Calleva Atrebatum facts for kids

Site plan of Calleva Atrebatum

|

|

| Alternative name | Silchester Roman Town |

|---|---|

| Location | Silchester, Hampshire, England |

| Region | Britannia |

| Coordinates | 51°21′26″N 1°4′57″W / 51.35722°N 1.08250°W |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | Approximately 40 ha (99 acres) |

| History | |

| Builder | Atrebates tribe |

| Founded | Late 1st century BC |

| Abandoned | 5th to 7th century AD |

| Periods | Iron Age to Roman Empire |

| Site notes | |

| Management | English Heritage |

| Website | Silchester Roman City Walls and Amphitheatre |

| OS grid reference: SU639624 | |

Calleva Atrebatum ("Calleva of the Atrebates") was originally an Iron Age settlement, capital of the Atrebates tribe, and subsequently a town in the Roman province of Britannia. Its ruins lie to the west of, and partly beneath, the Church of St Mary the Virgin, Silchester, in the county of Hampshire. The church occupies a site just within the ancient walls of Calleva, although the village of Silchester itself now lies about a mile (1.6 km) to the west.

Contents

History

Unusually for a tribal capital in Britain, the Iron Age town was situated on the same site as the later Roman town, although the layout was revised.

Celtic Beginnings

The Celtic name "Calleva Atrebatum" can be translated to 'woody place'. The settlement was surrounded by dense woodlands that were used for fuel and to build structures. Because of its convenient location, it was a center of trading both within Britain and with civilizations across the Channel and as far away as the Mediterranean.

Iron Age

The Late Iron Age settlement at Silchester has been revealed by archaeology and coins of the British Q series to link Silchester with the seat of power of the Atrebates. Coins found stamped with "COMMIOS" show that Commius, king of the Atrebates, established his territory and mint here after moving from Gaul. The oppidum was situated on the edge of a gravel plateau, underlying the subsequent Roman town. The Inner Earthwork, constructed c. 1 AD, enclosed an area of 32 hectares, and a more extensive series of defensive earthworks was built in the wider area.

Small areas of Late Iron Age occupation have been uncovered on the south side of the Inner Earthwork and around the South Gate. More detailed evidence for Late Iron Age occupation was excavated below the Forum-Basilica. Several roundhouses, wells and pits occupy a north-east - south-west alignment, dated to c. 25 BC - 15 BC. Subsequent occupation, dated to c. 15 BC - AD 40/50, consisted of metalled streets, rubbish pits and palisaded enclosures. Imported Gallo-Belgic finewares, amphorae and iron and copper-alloy brooches show that the settlement was "high status". Also distinctive evidence for food was identified, including oyster shell, a large briquetage assemblage and sherds from amphorae which would have contained olive oil, fish sauce and wine.

Further areas of Late Iron Age occupation have been uncovered by the Insula IX 'Town Life' Project which has revealed a substantial boundary ditch c. 40 - 20 BC, a large rectangular hall c. 25 BC - AD 10 and the laying out of lanes and new property divisions c. AD 10 - 40/50. Archaeobotanical studies have demonstrated the import and consumption of celery, coriander and olive in Insula IX prior to the Claudian Conquest.

Roman

After the Roman conquest of Britain in 43 AD the settlement developed into the Roman town of Calleva Atrebatum.

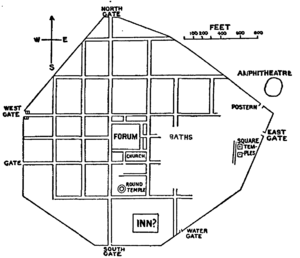

It was slightly larger, covering about 40 hectares (99 acres), and was laid out along a distinctive street grid pattern. The town contained a number of public buildings and flourished until the early Anglo-Saxon period.

A large mansio was situated in Insula VIII, near the South Gate, consisting of three wings arranged around a courtyard. A possible nymphaeum was located near to the amphitheatre to the north of the walled city.

Calleva was a major crossroads. The Devil's Highway connected it with the provincial capital Londinium (London). From Calleva, this road divided into routes to various other points west, including the road to Aquae Sulis (Bath); Ermin Way to Glevum (Gloucester); and the Port Way to Sorviodunum (Old Sarum near modern Salisbury).

