Archie Mafeje facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Archie Mafeje

FAAS

|

|

|---|---|

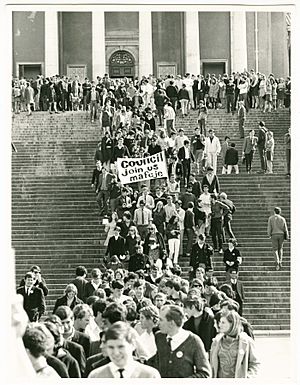

Archie Mafeje in Adderley Street, Cape Town in August 1961

|

|

| Born |

Archibald Boyce Monwabisi Mafeje

30 March 1936 Gubenxa village, Ngcobo (Thembuland), Cape Province, Union of South Africa

|

| Died | 28 March 2007 (aged 70) |

| Resting place | Ncambele village, Tsolo |

| Citizenship |

|

| Education | Nqabara Secondary School Healdtown Comprehensive School University of Cape Town (BA, MA) King's College, University of Cambridge (PhD) |

| Known for | Mafeje Affair Anti-apartheid movement Decolonisation of African anthropology |

| Spouse(s) | Shahida El Baz |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Social anthropology Political Anthropology Urban Sociology African history |

| Institutions | University of Dar Es Salaam Institute of Social Studies CODESRIA University of Namibia American University in Cairo |

| Thesis | Social and Economic Mobility in a Peasant Society: A Study of Commercial Farmers in Buganda (1968) |

| Doctoral advisor | Audrey Richards |

| Other academic advisors | Monica Wilson (MA) |

Archibald Boyce Monwabisi Mafeje (30 March 1936–28 March 2007), commonly known as Archie Mafeje, was a South African anthropologist and activist. Born in the Cape Province, Union of South Africa (now Eastern Cape), he received degrees from the University of Cape Town (UCT) and Cambridge University. He became a professor at universities in Europe, the Americas, and Africa, but spent most of his career away from apartheid South Africa after he was blocked from teaching at UCT.

Mafeje was an anti-apartheid activists in exile. As an important Pan-African intellectual, he studied African history and anthropology. He demanded that imperialist, Western ideals be eliminated from Black African anthropology, pushing for the decolonisation of African anthropology and challenging anthropology's entrenched notions of colonialism and racial hierarchy.

Contents

Life and career

Early life and education

Archibald Boyce Monwabisi Mafeje was born on 30 March 1936 in Gubenxa, a remote village in the Ngcobo (Thembuland), Cape Province, Union of South Africa. The Mafeje iziduko (or ‘clan name’) comes from the Mpondomise, an Xhosa sub-ethnic group.:25 His father, Bennett, was the headmaster of Gubenxa Junior School and his mother, Frances Lydia, was a teacher. His parent were married in Langa, Cape Town, in 1934, before moving to Gubenxa, and later to Ncambele village, Tsolo. Both were members of the Wesleyan Methodist Church.:25 Archie was the oldest of 7 siblings, the others being Vuyiswa (born in 1940), Mbulezi (born in 1942), Khumbuzo or Sikhumbuzo (born in 1944), Mzandile or Mlamli (born in 1947), Thozama (born in 1949), and Nandipha (born in 1954).

In 1951 and 1952, Mafeje completed his Junior Certificate at Nqabara Secondary School, a Methodist missionary school in Willowvale District. There, Nathaniel Honono, the school's headmaster and leader of the Cape African Teachers’ Association (CATA), introduced Mafeje and the other pupils to the politics of the Non-European Unity Movement (renamed Unity Movement of South Africa in 1964). The school was perceived as one of the best black secondary school in South Africa; however, following the Bantu Education Act of 1953, the apartheid government later took over the school in 1956.:27

Mafeje was then matriculated in 1954 to Healdtown Comprehensive School, Fort Beaufort, a Methodist missionary with a list of alums that includes Nelson Mandela and Robert Sobukwe. There, Mafeje was deeply influenced by Livingstone Mqotsi, a history teacher, and started participating actively in groups connected to the Non-European Unity Movement. Nykoa, asserted that at Healdtown, Archie became a radical atheist.:28 Mafeje joined the Fort Hare Native College, a black university in Eastern Cape, in mid-1955 to study zoology, but he left after one year.

