Capture of Port Egmont facts for kids

Spanish engraving of the capture of Port Egmont in 1770

|

|

| Date | 10 June 1770 |

|---|---|

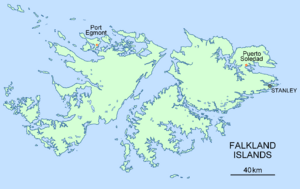

| Location | Port Egmont, Saunders Island, Falkland Islands |

| Participants | |

| Outcome | Spanish occupation Beginning of the Falklands Crisis. |

| Deaths | none |

The Capture of Port Egmont on 10 June 1770 was a Spanish expedition that seized the British fort of Port Egmont on the Falkland Islands, garrisoned since 1765. The incident nearly led to war between Great Britain and Spain, known as the Falklands Crisis.

The Spanish authorities in Buenos Aires, having been made aware of the British settlement, began issuing warnings to the British to leave Spanish territory. The British issued similar warnings to the Spanish to leave British territory.

British refusal to leave was met by Spanish force. Some 1,400 Spanish soldiers in five ships were dispatched from Buenos Aires to drive the British out of West Falkland. The British contingent could not resist such a force, so after firing their guns, they capitulated on terms, an inventory of their stores being taken, and were permitted to return to their own country in the Favourite.

Contents

Background

The Spanish were aware of the British presence on the Falklands before they took control of the French colony at Port Louis and renamed it Puerto Soledad in January 1767. On 28 November 1769, the officer in charge of the garrison on Saunders Island, Captain Anthony Hunt, observed a Spanish schooner hovering about the island surveying it. He sent the commander a message, by which he required of him to depart. An exchange of letters followed where each side asserted sovereignty and demanded the other depart. Hunt stated categorically that the Falkland Islands belonged to Britain and demanded that the Spanish leave.

Spanish capture

A squadron of frigates was dispatched by Francisco Bucareli, the governor of Buenos Aires, to expel the British. General Juan Ignacio de Madariaga’s frigates Industria, Santa Bárbara, Santa Catalina, and Santa Rosa, plus the Xebec Andaluz carrying 1,400 soldiers and a siege train under Colonel Don Antonio Gutiérrez, surprised the British settlement at Port Egmont. Although the British had erected a wooden blockhouse and an eight-gun battery of 12-pounders, they were no match for the Spanish force.

The Spaniards waded ashore and, after a token exchange of shots, Commander William Maltby and Commander George Farmer sued for terms. They and other settlers were detained for 20 days then permitted to sail for England aboard their sole remaining vessel, the 16-gun Favourite (the Swift had sunk at Port Desire three months before). The new occupiers renamed the town Cruzada and took over ownership. When news reached Britain it produced a public outcry.

Aftermath

News of this forcible eviction created much commotion in Britain. The British government was outraged at what it considered to be a despicable act, and the incident nearly led to an outbreak of war against Spain. The secretary of state, Lord Weymouth, addressed to the court of Madrid demanded: "the instant restoration of the colonists to Port Egmont, and for reparation of the insult offered to the dignity of the British crown, by their forcible removal from that place".

To these demands the Spanish court at first gave evasive answers, endeavouring to change the question at issue into one respecting the right of sovereignty over the islands. Lord Weymouth, however, refused positively to discuss that or any other matter, until the restoration and satisfaction which he demanded had been made; and the preparations for war which had been already commenced were prosecuted with vigor.

Whilst there was pressure for war on each side, rationality prevailed, when France, Spain's ally, refused to back Madrid in its predicament and the Spanish court was obliged to back down. It alleged the seizure had been done without Charles III’s authorisation and offered to restore Port Egmont as it existed before being captured. Prince de Maserano, the Spanish ambassador at London, declared, in the name of his sovereign, that "no particular orders" had been given to the governor of Buenos Aires on this occasion, though that officer had acted agreeably to his "general instructions and oath" as governor, and to the general laws of the Indies, in expelling foreigners from the Spanish dominions; and that he was ready to engage for the restoration of the British to Port Egmont, without however ceding any part of His Catholic Majesty's claim to the Falkland Islands; provided the king of England would in return disavow the conduct of Captain Hunt in ordering the Spaniards away from Soledad, which he asserted, had led to the measures taken by Bucareli.

The agreement finally took place on 15 September 1771, six months after the eviction, restoring the status quo as it existed before the capture of Port Egmont. By April the 32-gun frigate HMS Juno of Captain John Stott arrived to resume British rule, accompanied by the 14-gun Hound and the storeship Florida.

The short time frame is significant. Spain's military actions at Port Egmont aroused fears of war on the Continent, and in the context of Britain's overwhelming military superiority, the Spanish were more than willing to seek an early and amicable solution with their "injured" counterpart.

The British withdrew from the islands in pursuance of a system of retrenchment in 1774, leaving behind a flag and a plaque representing their claim to ownership. However, the British Charge d’Affaire later noted in a protest in 1829:

The withdrawal of His Majesty’s forces from these islands, in the year 1774, cannot be considered as invalidating His Majesty’s just rights. That measure took place in pursuance of a system of retrenchment, adopted at that time by His Britannic Majesty’s Government. But the marks and signals of possession and property were left upon the islands. When the Governor took his departure, the British flag remained flying, and all those formalities were observed which indicated the rights of ownership, as well as an intention to resume the occupation of that territory, at a more convenient season.

The Spanish reoccupied Port Egmont during the Anglo-Spanish War (1779-1783), but progressively lost control of its colonies. Spanish troops remained at Port Louis, known then as Port Soledad, until 1806 when Governor Juan Crisóstomo Martínez departed, leaving behind a plaque claiming sovereignty for Spain. The remaining Spanish settlers were removed in 1811 by order of the Spanish Governor in Montevideo.

See also

In Spanish: Combate de Puerto Egmont para niños

In Spanish: Combate de Puerto Egmont para niños