Baby bottle facts for kids

A baby bottle, nursing bottle, or feeding bottle is a bottle with an attached teat (also called a nipple in the US) on the top opening, on which can be suckled, and from thereby drank directly. It is typically used by infants and young children, or if someone cannot (without difficulty) drink from a cup, for feeding oneself or being fed. It can also be used to feed non-human mammals.

Hard plastic is the most common material used, being transparent, light-weight, and resistant to breakage. Glass bottles have been recommended as being easier to clean, less likely to retain formula residues, and relatively chemically inert. Hybrid bottles using plastic on the outside and glass inside have also been developed. Other materials used for baby bottles include food-grade stainless steel and silicone rubber.

Baby bottles can be used to feed human milk, infant formula, or pediatric electrolyte solution. A 2020 review reports that healthy term infants, when bottle‐feeding, "use similar tongue and jaw movements, can create suction and sequentially use teat compression to obtain milk, with minimal differences in oxygen saturation and SSB patterns" (suck–swallow–breath patterns). Sick or pre-term babies may not be able to take a bottle effectively and may need specialized care.

The design characteristics of the bottle and teat have been found to affect infant feeding and milk intake. Interactions between the infant and the caregiver feeding them affect the infant's milk intake during feeding. Whether the caregiver or the infant controls the feeding appears to affect the infant's ability to learn to self‐regulate their milk intake.

Proper cleaning and sterilization of bottles are recommended to avoid bacterial contamination and illness, particularly in areas where water quality and sanitary conditions are not good.

Contents

Design considerations

A typical baby bottle typically has four components: the first is the main container or body of the bottle. A teat, or nipple, is the flexible part of the bottle that the baby will suck from, and contains a hole through which the milk will flow. The collar goes over the nipple and typically screws onto the neck of the bottle, forming a seal. Most, but not all baby bottles will also have a cap or travel cover that goes over the teat to keep it clean and to prevent small spills. Some bottles may optionally have a disposable liner.

Design concerns for the making of baby bottles often reflect safety or comfort. A safe baby bottle should not break, should not come apart easily into small or potentially harmful components, should not be made of materials that pose a health risk, and should be easy to clean so as to avoid bacterial contamination and illness.

A bottle should also be comfortable for both caregiver and baby to use. Bottles that are lightweight and easy to hold can be desired by both babies and mothers. A variety of shapes are available. Designers may try to mimic the flow rate: the baby should be able to get enough nourishment, but at the same time not be overwhelmed or overfed.

Materials

Over time a wide variety of materials have been used for infant feeding vessels (see History). The materials now most commonly used in baby bottle containers are glass and some types of plastics. Food-grade stainless steel and silicone rubber are also used. Each of these four materials—plastic, glass, silicone and stainless steel—has advantages and disadvantages. The standard materials used in teats/nipples are latex rubber and silicone.

A number of countries have regulations about allowable food contact materials. Ideally, the material making up the bottle should react as little as possible with the material in the bottle. No material is completely inert, but glass and stainless steel are relatively neutral materials which tend to remain stable and not interact with foods. The disadvantages of glass are that it tends to be heavy and can break more easily.

Plastics are lightweight and resistant to breaking. Manufacturers find them easy to form into a variety of shapes. A wide variety of plastics have been developed, some of which are not well understood in terms of reactivity. Some plastics have been found to be reactive with fluids such as milk and infant formula. Chemicals such as Bisphenol A (BPA) may "leach" from a bottle into the substance it holds. In addition, plastics may be more likely to break down when heated or cooled, for example, when being heated in a microwave or being boiled to sterilize them.

Polycarbonate plastic was frequently used in baby bottles before 2011, and is still used in some countries. Polycarbonates contain Bisphenol A. Since 2008, at least 40 countries have banned the use of plastics containing Bisphenol A in baby bottles due to safety concerns (see Regulation). Bottles made of polycarbonate may be marked as "#7 PC".

Bisphenol S (BPS) and Bisphenol F (BPF) have been used as substitutes for BPA. They are structurally similar. Comparisons of BPA, BPS and BPF have found that these chemicals have similar potency and action to BPA and may pose similar dangers in terms of endocrine-disrupting effects. This has led to criticisms of the chemical industry and for calls to deal with bisphenols in groups, not individually. In 2021, the Canadian government agencies Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) and Health Canada (HC) held consultations with the goal of grouping 343 known BPA analogs and functional alternatives.

