Denis Healey facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Lord Healey

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

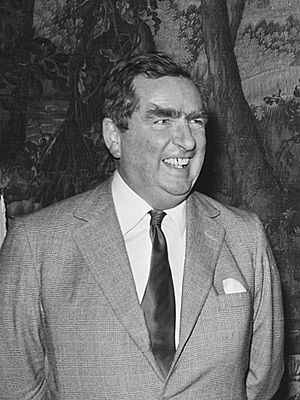

Healey in 1974

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy Leader of the Labour Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 4 November 1980 – 2 October 1983 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader | Michael Foot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Michael Foot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Roy Hattersley | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 4 March 1974 – 4 May 1979 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Anthony Barber | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Geoffrey Howe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secretary of State for Defence | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 16 October 1964 – 19 June 1970 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Peter Thorneycroft | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | The Lord Carrington | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Denis Winston Healey

30 August 1917 Mottingham, Kent, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 3 October 2015 (aged 98) Alfriston, Sussex, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | St Andrew's Church | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Labour | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Edna Edmunds

(m. 1945; |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | British Army | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1940–1945 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Major | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit | Royal Engineers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards | Member of the Order of the British Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Denis Winston Healey, Baron Healey, CH, MBE, PC, FRSL (30 August 1917 – 3 October 2015) was a British Labour politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1974 to 1979 and as Secretary of State for Defence from 1964 to 1970; he remains the longest-serving Defence Secretary to date. He was a Member of Parliament from 1952 to 1992, and was Deputy Leader of the Labour Party from 1980 to 1983. To the public at large, Healey became well known for his bushy eyebrows, his avuncular manner and his creative turns of phrase.

Healey attended the University of Oxford and served as a Major in the Second World War. He was later an agent for the Information Research Department, a secret branch of the Foreign Office dedicated to spreading anti-communist propaganda during the early Cold War. Healey was first elected to Parliament in a by-election in 1952 for the seat of Leeds South East. He moved to the seat of Leeds East at the 1955 election, which he represented until his retirement at the 1992 election.

After Labour's victory at the 1964 election, he was appointed to the Cabinet by Prime Minister Harold Wilson as Defence Secretary; he held this role until Labour's defeat at the 1970 election, making him the longest-serving Secretary of State for Defence to date. When Labour returned to power after the 1974 election, Wilson appointed Healey Chancellor of the Exchequer. He stood for the leadership of the Labour Party in the election to replace Wilson in March 1976, but lost to James Callaghan; Callaghan retained Healey as Chancellor in his new government. During his time as Chancellor, Healey notably sought out an international loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for the British economy, which imposed external conditions on public spending.

Healey stood a second time for the leadership of the Labour Party in November 1980, but narrowly lost to Michael Foot. Foot immediately chose Healey as his Deputy Leader, but after the Labour Party agreed a series of changes to the rules governing leadership elections, Tony Benn launched a challenge to Healey for the role; the election was bitterly contested throughout most of 1981, and Healey was able to beat the challenge by less than 1%. Standing down as Deputy Leader after Labour's landslide defeat at the 1983 election, Healey remained in the Shadow Cabinet until 1987, and entered the House of Lords soon after his retirement from Parliament in 1992. Healey died in 2015 at the age of 98, having become the oldest sitting member of the House of Lords, and the last surviving member of Harold Wilson's first government formed in 1964.

Contents

Early life

Denis Winston Healey was born in Mottingham, Kent, but moved with his family to Keighley in the West Riding of Yorkshire at the age of five. His parents were Winifred Mary (née Powell; 1889–1988) and William Healey (1886–1977). His middle name honoured Winston Churchill.

Healey had one brother, Terence Blair Healey (1920–1998), known as Terry. His father was an engineering mechanic who worked his way up from humble origins, winning an engineering scholarship to Leeds University and qualifying to teach engineering, eventually becoming head of Keighley Technical School. His paternal grandfather was a tailor from Enniskillen in Northern Ireland.

Healey's family often spent the summer in Scotland during his youth.

Education

Healey received early education at Bradford Grammar School. In 1936 he won an exhibition scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford, to read Greats. He there became involved in Labour politics, although he was not active in the Oxford Union Society. Also while at Oxford, Healey joined the Communist Party in 1937 during the Great Purge, but left in 1940 after the Fall of France.

At Oxford, Healey met future Prime Minister Edward Heath (then known as "Teddy"), whom he succeeded as president of Balliol College Junior Common Room, and who became a lifelong friend and political rival.

Healey achieved a double first degree, awarded in 1940. He was a Harmsworth Senior Scholar at Merton College, Oxford in 1940.