The earthworks and, for much of the circumference, the ruined walls are still visible. The remains of the amphitheatre, added about AD 70-80 and situated outside the city walls, can also be clearly seen. The area inside the walls is now largely farmland with no visible distinguishing features, other than the enclosing earthworks and walls, with a tiny mediaeval church in one corner. At its peak, the Roman amphitheater would have housed around seven thousand spectators. Within, bear fighting, gladiator fighting, and other forms of entertainment were put on. Around the third century, renovations were made to the stadium including two new stadium entrances were added and the shape was turned into a more elliptical layout. After the Romans retreated, the British and the Anglo-Saxon continued to use the amphitheater.

In the southeast of the city were the "thermal baths". They belong to the earliest stone buildings of the city, which were perhaps built around 50 AD. The thermal baths are not aligned with the later city grid and the entrance area was rebuilt at a certain time to fit into the new road network. Several construction phases could be distinguished. At first they consisted of a portico, a palaestra and the bath rooms behind. The portico was later removed and the bathrooms divided in half, presumably so that men and women could bathe separately.

There is a spring that emanates from inside the walls, in the vicinity of the original baths, and which flows south-eastwards where it joins Silchester Brook. The Roman Calleva flourished (to nearly 10,000 inhabitants in the third/fourth century) around these springs that served the Roman baths recently excavated in summer 2019.

Sub-Roman & Medieval

After the Roman withdrawal from Britain, Calleva Atrebatum remained inhabited, but its fortunes began to decline. Major buildings at the site were used c. 400-430, but evidence of occupation begins to sharply decline after AD 450. According to Daniel G. Russo the hypothesis that the city remained in use during the sixth century, thanks to its sturdy walls, is "attractive," but based largely on guesswork, as "there is no firm written or archaeological evidence that organized Romano-British urban life existed at Calleva beyond c. 450 at the latest." This is in contrast to most other Roman towns in Britain, which continued to exist after the end of the Roman era; in fact, Calleva, is one of the six that did not survive the sub-Roman era, and disappeared in the Middle Ages. (That said, the historian David Nash Ford identifies the site with the Cair Celemion of Nennius's list of the 28 cities of Sub-Roman Britain, which, if true, would mean that the site was at least partially extant during the Early Middle Ages.) A hypothesis has emerged that the Saxons deliberately avoided Calleva after it was abandoned, preferring to maintain their existing centres at Winchester and Dorchester. There was a gap of perhaps a century before the twin Saxon towns of Basing and Reading were founded on rivers either side of Calleva. As a consequence, Calleva has been subject to relatively benign neglect for most of the last two millennia.

Culture

Agriculture

The study of waterlogged macrofossils through a series of wells throughout the abandoned civilization resulted in key evidence of animal stabling, hay meadows management, and the use of Heath resources (such as heathers, gorse, and heathland grasses). The most abundant crops that were found in the area are Capsella bursa pastoris, Chenopodium album, Polygonum aviculare, Stellaria media and Urtica urens, Fallopia convolvulus and Sisymbrium, The use of new oil crops and grassland management is evident that the agricultural upheaval changes were related to those that provide food to livestock rather than providing food to the population of the civilization. The development of the land represents a major change in the social organization and settlement form. This is evident in the ample earthwork or large artificial banks of soil. Located between the Hampshire chalk downs and Thames Valley, the civilization is on top of a gravel terrace of the River Kennet, a headwater of the Thames, covering it is a layer of tertiary clay and sand deposit. This creates a well-drained "brown-earth soil" which is traditionally seen as not ideal places for agricultural success. Palaeoenvironmental studies of the Early Iron Age at this site are evident in a largely cleared environment. Development of the Heath from this time is evidenced by pollen analysis.

Diet

The study of plant remains from the across the city and especially Insula IX have shown that spelt, wheat and barley were the most common cereals consumed. A wide range of fruits (apple, fig, grape), flavourings (celery, coriander, dill), and pulses (celtic bean, pea) were consumed. Many houses had their own rotary querns for grinding flour. Cattle, sheep/goat and pig were the major sources of meat.