Polyethersulfone plastic (PES) does not contain BPA but does include Bisphenol S (BPS). An assessment of a variety of different baby bottles in use in 2016, reported 4 bottles to be of "high concern", 14 bottles to be of "concern"; and only 6 bottles to be of "no concern" These of "no concern" included two polyamide (PA) and two polyethersulfone (PES) bottles, a stainless steel bottle, and one of the 17 polypropylene (PP) bottles tested.

Phthalates, found in polyvinyl chloride (PVC), are another area of concern. Referred to as "everywhere chemicals" because they are so common, phthalates make plastic more flexible, and have been used in pacifiers and nipples or teats for bottles. Phthalates have been banned from use in feeding bottles in the EU. In the USA, there have been repeated calls for the removal of phthalates by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) and others. Their use in children's toys and products was somewhat restricted by the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act of 2008. Plastics labeled #3 may leach phthalates. Latex rubber nipples may contain phthalates, so silicone nipples may be recommended instead. Packaging may indicate whether a product is "BPA-free" or "phthalate-free".

Plastics may degrade over time in other ways, There are concerns that small beads of plastic may be released into fluids from some types of plastic bottles. In 2020 researchers reported that infant feeding bottles made out of polypropylene caused microplastics exposure to infants ranging from 14,600 to 4,550,000 particles per capita per day in 48 regions with contemporary preparation procedures. Microplastics release is higher with warmer liquids and similar with other polypropylene products such as lunchboxes. In 2022, the first study to examine the presence of plastic polymers in human blood found plastics of multiple types in the blood samples of 17 out of 22 healthy adults tested (nearly 80%). Medical experts have suggested reducing exposure to microplastics by not shaking plastic bottles or exposing them to high temperatures. Some recommend using alternative materials such as glass, silicone, or stainless steel.

Baby bottle nipples (also called teats) are typically made from either silicone or latex rubber. When used for nipples, silicone is clear, durable, and slightly harder than latex. Natural rubber latex teats are elastic, tear resistant, and may feel softer. Latex can absorb odors, while silicone does not. Latex can break down if exposed to sunlight. Some people have allergies to latex.

Size

Bottles tend to come in standard sizes, often 4 US fluid ounces (120 ml) and 8 US fluid ounces (240 ml). Smaller bottles may be lighter and easier to hold and are often used with younger, smaller infants. There are concerns that larger bottles may lead to over-feeding, since parents are likely to encourage a baby to "finish" a bottle during a feeding.

The height-to-width ratio of bottles is high (relative to adult cups) because it is needed to ensure the contents flood the teat when used at normal angles; otherwise the baby will drink air. However, if the bottle is too tall, it easily tips. There are asymmetric bottles that ensure the contents flood the teat if the bottle is held at a certain direction.

Shape

The shape of the bottle is related to both ease of use and ease of cleaning (see History). Designers sometimes suggest naturalistic designs. Other bottles have been invented with unique shapes designed to speed up the warming and cooling of milk, saving time, reducing bacterial growth, and reducing exposure to temperatures that can damage the nutrients in milk.

"Anti-colic" bottles have been put forward with the goal of reducing "gassiness" and distress when feeding. Designs often seek to minimize the sucking in of air by the baby while feeding. Some bottles try to minimize the mixing of air into the milk within the bottle. At the same time, it is desirable to avoid creating an internal vacuum as the infant sucks out fluids, since this will make it harder to feed. Designs may rely on the bottle's shape or incorporate different types of "venting".

Some vented bottles, as well as bottles which use a collapsible liner collapses as the formula is drained, have been assessed favorably. They were reported to be comparable in terms of milk intake, sucking patterns, and oxygenation.

A 2012 study comparing two types of vented bottles with anti-vacuum features found no differences in infant growth between randomized groups. "Bottle A", a partial anti-vacuum design, was rated by parents as easier to assemble and clean. Infants fed using "Bottle A" were reported to engage in less "fussing", but no difference were found in "crying" or "colic" or in rates of ear infection.

Health recommendations for the storage and handling of human milk typically focus on preventing the growth of dangerous bacteria, but some research is also being done on nutrition. Experimental studies have shown a degradation of retinol (Vitamin A) and α-Tocopherol (Vitamin E) content dependent upon the formation of bubbles in milk and in formula. Seven models of bottles were studied, from six companies. Less degradation occurred when using a bottle feeding system designed to minimize the mixing of air with the bottle's contents.

