Daniel Brustlein facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Daniel Brustlein ("Alain")

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | September 11, 1904 |

| Died | July 14, 1996 (aged 91) Paris, France

|

| Nationality | Naturalized US |

| Alma mater | École des Arts & Métiers and the École des Beaux-Arts in Geneva, Switzerland |

| Known for | American artist, cartoonist, illustrator, and author of children's books |

Daniel Brustlein (1904–1996) was an Alsatian-born American artist, cartoonist, illustrator, and author of children's books. He is best known for the cartoons and cover art he contributed to The New Yorker magazine under the pen name "Alain" from the 1930s through the 1950s. The novelist John Updike once said his childhood discovery of Brustlein's cartoons helped to stimulate his desire to write for the magazine and one of Brustlein's cartoons has been repeatedly cited for its skillful and witty self-reference. Although they have not received the same public acclaim as his humorous drawings, his paintings drew strong praise from influential critics such as Hilton Kramer, who said Brustlein's work had great refinement showing "beautiful control over the precise emotion he wants it to convey" and "complete command of color and form handled with a remarkable delicacy and discretion." In October 1960 a painting of Brustlein's appeared on the cover of ARTnews and his reputation as a "painter's painter" appeared to be firmly established after he was the subject of an article in that magazine four years later.

Contents

Early life

Daniel Brustlein was born on September 11, 1904, in the Alsatian town of Mulhouse. Although attached to Germany and known as Mülhausen during Brustlein's childhood, the town retained historic ties to France and, despite their unavoidable German citizenship, many of its citizens—Brustlein included—considered themselves to be French. He attended local schools approximately through age fourteen and, showing an early aptitude for drawing, published his first collection of cartoons—Petite Histoire de la Guerre en Caricatures—at the age of fifteen in 1919. At about that time he began residence in Geneva and soon after enrolled as an art student in that city, first at the École des Arts & Métiers and then the École des Beaux Arts. In 1924, at the urging of one of his teachers, Brustlein moved to Paris where he found work as an illustrator while continuing his art studies. Two years later some of his illustrations were included in the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes. The exposition, a World's fair held in Paris from April to October 1925, introduced the Art Deco style.

In 1927 Brustlein moved to New York City on the advice of Jean Coquillot, a colleague and fellow student. Having emigrated from Geneva in 1921, Coquillot had found work in New York as an illustrator, humorous cartoonist, and book cover designer. In the 1930s he would become known for a cover he contributed to Mademoiselle magazine (1936) and illustrations he made for Heidi Grows Up (1938), the first of two sequels to the book Heidi. Through his friendship with Coquillot, Brustlein found work drawing illustrations and cartoons and within a few years he had become a regular contributor to The New Yorker magazine.

Mature style

Brustlein's mature style emerged after he had emigrated to New York and begun working as an illustrator and cartoonist.

Illustrations and cartoons for magazines

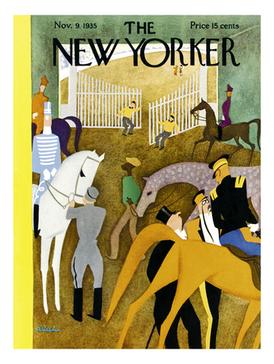

Beginning in the early 1930s his cartoons began to appear in The New Yorker and Collier's magazines. He signed this early work with the name "Alain" and subsequently used that pen name for the rest of his career as illustrator and cartoonist. The issue of The New Yorker for November 9, 1935, contained Brustlein's first cover art. Over the next 30 years he would produce another nine covers for the magazine. In 1936 he illustrated a book entitled Farewell to Model T. Written by New Yorker writer E. B. White and journalist Richard Lee Strout, the book was a reprint of a New Yorker piece of May 16, 1936 entitled "Farewell My Lovely." Both the book and article were credited to the pseudonymous author "Lee Strout White." The book's illustrations were credited to Brustlein as "Alain."

During World War II Brustlein contributed drawings and cartoons to exhibitions benefiting the war effort. In January 1942 he won first prize for a cartoon that appeared in one such exhibition held at the Grand Central Art Galleries. Consisting of nearly 100 posters made by cartoonists and comic strip artists, the show raised money for both United China Relief and U.S. War Bonds. In February of the same year he won a prize at a benefit exhibition of cartoons sponsored by the American Society of Magazine Cartoonists and held at the Art Students League. The show, called "Cartoons Against the Axis," contained 116 works. Brustlein's contribution showed a Japanese husband reading a Japanese newspaper and commenting, "It seems there's a good deal of unrest over there because of priorities and they expect to see internal collapse by Spring." In May the cartoon was shown again in an exhibition called "Cartoons of the day" at the Metropolitan Museum In July Brustlein married the painter Janice Biala. At the close of the war they moved to Paris and, while living there most of the year, retained American citizenship and usually spent some months in the United States.

