rather than allies. An adversarial relationship between the two may well be evidenced by the Prophecy of Berchán which gives a negative account of the Britons during Giric's tenure.

Expansion of the British realm

It is not until the turn of the tenth century before sources cast light upon the history of the Kingdom of Strathclyde. At some point after the loss of Al Clud, the Kingdom of Strathclyde appears to have undergone a period of expansion. Although the precise chronology is uncertain, by 927 the southern frontier appears to have reached the River Eamont, close to Penrith. The catalyst for this southern extension may have been the dramatic decline of the Kingdom of Northumbria at the hands of conquering Scandinavians, and the expansion may have been facilitated by cooperation between the Cumbrians and insular Scandinavians in the late ninth- and early tenth centuries. Amiable relations between these powers may be evidenced by the remarkable collection of contemporary Scandinavian-influenced sculpture at Govan. There is reason to suspect that Eochaid reigned during this expansion of the Kingdom of Strathclyde. The Pictish and British realms are certainly not recorded to have been assailed by Vikings during Eochaid's floruit. Furthermore, a union of the Pictish and British kingdoms could well have allowed him to extend British authority southward.

Transformation of the Pictish realm

As for the Scottish kingdom, the succeeding king is identified as Domnall mac Custantín by the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba. Domnall's kingship is corroborated by the Annals of Ulster and Chronicon Scotorum which report his death in 900. The fact the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba accords Domnall an eleven-year reign places the inception of his rule in 889, and therefore corroborates the eleven-year reign accorded to Eochaid. Domnall is the first monarch to be styled King of Alba by a contemporary annalistic source. Prior to about this period, the Gaelic Alba stood for "Britain". In fact, the shifting terminology employed by various English, Irish, and Scottish sources may be evidence that the Pictish realm underwent a radical transformation during this period in history.

For example, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle identifies the Irish as Scottas up until the 890s. By the 920s, this term came to be accorded to the people formerly regarded as Pictish (and last recorded as such in the 870s). As for the Irish annals—specifically the hypothesised Chronicle of Ireland—the terms Picti and rex Pictorum ("king of the Picts") are last accorded to the Picts and their kings in the 870s. In fact, the last Pictish king to be styled thus was Domnall's uncle, Áed. By the 900s, the terms fir Alban ("men of Alba") and rí Alban ("king of Alba") are utlilised for these people. The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba last utilises the term Pictavia in the midst of Domnall's reign. Thereafter, the realm is called Albania.

There is reason to suspect that the political and dynastic upheaval endured by the Pictish realm in the last quarter of the ninth century was the catalyst for a radically new political order based upon the reestablishment of the Alpínids in the kingship. Alternately, the transformation could have taken place specifically during the floruit of Giric and Eochaid. For instance, it is conceivable that Giric gained the throne by seizing upon the upheaval caused by the incessant Viking depredations that assailed Pictavia. At an earlier date, the Gaelic realm of Dál Riata appears to have crumbled under such pressures, and it is possible that Giric drew military power from this broken polity to forcefully seize the Pictish throne. In any case, the accommodation of significant Gaelic aristocratic power in the wavering Pictish realm could account for the eventual transformation of Pictavia into Alba.

The temporary exclusion of the Alpínids from the Pictish throne could well have meant that they endured exile in Ireland. Certainly, Domnall's paternal aunt, Máel Muire ingen Cináeda, possessed significant Irish connections as the wife of two successive kings of Tara—Áed Findliath and Flann Sinna mac Maíl Shechnaill—and the mother of another—Niall Glúndub mac Áeda. If Domnall and his succeeding first cousin, Custantín mac Áeda, indeed spent their youth in Ireland prior to assuming the kingship of Alba, their Gaelic upbringing could well have ensured the continuation of Pictavia's Gaelicisation. If the eventual Alpínid successors of Eochaid and Giric were indeed sheltered in Ireland, this could account for the fact that the Chronicle of Ireland fails to acknowledge their usurpation.

Furthermore, if the Pictish transformation indeed stems from the floruit of Giric and Eochaid, the new terminology could indicate that the Kingdom of Alba was envisioned to include Pictish, Gaelic, British, and English inhabitants. Several king-lists allege that Giric subjugated Ireland and England during his reign, an outlandish claim that could instead evince a multi-ethnic northern alliance under his authority. As such, there is reason to suspect that Alba—a term previously used for Britain—may have been meant to encapsulate a new political construction, a polity of "North Britain".

Legacy

Although the apparent reigns of Eochaid and Giric are obscure and uncertain, Giric eventually came to remembered as a legendary figure, credited as the liberator of the Gaelic Church from the Picts, and the architect of military conquests of Ireland and England. Eochaid, on the other hand, is only attested by the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba and the Prophecy of Berchán. Unlike Giric, later mediaeval king-lists and chronicles fail to include Eochaid within their accounts of Scottish history. In fact, Eochaid, and the later Alpínid Amlaíb mac Illuilb, King of Alba, are the only Scottish kings not noted by the king-lists. The window within which Eochaid and Giric appear to have reigned marks the only point between the careers of Cináed and Máel Coluim mac Cináeda, King of Alba that a patrilineal Alpínid is not known to have ruled the Pictish/Alban realm.

Eochaid is unattested after his apparent expulsion in 889, and the date of his death is unrecorded and unknown. According to various king-lists, Giric was slain at Dundurn. Evidence of extensive burning at the site may relate to this event, and may mark the end of the fort's use. If the accounts of Giric's downfall are to be believed, and if both he and Eochaid were allied together at the time, it is conceivable that both Eochaid and Giric fell together. Alternately, Giric's killing could have contributed to Eochaid's ejection from the kingship. Although it is unknown who was responsible for Giric's reported demise, one candidate is the succeeding Domnall. Alternately, Domnall's path to throne could have been paved by magnates who afterwards sent for him.

Certainly, nothing is recorded concerning the kingship of Strathclyde until the turn of the tenth century, when the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba notes the passing of a certain Dyfnwal, King of Strathclyde. Dyfnwal's parentage is uncertain. On one hand, he could have been another son of Rhun. On the other hand, he could have been descended from Eochaid: either as a son or grandson. Alternately, Dyfnwal could have represented a more distant branch of the same dynasty. Eochaid may have also had a daughter, Lann, the wife of Niall Glúndub attested by the Great Book of Lecan version of the twelfth-century Banshenchas. As such, if the Banshenchas is to be believed, a maternal grandson of Eochaid was Lann's son, Muirchertach mac Néill.

See also

In Spanish: Eochaid de Escocia para niños

In Spanish: Eochaid de Escocia para niños

- Máel Coluim, son of the king of the Cumbrians, a probable member of Eochaid's kindred who could have reigned as either King of Strathclyde or King of Alba