Black Canadians facts for kids

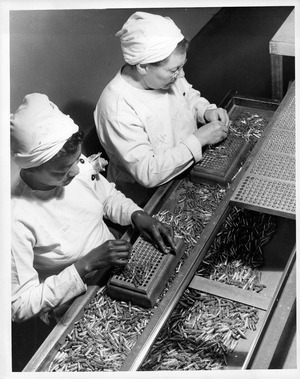

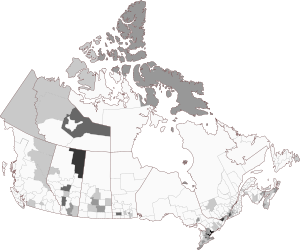

Black Canadians as percent of population by census division

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,547,870 (total, 2021) 4.26% of total Canadian population 749,155 Caribbean Canadians 2.2% of total Canadian population 2016 Census |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Toronto, Montreal, Brampton, Ajax, Edmonton, Calgary, Ottawa | |

| Ontario | 768,740 (5.5%) |

| Quebec | 422,405 (5.1%) |

| Alberta | 177,940 (4.3%) |

| British Columbia | 61,760 (1.3%) |

| Manitoba | 46,485 (3.6%) |

| Nova Scotia | 28,220 (3.0%) |

| Languages | |

| Canadian English • Canadian French • African Nova Scotian English • Caribbean English • Haitian Creole • African languages | |

| Religion | |

| 69.1% Christianity, 11.9% Islam, 18.2% Irreligiosity, 0.8% other faiths | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Afro-Caribbeans • African Americans | |

Black Canadians is a designation used for people of full or partial sub-Saharan African descent, who are citizens or permanent residents of Canada. The majority of "Black" Canadians are of Caribbean origin, though the population also consists of African-American immigrants and their descendants (including Black Nova Scotians), as well as many native African immigrants.

"Black" Canadians often draw a distinction between those of Afro-Caribbean ancestry and those of other African roots. The term African Canadian is occasionally used by some Black Canadians who trace their heritage to the enslaved peoples brought by British and French colonists to the North American mainland. Promised freedom by the British during the American Revolutionary War, thousands of Black Loyalists were resettled by the Crown in Canada afterward, such as Thomas Peters. In addition, an estimated 10 to 30 thousand fugitive slaves reached freedom in Canada from the Southern United States during the years before the Civil War with the Northern states, aided by people along the Underground Railroad.

Many Black people of Caribbean origin in Canada reject the term African Canadian as an elision of the uniquely Caribbean aspects of their heritage, and instead identify as Caribbean Canadian. Unlike in the United States, where African American has become a widely used term, in Canada, controversies associated with distinguishing African or Caribbean heritage have resulted in the term Black Canadian being widely accepted.

Black Canadians have contributed to many areas of Canadian culture. Many of the first visible minorities to hold high public offices have been Black, including Michaëlle Jean, Donald Oliver, Stanley G. Grizzle, Rosemary Brown, and Lincoln Alexander, in turn opening the door for other minorities. Black Canadians form the third-largest visible minority group in Canada, after South Asian and Chinese Canadians.

Contents

History

The Black presence in Canada is rooted mostly in voluntary immigration. Despite the various dynamics that may complicate the personal and cultural interrelationships between descendants of the Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia, descendants of former American slaves who viewed Canada as the promise of freedom at the end of the Underground Railroad, and more recent immigrants from the Caribbean or Africa, one common element that unites all of these groups is that they are in Canada because they or their ancestors actively chose of their own free will to settle there.

First Black people in Canada

- Further information: Slavery in Canada

The first recorded Black person to have potentially entered Canadian waters was an unnamed Black man on board the Jonas, which was bound for Port-Royal (Acadia). He died of scurvy either at Port Royal, or along the journey, in 1606. The first recorded Black person to set foot on land now known as Canada was a free man named Mathieu da Costa. Travelling with navigator Samuel de Champlain, de Costa arrived in Nova Scotia some time between 1603 and 1608 as a translator for the French explorer Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Monts. The first known Black person to live in what would become Canada was an enslaved man from Madagascar named Olivier Le Jeune, who may have been of partial Malay ancestry. He was first given to one of the Kirke brothers, likely David Kirke, before being sold as a young child to a French clerk and then later given to Guillaume Couillard, a friend of Champlain's. Le Jeune apparently was set free before his death in 1654, because his death certificate lists him as a domestique rather than a slave.

