Craigenputtock facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Craigenputtock House and Estate |

|

|---|---|

| Native name The Craig | |

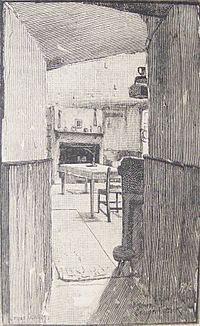

Painting by George Moir 1829

|

|

| Location | Dumfries and Galloway |

| Area | 800 acres (324 ha) |

| First occupied | 15th century |

| Built | 18th century (completed) |

| Built for | The family of Welsh |

| Current residents | Carter-Campbell of Possil |

| Architectural style(s) | Georgian |

|

Listed Building – Category B

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

Craigenputtock (usually spelled by the Carlyles as Craigenputtoch) is an estate in Scotland where Thomas Carlyle lived from 1828 to 1834. He wrote several of his early works there, including Sartor Resartus.

The estate's name incorporates the Scots words craig, meaning hill, referring in this case to a whinstone hill, and puttock, or small hawk. Craigenputtock occupies 800-acre (3.2 km2) of farmland in the civil parish of Dunscore in Dumfriesshire, within the District Council Region of Dumfries and Galloway. The principal residence on the grounds is a two-storey, four bedroomed Georgian Country House (category B listed). The estate also comprises two cottages, a farmstead, 315 acres (127 ha) of moorland hill rising to 1,000 ft (300 m) above sea level, and 350 acres (140 ha) of inbye ground of which 40 acres (16 ha) is arable, ploughable land and 135 acres (55 ha) is woodland.

It was the property for generations (circa 1500) of the family Welsh, and eventually that of their heiress, Jane Baillie Welsh Carlyle (1801–1866) (descended on the paternal side from Elizabeth, the youngest daughter of John Knox), which the Carlyles made their dwelling-house in 1828, where they remained for seven years (before moving to Carlyle's House in Cheyne Row, London), and where Sartor Resartus was written. The property was bequeathed by Thomas Carlyle to the Edinburgh University on his death in 1881. It is now home to the Carter-Campbell family, and managed by the C.C.C. (Carlyle Craigenputtock Circle).

Carlyle, painting by Whistler

|

It is certain that for living and thinking in, I have never since found in the world a place so favourable. How blessed might poor mortals be in the straitest circumstances if their wisdom and fidelity to heaven and to one another were adequately great!

—Thomas Carlyle on Craigenputtock

Picture gallery

-

Watercolor by Helen Allingham of the rear view of Craigenputtock in 1891

-

Photograph taken in 2008 of the pulpit stone at Craigenputtock. Used by the covenanters in the 1600s for secret prayer meetings.

-

Painting by artist Christine Lovelock (daughter of the Gaia Theorist James Lovelock) view of Craigenputtock from the east in 2006

-

Painting by artist Christine Lovelock (daughter of the Gaia Theorist James Lovelock) view of Craigenputtock from the south in 2006

James Paterson on Craigenputtock

Our Eaves at Craigenputtock

Thou too hast travell'd, little fluttering thing—

Hast seen the world, and now thy weary wing

Thou too must rest.

But much, my little bird, couldst thou but tell,

I 'd give to know why here thou lik'st so well

To build thy nest.

For thou hast pass'd fair places in thy flight;

A world lay all beneath thee where to light;

And, strange thy taste,

Of all the varied scenes that met thine eye,

Of all the spots for building 'neath the sky,

To choose this waste.

Did fortune try thee? was thy little purse

Perchance run low, and thou, afraid of worse,

Felt here secure?

Ah, no! thou need'st not gold, thou happy one!

Thou know'st it not. Of all God's creatures, man

Alone is poor.

What was it, then? some mystic turn of thought

Caught under German eaves, and hither brought,

Marring thine eye

For the world's loveliness, till thou art grown

A sober thing that dost but mope and moan,

Not knowing why?

Nay, if thy mind be sound, I need not ask,

Since here I see thee working at thy task

With wing and beak.

A well-laid scheme doth that small head contain,

At which thou work'st, brave bird, with might and main,

Nor more need'st seek.

In truth, I rather take it thou hast got

By instinct wise much sense about thy lot,

And hast small care

Whether an Eden or a desert be

Thy home, so thou remainst alive, and free

To skim the air.

God speed thee, pretty bird; may thy small nest

With little ones all in good time be blest.

I love thee much;

For well thou managest that life of thine,

While I! Oh, ask not what I do with mine!