Second World War

After graduation, Healey served in the Second World War as a gunner in the Royal Artillery before being commissioned as a second lieutenant in April 1941. Serving with the Royal Engineers, he saw action in the North African campaign, the Allied invasion of Sicily (1943) and the Italian campaign (1943–1945) and was the military landing officer ("beach master") for the British assault brigade at Anzio in 1944.

Healey became an MBE in 1945. He left the service with the rank of Major. He declined an offer to remain in the army, with the rank of Lieutenant colonel, as part of the team researching the history of the Italian campaign under Colonel David Hunt. He also decided against taking up a senior scholarship at Balliol, which might have led to an academic career.

Political career

Early career

Healey joined the Labour Party. Still in uniform, he gave a strongly left-wing speech to the Labour Party conference in 1945, declaring, "the upper classes in every country are selfish, depraved, dissolute and decadent" shortly before the general election in which he narrowly failed to win the Conservative-held seat of Pudsey and Otley, doubling the Labour vote but losing by 1,651 votes.

He became secretary of the international department of the Labour Party in 1944, becoming a foreign policy adviser to Labour leaders and establishing contacts with socialists across Europe. He was a strong opponent of the Communist Party of Great Britain at home and the Soviet Union internationally. From 1948 to 1960 he was a councillor for the Royal Institute of International Affairs and the International Institute for Strategic Studies from 1958 until 1961. He was a member of the Fabian Society executive from 1954 until 1961. Healey used his position as the Labour Party's International Secretary to promote the Korean War on behalf of British state propagandists, used British intelligence agencies to attack Marxist leaders within UK trade unions, and to exploit his position in government to publish his books through IRD propaganda fronts.

Healey was one of the leading players in the Königswinter conference that was organised by Lilo Milchsack that was credited with helping to heal the bad memories after the end of the Second World War. Healey met Hans von Herwarth, the ex soldier Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin and future German President Richard von Weizsäcker and other leading West German decision makers. The conference also included other leading British decisionmakers like Richard Crossman and the journalist Robin Day.

Member of Parliament

Healey was elected to the House of Commons as MP for Leeds South East at a by-election in February 1952, with a majority of 7,000 votes. Following constituency boundary changes, he was elected for Leeds East at the 1955 general election, holding that seat until he retired as an MP in 1992.

He was a moderate on the right during the series of splits in the Labour Party in the 1950s. He was a supporter and friend of Hugh Gaitskell. He persuaded Gaitskell to temper his initial support for British military action in 1956 when the Suez Canal was seized by the Nasserist Egypt, resulting in the Suez Crisis. When Gaitskell died in 1963, he was horrified at the idea of Gaitskell's volatile deputy, George Brown, leading Labour, saying "He was like immortal Jemima; when he was good he was very good but when he was bad he was horrid". In the 1963 Labour Party leadership election, he voted for James Callaghan in the first ballot and Harold Wilson in the second. Healey thought Wilson would unite the Labour Party and lead it to victory in the next general election. He didn't think Brown was capable of doing either. He was appointed Shadow Secretary of State for Defence after the creation of the position in 1964.

Defence Secretary

Following Labour's victory in the 1964 general election, Healey served as Secretary of State for Defence under Prime Minister Harold Wilson. He was responsible for 450,000 British Armed Forces uniformed servicemen and women, and for 406,000 civil servants stationed around the globe. He was best known for his economising, liquidating most of Britain's military role outside of Europe, and cancelling expensive projects. The cause was not a fiscal crisis but rather a decision to shift money and priorities to the domestic budget and maintain a commitment to NATO. He cut defence expenditure, scrapping the carrier HMS Centaur and the reconstructed HMS Victorious in 1967, cancelling the proposed CVA-01 fleet-carrier replacement and, just before Labour's defeat in 1970, downgrading HMS Hermes to a commando carrier. He cancelled the fifth planned Polaris submarine. He also cancelled the production of the Hawker Siddeley P.1154 and HS 681 aircraft and, more controversially, both the production of the BAC TSR-2 and subsequent purchase of the F-111 in lieu.

Of the scrapped Royal Navy aircraft carriers, Healey commented that to most ordinary seamen they were just "floating slums" and "too vulnerable". He continued postwar Conservative governments' reliance on strategic and tactical nuclear deterrence for the Navy, RAF and West Germany and supported the sale of advanced arms abroad, including to regimes such as those in Pahlavi Iran, Libya, Chile, and apartheid South Africa, to which he supplied nuclear-capable Buccaneer S.2 strike bombers and approved a repeat order. This brought him into serious conflict with Wilson, who had, initially, also supported the policy. Healey later said he had made the wrong decision on selling arms to South Africa.