As a group, Black people arrived in Canada in several waves. The first of these came as free persons serving in the French Army and Navy, though some were enslaved or indentured servants. About 1,000 enslaved people were brought to New France in the 17th and 18th centuries. By the time of the British conquest of New France in 1759–1760, about 3,604 enslaved people were in New France, of whom 1,132 were Black and the rest First Nations people. The majority of the slaves lived in Montreal, the largest city in New France and the centre of the lucrative fur trade.

The majority of the enslaved Africans in New France performed domestic work and were brought to New France to demonstrate the prestige of their wealthy owners, who viewed owning a "slave" as a way of showing off their status and wealth. The majority of the enslaved Africans brought to New France were female domestic servants.

When New France was ceded to England in 1763, French colonists were assured that they could retain their human property. In 1790, when the British wanted to encourage immigration, they included in law the right to free importation of "Negroes, household furniture, utensils of husbandary or clothing." Although enslaved African people were no longer legally allowed to be bought or sold in Canada, the practice remained legal, although it was increasingly unpopular and written against in local newspapers. By 1829, when the American Secretary of State requested Paul Vallard be extradited to the United States for helping a slave to escape to Canada, the Executive Council of Lower Canada replied, "The state of slavery is not recognized by the Law of Canada. [...] Every Slave therefore who comes into the Province is immediately free whether he has been brought in by violence or has entered it of his own accord." The British formally outlawed slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833.

The descendants of Black slaves from New France and Lower Canada are white-passing French Canadians. Their family names are Carbonneau, Charest, Johnson, Lafleur, Lemire, Lepage, Marois, Paradis, etc.

African Americans during the American Revolution

At the time of the American Revolution, inhabitants of the British colonies in North America had to decide where their future lay. Those from the Thirteen Colonies loyal to the British Crown were called United Empire Loyalists and came north. Many White American Loyalists brought their enslaved African people with them, numbering approximately 2,500 individuals. During the war, the British had promised freedom and land to enslaved African people who left rebel masters and worked for them; this was announced in Virginia through Lord Dunmore's Proclamation. Enslaved African people also escaped to British lines in New York City and Charleston, and their forces evacuated thousands after the war. They transported 3,000 people to Nova Scotia.

This latter group was largely made up of merchants and labourers, and many set up home in Birchtown near Shelburne. Some settled in New Brunswick. Both groups suffered from discriminatory treatment by white settlers and prominent landowners who still held enslaved African people. Some of the refugees had been free black people prior to the war and fled with the other refugees to Nova Scotia, relying on British promises of equality. Under pressure of the new refugees, the city of Saint John amended its charter in 1785 specifically to exclude people of African descent from practising a trade, selling goods, fishing in the harbour, or becoming freemen; these provisions stood until 1870, although by then they were largely ignored.

In 1782, the first race riot in North America took place in Shelburne; white veterans attacked African American settlers who were getting work that the former soldiers thought they should have. Due to the failure of the British government to support the settlement, the harsh weather, and discrimination on the part of white colonists, 1,192 Black Loyalist men, women and children left Nova Scotia for West Africa on 15 January 1792. They settled in what is now Sierra Leone, where they became the original settlers of Freetown. They, along with other groups of free transplanted people such as the Black Poor from England, became what is now the Sierra Leone Creole people, also known as the Krio.

Although difficult to estimate due to the failure to differentiate enslaved African people and free Black populations, it is estimated that by 1784 there were around 40 enslaved Africans within Montreal, compared to around 304 enslaved Africans within the Province of Quebec. By 1799, vital records note 75 entries regarding Black Canadians, a number that doubled by 1809.

Maroons from the Caribbean

On 26 June 1796, Jamaican Maroons, numbering 543 men, women and children, were deported on board the three ships Dover, Mary and Anne from Jamaica, after being defeated in an uprising against the British colonial government. Their initial destination was Lower Canada, but on 21 and 23 July, the ships arrived in Nova Scotia. At this time Halifax was undergoing a major construction boom initiated by Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn's efforts to modernize the city's defences. The many building projects had created a labour shortage. Edward was impressed by the Maroons and immediately put them to work at the Citadel in Halifax, Government House, and other defence works throughout the city.

Funds had been provided by the Government of Jamaica to aid in the resettlement of the Maroons in Canada. Five thousand acres were purchased at Preston, Nova Scotia, at a cost of £3000. Small farm lots were provided to the Maroons and they attempted to farm the infertile land. Like the former tenants, they found the land at Preston to be unproductive; as a result they had little success. The Maroons also found farming in Nova Scotia difficult because the climate would not allow cultivation of familiar food crops, such as bananas, yams, pineapples, or cocoa. Small numbers of Maroons relocated from Preston to Boydville for better farming land. The British Lieutenant Governor Sir John Wentworth made an effort to change the Maroons' culture and beliefs by introducing them to Christianity. From the monies provided by the Jamaican Government, Wentworth procured an annual stipend of £240 for the support of a school and religious education.