Mafeje was then enrolled at the University of Cape Town (UCT) in 1957, joining the minority for non-white student numbering less than twenty out of five thousand students.:28 At UCT, he initially enrolled for a Bachelor of Science (BSc) in biology, but failed to pass the required courses.:28 Mafeje described how as a biology student in the late 1950s at UCT, he had been taught the same [racist attitudes] by my white professors who nonetheless regarded him as the other.":28 He then switched to studying social anthropology in 1959. In 1960, he completed a Bachelor of Arts in Urban Sociology with honours, followed by a Master of Arts (MA) with a distinction in Political Anthropology, before leaving the university in 1963. At UCT, he was part of the Society of Young Africa (SOYA) and the Cape Peninsula Student Union (CPSU). Francis Wilson (the son of his future mentor and supervisor, Monica Wilson), Fikile Bam and Mafeje held political debates with other students at ‘the Freedom Square’, below the Jameson Hall steps.:30 While they were compelled to read Lenin and Trotsky for their degree, Fikile Bam noted that Mafeje would frequently revert to Lenin in their theoretical and political disputes while being to quote the exact pages, down to the page numbers.:35 Nonetheless, Mafeje's friends recall that certain SOYA's members found his intellectualism and preference for theoretical argument irritating because they believed he spent too much time "hobnobbing with whites.":37

Mafeje's master's project was supervised by Monica Wilson, in which Mafeje's utilised his knowledge of the Xhosa language and his father's connections to complete the fieldwork in Langa between November 1960 and September 1962. Monica Wilson then wrote the work into a scientific paper titled Langa: A Study of Social Groups in an African Township, published as a book by Oxford University Press in 1963. However, in the early 1970s and as Mafeje's critique of [white] anthropology increased, Mafeje distanced himself from the book, and pointed to Wilson’s underlying Christian liberal ideology and liberal functionalism, which he perceived as a limitation because it favours Eurocentric theoretical approaches. Mafeje also completed fieldwork about the 1960s elections and political processes in the area for Gwendolen M. Carter.:50

On 16 August 1963, Mafeje spoke to a group that was gathered illegally, and as a result, he was detained. Then, he was sent to Flagstaff to stand trial. He was fined and sent back to Cape Town instead of being prosecuted. Mafeje then moved to the UK initially as a research assistant at the University of Cambridge after being recommended by Wilson, but then completed a Doctor of Philosophy under Audrey Richards at the King's College, University of Cambridge, in the late 1960s. During his PhD, he stayed in Uganda and carried out surveys on African farmers, while also working as Visiting Lecturer at Makerere University.:53 He submitted his doctoral thesis, which was titled Social and Economic Mobility in a Peasant Society: A Study of Commercial Farmers in Buganda.:33

Richards had doubts about Mafeje's work ethic' and ability to be an academic,' particularly when it came to handling theories, text analysis, and fieldwork.

The Mafeje Affair

Mafeje sought to return to University of Cape Town (UCT) and applied for a senior lecturer post that UCT widely advertised in August 1967. He was (unanimously) offered a post as Senior lecturer of social anthropology by the UCT Council. By law, the UCT could only admit white students unless suitable courses were not available at black universities. Still, the law did not explicitly bar UCT from hiring non-white faculty. Mafeje was scheduled to start in May 1968, but the UCT Council decided to withdraw Mafeje’s employment offer because the Government threatened to cut funding and impose sanctions on UCT should it appoint him.

The Council decision angered UCT’s students and led to protests followed by a sit-in, on 15 August 1968, to pressure the Council to reverse their decision. The sit-in gained international coverage and was considered part of the global protests of 1968 that received support from students mounting barricades in Paris and London. However, the protest crumbled when counter-protestors stormed the building with weapons and dogs while the photos of some of the protestors were passed around to create targets for the counter-protestors.' Students who participated in the sit-in later insisted that they had never met Mafeje and never sought to learn what had become of him. Ntsebeza asserted that, in the eyes of the students, the Mafeje affair was not about Mafeje, the individual, but rather about academic freedom and the autonomy of universities.

Shortly thereafter, Mafeje left South Africa to pursue a career abroad. During the negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa in the early 1990s, UCT offered Mafeje his 1968 senior lecturer position back on a one-year contract, but he declined the position as he was already a well-established professor. Mafeje said he found the offer "most demeaning."' In 1994, Mafeje applied for the A.C. Jordan Chair in African Studies at UCT, but his application was rejected as he was deemed "unsuitable for the position." Mahmood Mamdani, an Indian-born Ugandan professor, was appointed instead. He left after having disagreements with the administration on his draft syllabus of a foundation course on Africa called Problematizing Africa. This was dubbed the Mamdani Affair.