Teat flow rate

Teat characteristics can also have important implications for infant's sucking pattern and milk intake. Milk flow rate is defined as "the rate at which milk moves from the bottle nipple into the infant's mouth during bottle-feeding." Characteristics such as the shape of the nipple and the way it is perforated may impact flow rate and the coordination of sucking, swallowing and breathing during feeding.

Unfortunately, categorization and labeling of teats to indicate flow rate is neither standardized nor consistent. There is significant variability between and within brands and models. In one study, nipples labeled "Slow" or "Newborn" (0–3 months) had flow rates ranging from 1.68 mL/min to 15.12 mL/min."The name assigned to the nipple type does not provide clear information to parents attempting to choose a nipple". This may be of extra concern in the case of fragile infants. Specialized teats are available for infants with cleft palate.

Variations and accessories

Bottles may be designed as a complete "feeding system" that maximizes the reuse of the components. Such systems include a variety of drinking spouts for when the child is older. This converts the bottle into a sippy cup, a cup with lid and spout for toddlers, which is intermediate between a baby bottle and an open top cup. Bottles that are part of a feeding system may include handles that can be attached. The ring and teat may be replaced by a storage lid.

Accessories for bottles include cleaning brushes, or bottle brushes, sterilizers, and drying racks. Brushes may be specially designed for a specific manufacturer's bottles and teats. Bottle sterilizers use different techniques for sterilization, including ultraviolet light, boiling water, and hot steam.

Bottle warmers warm previously made and refrigerated formula. Coolers designed to fit a specific manufacturer's bottles are available to keep refrigerated formula cold. Special formula powder containers are available to store pre-measured amounts of formula so that caregivers can pre-fill bottles with sterile water and mix in the powder easily. The containers are typically designed to stack together so that multiple pre-measured amounts of formula powder may be transported as a unit.

Institutions can purchase ready-to-feed formula in containers that can be used as baby bottles. The lid screws off and is replaced by a disposable teat when the formula is ready to be used. This avoids storing the formula with the teat and possibly clogging the teat holes when formula is splashed within the bottle and dries.

Use

Cleaning and sterilization

Sterilization is a standard practice to prevent development of bacteria and resulting illness, that is more effective than sanitization. The Australian government and the United Kingdom's National Health Service guidelines recommend sterilization of baby bottles and other equipment either by using a cold water sterilizing solution such as by Milton sterilizing fluid, by steam sterilizing, or by boiling. It is important to clean and sterilize all parts of a bottle including containers, teats, and screw caps.

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suggests that it may be sufficient to clean bottles with soap and water, in a dishwasher or by hand. This recommendation is based on the assumption that water supplies are clean and sanitation standards are high. Some states, such as Illinois, continue to recommend sterilization in addition to washing. Alberta, Canada recommends sterilizing bottles until an infant is at least 4 months old.

However, there is evidence that bacteria such as E. coli can thrive in biofilms which form on the interior walls of the bottles. Gentle rinsing is not enough to prevent this. Even in developed areas, contamination continues to be a concern. In 2009 in the United Kingdom, researchers found contamination with Staphylococcus aureus in 4% of the baby bottles that parents reported were ready to fill after cleaning and disinfecting.

In lower-resource settings, risks of exposure to dangerous respiratory and enteric infections are higher. A study of children admitted to hospital in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, found that 52.1% of the bottles their caregivers considered clean were actually contaminated. This occurred even though caregivers reportedly followed many of the recommended cleaning practices for cleaning and sterilizing bottles. The most common mistake was to boil the bottles for less than the minimum time recommended by WHO.

Research into the preparation of infant formula in South Korea indicates significant levels of contamination can be transmitted through the handling of spoons and other utensils. Spoons, after being touched, were often left in the formula container, allowing bacteria to spread to the formula in the container. C. sakazakii, S. enterica, and S. aureus, all of which are potentially fatal, were able to surviving for weeks in contaminated infant formula.

Understanding how recommendations are interpreted is important: in one study, leaving a bottle in water that had been previously boiled in a kettle was believed to be "boiling" the bottle. Researchers emphasize that health providers need to better educate caregivers; and that practical methods of bottle hygiene need to be suited to use in field settings. For example, in Peru, easy-to-adopt practices like using a bottle brush and detergent gave greater advantages than difficult-to-achieve procedures like boiling a bottle. WHO notes that in cases where bottle feeding is to occur, much better education is needed on how to use bottles.

Age-appropriate use

Nipples (teats) are typically subdivided by flow rate, with the slowest flow rate recommended for premature infants and infants with feeding difficulties. However, flow rates are not standardised and vary considerably between brands.

