Brian Josephson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Brian Josephson

|

|

|---|---|

Josephson in 2004

|

|

| Born |

Brian David Josephson

4 January 1940 Cardiff, Wales

|

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge (MA, PhD) |

| Known for | Josephson effect |

| Spouse(s) |

Carol Anne Olivier

(m. 1976) |

| Children | 1 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | University of Cambridge |

| Thesis | Non-linear conduction in superconductors (1964) |

| Doctoral advisor | Brian Pippard |

Brian David Josephson (born 4 January 1940) is a Welsh physicist and was professor emeritus of physics at the University of Cambridge. Best known for his pioneering work on superconductivity and quantum tunnelling, he shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physics with Leo Esaki and Ivar Giaever for his discovery of the Josephson effect, made in 1962 when he was a 22 year-old PhD student at Cambridge.

Josephson has spent his academic career as a member of the Theory of Condensed Matter group at Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory. He has been a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge since 1962, and served as professor of physics from 1974 until 2007.

In the early 1970s, Josephson took up transcendental meditation and turned his attention to issues outside the boundaries of mainstream science. He set up the Mind–Matter Unification Project at Cavendish to explore the idea of intelligence in nature, the relationship between quantum mechanics and consciousness, and the synthesis of science and Eastern mysticism, broadly known as quantum mysticism. He has expressed support for topics such as parapsychology, water memory and cold fusion, which has made him a focus of criticism from fellow scientists.

Contents

Early life and career

Education

Josephson was born in Cardiff, Wales, on 4 January 1940 to Jewish parents, Mimi (née Weisbard, 1911–1998) and Abraham Josephson. He attended Cardiff High School, where he credits some of the school masters for having helped him, particularly the physics master, Emrys Jones, who introduced him to theoretical physics. In 1957, he went up to Cambridge, where he initially read mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge. After completing Maths Part II in two years, and finding it somewhat sterile, he decided to switch to physics.

Josephson was known at Cambridge as a brilliant but shy student. Physicist John Waldram recalled overhearing Nicholas Kurti, an examiner from Oxford, discuss Josephson's exam results with David Shoenberg, reader in physics at Cambridge, and asking: "Who is this chap Josephson? He seems to be going through the theory like a knife through butter." While still an undergraduate, he published a paper on the Mössbauer effect, pointing out a crucial issue other researchers had overlooked. According to one eminent physicist speaking to Physics World, Josephson wrote several papers important enough to assure him a place in the history of physics even without his discovery of the Josephson effect.

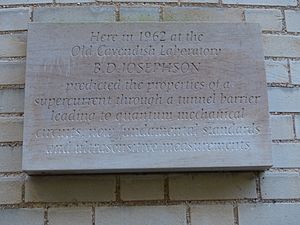

He graduated in 1960 and became a research student in the university's Mond Laboratory on the old Cavendish site, where he was supervised by Brian Pippard. American physicist Philip Anderson, also a future Nobel Prize laureate, spent a year in Cambridge in 1961–1962, and recalled that having Josephson in a class was "a disconcerting experience for a lecturer, I can assure you, because everything had to be right or he would come up and explain it to me after class." It was during this period, as a PhD student in 1962, that he carried out the research that led to his discovery of the Josephson effect; the Cavendish Laboratory unveiled a plaque on the Mond Building dedicated to the discovery in November 2012. He was elected a fellow of Trinity College in 1962, and obtained his PhD in 1964 for a thesis entitled Non-linear conduction in superconductors.

Discovery of the Josephson effect

Josephson was 22 years old when he did the work on quantum tunnelling that won him the Nobel Prize. He discovered that a supercurrent could tunnel through a thin barrier, predicting, according to physicist Andrew Whitaker, that "at a junction of two superconductors, a current will flow even if there is no drop in voltage; that when there is a voltage drop, the current should oscillate at a frequency related to the drop in voltage; and that there is a dependence on any magnetic field." This became known as the Josephson effect and the junction as a Josephson junction.

His calculations were published in Physics Letters (chosen by Pippard because it was a new journal) in a paper entitled "Possible new effects in superconductive tunnelling," received on 8 June 1962 and published on 1 July. They were confirmed experimentally by Philip Anderson and John Rowell of Bell Labs in Princeton; this appeared in their paper, "Probable Observation of the Josephson Superconducting Tunneling Effect," submitted to Physical Review Letters in January 1963.