In 2002, Njabulo Ndebele, UCT Vice-Chancellor, re-opened the matter of the Mafeje affair. In 2003, UCT officially apologised to Mafeje and offered him an honorary doctorate, but he did not respond to UCT's offer. In 2008 - after Mafeje died - and on the incident's 40th anniversary, UCT formally apologised to Mafeje's family. Mafeje's family accepted the apology.

Academic career

Mafeje assumed the position of a senior lecturer in 1969, before becoming a Professor and the head of the Sociology Department at the University of Dar Es Salaam. However, he was seriously injured in a vehicle accident in 1971, after which he had to leave for Europe for reconstructive surgery and did not return following a spat with the Principal of the university and the Dean of the Faculty.:56 Between 1972 and 1975, Mafeje chaired the Institute of Social Studies' Urban Development and Labour Studies Program, where he first met Shahida El-Baz (Arabic: شهيدة الباز), an academic and activist from Egypt who became his wife later. Mafeje was appointed Queen Juliana Professor of Development Sociology and Anthropology by a Parliamentary act in 1973, aged 36. He became a Dutch citizen:58 and was appointed one of the Queen's lords with his name engraved on the prestigious blue pages of the Dutch National Directorate, as one of the first Africans to receive this honour.

With the assistance of Mafeje in 1973, the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) was founded.' Archie was appointed Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at American University in Cairo (AUC) in 1978 and later in 1994. He was known for not gaving his students a test as he preferred essays on which he made significant comments. According to his daughter Dana, Mafeje thought that ‘exams are for stupid people.’:72

Mafeje’s joined the Southern Africa Political Economy Series (SAPES) Trust in Harare, Zimbabwe in 1991 as a Visiting Fellowship.:72 However, the Mafeje left in the same year due to disagreement with the Trust's Executive Director, Ibbo Mandaza, who wanted Mafeje to keep the 09:00 to 17:00 office hours.:72 In 1992, Mafeje began a one-year Visiting Fellowship at Northwestern University in Evanston, United States.:72 From Northwestern University, Mafeje was chosen to lead the University of Namibia's Multidisciplinary Research Center in 1993. According to Shahida El-Baz, Mafeje's life was made a living hell by racist Namibians both within and outside of the university to the extent that he reuired a bodyguard.:72 The expereince severely impacted Mafeje. Mafeje departed Namibia and returned to AUC, Cairo in 1994.:72

Mafeje also served as a senior fellow and guest lecturer at several colleges and research centres in North America, Europe, and Africa. Throughout his career, Mafeje was a consultant to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).:60 Mafeje returned to South Africa in 2000, after spending more than 30 years in exile, to take the position of a Senior Research Fellow at the African Renaissance Centre at the National Research Foundation. He also joined CODESRIA's Scientific Committee in 2001.

Personal life and death

Mafeje married Nomfundo Noruwana (a nurse) in 1961, and the two of them had a son, Xolani, in 1962.:51 After getting into an accident.:51 After a few years, their were divorced.:51 Mafeje was married to Shahida in 1977; they had 4 children, Nandipha, Lumko Nkanyuza, Lungisa Nkanyuza, and Dana. Mafeje, however, had to convert to Islam before they were wed since Shahida was a Muslim.:59 In his later years, Mafeje would describe himself as ‘South African by birth, Dutch by citizenship, Egyptian by domicile, and African by love’.:58 Mafeje was a keen observer of Egyptian socio-political and economic changes; however, although he disliked Anwar Sadat for persecuting intellectuals, he was never personally involved in Egyptian politics.:65 Shahida remembers that Mafeje was reading in his study on 6 October 1981, when Sadata was assassination, Shahida then shouted while she was watching television news, "Archie, Sadat has been shot!".:65 The direct reply from Mafeje was, "Is he dead?" Shahida replied, "yes".:65 Mafeje popped up a bottle of champagne to toast.:65

Mafeje died in Pretoria on 28 March 2007, and was buried in Ncambele village in the Tsolo, next to his parents.:76

Personality

Mafeje was precieved by his peers as an independent thinker who is also extraordinarily "difficult", and by his students as someone who did ‘not suffer fools gladly’.:37

During one of his lectures, Thandika Mkandawire asked Mafeje to clarify or otherwise comment on condemning the unions that participated in the 1973 Durban strikes. Instead of responding to Mkandawire's question, Mafeje's siad "I am aware that you are from Malawi, you have no business asking me a question about South Africa while Malawi supports apartheid." Three days after the lecture, Mkandawire got a call from Mafeje, who strongly apologised and said there had been a major mistake. Mkandawire accepted the apologies and extended a dinner invitation to Mafeje at his residence in Stockholm.:69