The NHS recommends a sippy cup or beaker be introduced by 6 months and the use of bottles discontinued by 1 year. The AAP recommends that the cup be introduced by one year of age and that the use of the bottle by discontinued by 18 months. The use of bottles is discouraged beyond two years of age by most health organisations as prolonged use can cause tooth decay.

Regulation

While infant formula is highly regulated in many countries, baby bottles are not. Only the materials of the teat and bottle itself are specifically regulated in some countries (e.g. British Standards BS 7368:1990 "Specification for babies' elastomeric feeding bottle teats"). In the USA, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates teats and the bottle materials.

In 1985 the FDA restricted allowable levels of nitrosamines (many of which are carcinogens) released from bottle teats. Tests of bottle nipples available in the USA, Singapore, West Germany, England, Japan and Korea suggest that levels of nitrosamines in most rubber baby bottle teats are within recommended standards.

Another chemical that has been regulated is Bisphenol A (BPA), described as an endocrine disruptor in 1991. Ongoing research into the possible effects of BPA at levels of exposure far below the U.S. government's BPA safety standards has led to concerns about the safety of plastics, including baby bottles. A 1999 Consumer Reports study showed that some polycarbonate baby bottles released unsafe amounts of BPA. Concerns about BPA have been supported by further work. (Research into the effects of BPA has frequently been hotly contested and controversial and issues have been raised over research biases due to industry funding and conflicts of interest due to close ties between government consultants and BPA manufacturers.) One result has been proposals to change the testing paradigm for assessment of endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

Research and public pressure have led to bans on the use of Bisphenol A in bottles and cups to be used by children. In 2008 Walmart announced that it would stop selling baby bottles and food containers containing BPA. As of 2017, these were applied in at least 40 countries. Canada classified BPA as "toxic" in 2008 under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. In 2011 use of bisphenol A in baby bottles was forbidden in all EU countries, in China, in Malaysia, and South Africa. In July 2012, the FDA stated that BPA would no longer used in baby bottles and sippy cups, in response to a petition from the American Chemistry Council stating that this was now in line with industry practice. Other countries such as Argentina and Brazil followed suit by prohibiting bisphenol A in baby bottles. Korea has extended its BPA ban to include all children's utensils, containers and packaging as of January 2020. There are calls for increased regulation of BPA in India.

History

Throughout most of human history, infant nutrition has primarily depended on the availability of the child's mother or a wet nurse. Beliefs and behaviors relating to infant feeding also vary widely across countries, cultures and times. Mothers and caregivers have also sought additional ways to feed children, sometimes referred to as "hand feeding". As early as BC/BCE, Egyptian pottery shows images of women using animal horns to feed their babies.

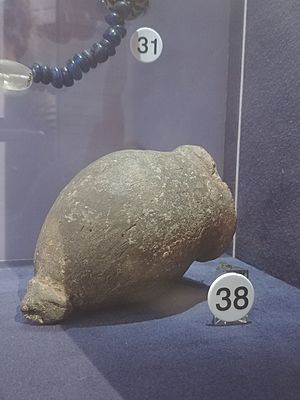

Containers with hard spouts date to early in recorded time, as evidence by archeological finds (see image). The first vessels known to be used for feeding infants had an opening at one end for filling the bottle, and a second at the other to be put into the baby's mouth. Examination of the organic residues on ancient ceramic baby bottles shows that they were used as early as BC/BCE to feed babies with animal milk.

Around BC/BCE to BC/BCE the Egyptians developed the ability to blow glass and the Romans blew clear feeding bottles of glass, but these did not retain obtain long-term popularity. Leather and wood were also used.

By the 1700s infant-feeding vessels such as the feeding-cups, bubby-pots, and sucking-pots were also being made from materials that included pewter, tin, and silver.

In the 19th century, changes to the feeding of infants were both socially and technologically driven. With industrialization, more mothers worked outside the home. Technological changes including the design of artificial feeding methods and the preparation of animal milks and other milk substitutes supported a transition to artificial feeding, but with mixed success. Understanding of both nutrition and sanitation lagged behind the introduction of artificial feeding methods, contributing to extremely high infant mortality rates in the Victorian era.