Before Anderson and Rowell confirmed the calculations, the American physicist John Bardeen, who had shared the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics (and who shared it again in 1972), objected to Josephson's work. He submitted an article to Physical Review Letters on 25 July 1962, arguing that "there can be no such superfluid flow." The disagreement led to a confrontation in September that year at Queen Mary College, London, at the Eighth International Conference on Low Temperature Physics. When Bardeen (then one of the most eminent physicists in the world) began speaking, Josephson (still a student) stood up and interrupted him. The men exchanged views, reportedly in a civil and soft-spoken manner. See also: John Bardeen § Josephson effect controversy.

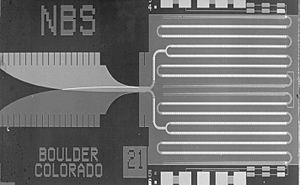

Whitaker writes that the discovery of the Josephson effect led to "much important physics," including the invention of SQUIDs (superconducting quantum interference devices), which are used in geology to make highly sensitive measurements, as well as in medicine and computing. IBM used Josephson's work in 1980 to build a prototype of a computer that would be up to 100 times faster than the IBM 3033 mainframe.

Nobel Prize

Josephson was awarded several important prizes for his discovery, including the 1969 Research Corporation Award for outstanding contributions to science, and the Hughes Medal and Holweck Prize in 1972. In 1973 he won the Nobel Prize in Physics, sharing the $122,000 award with two other scientists who had also worked on quantum tunnelling. Josephson was awarded half the prize "for his theoretical predictions of the properties of a supercurrent through a tunnel barrier, in particular those phenomena which are generally known as the Josephson effects". The other half of the award was shared equally by Japanese physicist Leo Esaki of the Thomas Watson Research Center in Yorktown, New York, and Norwegian-American physicist Ivar Giaever of General Electric in Schenectady, New York.

Positions held

Josephson spent a postdoctoral year in the United States (1965–1966) as research assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. After returning to Cambridge, he was made assistant director of research at the Cavendish Laboratory in 1967, where he remained a member of the Theory of Condensed Matter group, a theoretical physics group, for the rest of his career. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1970, and the same year was awarded a National Science Foundation fellowship by Cornell University, where he spent one year. In 1972 he became a reader in physics at Cambridge and in 1974 a full professor, a position he held until he retired in 2007.

A practitioner of Transcendental Meditation (TM) since the early seventies, Josephson became a visiting faculty member in 1975 of the Maharishi European Research University in the Netherlands, part of the TM movement. He also held visiting professorships at Wayne State University in 1983, the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore in 1984, and the University of Missouri-Rolla in 1987.

Parapsychology

Early interest and Transcendental Meditation

Josephson became interested in philosophy of mind in the late sixties and, in particular, in the mind–body problem, and is one of the few scientists to argue that parapsychological phenomena (telepathy, psychokinesis and other paranormal themes) may be real. In 1971, he began practising Transcendental Meditation (TM), which had been taken up by several celebrities, including the Beatles.

Winning the Nobel Prize in 1973 gave him the freedom to work in less orthodox areas, and he became increasingly involved – including during science conferences, to the irritation of fellow scientists – in talking about meditation, telepathy and higher states of consciousness. In 1974, he angered scientists during a colloquium of molecular and cellular biologists in Versailles by inviting them to read the Bhagavad Gita (5th – 2nd century BCE) and the work of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the founder of the TM movement, and by arguing about special states of consciousness achieved through meditation. "Nothing forces us," one scientist shouted at him, "to listen to your wild speculations." Biophysicist Henri Atlan wrote that the session ended in uproar.

In May that year, Josephson addressed a symposium held to welcome the Maharishi to Cambridge. The following month, at the first Canadian conference on psychokinesis, he was one of 21 scientists who tested claims by Matthew Manning, a Cambridgeshire teenager who said he had psychokinetic abilities; Josephson apparently told a reporter that he believed Manning's powers were a new kind of energy. He later withdrew or corrected the statement.

Josephson said that Trinity College's tradition of interest in the paranormal meant that he did not dismiss these ideas out of hand. Several presidents of the Society for Psychical Research had been fellows of Trinity, and the Perrott-Warrick Fund, set up in Trinity in 1937 to fund parapsychology research, is still administered by the college. He continued to explore the idea that there is intelligence in nature, particularly after reading Fritjof Capra's The Tao of Physics (1975), and in 1979 took up a more advanced form of TM, known as the TM-Sidhi program. According to Anderson, the TM movement produced a poster showing Josephson levitating several inches above the floor. Josephson argued that meditation could lead to mystical and scientific insights, and that, as a result of it, he had come to believe in a creator.