After suffering through the harsh winter of 1796–1797, Wentworth reported the Maroons expressed a desire that "they wish to be sent to India or somewhere in the east, to be landed with arms in some country with a climate like that they left, where they may take possession with a strong hand". The British Government and Wentworth opened discussions with the Sierra Leone Company in 1799 to send the Maroons to Sierra Leone. In 1796, the Jamaican government initially planned to send the Maroons to Sierra Leone but the Sierra Leone Company rejected the idea. The initial reaction in 1799 was the same, but the company was eventually persuaded to accept the Maroon settlers. On 6 August 1800, the Maroons departed Halifax, arriving on 1 October at Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Upon their arrival in West Africa in 1800, they were used to quell an uprising among the black settlers from Nova Scotia and London. After eight years, they were unhappy with their treatment by the Sierra Reynolds Company.

Abolition of slavery

The Canadian climate made it uneconomic to keep enslaved African people year-round, unlike the plantation agriculture practised in the southern United States and Caribbean. Slavery within the colonial economy became increasingly rare. For example, the powerful Mohawk leader Joseph Brant purchased and enslaved an African American named Sophia Burthen Pooley, whom he kept for about 12 years before selling her for $100.

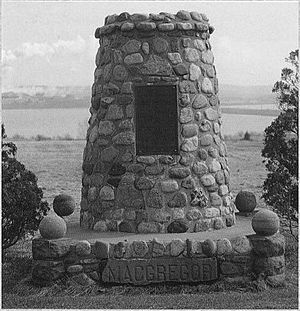

In 1772, prior to the American Revolution, Britain outlawed the slave trade in the British Isles followed by the Knight v. Wedderburn decision in Scotland in 1778. This decision, in turn, influenced the colony of Nova Scotia. In 1788, abolitionist James Drummond MacGregor from Pictou published the first anti-slavery literature in Canada and began purchasing slaves' freedom and chastising his colleagues in the Presbyterian church who owned slaves.

In 1790, John Burbidge freed the African people he had enslaved. Led by Richard John Uniacke, in 1787, 1789 and again on 11 January 1808, the Nova Scotian legislature refused to legalize slavery. Two chief justices, Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange (1790–1796) and Sampson Salter Blowers (1797–1832) were instrumental in freeing enslaved Africans from their enslavers (owners) in Nova Scotia. These justices were held in high regard in the colony.

In 1793, John Graves Simcoe, the first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, attempted to abolish slavery. That same year, the new Legislative Assembly became the first entity in the British Empire to restrict slavery, confirming existing ownership but allowing for anyone born to an enslaved woman or girl after that date to be freed at the age of 25. Slavery was all but abolished throughout the other British North American colonies by 1800. The Slave Trade Act outlawed the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807 and the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 outlawed slave-holding altogether in the colonies (except for India). This made Canada an attractive destination for many African descendant refugees fleeing slavery in the United States, such as minister Boston King.

War of 1812

The next major migration of Black people occurred between 1813 and 1815. Refugees from the War of 1812, primarily from the Chesapeake Bay and Georgia Sea Islands, fled the United States to settle in Hammonds Plains, Beechville, Lucasville, North Preston, East Preston, Africville and Elm Hill, New Brunswick. An April 1814 proclamation of Black freedom and settlement by British Vice-Admiral Alexander Cochrane led to an exodus of around 3,500 Black Americans by 1818. The settlement of the refugees was initially seen as a means of creating prosperous agricultural communities; however, poor economic conditions following the war coupled with the granting of infertile farmland to refugees caused economic hardship. Social integration proved difficult in the early years, as the prevalence of enslaved Africans in the Maritimes caused the newly freed Black Canadians to be viewed on the same level of the enslaved. Politically, the black Loyalist communities in both Nova Scotia and Upper Canada were characterized by what the historian James Walker called "a tradition of intense loyalty to Britain" for granting them freedom and Canadian Black people tended to be active in the militia, especially in Upper Canada during the War of 1812 as the possibility of an American victory would also mean the possibility of their re-enslavement. Militarily, a Black Loyalist named Richard Pierpoint, who was born about 1744 in Senegal and who had settled near present-day St. Catharines, Ontario, offered to organize a Corps of Men of Colour to support the British war effort. This was refused but a white officer raised a small black corps. This "Coloured Corps" fought at Queenston Heights and the siege of Fort George, defending what would become Canada from the invading American army. Many of the refugees from America would later serve with distinction during the war in matters both strictly military, along with the use of freed African people in assisting in the further liberation of African Americans enslaved people.