In January 1968, a few weeks after the devaluation of the pound, Wilson and Healey announced that the two large British fleet carriers HMS Ark Royal and HMS Eagle would be scrapped in 1972. They also announced that British troops would be withdrawn in 1971 and the British military and navy bases in South East Asia, "East of Aden", closed, large facilities in Malaysia and Singapore and the Persian Gulf and the Maldives. The next Prime Minister Edward Heath slowed the implementation of the policy, with 5/6 frigates on station East of Suez until 1976, when Healey as Chancellor used the IMF crisis to withdraw the Royal Navy frigates attached to the Five Power Defence Arrangements squadron and the Hong Kong Guard frigate, HMS Chichester. Healey also authorised the removal of the Chagossians from the Chagos Archipelago and authorised the building of the United States military base at Diego Garcia. Following Labour's defeat in the 1970 general election, he became Shadow Defence Secretary.

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Healey was appointed Shadow Chancellor in April 1972 after Roy Jenkins resigned in a row over the European Economic Community (Common Market). At the Labour Party conference on 1 October 1973, he said, "I warn you that there are going to be howls of anguish from those rich enough to pay over 75% on their last slice of earnings". In a speech in Lincoln on 18 February 1974, Healey went further, promising he would "squeeze property speculators until the pips squeak." He alleged that Lord Carrington, the Conservative Secretary of State for Energy, had made £10m profit from selling agricultural land at prices 30 to 60 times as high as it would command as farming land. When accused by colleagues including Eric Heffer of putting Labour's chances of winning the next election in jeopardy through his tax proposals, Healey said the party and the country must face the consequences of Labour's policy of the redistribution of income and wealth; "That is what our policy is, the party must face the realities of it".

Healey became Chancellor of the Exchequer in March 1974 after Labour returned to power as a minority government. His tenure is sometimes divided into Healey Mark I and Healey Mark II. The divide is marked by his decision, taken with Prime Minister James Callaghan, to seek an International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan and submit the British economy to IMF supervision. The loan was negotiated and agreed in November and December 1976, and announced in Parliament on 15 December 1976. Within some parts of the Labour Party the transition from Healey Mark I (which had seen a proposal for a wealth tax) to Healey Mark II (associated with government-specified wage control) was regarded as a betrayal. Healey's policy of increasing benefits for the poor meant those earning over £4,000 per year would be taxed more heavily. His first budget saw increases in food subsidies, pensions and other benefits.

When Harold Wilson stood down as Leader of the Labour Party in 1976 Healey stood in the contest to elect the new leader. On the first ballot he came only fifth out of six candidates. However, he also contested the second round, coming third of the three candidates but increasing his vote somewhat.

Deputy Leader of the Labour Party

Labour lost the general election to the Conservatives, led by Margaret Thatcher in May 1979, following the Winter of Discontent during which Britain had faced a large number of strikes. On 12 June 1979 Healey was appointed a Companion of Honour. Healey won the most votes in the 1979 Shadow Cabinet elections which followed and The Glasgow Herald suggested that this showed that he was the "strongest contender" to succeed Callaghan as Leader of the Labour Party.

When Callaghan stood down as Labour leader in November 1980, Healey was the favourite to win the Labour Party leadership election, decided by Labour MPs. In September an opinion poll had found that when asked who would make the best Prime Minister if Healey were Labour leader, 45% chose Healey over 39% for Thatcher. However, he lost to Michael Foot. He seems to have taken the support of the right of the party for granted; in one notable incident, Healey was reputed to have told the right-wing Manifesto Group they must vote for him as they had "nowhere else to go". When Mike Thomas, the MP for Newcastle East defected to the Social Democratic Party (SDP), he said he had been tempted to send Healey a telegram saying he had found "somewhere else to go". Four Labour MPs who defected to the SDP in early 1981 later said they voted for Foot in order to give the Labour Party an unelectable left-wing leader, thus helping their newly established party.

In an essay addressing why Healey did not become Prime Minister (or Labour leader) Steve Richards concedes that in 1980 Healey, not Foot, was widely expected by the media and many political figures to be the next Labour leader. Richards also notes that of by this point his main rivals as potential leaders from the right of the party from 1976 and earlier, Roy Jenkins and Anthony Crosland, were no longer in contention for the position with the former out of parliament and the latter having died in 1977. However he also argues that while "Healey was widely seen as the obvious successor to Callaghan", and that sections of the media ultimately reacted with "disbelief" at Labour not choosing him to be their leader, the decision to opt for Foot "was not as perverse as it seemed". He argues Labour MPs were looking for a figure from the left who could unite the wider party with the leadership which Healey could not do. Richards believes that Foot was not a "tribal politician" and had proved he could work with those of different ideologies and had been a loyal deputy to Callaghan and so came to be "seen as the unity candidate" which allowed him to defeat Healey.

