Confederate Heartland Offensive facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Confederate Heartland OffensiveKentucky Campaign |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Western Theater of the American Civil War | |

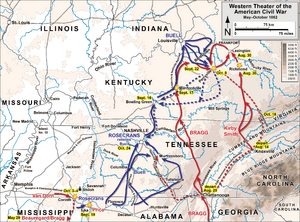

Map of Western Theater of the American Civil War, from Corinth, Mississippi, to Perryville, Kentucky

|

|

| Operational scope | Strategic offensive |

| Location | Tennessee and Kentucky 37°30′N 85°00′W / 37.5°N 85°W |

| Commanded by | |

| Date | August 14 – October 10, 1862 |

| Executed by | Army of Mississippi |

| Outcome | Union victory |

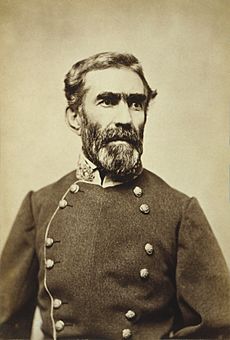

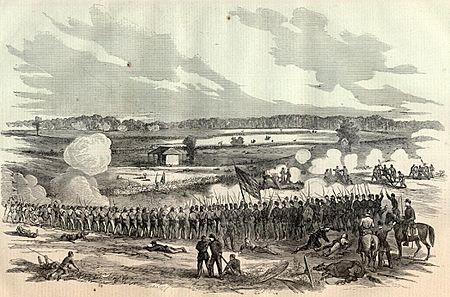

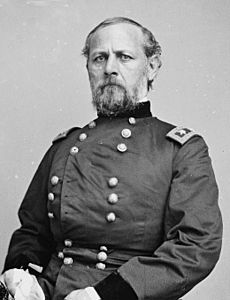

The Confederate Heartland Offensive (August 14 – October 10, 1862), also known as the Kentucky Campaign, was an American Civil War campaign conducted by the Confederate States Army in Tennessee and Kentucky where Generals Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith tried to draw neutral Kentucky into the Confederacy by outflanking Union troops under Major General Don Carlos Buell. Though they scored some successes, notably a tactical win at Perryville, they soon retreated, leaving Kentucky primarily under Union control for the rest of the war.

Contents

Background

Military situation

Western campaigns by Union forces earlier in 1862 had reaped much progress. The Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers had been opened to the U.S. Navy after successes at the battles of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson. The railroad hub at Corinth had been evacuated by the Confederates, causing most of West Tennessee to fall into Union control. New Orleans, the Confederacy's largest city at that time, had been captured by Admiral David Farragut. The city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, was now an important strategic aim for the Union commanders, as the western Confederates were "narrowed down all to the single line of [rail]road running east from Vicksburg." Consequentially, protecting the Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River became a top priority for the Confederacy. Confederate General Braxton Bragg decided to divert Union attention away from Vicksburg and from Chattanooga, Tennessee, which was being threatened by a large Union force under Don Carlos Buell, by invading the border Southern state of Kentucky. Kentucky, the most southern of the border southern states or the Upper South, produced cotton (in West Kentucky) and tobacco on large scale southern plantations in Central and Western Kentucky, and was the primary supplier of hemp for rope used in the cotton industry. The state was also a major slave trade center with Louisville being one of the biggest slave trading hubs in the South.

Kentucky, being a border Southern state in the Upper South, was among the chief places where the "Brother against brother" scenario was prevalent next to Tennessee, Virginia, and Missouri. Southern sympathizers in Kentucky had already seceded with delegates from 69 counties which was over half of Kentucky signed the ordinance of secession and joined the Confederacy, but had been unable to enforce their rule over more than half the state's territory representing the 69 counties whom had sent delegates to the Russellville Convention, as well as where Confederate battle lines had been drawn in 1861 and was the furthest extent of Confederate governance in Kentucky with Bowling Green being the capitol. Kentucky officially declared its neutrality at the beginning of the war, but after Confederate General Leonidas Polk unwisely decided to occupy Columbus in 1861, the legislature petitioned the Union Army for assistance. After early 1862 Confederate territorial control in Kentucky was reduced, and Kentucky came largely under Union control and occupation by 1863. But Kentucky also had a star on the Confederate flag, and seats with full representation in the Confederate Congress. In addition, many Confederate leaders, including John C. Breckinridge, were from Kentucky. (Jefferson Davis himself was a native Kentuckian born in Kentucky and grew up in Mississippi.) Abraham Lincoln was also born in Kentucky, living there until age 7. Most of Mary Todd Lincoln's relatives from the Lexington, Kentucky area were Confederate officers and prominent slave holders, and about 35,000 Kentuckians served as Confederate soldiers. But an estimated 125,000 Kentuckians served as Union soldiers counting freed slaves. Nearly 60 infantry regiments served in the Union armies, versus just 9 in the Confederate. However, a rather large number of cavalry outfits joined the latter under the CSA banner.

