Earth oven facts for kids

An earth oven, ground oven or cooking pit is one of the simplest and most ancient cooking structures. At its most basic, an earth oven is a pit in the ground used to trap heat and bake, smoke, or steam food. Earth ovens have been used in many places and cultures in the past, and the presence of such cooking pits is a key sign of human settlement often sought by archaeologists. Earth ovens remain a common tool for cooking large quantities of food where no equipment is available. They have been used in various civilizations around the world and are still commonly found in the Pacific region to date.

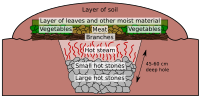

To bake food, the fire is built, then allowed to burn down to a smoulder. The food is then placed in the oven and covered. This covered area can be used to bake bread or other various items. Steaming food in an earth oven covers a similar process. Fire-heated rocks are put into a pit and are covered with green vegetation to add moisture and large quantities of food. More green vegetation and sometimes water are then added, if more moisture is needed. Finally, a covering of earth is added over everything. The food in the pit can take up to several hours to a full day to cook, regardless of the dry or wet method used.

Today, many communities still use cooking pits for ceremonial or celebratory occasions, including the indigenous Fijian lovo, the Hawaiian imu, the Māori hāngi, the Mexican barbacoa, and the New England clambake. The central Asian tandoor use the method primarily for uncovered, live-fire baking, which is a transitional design between the earth oven and the horizontal-plan masonry oven. This method is essentially a permanent earth oven made out of clay or firebrick with a constantly burning, very hot fire in the bottom.

Contents

Americas

In many areas, archaeologists recognize "pit-hearths" as being commonly used in the past. In Central Texas, there are large "burned-rock middens" speculated to be used for large-scale cooking of plants of various sorts, especially the bulbs of sotol. The Mayan pib and Andean watia are other examples. In Mesoamerica and the Caribbean nations, barbacoa is a common practice. Barbacoa, originally a Taino word referring to the pit itself, consists of slow-roasted meat in a maguey-lined pit, popular in Mexico alongside birria, tortillas, and salsa.

The clambake, invented by Native Americans on the Atlantic seaboard and considered a traditional element of New England cuisine, traditionally uses a type of ad hoc earth oven (usually built on a beach). A large hole is dug into the sand and heated rocks are added to the bottom of the hole. A layer of seaweed is then laid on top to create moisture and steam, followed by the food. Finally, another layer of seaweed is added to trap in the steam and cook the food, which mainly consists of shellfish and vegetables.

The curanto of the Chiloé Archipelago consists of shellfish, meat, potatoes, milcao chapaleles, and vegetables traditionally prepared in an earth oven. It has spread to the southern areas of Chile.

The huatia or watia and pachamanca are traditional earth ovens of the Andean regions of Peru, Bolivia, and Chile. They are both indigenous practices that pre-date the Inca Empire.

Asia

The Hakka of China that live in tulou have been known to use earth ovens to cook.

Middle East and North Africa

Earth oven cooking is sometimes used for celebratory cooking in North Africa, particularly Morocco: a whole lamb is cooked in an earth oven (called a tandir, etymologically related to the Central- and South-Asian tandoor and possibly descended from an Akkadian word tinuru) in a manner similar to the Hawaiian kalua. Among Bedouin and Tuareg nomads, a simple earth oven is used – often when men travel without family or kitchen equipment in the desert. The oven is mostly used to bake bread but is also used to cook venison and waran. When baking bread, the wheat or barley flour is mixed with water and some salt and then placed directly into the hot sands beneath the camp fire. It is then covered again by hot coal and left to bake. This kind of bread is eaten with black tea (in the absence of labneh). The sand has to be knocked off carefully before consuming the bread. Sometimes this type of bread is also made when the family is together, because people like the taste of it. The bread is often mixed with molten fat (sometimes oil or butter) and labneh (goat milk yoghurt) and then formed into a dough before eating. This bread is known as Arbut but may be known under other local names.

Pacific and Madagascar

Earth oven cooking was very common in the past and continues into the present – particularly for special occasions, since the earth oven process is very labor-intensive.

In some part-Melanesian, Polynesian, and other closely related languages, the general term is "umu," from the Proto-Oceanic root *qumun (e.g. Tongan ʻumu, Māori umu or hāngi, Hawaiian imu, Sāmoan umu, Cook Island Māori umu). In some non-Polynesian, part-Polynesian, and Micronesian parts of the Pacific, which some islands use the similar word umu, but not all Micronesian islands having many different languages use that base word umu, however, other words are used instead of umu - in Fiji it is a lovo, in Rotuman it is a koua and in Tahiti, it is a ahima'a.

In Papua New Guinea, "mumu" is used by Tok Pisin and English speakers, but each of the other hundreds of local languages has its own word. In the Solomon Islands the word in Pidgin is Motu.

Despite the similarities, there are many differences in the details of preparation, their cultural significance, and current usage. Earth ovens are said to have originated in Papua New Guinea and have been adopted by the later arriving Polynesians.

Samoan umu

The Samoan umu uses the same method of cooking as many other earth ovens and is closely related to the Hawaiian earth oven, the imu, which is made underground by digging a pit (although generally the umu is done above ground rather than in a pit). It is a common day-to-day method of preparing roasted foods, with modern ovens being restricted to western-style houses. In the traditional village house, gas burners will be used inside the house to cook some food in pots. The umu is sheltered by a roof in case of rain, and it is separate from the house. There are no walls, which allows the smoke from the umu to escape.

The Samoan umu starts with a fire to heat rocks which have been tested by fire as to whether they will explode upon heating. These rocks are used repeatedly but eventually are discarded and replaced when it is felt that they no longer hold enough heat. Once the rocks are hot enough, they are stacked around the parcels of food which are wrapped in banana leaves or aluminium foil. Leaves are then placed over the assembly and the food is left to cook for a few hours until it is fully cooked.

Hawaiian imu

The Hawaiian imu was the easiest way to cook large quantities of food quickly and efficiently for the Hawaiians. Because their creation was so labor-intensive, imus were only created for special events or ceremonies where it would be worth the time and hard work. An imu is created by first digging a 2- to 4-foot hole in the ground. Porous rocks are heated for a while and subsequently added to the bottom of the pit; next, a layer of banana stumps is added on top of them along with banana leaves. After the vegetation is laid down, the meat, fish, and any other foods are placed on top and covered once again with more vegetation. Wet cocoa sacks are also sometimes added on top to add even more moisture and trap in more heat.

Europe

In Europe, earth ovens were used from the Neolithic period onward, with examples from this period found at the sites of Rinyo and Links of Notland on Orkney, but are more commonly known in the Bronze and Iron Ages from sites such as Trethellan Farm, Newquay and Maiden Castle, Dorset, and in Scandinavia. Many pot boilers from British prehistoric sites are now considered to be the by-product of cooking with stones, in something similar to a Polynesian oven. Examples from the European prehistoric vary in form but are generally bowl-shaped and shallow in depth (30–45 cm), with diameters between 0.5 and 2 metres.

Exceptions do exist, such as the Irish Fulacht fiadh, in common use up to the Middle Ages. In Greek cuisine, there is also a tradition of kleftiko ("thief style") dishes, ascribed to anti-Turkish partisans during the Greek War of Independence, which involve wrapping the food in clay and cooking it in a covered pit, allegedly at first to avoid detection by Turkish forces.

See also

In Spanish: Horno de tierra para niños

In Spanish: Horno de tierra para niños