Fundamental Fysiks Group

Josephson became involved in the mid-1970s with a group of physicists associated with the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, who were investigating paranormal claims. They had organized themselves loosely into the Fundamental Fysiks Group, and had effectively become the Stanford Research Institute's (SRI) "house theorists," according to historian of science David Kaiser. Core members in the group were Elizabeth Rauscher, George Weissmann, John Clauser, Jack Sarfatti, Saul-Paul Sirag, Nick Herbert, Fred Alan Wolf, Fritjof Capra, Henry Stapp, Philippe Eberhard and Gary Zukav.

There was significant government interest at the time in quantum mechanics – the American government was financing research at SRI into telepathy – and physicists able to understand it found themselves in demand. The Fundamental Fysiks Group used ideas from quantum physics, particularly Bell's theorem and quantum entanglement, to explore issues such as action at a distance, clairvoyance, precognition, remote viewing and psychokinesis.

In 1976, Josephson travelled to California at the invitation of one of the Fundamental Fysiks Group members, Jack Sarfatti, who introduced him to others including laser physicists Russell Targ and Harold Puthoff, and quantum physicist Henry Stapp. The San Francisco Chronicle covered Josephson's visit.

Josephson co-organized a symposium on consciousness at Cambridge in 1978, publishing the proceedings as Consciousness and the Physical World (1980), with neuroscientist V. S. Ramachandran. A conference on "Science and Consciousness" followed a year later in Cordoba, Spain, attended by physicists and Jungian psychoanalysts, and addressed by Josephson, Fritjof Capra and David Bohm (1917–1992).

By 1996, he had set up the Mind–Matter Unification Project at the Cavendish Laboratory to explore intelligent processes in nature. In 2002, he told Physics World: "Future science will consider quantum mechanics as the phenomenology of particular kinds of organised complex system. Quantum entanglement would be one manifestation of such organisation, paranormal phenomena another."

Awards

- £1,000 New Scientist prize, 1969

- Research Corporation Award for outstanding contributions to science, 1969

- Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1970

- Fritz London Memorial Prize, 1970

- Guthrie Medal (Institute of Physics), 1972

- Van der Pol medal, International Union of Radio Science, 1972

- Elliott Cresson Medal (Franklin Institute), 1972

- Hughes Medal, 1972

- Holweck Prize (Institute of Physics and French Institute of Physics), 1972

- Nobel Prize in Physics, 1973

- Honorary doctorate, University of Wales, 1974

- Faraday Medal (Institution of Electrical Engineers), 1982

- Honorary doctorate, University of Exeter, 1983

- Sir George Thomson (Institute of Measurement and Control), 1984

Selected works

- (2012). "Biological Observer-Participation and Wheeler's 'Law without Law'," in Plamen L. Simeonov, Leslie S. Smith and Andrée C. Ehresmann (eds.), Integral Biomathics, Springer, pp. 244–252.

- (2005). "Foreword," in Michael A. Thalbourne and Lance Storm (eds.), Parapsychology in the Twenty-First Century, McFarland, pp. 1–2.

- (2003). "We Think That We Think Clearly, But That's Only Because We Don't Think Clearly," in Patrick Colm Hogan and Lalita Pandit (eds.), Rabindranath Tagore: Universality and Tradition, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, pp. 107–115.

- (2003). "String Theory, Universal Mind, and the Paranormal", arXiv, physics.gen-ph, 2 December 2003.

- (2002). "Beyond quantum theory: A realist psycho-biological interpretation of reality’ revisited", Biosystems, 64(1–3), January, pp. 43–45.

- (2000). "Positive bias to paranormal claims", Physics World, October.

- (1999). "What is truth?, Physics World, February.

- (1997). "Skeptics cornered", Physics World, September.

- (1997). "What is Music a Language For?" in Paavo Pylkkänen, Pauli Pylkkö, and Antti Hautamäki (eds.), Brain, Mind and Physics, IOS Press, pp. 262–265.

- (1996). "Consciously avoiding the X-factor", Physics World, December.

- with Jessica Utts (1996). "Do you believe in psychic phenomena? Are they likely to be able to explain consciousness?", Times Higher Education, 8 April.

