Emmett Till facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Emmett Till

|

|

|---|---|

Till in a photograph taken by his mother on Christmas Day 1954

|

|

| Born |

Emmett Louis Till

July 25, 1941 |

| Died | August 28, 1955 (aged 14) Money, Mississippi U.S.

|

| Cause of death | Homicide |

| Resting place | Burr Oak Cemetery |

| Education | James McCosh Elementary School |

| Parent(s) | Mamie Carthan Till-Mobley Louis Till |

Emmett Louis Till (July 25, 1941 – August 28, 1955) was a 14-year-old African American boy murdered in Mississippi on August 28, 1955, after accusations that he had offended a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, in her family's grocery store. Till's murder and the fact that his killers were acquitted drew attention to the long history of violent persecution of African Americans in the United States. Till posthumously became an icon of the civil rights movement.

Contents

Early childhood

Emmett Till was born in 1941 in Chicago; he was the son of Mamie Carthan (1921–2003) and Louis Till (1922–1945). Emmett's mother Mamie was born in the small Delta town of Webb, Mississippi. The Delta region encompasses the large, multi-county area of northwestern Mississippi in the watershed of the Yazoo and Mississippi rivers. When Carthan was two years old, her family moved to Argo, Illinois, near Chicago, as part of the Great Migration of rural black families out of the South to the North to escape violence, lack of opportunity and unequal treatment under the law. Argo received so many Southern migrants that it was named "Little Mississippi"; Carthan's mother's home was often used by other recent migrants as a way station while they were trying to find jobs and housing.

Mississippi was the poorest state in the U.S. in the 1950s, and the Delta counties were some of the poorest in Mississippi. Mamie Carthan was born in Tallahatchie County, where the average income per white household in 1949 was $690 (equivalent to $7,000 in 2016). For black families, the figure was $462 (equivalent to $4,700 in 2016). In the rural areas, economic opportunities for blacks were almost nonexistent. They were mostly sharecroppers who lived on land owned by whites. Blacks had essentially been disenfranchised and excluded from voting and the political system since 1890 when the white-dominated legislature passed a new constitution that raised barriers to voter registration. Whites had also passed ordinances establishing racial segregation and Jim Crow laws.

Mamie largely raised Emmett with her mother; she and Louis Till separated in 1942.

At the age of six, Emmett contracted polio, which left him with a persistent stutter. Mamie and Emmett moved to Detroit, where she met and married "Pink" Bradley in 1951. Emmett preferred living in Chicago, so he returned there to live with his grandmother; his mother and stepfather rejoined him later that year. After the marriage dissolved in 1952, "Pink" Bradley returned alone to Detroit.

Plans to visit relatives in Mississippi

In 1955, Mamie Till Bradley's uncle, 64-year-old Mose Wright, visited her and Emmett in Chicago during the summer and told Emmett stories about living in the Mississippi Delta. Emmett wanted to see for himself. Wright planned to accompany Till with a cousin, Wheeler Parker; another cousin, Curtis Jones, would join them soon. Wright was a sharecropper and part-time minister who was often called "Preacher". He lived in Money, Mississippi, a small town in the Delta that consisted of three stores, a school, a post office, a cotton gin, and a few hundred residents, 8 miles (13 km) north of Greenwood. Before Emmett departed for the Delta, his mother cautioned him that Chicago and Mississippi were two different worlds, and he should know how to behave in front of whites in the South. He assured her he understood.

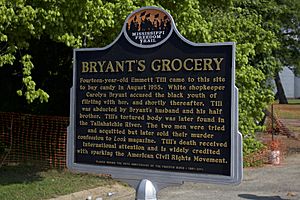

Encounter between Till and Carolyn Bryant

Till arrived in Money, Mississippi, on August 21, 1955. On August 24, he and cousin Curtis Jones skipped church where his great-uncle Mose Wright was preaching and joined some local boys as they went to Bryant's Grocery and Meat Market to buy candy. The teenagers were children of sharecroppers and had been picking cotton all day. The market mostly served the local sharecropper population and was owned by a white couple, 24-year-old Roy Bryant and his 21-year-old wife Carolyn. Carolyn was alone in the front of the store that day; her sister-in-law was in the rear of the store watching children. Jones left Till with the other boys while Jones played checkers across the street.

The facts of what took place in the store are still disputed. According to some versions, including comments from some of the youngsters standing outside the store, Till may have whistled at Bryant. Till's cousin, Simeon Wright, who was with him at the store, stated that Till whistled at Bryant, saying, "I think [Emmett] wanted to get a laugh out of us or something," adding, "He was always joking around, and it was hard to tell when he was serious." Wright stated that following the whistle he became immediately alarmed. "Well, it scared us half to death," Wright recalled. "You know, we were almost in shock. We couldn't get out of there fast enough, because we had never heard of anything like that before. A black boy whistling at a white woman? In Mississippi? No." Wright stated "The Ku Klux Klan and night riders were part of our daily lives". Following his disappearance, a newspaper account stated that Till sometimes whistled to alleviate his stuttering. His speech was sometimes unclear; his mother said he had particular difficulty with pronouncing "b" sounds, and he may have whistled to overcome problems asking for bubble gum. She said that, to help with his articulation, she taught Till how to whistle softly to himself before pronouncing his words.

Till's interaction with Bryant, perhaps unwittingly, violated the unwritten code of behavior for a black male interacting with a white female in the Jim Crow-era South.

Several nights after the incident in the store, Bryant's husband, Roy, and his half-brother J.W. Milam, who were armed, went to Till's great-uncle's house and abducted Emmett. The men took the boy to the barn where he was murdered.

Trial

The trial was held in the county courthouse in Sumner, the western seat of Tallahatchie County. Sumner had one boarding house; the small town was besieged by reporters from all over the country. David Halberstam called the trial "the first great media event of the civil rights movement". A reporter who had covered the trials of Bruno Hauptmann and Machine Gun Kelly remarked that this was the most publicity for any trial he had ever seen.

Bryant and Milam were acquitted of Till's murder. They were not charged with his kidnapping.

Newspapers in major international cities and religious, and socialist publications reported outrage about the verdict and strong criticism of American society. Southern newspapers, particularly in Mississippi, wrote that the court system had done its job. Till's story continued to make the news for weeks following the trial, sparking debate in newspapers, among the NAACP and various high-profile segregationists about justice for blacks and the propriety of Jim Crow society.

A few months after the trial, protected against double jeopardy, Bryant and Milam admitted murdering Till in an interview given to Look magazine. Neither of the men believed they were guilty or that they had done anything wrong.

Reaction to the interview with Bryant and Milam was explosive. Their brazen admission that they had murdered Till caused prominent civil rights leaders to push the federal government harder to investigate the case. Till's murder contributed to congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957: it authorized the U.S. Department of Justice to intervene in local law enforcement issues when individual civil rights were being compromised.

See also

In Spanish: Emmett Till para niños

In Spanish: Emmett Till para niños