Healey was returned unopposed as deputy leader to Foot, but the next year was challenged by Tony Benn under the new election system, one in which individual members and trades unions voted alongside sitting members of parliament. The contest was seen as a battle for the soul of the Labour Party, and long debate over the summer of 1981 ended on 27 September with Healey winning by 50.4% to Benn's 49.6%. The narrowness of Healey's majority can be attributed to the Transport and General Workers' Union (TGWU) delegation to the Labour Party conference. Ignoring its members, who had shown two-to-one majority support for Healey, it cast the union's block vote (the largest in the union section) for Benn. A significant factor in Benn's narrow loss, however, was the abstention of 20 MPs from the left-wing Tribune Group, which split as a result. Healey attracted just enough support from other unions, Constituency Labour Parties, and Labour MPs to win.

Healey was Shadow Foreign Secretary during most of the 1980s, a job he coveted. He believed Foot was initially too willing to support military action after the Falkland Islands were invaded by Argentina in April 1982. He accused Thatcher of "glorying in slaughter", and had to withdraw the remark (he later claimed he had meant to say "conflict"). Healey was retained in the shadow cabinet by Neil Kinnock, who succeeded Foot following the disastrous 1983 general election, when the Conservatives bolstered their majority and Labour suffered their worst general election result in decades. Healey had declined to run as leader to succeed Foot as well as standing down as deputy leader.

Retirement

His views on nuclear weapons conflicted with the unilateral nuclear disarmament policy of the Labour Party. After the 1987 general election, he retired from the Shadow Cabinet, and in 1992 stood down after 40 years as a Leeds MP. In that year he received a life peerage as Baron Healey, of Riddlesden in the County of West Yorkshire. Healey was regarded by some – especially in the Labour Party – as "the best Prime Minister we never had". He was a founding member of the Bilderberg Group. He was interviewed on his role as a co-founder of the Bilderberg Group by Jon Ronson for the book Them: Adventures with Extremists.

During an interview with Nick Clarke on BBC Radio 4, Healey was the first Labour politician to publicly declare his wish for the Labour leadership to pass to Tony Blair in 1994, following the death of John Smith. Healey later became critical of Blair. He publicly opposed Blair's decision to use military force in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq. In the spring of 2004, and again in 2005, he publicly called on Blair to stand down in favour of Gordon Brown. In July 2006 he argued, "Nuclear weapons are infinitely less important in our foreign policy than they were in the days of the Cold War", and, "I don't think we need nuclear weapons any longer".

In March 2013 during an interview with the New Statesman, Healey said that if there was a referendum on British membership of the EU, he would vote to leave. In May, he further said: "I wouldn't object strongly to leaving the EU. The advantages of being members of the union are not obvious. The disadvantages are very obvious. I can see the case for leaving – the case for leaving is stronger than for staying in".

Following the death of Alan Campbell, Baron Campbell of Alloway, in June 2013, Healey became the oldest sitting member of the House of Lords. Following the death of John Freeman on 20 December 2014, Healey became the surviving former MP with the earliest date of first election, and the second-oldest surviving former MP, after Ronald Atkins.

Public image

Healey's notably bushy eyebrows and piercing wit earned him a favourable reputation with the public.

Personal life and death

Healey married Edna May Edmunds on 21 December 1945, the two having met at Oxford University before the war. The couple had three children, one of whom is the broadcaster and writer Tim Healey. Edna Healey died on 21 July 2010, aged 92. They were married for almost 65 years and lived in Alfriston, East Sussex. In 1987, Edna underwent an operation at a private hospital – this event drawing media attention as being seemingly at odds with Healey's pro-NHS beliefs. Challenged on the apparent inconsistency by the presenter Anne Diamond on TV-am, Healey became critical and ended the interview. He then jabbed journalist Adam Boulton.

Healey was an amateur photographer for many years; he also enjoyed music, painting and reading crime fiction. He sometimes played popular piano pieces at public events. In a May 2012 interview for The Daily Telegraph, Healey reported that he was swimming 20 lengths a day in his outdoor pool. Healey was interviewed in 2012 as part of The History of Parliament's oral history project.

After a short illness Healey died in his sleep at his home in Alfriston, Sussex, on 3 October 2015, at the age of 98. He was buried alongside his wife in the graveyard of St Andrew's Church, Alfriston. In 2017, his personal archives were deposited at the Bodleian Library.

Honours

| Ribbon | Name | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Order of the Companions of Honour | 12 June 1979 | CH | |

| Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire | 13 December 1945 | MBE | |

In 2004, Healey became the recipient of the first Veteran's Badge.

Legacy

Healey is credited with popularising in the UK a proverb which became known as Healey's First law of holes. This is a minor adaptation of a saying often attributed to Will Rogers.