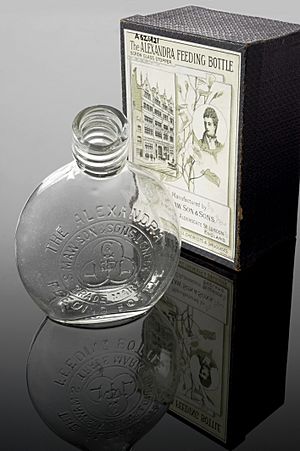

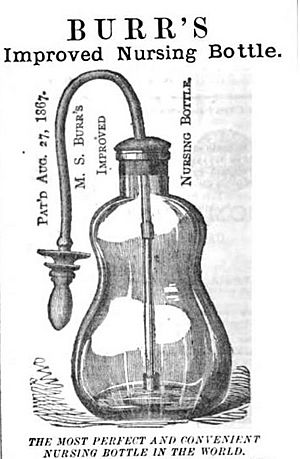

In the United States, the first glass nursing bottle was patented by C.M. Windship in 1841. In 1845 the Alexandra Feeder was marketed in England. In Paris, the "Biberon" was introduced by M. Darbo: it was reported to be quite popular in a review from 1851. As the group American Collectors of Infant Feeders notes, by "the late 1800s a large variety of glass nursing bottles were produced in the United States", and the U.S. Patent Office had issued more than 200 patents for various designs of nursing bottles by the 1940s—designed to lie flat or stand up straight, with openings on their sides or ends, with detachable or permanently attached nipples, etc.

The design of baby bottles and particularly the ease of cleaning them had potentially serious consequences for the health of the children using them. Estimates of infant mortality suggest that 20-30% of infants died in the first year of life during the late Victorian era. During the 1890s, at a time when England's childhood mortality rates (ages 1-5) were declining, infant mortality rates actually rose. A bottle with a long Indian rubber tube ending in a teat remained popular until the 1920s because even very young babies could feed independently. The feeding tubes could be bought separately and were sometimes used with empty whiskey or medicine bottles. Almost impossible to keep clean, this type has been nicknamed the "murder bottle".

Allen and Hanbury introduced a new bottle design with a removable valve and teat on the two ends in 1894, and an improved model, the Allenbury, in 1900. This "banana" bottle was easier to clean. Sometimes referred to as the "hygienic bottle", it helped to improve survival rates. Similar bottles were introduced by other manufacturers and remained popular from the 1900s to the 1950s. Eventually increased understanding of the causes and transmission of disease and improvements in medicine and public health began to reduce infant mortality.

Heat-resistant Pyrex bottles were introduced to the American and British markets at different times. Pyrex bottles were first introduced in the United States by Corning Inc. in 1922. They were offered in three shapes (narrow neck, wide mouth, and flat) and multiple sizes, for a total of ten varieties. By 1925, the product line had been limited to a small subset of the original shapes and sizes. In the 1950s a upright Pyrex bottle with a narrow neck was introduced. In the 1960s a wide-neck version was finally introduced to the UK market. The design of upright bottles with a wider mouth meant that they could be more easily cleaned, and sterilized in batches.

Soft nipples of various materials were introduced early in the history of feeding (e.g., leather, cork, sponge). Many were very difficult to clean and when unsanitary could pose a serious threat to infant health. Although Elijah Pratt of New York patented the first rubber nipple in 1845, it took until the 20th century before materials and technology improved sufficiently to allow manufacture of a soft nipple that was practical for use. The invention of rubber (1840s) provided a material that was soft. Early black Indian rubber "had a very strong pungent smell", and did not survive repeated exposures to hot water. However, by the early 1900s more pleasing rubber nipples could be manufactured in volume and could withstand the heat of sterilization.

During the 1940s nurse Adda M. Allen filed for multiple patents relating to the design of baby bottles, including the first disposable collapsible liner for a baby bottle. Her patent was one of many attempts to design a bottle to limit swallowing of air during feeding, and reduce gastric upset. A plastic bottle with a disposable liner was eventually tested at George Washington University Hospital and marketed by Playtex.

Innovations such as the introduction of a working check valve in the nipple (to provide unidirectional flow of the liquid food) appeared as early as 1948 in a patent to J.W. Less. This technology was picked up by others including Owens-Illinois Glass, eventually making its way into Gerber and all modern pressure-balancing bottle designs. It is also used for adult drinking cups and various other products requiring fluid flow under vacuum.

The modern business of producing bottles in the developed world is substantial. For 2018, the global baby bottle market was valued at 2.6 billion USD.

In 1999 it was reported that the UK "feeding and sterilising equipment sector ... stands at £49m… [where] [s]ales of feeding bottles account for 39%" or £19.1m of that market.

See also

In Spanish: Biberón para niños

In Spanish: Biberón para niños