Would I were such!

The artist James Paterson (one of the "Glasgow Boys") stayed at Craigenputtock in 1882. The following is his account and sketches of his stay:

Fifty years have come and gone since this lonely moorland farmhouse was tenanted by Thomas Carlyle and his newly-wedded wife, Jane Welsh.

Very little changed is anything outward; quiet Craigenputtock was then, quiet it is still. You hear the wind moaning among the trees, the leaves falling to the ground, a distant murmur of water, the bleat of some sheep on the uplands. These are the sounds by night and by day; all else is silent. In how many places, dear to recollection, has time with its changes wrought sad havoc! Here it is not so. We can wander through the quiet fields and adjacent moor; the garden still yields its scanty stock of fruit and vegetables as of old; we may sit in the quondam drawing-room, look into the once snug study, and even invade the sanctuary of the kitchen, memorable as the scene of Mrs. Carlyle's culinary triumphs. A spirit seems ever to hang upon one's steps, a presence more real than the actual occupants. It is easy to imagine the then hale Carlyle, waling solitary out there on the darkest nights, wrestling with his soul for and answer to the questionings within him regarding the problems of life, while from the open window issues the sound of music; his wife is playing Scottish airs on the piano. These walls listened to the talk of the brilliant Jeffrey; here, too, the young Emerson first met his life-long friend, whom he overtarried not many days. Here Sartor Resartus was written, and the essays on Burns, on Scott, and others. It seems an intrusion a stranger being here, even now, uninvited. Very simply were the "curious impertinent" once baffled, but now the door stands open, and, though few indeed venture near, a visitors' book lies on the lobby table, where those who make a pilgrimage to the spot can register their names. Is it not in some sense sad the Craigenputtock was willed away to Edinburgh University? Without doubt a most deserving object; but would not the trustees have been equally satisfied, indeed more so, with an income of similar value in Consols? and we should have a representative of its former inmates still there in place of aliens. It was, however, done doubtless with no lack of thought.

Let us now look to Carlyle's own impressions of Craigenputtock, how he looked forward to his eight years' stay there, and how after all that rendered it dear had vanished, he turned to its memories in his old age with fond recollection. We make the following extracts, which speak for themselves, form the recently published life by Froude – "Craigenputtock, 10 June 1828. – We have arrived at Craigenputtock and found much done, but still much to do… Had we come hither out of whim one might have sickened and grown melancholy over such an outlook; but we came only in search of food and raiment, and will not start at straws. Away then with Unmuth und Verdruss! Man is born to trouble and toil as the sparks fly upwards… Of the Craig o' Putta I cannot yet rightly speak till we have seen what adjustment matters will assume. Hitherto, to say truth, all prospers as well as we could have hoped. The house stands heightened and white with rough cast, a light hewn porch in front, and cans on the chimney heads; and within it all seems firm and sound. During summer, as we calculate, it will dry and the smoke, we have reason to believe, is now pretty well subdued, so that on this side some satisfaction is to be looked for".

Two months later Carlyle again writes to his brother –

"Here is a drawing room with Goethe's picture in it, and a piano, and the finest papering on the walls; and I write even now behind it, in my own little library, out of which truly I can see nothing but a barn-roof, tree tops, and empty hay-carts, and under it perhaps a stagnant midden, cock with hens, overfed or else dazed with wet and starvation; but within which I may see a clear fire (of peats and Sanquhar coals), with my desk and books, and every accoutrement I need in fairest order. Shame befall me if I ought to complain, except it be of my own stupidity and pusillanimity".

In all this Carlyle seems to be struggling to look with a brave face on what was actually a temporary banishment from all the amenities of life, and his impatience now and again gets the better of him, breaking out into such expressions as "This Devil's Den," Craigenputtock. Poor Mrs. Carlyle's comment upon this period, in a letter written long afterwards, is laconic in its simplicity, and yet significant of her dreary life here. "I had gone with my husband to live in a little estate of peat bog." Indeed, her it suited much less than it did him. Unaccustomed to humble household duties, cut off from all society in which she had shone, and which she heartily enjoyed, for sole companion the preoccupied and moody, if loving, Carlyle, her lot was not one to be envied. But she had entered upon her married life in spite of the advice, and even the reproaches of her friends, and with a firm resolution to hope and wait for better days; and never while here, seldom indeed at any time, did she allow a word of complaint to fall from her lips. Nothing can adequately palliate the cruel thoughtlessness of Carlyle in taking a gently nurtured woman to rough it in this wild place. At no time very considerate of the feelings of others, it might have been expected that now, within six months of his marriage, he would have hesitated before taking this rash step. But it must be remembered that his experience of womankind from his infancy had been unusually limited, confined indeed almost exclusively to his mother and sisters, for whom he had the greatest regard. And when we think what are the ordinary and natural duties of a small farmer's wife and family, we are the less surprised at his failing to realise the difference in Mrs. Carlyle's position and upbringing. From his point of view, Craigenputtock seemed the only available course open to them. With his convictions on the sanctity of work and in their actual worldly circumstances, the move appeared absolutely necessary.