Campaign

In August, Confederate General Braxton Bragg invaded Kentucky, hoping that he could arouse supporters of the Confederate cause in the border state and draw Union forces under Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell back beyond the Ohio River. Bragg transported all of his infantry by railroads from Tupelo, Mississippi, to Chattanooga, Tennessee, while his cavalry and artillery moved by road. By moving his army to Chattanooga, he was able to challenge Buell's advance on the city.

Once his forces had assembled in Chattanooga, Bragg then planned to move north into Kentucky in cooperation with Lt. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, who was commanding a separate force operating out of Knoxville, Tennessee. He captured over 4,000 Union soldiers at Munfordville, and then moved his army to Bardstown. On October 4, he participated in the inauguration of Richard Hawes as the provisional Confederate governor of Kentucky. The wing of Bragg's army under Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk met Buell's army at Perryville on October 8 and won a tactical victory against him.

Kirby Smith pleaded with Bragg to follow up on his success: "For God's sake, General, let us fight Buell here." Bragg replied, "I will do it, sir," but then displaying what one observer called "a perplexity and vacillation which had now become simply appalling to Smith, to Hardee, and to Polk," he ordered his army to retreat through the Cumberland Gap to Knoxville. Bragg referred to his retreat as a withdrawal, the successful culmination of a giant raid. He had multiple reasons for withdrawing. Disheartening news had arrived from North Mississippi that Earl Van Dorn and Sterling Price had failed at Corinth, just as Robert E. Lee had failed in his Maryland Campaign. He saw that his army had not much to gain from a further, isolated victory, whereas a defeat might cost not only the bountiful food and supplies yet collected, but also his army. He wrote to his wife, "With the whole southwest thus in the enemy's possession, my crime would have been unpardonable had I kept my noble little army to be ice-bound in the northern clime, without tents or shoes, and obliged to forage daily for bread, etc."

Aftermath

The invasion of Kentucky was a strategic failure, although it had forced the Union forces out of Northern Alabama and most of Middle Tennessee; it would take the Union forces a year to regain the lost ground. A writer for the Cincinnati Commercial wrote "It was intended by Jeff Davis as a demonstration to keep the men of the West from being employed beyond the Alleghenies to aid McClellan, while the best of the Southern troops invaded Maryland and flanked Washington. Thousands of Union troops at Louisville, Cincinnati, Cumberland Gap and elsewhere ‘have been held at bay by no more than 40,000 rebels scattered throughout Kentucky."

Confederate General Joseph Wheeler claimed it was a success, stating ‘We recovered Cumberland Gap and redeemed Middle Tennessee and North Alabama. Two months of marches and battles by the armies of Bragg and Kirby-Smith had cost the Federals a loss in killed, wounded and prisoners of 26,530. We had captured 35 cannons, 16,000 stand of arms, millions of rounds of ammunition, 1,700 mules, 300 wagons loaded with military stores, and 2,000 horses.’ Confederate war clerk J.B. Jones recorded that Bragg "succeeded in getting away with the largest amount of provisions, clothing, etc., ever obtained by an army, including 8,000 beef cattle, 50,000 barrels of pork, and a million yards of Kentucky cloth."

Bragg was criticized by some newspapers and two of his own generals, Polk and William J. Hardee, but there was plenty of blame to spread among the Confederate high command for the failure of the invasion of Kentucky. The armies of Bragg and Kirby Smith suffered from a lack of unified command. Bragg can be faulted for moving his army away from Munfordville, out of Buell's path, a prime location for a battle to Confederate advantage. Polk can also be blamed for not following Bragg's instructions on the day before and the day of the battle. Confederate President Jefferson Davis kept Bragg in command of the Army of Tennessee. President Abraham Lincoln removed Buell from command of the Army of the Ohio for being too cautious in pursuit of Bragg, replacing him with Major General William Rosecrans. Buell would never get another command for the remainder of the war before mustering out of service in 1864.

Bragg himself blamed the failure in large part on the Kentuckians themselves, whom he had expected to flock to his banner in droves as he marched through the state. He had even brought along a wagon train of 20,000 additional rifles to arm the new recruits he expected to receive. In a letter to his wife, he said "Why should we be expected to conquer the whole Northwest with 35,000 men? Our only hope was in Kentucky. We were assured she would be with us to a man, yet in seven weeks occupation, with twenty thousand guns and ammunition burdening our train, we only succeeded in getting about two thousand men to join us and at least half of them have now deserted."

Although he succeeded in driving Bragg out of Kentucky, Buell's inability to achieve a decisive victory in battle or effectively pursue the Confederate army during its retreat effectively ended his military career. After the campaign was over, Buell was relieved of command, replaced by William Rosecrans, and investigated by a military commission. Though he was never found guilty of any misconduct, he would not receive another command before mustering out of service in May 1864.