Activism, research and ideology

Anti-apartheid and marxisim

Mafeje was part of SOYA and the African Peoples' Democratic Union of Southern Africa (APDUSA) which later became the Non-European Unity Movement. Both APDUSA and the Non-European Unity Movement promoted a non-collaboration with the oppressor stance and campaigned for complete democratic rights for all oppressed peoples on the basis of its Ten-Point Plan which positioned the land issue squarely at the heart of South Africa's liberation movement. According to Mafeje, APDUSA is better understood as Leninist than Trotskyist insofar as it emphasised the revolutionary potential of an alliance between workers and the "landless" peasants. This issue of “landless peasantry” remained essential to Mafeje's work,:31 although he later became critical to the Unity Movement.

Mafeje held Lenin and Mao in great esteem, rather than Trotsky who Mafeje accused of being ‘Eurocentrist’.:66 But according to Bongani, Trotsky 'Letter to South African Revolutionaries’ refute the notion.:33

Mafeje was an anti-apartheid activists in exile. In exile, Mafeje shared an animosity with white South African Communist Party (SACP) members including Joe Slovo, Dan O’Meara and Duncan Innes, with the later being integral to the Mafeje affair protest in 1968.:63 He accused them of practicing "white superiority" and "ideological superiority.":2

Decolonization of African identity

As an important Pan-African intellectual, Mafeje studied and wrote African history and anthropology. Mafeje published highly influential sociological essays and books in the fields of development and agrarian studies, economic models, politics, and the politics of social scientific knowledge production in Africa. He is considered one of the leading contemporary African anthropologists; however, he is more of a critical theorist than a field researcher.

Mafeje scholarly work significantly contributed to the decolonization of African identity and its historical past, criticising anthropology's typically Eurocentric techniques and beliefs. He demanded that imperialist and Western ideals be eliminated from Black African anthropology, which led to an examination of the discipline's founding principles and the methods by which academics approached the study of the attributed other. CODESRIA, which promoted an Afrocentrism and eliminated the Western perspective from pan-African research. He was one of the very first to dedicate himself to deconstructing the ideology of tribalism.

His work includes a whole series of debates and polemics with scholars like Harold Wolpe, Ali Mazrui, Achille Mbembe, and Sally Falk Moore, his favourite target who was an [white] anthropologist and Chair at Harvard University. Mafeje is part of the first generation of indigenous researchers, who reject the colonialist and neo-colonialist interpretations of Africa. According to Mafeje, [white] anthropology is inherently problematic since it is founded on the pursuit of otherness, which breeds racism and apartheid, as South Africa's experience plainly demonstrates. [White] Colonial anthropology is therefore doomed to the extent that it embodies the separation of the subject (the white anthropologist) and the object (the Africans). This is came to be know as the "epistemology of alterity in anthropology." However, Sally Falk Moore discredited Mafeje’s claims, and accused him for lunching unfounded personal attacks while “trying to kill a dead horse”, i.e., colonial anthropology.

Mafeje is perceived as one of Africa’s most prominent intellectuals who mixed his scholarship with his experience as an oppressed black person. After he passed away, his work gained wide attention and a growing interest from other African scholars, like Francis B. Nyamnjoh, Dani Wadada Nabudere, Helmi Sharawy, Lungisile Ntsebeza and Bongani Nyoka.

Awards and honours

Mafeje was elected a Fellow of the African Academy of Sciences in 1986. He received the Honorary Life Membership of CODESRIA in 2003 and was named CODESRIA Distinguished Fellow in 2005.

In 2008, University of Cape Town (UCT) posthumously awarded Mafeje an honorary doctorate in Social Science, established a scholarship in his honour and renamed the sit-in meeting room the Mafeje Room with a plaque honouring Mafeje, that now presides in front of the Senate meeting room that the protestors held throughout their action. UCT also established the Archie Mafeje Chair in Critical and Decolonial Humanities. In 2010, he was awarded posthumously an honorary doctorate of Literature and Philosophy by Walter Sisulu University.:76 In addition, Archibald Mafeje PhD Scholarship was established in 2014 by Tiso Foundation. The Africa Institute of South Africa (AISA) initiated the Archie Mafeje Annual Memorial Lecture series in 2016. The University of South Africa established the Archie Mafeje Institute for Applied Social Policy Research (AMRI) in 2017.