And now turning to Carlyle's reminiscences, in what light does his residence appear there after that period of his life, with its joys and sorrows, was long left behind?

"We were not unhappy at Craigenputtock; perhaps those were our happiest days. Useful continued labour, essentially successful, that makes even the moor green. I found I could do fully twice as much work in a given time there, as with my best efforts was possible in London, such the interruptions".

There is something pathetic in these few words, "Oh memory, when all things fade we fly to thee, our very sorrows time endeareth".

Let us look for a little somewhat more closely at this now celebrated place. Craigenputtock, meaning the wooded hill of the puttock, a kind of hawk, is a small estate on the borders of Dumfriesshire and Galloway, some 1,800 acres in extent, mostly moorland, and lying seven hundred feet above sea-level. Its precise situation is on the valley, running from the parish of Dunscore in Glencairn to the river Urr – flowing from the adjacent loch of the same name. It forms the boundary line of the two counties. Fully seventeen miles from Dumfries, the nearest railway station (save Auldgirth, which may be somewhat less), it will be seen to be sufficiently inaccessible. The nearest village, Corsock, is between three and four miles away. The house itself is not beautiful, not even what may be called picturesque. Where it stands nevertheless, it looks far from amiss, and seems not out of keeping with its barren surroundings. Still guarded by fine old trees and flanked by the orange and purple moors and Galloway hills, there is about it a quiet dignity which does not jar with its associations.

There appears no indication of the age of the present mansion, but from the style of its architecture, if an absolutely square building may be said to have any, it can no claims to antiquity, and probably dates from the beginning of this century. The windows were certainly fashioned since the abolition of the tax on window-glass. The front of the house, facing the north, commands no view whatever, and looks into a grassy bank, rising immediately towards a now spare plantation. To the back, where there might have been preserved a wide panorama of moorland and hills, all outlook is forbidden by the farm buildings, girdled again by trees. Indeed, so surrounded is the house, and so sheltered in its little hollow, that no sign of a habitation is visible from any distance, save from the moor above, where one may indeed see the roof and a window or more. On entering we find ourselves in a somewhat spacious lobby, hardly deserving the name of hall. To the right is the former drawing-room, and entering from it is the old study, a very tiny room which looks into the yard. On the left of the lobby is an apartment used by the Carlyles as the dining-room, and behind it is a bedroom. The kitchen, a large cheerful place, now the pleasantest room in the house, is built out at the back, as seen in the illustration. Ascending a narrow stone stair from the hall, we find ourselves on a small landing, whence four doors open into four several bedrooms, which complete the modest accommodation of Craigenputtock.

All prospect being denied us from the house itself, let us ascend Castrammon Hill, which rises in a gentle slope from the garden wall. A very easy climb of a quarter of an hour brings us to the summit, which may be a thousand feet above sea-level. Here, indeed, one has wide horizons. Looking towards the setting sun, we see almost at our feet the still waters of Loch Urr, and beyond range upon range of hills, leading to the distant Glenkens. To the right, a neighboring shoulder hinders our view, but again turning we have a range of country which extends over moorland, river, and plain, away down into Wordsworth's country. We can see where Ecclefechan must lie, whence the staid, serious boy started on his life's voyage. Mainhill and Scotsbrig are not far away, where the successive chapters of his history were unfolded. Again raising our eyes, beyond these filmy Cumberland hills, in a quiet street of quiet Chelsea we see in our "mind's eye" the scene of his later and last days, on the edge of that "Fog Babylon" he so railed against, and where the old Censor breathed his last – laying down his weary life, which to him had been one long struggle and tardy triumph; dying, to be brought home again, almost, within the shadow of the hill we are standing on, and laid by the dust of his father and mother in the quiet churchyard of Ecclefechan.

—James Paterson

See also

- List of country houses in the United Kingdom

- List of places in Dumfries and Galloway

- Writer's home