Underground Railroad

There is a sizable community of Black Canadians in Nova Scotia and Southern Ontario who trace their ancestry to African-American slaves who used the Underground Railroad to flee from the United States, seeking refuge and freedom in Canada. From the late 1820s, through the time that the United Kingdom itself forbade slavery in 1833, until the American Civil War began in 1861, the Underground Railroad brought tens of thousands of fugitive slaves to Canada.

The late Victorian era

Unlike in the United States, there were no "Jim Crow" laws in Canada at the federal level of government and outside of education, none at the provincial level of government.Instead segregation depended upon the prejudices of local school board trustees, businessmen, realtors, union leaders and landlords. The Common School Act of 1850 imposed segregation in Canada West while the Education Act of 1865 likewise imposed segregation in Nova Scotia, through in both cases school boards were given considerable leeway to decide to segregate or not. The school board for Halifax imposed racial segregation in 1865, but in 1883 the middle class black Haligonian community successfully petitioned the school board to allow their children to attend schools with white children following the closure of a school for black children in the north end of Halifax. However, the emergence of a black community in the Africville district in Halifax around 1848, made up of the descendants of American slaves who had escaped to Royal Navy warships operating in Chesapeake Bay in 1814, did lead to de facto segregation for most black Haligonian children.

Africville was described as a "close knit and self-sustaining community" which by the 1860s had its own school, general store, post office and the African United Baptist Church, which was attended by most residents. The black Canadian communities in the late 19th century had a very strong sense of community identity, and black community leaders in both Nova Scotia and Ontario often volunteered to serve as teachers. Through the budgets for black schools in Nova Scotia and Ontario were inferior to those for white schools, the efforts of black community leaders serving as teachers did provide for a "supportive and caring environment" that ensured that black children received at least some education. In a sign in pride in their African heritage, the principal meeting hall for black Haligonians was named Menelik Hall after the Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia who defeated the Italians in the First Italo-Ethiopian War (1895–1896), the only time an African nation had defeated a European nation during the "Scramble for Africa".

Immigration restrictions

In the early twentieth century, the Canadian government had an unofficial policy of restricting immigration by Black people. The huge influx of immigrants from Europe and the United States in the period before World War I included few black people, as most immigrants were coming from Eastern and Southern Europe.

1900s - 1930s

The flow between the United States and Canada continued in the twentieth century.

During the First World War, Black volunteers to the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) were at first refused, but in response to criticism, the Defence Minister, Sir Sam Hughes declared in October 1914 that recruiting colonels were free to accept or reject Black volunteers as they saw fit. Some recruiting colonels rejected all black volunteers while others accepted them; the ability of black men to serve in the CEF was entirely dependent upon how prejudiced and/or desperate for volunteers the local recruiting colonel was. Officially from 1916 onward black Canadians were only assigned to construction units to dig trenches on the Western Front. The Reverend William White, the chaplain of the all-Black Number 2 Construction Company of the CEF, founded on 5 July 1916, was named an honorary captain and thereby became one of the few Black men to receive an officer's commission in the CEF.

A wave of immigration occurred in the 1920s, with Black people from the Caribbean coming to work in the steel mills of Cape Breton, replacing those who had come from Alabama in 1899. Many of Canada's railway porters were recruited from the U.S., with many coming from the South, New York City, and Washington, D.C. They settled mainly in the major cities of Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg and Vancouver, which had major rail connections. The railroads were considered to have good positions, with steady work and a chance to travel.

As the Afro-Americans who came to work as railroad porters in Canada were all men, about 40 per cent of the Black men living in Montreal in the 1920s were married to white women.

1940s and 1950s

In the Second World War, Black volunteers to the armed forces were initially refused, but the Canadian Army starting in 1940 agreed to take Black volunteers, and by 1942 were willing to give Black officers commissions. Unlike in World War I, there were no segregated units in the Army and Black Canadians always served in integrated units. The Army was rather more open to Black Canadians rather than the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) and the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), which both refused for some time to accept Black volunteers. By 1942, the RCN had accepted Black Canadians as sailors while the RCAF had accepted Black service members as ground crews and even as airmen, which meant giving them an officer's commission as in the RCAF airmen were always officers. In 1942, newspapers gave national coverage when the five Carty brothers of Saint John, New Brunswick all enlisted in the RCAF on the same day with the general subtext being that Canada was more tolerant than the United States in allowing the Black Carty brothers to serve in the RCAF. The youngest of the Carty brothers, Gerald Carty, served as a tail gunner on a Halifax bomber, flying 35 missions to bomb Germany and was wounded in action.