- with Tethys Carpenter (1996). "What can Music tell us about the Nature of the Mind? A Platonic Model," in Stuart R. Hameroff, Alfred W. Kaszniak and Alwyn Scott (eds.), Toward a Science of Consciousness, MIT Press, pp. 691–694.

- with Colm Wall and Anthony Clark (1995). "Light Barrier", New Scientist, 29 April.

- (1994). "Awkward Eclipse", New Scientist, 17 December.

- (1994). BBC 'Heretic' series", Times Higher Education Supplement, 12 August.

- with Beverly A. Rubik (1992). "The challenge of consciousness research", Frontier Perspectives, 3(1), pp. 15–19.

- with Fotini Pallikari-Viras (1991). "Biological Utilization of Quantum Nonlocality", Foundations of Physics, 21(2), pp. 197–207 (also available here).

- (1990). "The History of the Discovery of Weakly Coupled Superconductors," in John Roche (ed.), Physicists Look Back: Studies in the History of Physics, CRC Press, p. 375.

- (1988). "Limits to the universality of quantum mechanics", Foundations of Physics, 18(12), December, pp. 1195–1204.

- with M. Conrad and D. Home (1987). "Beyond Quantum Theory: A Realist Psycho-Biological Interpretation of Physical Reality," in Alwyn van der Merwe, Franco Selleri and Gino Tarozzi (eds.), Microphysical Reality and Quantum Formalism, Springer, 1987, p. 285ff.

- with D.E. Broadbent (1981). "Perceptual Experiments and Language Theories", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 295(10772), October, pp. 375–385.

- with H. M. Hauser (1981). "Multistage Acquisition of Intelligent Behaviour" , Kybernetes, 10(1).

- with V. S. Ramachandran (eds.) (1980). Consciousness and the Physical World, Pergamon Press.

- with Richard D. Mattuck, Evan Harris Walker and Olivier Costa de Beauregard (1980). "Parapsychology: An Exchange", New York Review of Books, 27, 26 June, pp. 48–51.

- (1979). "Foreword," in Andrija Puharich (ed.), The Iceland Papers: Select Papers on Experimental and Theoretical Research on the Physics of Consciousness, Essentia Research Associates.

- (1978). "A Theoretical Analysis of Higher States of Consciousness and Meditation", Current Topics in Cybernetics and Systems, pp. 3–4.

- (1974). "The Artificial Intelligence/Psychology Approach to the Study of the Brain and Nervous System", Lecture Notes in Biomathematics, 4, pp. 370–375.

- (1974). "Magnetic field dependence of the surface reactance of superconducting tin at 174 MHz", Journal of Physics F: Metal Physics, 4(5), May, p. 751.

- (1973). "The Discovery of Tunnelling Supercurrents", Science, Nobel lecture, 12 December, pp. 157–164.

- (1969). "Equation of state near the critical point", Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics, 2(7), July.

- with J. Lekner (1969). "Mobility of an Impurity in a Fermi Liquid", Physical Review Letters. 23(3), pp. 111–113.

- (1967). "Inequality for the specific heat: II. Application to critical phenomena", Proceedings of the Physical Society, 92(2), October.

- (1967). "Inequality for the specific heat: I. Derivation", Proceedings of the Physical Society, 92(2), October.

- (1966). "Macroscopic Field Equations for Metals in Equilibrium", Physical Review, 152, December, pp. 211–217.

- (1966). "Relation between the superfluid density and order parameter for superfluid He near Tc", Physics Letters, 21(6), 1 July, pp. 608–609.

- (1965). "Supercurrents through Barriers", Advances in Physics, 14(56), pp. 419–451.

- (1964). Non-linear conduction in superconductors, (PhD thesis), University of Cambridge, December.

- (1964). "Coupled Superconductors", Review of Modern Physics, 36(1), pp. 216–220.

- (1962). "The Relativistic Shift in the Mössbauer Effect and Coupled Superconductors", submitted for Trinity College fellowship.

- (1962). "Possible new effects in superconductive tunnelling", Physics Letters, 1(7), 1 July, pp. 251–253.

- (1960). "Temperature-dependent shift of gamma rays emitted by a solid", Physical Review Letters, 4, 1 April.

See also

In Spanish: Brian David Josephson para niños

In Spanish: Brian David Josephson para niños

- Josephson voltage standard

- Josephson vortex

- Long Josephson junction

- Pi Josephson junction

- Phi Josephson junction

- List of Jewish Nobel laureates

- List of Nobel laureates in Physics

- List of physicists

- Scientific phenomena named after people