After the close of World War II Brustlein, as "Alain," continued to make cartoons and cover illustrations for The New Yorker and other magazines, but he produced less of this work in order to devote more time to easel painting and the illustration of children's books. A cartoon he contributed to The New Yorker in 1955 has been cited as a good example of metapictorial drawing. Entitled "Drawing From the Life," the cartoon presents a classroom scene in ancient Egypt where art students are using modern perspective techniques to sketch a model who stands in a stiff, flat pose that is typical of Egyptian art.

Easel painting and other art

Brustlein was a painter and book illustrator as well as a magazine illustrator and cartoonist.

After the close of World War II he continued to place drawings and cartoons in magazines such as The New Yorker, The Saturday Evening Post, Look, and Esquire, but he also began to make paintings for group and solo exhibitions in galleries located in New York, Paris, and other cities. In 1948 and for the next three years he contributed paintings to the Salon des Surindependants in Paris. In 1952 he was given his first solo show when "Peintures de Alain Brustlein" opened at Galerie Jeanne Bucher in Paris. His work also appeared group exhibitions at Stable Gallery in New York and at the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts in Lausanne. In 1952 a French critic included him among the best young painters of the day when reporting his nomination for the Prix de la Critique (Galerie Saint Placide, Paris). In 1955 Stable Gallery gave him his first New York solo exhibition.

In 1957 he contributed work to a group exhibition of portraits held at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery. Apart from Brustlein, the artists, who were not generally known for their portraiture, included Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Philip Guston, Milton Resnick, and Larry Rivers. A year later his paintings appeared in the annual exhibition at the L'École de Paris for the first time and in 1959 he was given a second one-person show at the Stable Gallery. Of the portraits and landscapes he contributed to this show, the critic for the New York Times said "Without pushing realization far he succeeds quite strikingly in compassing characterization in the spontaneous portraits, and with a few quick strokes of the brush establishes mood in low keyed statements of scene."

In 1960 Brustlein received a purchase award at the 5th International Hallmark invitational exhibition held at Wildenstein Gallery in New York. The prize-winning painting, a self-portrait, subsequently appeared on the cover of the October 1960 issue of ARTnews. Four years later his brother-in-law, Jack Tworkov, wrote a feature article on him for the November issue of ARTnews, and that month, his work appeared in a solo exhibition at the Saidenberg Gallery. In 1965 a painting of his was included in a group show of portraits showing friends and acquaintances of the participating artists. Appearing at the New School Art Center, the show drew praise from Stuart Preston of the New York Times for its "delectable items" that "make for extraordinary documentary value."

Through the rest of the decade and into the 1970s Brustlein continued to show at Galerie Lutece, Galerie Jacob, and other Parisian galleries and the Sachs gallery in New York. Of a painting he saw in 1978, the Times critic Hilton Kramer wrote that Brustlein showed "complete command of color and form handled with a remarkable delicacy and discretion." In reviewing a solo exhibition at Sachs the following year Kramer said:

In everything that Daniel Brustlein paints there is a sensibility of great refinement. We are never in any doubt that this is a painter with a deep affection for his medium, and a beautiful control over the precise emotion he wants it to convey. His color is gentle and delicate, and his imagery too—mostly of generalized figures in interior or landscape spaces—has a gentle, pacific quality. It is in the sensitive handling of the medium—in cool greens and blues of "Chinatown," in the copper-haired figure of "Rastro," in the way the couch encloses the three figures in "Ladybug"—that we feel his special felicity as a painter.

Three years later, discussing another solo show at Sachs, a critic praised his "taste for muted colors that may owe something to Paris" and said his oil paint has the pleasing quality of slightly decaying fresco."

During the 1980s he showed at the Gruenebaum gallery in New York and the Galerie Jeanne Bucher in Paris and in the next decade, the last of his life, mostly in the Kouros Gallery, New York.

A retrospective exhibition at Kouros in 1994 pulled together works from his wife and her family as well as his own. Entitled "A Family," it included works by Biala's brother, Jack Tworkov; his daughter, Hermine Ford; her husband, Robert Moskowitz; and Erik Moskowitz who is the son of Hermine and Robert. Other retrospective exhibitions include solo and group shows at Kouros (1997, 1999, 2001, 2002) and group shows at Galerie Jacob (1996) and Galerie Arnaud (Paris, 2001).

