Copernican Revolution facts for kids

For simplicity, Mars' period of revolution is depicted as 2 years instead of 1.88, and orbits are depicted as perfectly circular or epitrochoid.

The Copernican Revolution was the paradigm shift from the Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which described the cosmos as having Earth stationary at the center of the universe, to the heliocentric model with the Sun at the center of the Solar System. This revolution consisted of two phases; the first being extremely mathematical in nature and the second phase starting in 1610 with the publication of a pamphlet by Galileo. Beginning with the publication of Nicolaus Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, contributions to the “revolution” continued until finally ending with Isaac Newton’s work over a century later.

Contents

Heliocentrism

Before Copernicus

The "Copernican Revolution" is named for Nicolaus Copernicus, whose Commentariolus, written before 1514, was the first explicit presentation of the heliocentric model in Renaissance scholarship. The idea of heliocentrism is much older; it can be traced to Aristarchus of Samos, a Hellenistic author writing in the 3rd century BC, who may in turn have been drawing on even older concepts in Pythagoreanism. Ancient heliocentrism was, however, eclipsed by the geocentric model presented by Ptolemy in the Almagest and accepted in Aristotelianism.

European scholars were well aware of the problems with Ptolemaic astronomy since the 13th century. The debate was precipitated by the reception by Averroes' criticism of Ptolemy, and it was again revived by the recovery of Ptolemy's text and its translation into Latin in the mid-15th century. Otto E. Neugebauer in 1957 argued that the debate in 15th-century Latin scholarship must also have been informed by the criticism of Ptolemy produced after Averroes, by the Ilkhanid-era (13th to 14th centuries) Persian school of astronomy associated with the Maragheh observatory (especially the works of Al-Urdi, Al-Tusi and Ibn al-Shatir).

The state of the question as received by Copernicus is summarized in the Theoricae novae planetarum by Georg von Peuerbach, compiled from lecture notes by Peuerbach's student Regiomontanus in 1454 but printed only in 1472. Peuerbach attempts to give a new, mathematically more elegant presentation of Ptolemy's system, but he does not arrive at heliocentrism. Regiomontanus himself was the teacher of Domenico Maria Novara da Ferrara, who was in turn the teacher of Copernicus.

There is a possibility that Regiomontanus already arrived at a theory of heliocentrism before his death in 1476, as he paid particular attention to the heliocentric theory of Aristarchus in a later work, and mentions the "motion of the Earth" in a letter.

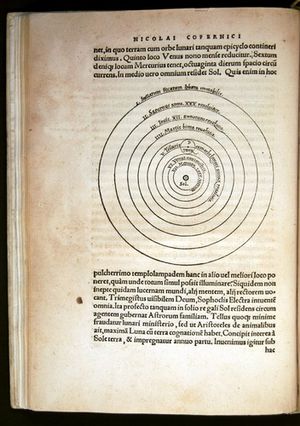

Nicolaus Copernicus

Copernicus studied at Bologna University during 1496–1501, where he became the assistant of Domenico Maria Novara da Ferrara. He is known to have studied the Epitome in Almagestum Ptolemei by Peuerbach and Regiomontanus (printed in Venice in 1496) and to have performed observations of lunar motions on 9 March 1497. Copernicus went on to develop an explicitly heliocentric model of planetary motion, at first written in his short work Commentariolus some time before 1514, circulated in a limited number of copies among his acquaintances. He continued to refine his system until publishing his larger work, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543), which contained detailed diagrams and tables.

The Copernican model makes the claim of describing the physical reality of the cosmos, something which the Ptolemaic model was no longer believed to be able to provide. Copernicus removed Earth from the center of the universe, set the heavenly bodies in rotation around the Sun, and introduced Earth's daily rotation on its axis. While Copernicus's work sparked the "Copernican Revolution", it did not mark its end. In fact, Copernicus's own system had multiple shortcomings that would have to be amended by later astronomers.

Copernicus did not only come up with a theory regarding the nature of the sun in relation to the earth, but thoroughly worked to debunk some of the minor details within the geocentric theory. In his article about heliocentrism as a model, author Owen Gingerich writes that in order to persuade people of the accuracy of his model, Copernicus created a mechanism in order to return the description of celestial motion to a “pure combination of circles.” Copernicus’s theories made a lot of people uncomfortable and somewhat upset. Even with the scrutiny that he faced regarding his conjecture that the universe was not centered around the Earth, he continued to gain support- other scientists and astrologists even posited that his system allowed a better understanding of astronomy concepts than did the geocentric theory.

Metaphorical usage

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason (1787 edition) drew a parallel between the "Copernican revolution" and the epistemology of his new transcendental philosophy. Kant's comparison is made in the Preface to the second edition of the Critique of Pure Reason (published in 1787; a heavy revision of the first edition of 1781). Kant argues that, just as Copernicus moved from the supposition of heavenly bodies revolving around a stationary spectator to a moving spectator, so metaphysics, "proceeding precisely on the lines of Copernicus' primary hypothesis", should move from assuming that "knowledge must conform to objects" to the supposition that "objects must conform to our [a priori] knowledge".

Much has been said on what Kant meant by referring to his philosophy as "proceeding precisely on the lines of Copernicus' primary hypothesis". There has been a long-standing discussion on the appropriateness of Kant's analogy because, as most commentators see it, Kant inverted Copernicus' primary move. According to Tom Rockmore, Kant himself never used the "Copernican revolution" phrase about himself, though it was "routinely" applied to his work by others.

After Kant

- Further information: Copernican principle

Following Kant, the phrase "Copernican Revolution" in the 20th century came to be used for any (supposed) paradigm shift, for example in reference to Freudian psychoanalysis or continental philosophy and analytic linguistic philosophy.

See also

In Spanish: Revolución de Copérnico para niños

In Spanish: Revolución de Copérnico para niños