Religion

There is a range of evidence for religious practices in the town. A possible church was located to the south-east of the Forum in Insula IV. The apsidally-ended basilica building has a layout comparable to early churches in the western Roman empire, but the date is likely to be pre-Constantinian. A Romano-Celtic temple was located in Insula XXXV, where an inscription shows a dedication by the guild of peregrini. Three Romano-Celtic temples were located within Insula XXX, just inside the east gate. These temples were constructed in the mid first century AD and went out of use after c. AD 200. A limestone head of Serapis was discovered in 1899 at Silchester Common.

Death and burial

Late Iron Age cremation burials have been excavated at Latchmere Green and Windabout Copse. The Roman cemeteries are thought to have been located to the north and west of the Outer Earthwork, and have not been investigated. A tombstone recovered in 1577 reads "To the memory of Flavia Victorina Titus Tammonius, Her husband set this up".

Defence

Built in two phases, the defense system of Calleva Atrebatum is evident in the remains of the North Gate. Construction of the wall surrounding the area first began around 200 AD. Parts of this rampart still remain in stone and tile remnants. In 270 AD, the defenses were strengthened with an even larger stone wall. Most likely defenses were increased due to the increasing amount of Saxon raids in the area. The defense systems worked to protect from local uprisings, pillaging, and invaders from abroad. They also allowed for traffic to be monitored both in and out of the city.

Economy

Craft production

Various craft activities have been evidenced through excavations in Insula IX, including bone- and antler- working, the working of copper-alloys, and leather-working. Imported whetstones were recycled into whetstones.

Building material

Production taking place in the area around Silchester includes a complex of tile kilns at Little London, including two tiles stamped with the title of the Emperor Nero. Because of the abundance of woods in the area, most of the structures were built out of timber.

Trade

A wide-range of objects were imported to Silchester from the Roman Empire, including an ivory razor handle, a handle from a Fusshenkelkruge and a Harpocrates figure from a Campanian brazier. Imported ceramics include Central Gaulish samian produced in Lezoux, Dressel 2-4 and 14 amphora, Rhineland white ware mortaria, Moselkeramik black slipped ware and Cologne colour coated ware.

Archaeology

Calleva Atrebatum was first excavated by the Rev. James Joyce who, in 1866, discovered the bronze eagle known as 'The Silchester Eagle' now in the Museum of Reading. It may originally have formed part of a Jupiter statue in the forum.

In the late nineteenth century, although it had long been known that there was an abandoned Roman civilization, excavations only first began by the landowner, Duke of Wellington. Reverend James Joyces was the designated observer and recorder of all archaeological records. His overall goal as the head was to reveal the complete plan of the Roman town. For the rest of the twentieth century, very little information was gathered about the civilization that was until the 1961 re-excavation of the early Christian Church where the researchers found that eighty to ninety percent of the excavation was done. Within those limited excavations, the foundation and the plans of the masonry buildings were exposed. They were discovered by digging trenches through the area. The architecture and archeology of the timber buildings of the ancient Roman town were misunderstood at the time of the excavation, timber was the most notable material.

Molly Cotton carried out excavations on the defences from 1938-39. Since the 1970s Michael Fulford and the University of Reading have undertaken several excavations on the town walls (1974–80), amphitheatre (1979–85) and the forum basilica (1977, 1980–86), which has revealed remarkably good preservation of items from both the Iron Age and early Roman occupations.

From 1997 to 2014 Reading University has made sustained and concentrated excavations in Insula IX. Results of the Late Roman, Mid Roman and Late Iron Age phases have been published. In 2013, excavations began in Insula III, investigating a structure identified by the Victorian excavations as a bathhouse. From 2018, the University of Reading has re-explored the previously excavated ruins of the public bathhouse looking at what earlier excavators may have missed.

Access

Now primarily owned by Hampshire County Council and managed by English Heritage, the site of Calleva is open to the public during daylight hours, seven days a week and without charge. The full circumference of the walls is accessible, as is the amphitheatre. The interior is farmed and, with the exception of the church and a single track that bisects the interior, inaccessible.

The Museum of Reading in Reading Town Hall has a gallery devoted to Calleva, displaying many archaeological finds from the various excavations.