Bank of United States facts for kids

The Bank of United States, founded by Joseph S. Marcus in 1913 at 77 Delancey Street in New York City, was a New York City bank that failed in 1931. The bank run on its Bronx branch is said to have started the collapse of banking during the Great Depression.

Formation

The Bank of United States was chartered on June 23, 1913 with a capital of $100,000 and a surplus of $50,000. The bank was founded by Joseph S. Marcus, a former president of the Public Bank, also of Delancey Street. Marcus, who was responsible for the building up of Public Bank, started the new bank, with the backing of several well-known financiers, because of a disagreement with other members of the management. Though the directors of Public Bank objected to the choice of name, arguing that "ignorant foreigners would believe that the United States government was interested in this bank and that it was a branch of the United States Treasury in Washington", the name was approved and the bank came into being. The use of such an appellation was outlawed in 1926 but did not apply retroactively.

The founder, Joseph S. Marcus, was a Jewish immigrant to the United States. Born in the town of Telz in Germany in 1862, he went to school in Essen and immigrated to the United States at the age of 17 and worked his way up from being a tailor, to a garment industry business, to a banker. He founded the Public Bank in 1906 and the Bank of United States in 1913. He died on July 3, 1927. He was also a philanthropist known for his donations to the Beth Israel Hospital and for the Hebrew Association for the Blind. His son, Bernard K. Marcus, a graduate of Worcester Academy and Columbia University, joined the bank as cashier in 1913 and became vice president in 1918.

Growth

The bank grew slowly, with only five branches by 1925. However, after the death of the founder, his son, Bernard Marcus who had been running the bank since 1919 grew the bank rapidly through a series of mergers until it had 62 branches by 1930. In April 1928, it merged with the Central Mercantile Bank and Trust Company with Bernard Marcus as the President. In August 1928, it absorbed the Cosmopolitan Bank.

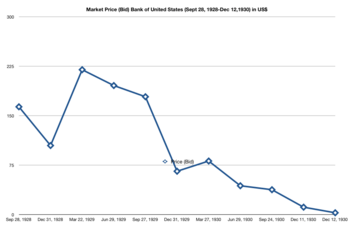

In April 1929, it absorbed the Colonial Bank and the Bank of the Rockaways. In May 1929, it merged with the Municipal Bank and Trust Company making the combined Bank of United States the third largest bank in New York City, and twenty-eighth in the United States. With a book value of $60 and a dividend payment of $2 for 1929, the president of the bank declared the bank to be on a sound footing in a letter to shareholders following the stock market failure on Black Tuesday.

In mid-1930, four leading New York banks-Manufacturers Trust Company, Public National Bank and Trust Company, International Bank and Trust Company, and the Bank of United States-began talks to merge and, on November 24, 1930, announced that they had agreed to form a mega-bank headed by J. Herbert Case, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

On December 8, 1930, unable to agree on merger terms, the plan was dropped, because, it later emerged, of difficulties in guaranteeing the deposits of Bank of United States, because of complications arising from the legal difficulties of the bank, and because of real estate mortgages and loans held by subsidiaries of the bank. Two days later, there was a run on a Bronx branch of the bank.

Failure

On December 10, 1930, a large crowd gathered at the Southern Boulevard branch in the Bronx seeking to withdraw their money, and started what is usually considered the bank run that started the Great Depression (though there had already been a wave of bank runs in the southeastern part of the U.S., at least as early as November 1930). The New York Times reported that the run was based on a false rumor spread by a small local merchant, a holder of stock in the bank, who claimed that the bank had refused to sell his stock.

By the midday, a crowd of 20,000 to 25,000 people had gathered and had to be controlled by the police, and by the end of the day 2,500 to 3,000 depositors had withdrawn $2,000,000 from the branch. However, most of the 7,000 depositors who came to withdraw their money left their assets in the bank. One person stood in line for two hours to claim his $2 account balance. As the news spread, there were smaller runs at several other branches in the Bronx as well as in the East New York section of Brooklyn.

The next day, fearing a run on the bank, the directors decided to close the bank and asked the Superintendent of Banks to take over the bank's assets. The stock market reacted negatively with the stock price of the bank, which had traded as high as $91.50 during the year (and a lifetime high of $231.25 in 1928) dropping from $11.50 to $3.00 (with a low of $2.00). Most other bank stocks also sold off. Joseph Broderick, the New York Superintendent of Banks, tried to arrange a merger with three other banks but the big Wall Street banks refused to help, possibly because of anti-semitism. Without the necessary $30 million bridge loan, the bank could not be saved.

The directors of the bank as well as of other New York banks were optimistic that the bank would reopen in a few weeks and members of the New York Clearing House Association offered to lend Bank of United States depositors 50% of their deposits. At the same time, the office of the New York State Bureau of Securities announced that they had been investigating charges that the Bank of United States had sold stock to depositors under a one-year guarantee against loss that they had not been honoring. The District Attorney's office undertook to examine the bank for possible crimes. Depositors thronged the bank branches but were turned away by mounted police. The Mayor of New York, Jimmy Walker, began legal action to recover $1.5 million which the city had in the bank. The New York Times reported that gross deposits in the bank had dropped from $212 million to $160 million between October 17, 1930 and December 11, 1930.

The closing of Bank of United States came as a shock to the banking industry, which had not seen a failure of a large New York bank since the stock market crash of 1929, and the first failure of such magnitude since the failure of the Knickerbocker Trust Company in 1907. Worried city and state officials tried to reassure the public by rushing through the program by which Bank of United States depositors could borrow money against their deposits. Some depositors started to receive their loans on December 23, 1930 and The New York Times reported that throngs of depositors lined up to receive their loans, many arriving hours before the branches opened and many were turned away because they could not be served by the end of the day.

Aftermath

Soon after the closing of the Bank of United States, another bank, the Chelsea Bank, was taken over by the state banking superintendent, Joseph A. Broderick, amidst allegations attributed to "reliable sources" that the Communist Party of America was actively trying to create a run on the bank (the Soviet Union was also accused of financing short sellers). Meanwhile, a $50 million stockholder suit was launched against the directors of the bank on the grounds of negligence and incompetence.

Among the 608 banks that closed in November and December 1930, the Bank of United States accounted for a third of the total $550 million deposits lost and, it is thought, that with its closure, bank failures reached a critical mass. People flocked to withdraw their money from other banks. In turn, the banks called in loans and sold assets in order to stay liquid. In that month alone, over 300 banks around the country failed.

After the bank's collapse in 1932, the bank building on Delancey Street was taken over by the Hebrew Publishing Company.