Books

Farewell to Model T was Brustlein's only book illustration project of the 1930s and 1940s. In the mid-1950s, Brustlein began to illustrate and also to write books, most of them short and all intended for children's use. In 1956 he wrote and illustrated a book called The Elephant and the Flea in which an elephant tries increasingly desperate measures to dislodge a troublesome flea. That same year he illustrated a book, written by his wife, called It's Spring! It's Spring!. The book describes the transition from winter to spring from the point of view of the chickadees, bluebirds and swallows who then start building nests and sing with a new vigor. A reviewer for the New York Times said Brustlein's drawings were "wonderfully colored," depicting "swirling patterns of birds in flight." The following year Brustlein wrote and illustrated The Magic Stones, a book on the architectural uses of the arch. Introducing an evil character, "Monsieur Down," it explains how medieval builders used the arch to overcome the destructive force he employed, that of gravity, so that they might construct the great Gothic cathedrals of France. The text says "Monsieur Down" was so enraged at being defeated that he turned to stone and is now a great gargoyle, seated high upon Notre Dame de Paris. Writing in The New York Times, C.E. Van Norman said Brustlein employed simple text and clear pictures to produce a fascinating introduction to the subject. In 1959 he illustrated Minette, another book for which his wife supplied the text. The book, which describes the title character's life in a royal palace, drew praise from the New York Times for the quality of its illustrations. In 1968 Brustlein wrote and illustrated a book called One, Two, Three, Going to Sea. Using cartoon figures the book provides an introductory guide to adding and subtracting. A reviewer called it a book both amusing and useful for arithmetic-ready children.

Personal life

Brustlein was born in the town of Mulhouse close to the borders of Germany, France, and Switzerland. At the time of his birth the town was called Mülhausen as it was then part the German Empire, having been ceded by France following her defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. Over many centuries the town was occasionally independent but most often attached to one of its neighboring countries. It had been detached from the Swiss Confederation to become part of France during the French Revolution and, four decades after 1870, it was returned to France following World War I, only to be again taken by Germany during World War II and returned thereafter. When asked to his nationality at birth, Brustlein reported that he was French rather than German.

One of the oldest families in the community, the Brustleins became prominent in the late fifteenth century during a transition from an aristocratic council to a democratic form of government. Thereafter members of the family served frequently as the town's mayor and in 1512 one Martin Brustlein commanded a company of Mulhousiens in successful battles to defend Pope Jules II from attacks by armies of King Louis XII of France. In 1925 the city council named a low-cost public housing project in honor of the Brustlein family.

In 1940 Brustlein told a census taker that he had left school after the eighth grade. This presumably means that he received elementary education in Mulhouse and that he did not graduate from either of the schools he subsequently attended in Geneva (the École des Arts & Métiers and the École des Beaux-Arts). While studying at these schools, Brustlein apparently obtained Swiss citizenship. This seems likely since on emigrating to New York in 1927 the manifest of the ship on which he traveled gave his nationality as Swiss. He emigrated to the New York in 1927 and in 1933 became a U.S. citizen.

The 1940 Census shows that Brustlein was then living in a New York apartment with his mother, Louise. It is possible that she had recently come to live with him since reports of his travels as late as 1939 do not show her as a companion. Louise Brustlein's age is given as 63 and her presumptive year of birth is thus 1877. She would have been about 26 when Brustlein was born. Sometime on or before December 1938 Brustlein met his future wife, Janice Biala, who was then living with Ford Madox Ford. An acquaintance of Ford's remembered meeting Brustlein at a New Year's Eve party she and Ford gave in a Manhattan apartment where they were then staying. The acquaintance wrote that Brustlein, whom she knew only as "Alain," was an Alsatian ("or maybe Luxembourger") with red hair. Brustlein and Biala were both artists, both Francophiles, and both by nature outgoing and sociable. They were friends with many of the same people, mostly in the Parisian and New York art communities. Willem de Kooning, then a struggling young artist, became a close friend whom Brustlein and Biala would nurse when ill and to whom Brustlein would provide financial support. Two years later, on July 11, 1942, Brustlein and Biala married in New York and the following year they hosted a wedding lunch for de Kooning and his new wife Elaine, herself an artist. They lived in New York during the war years and, while retaining U.S. citizenship, in 1947 they moved to Paris where they reunited with friends in the artist community.

In 1949 Brustlein and Biala began renting places in Gladstone, New Jersey, during their periodic returns to the United States and in 1953 they purchased a farmhouse in the Peapack area of Gladstone, New Jersey. That year de Kooning insisted that Brustlein join the members-only club that he and other artists of the New York School had founded to discuss topics related to the art movement which would become known as abstract expressionism.

Brustlein was 92 years old when he died on July 14, 1996. His obituary in The New York Times referred to him as a "painter's painter" whose work was aligned with the School of Paris. His wife survived him by four years, dying at the age of 97 on September 24, 2000.

Images for kids