The mobilization of the Canadian economy for "total war" gave increased economic opportunities for both Black men and even more so for Black women, many of whom for the first time in their lives found well-paying jobs in war industries.

In 1944, Ontario passed the Racial Discrimination Act, which banned the use of any symbol or sign by any businesses with the aim of racial discrimination, which was the first law in Canada intended to address the practice of many businesses of refusing to take Black customers.

In 1946, a Black woman from Halifax, Viola Desmond, watched a film in a segregated cinema in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, which led to her being dragged out of the theatre by the manager and a policeman. Desmond was convicted and fined for not paying the one cent difference in sales tax between buying a ticket in the white section, where she sat, and the Black section, where she was supposed to sit. The Desmond case attracted much publicity as various civil rights groups rallied in her defense. Desmond fought the fine in the appeals court, where she lost, but the incident led the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People to pressure the Nova Scotia government to pass the Fair Employment Act of 1955 and Fair Accommodations Act of 1959 to end segregation in Nova Scotia. Following more pressure from Black Canadian groups, in 1951 Ontario passed the Fair Employment Practices Act outlawing racial discrimination in employment and the Fair Accommodation Practices Act of 1955, which outlawed discrimination in housing and renting. In 1958, Ontario established the Anti-Discrimination Commission, which was renamed the Human Rights Commission in 1961. Led by the American-born Black sociologist Daniel G. Hill, the Ontario Anti-Discrimination Commission investigated 2,000 cases of racial discrimination in its first two years, and was described as having a beneficial effect on the ability of Black Canadians to obtain employment. In 1953, Manitoba passed the Fair Employment Act, which was modeled after the Ontario law, and New Brunswick, Saskatchewan and British Columbia passed similar laws in 1956, followed by Quebec in 1964.

The town of Dresden, Ontario was especially notorious for segregation with the majority of its Black residents living along two blocks on Main Street. To end segregation in Dresden, Hugh Burnett, a Black World War II veteran who owned a carpentry business in Dresden, founded the National Unity Association (NUA) in 1948. Most of leaders of the NUA were World War II veterans, who were incensed at the widespread discrimination in Dresden. After the all white council of Dresden dismissed Burnett's demand that a non-discrimination clause be added to all business licences, Burnett formed an alliance with Kalmen Kaplansky, the president of the Jewish Labour Committee. Burnett and Kaplansky waged an effective media campaign highlighting the injustice of veterans being treated like second class citizens, and in 1949 met with the Premier, Leslie Frost, to press their case. Frost proved to be sympathetic and in response to the lobbying of Burnett and Kaplansky, toughened the Racial Discrimination Act in 1951, passed the Fair Employment Practices Act the same year, followed by the Fair Accommodations Act of 1954. When McKay continued to turn away Black customers from Kay's Grill, he was convicted of racial discrimination. On 16 November 1956, two Black members of the NUA finally entered Kay's Grill and were served without incident.

1960s and 1970s

Starting in the 1960s with the weakening of ties to Britain together the changes caused by immigration from the West Indies, black Canadians have become active in the Liberal and New Democratic parties as well as the Conservatives. In 1963, the Liberal Leonard Braithwaite became the first black person elected to a provincial legislature when he was elected as a MPP in Ontario. In the 1968 election, Lincoln Alexander was elected as a Progressive Conservative for the riding of Hamilton West, becoming the first black person elected to the House of Commons. In 1979, Alexander become the first black federal Cabinet minister when he was appointed minister of labour in the government of Joe Clark. In 1972, Emery Barnes and Rosemary Brown were elected to the British Columbia legislation as New Democrats.

1980s and 1990s

In 1984, the New Democrat Howard McCurdy was elected to the House of Commons as the second black MP while Anne Cools became the first black Senator. In 1985, the Liberal Alvin Curling became the second black man elected to the Ontario legislature, and the first black person to serve as a member of the Ontario cabinet. In 1990, the New Democrat Zanana Akande became the first black female MPP in Ontario and the first black woman to join a provincial cabinet as the minister of community services in the government of Bob Rae. In 1990, the Conservative Donald Oliver became the first black man appointed to the Senate. In 1993, Liberal Wayne Adams became the first black person elected to the Nova Scotia legislation and the first black Nova Scotia cabinet minister. In the 1993 election, Jean Augustine was elected to the House of Commons as a Liberal, becoming the first female black MPs.

Images for kids

-

Mathieu da Costa, the first recorded free black person to arrive in the land that would become Canada centuries later

See also

In Spanish: Afrocanadiense para niños

In Spanish: Afrocanadiense para niños