Abraham Isaac Kook facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Abraham Isaac Kookאברהם יצחק הכהן קוק |

|

|---|---|

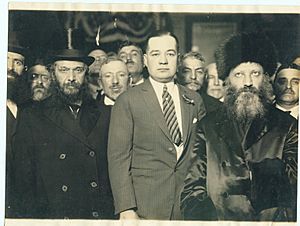

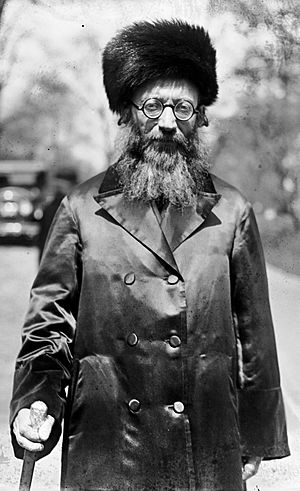

Abraham Isaac Kook in 1924

|

|

| Religion | Judaism |

| Denomination | Orthodox |

| Personal | |

| Born | 7 September 1865 Griva, Russian Empire (today Daugavpils, Latvia) |

| Died | 1 September 1935 (aged 69) Jerusalem, British Mandate of Palestine |

| Senior posting | |

| Title | First Chief Rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine |

| Buried | Mount of Olives Jewish Cemetery, Israel |

Abraham Isaac Kook (Hebrew: אַבְרָהָם יִצְחָק הַכֹּהֵן קוּק; 7 September 1865 – 1 September 1935), known as Rav Kook, and also known by the acronym HaRaAYaH (הראי״ה), was an Orthodox rabbi, and the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine. He is considered to be one of the fathers of religious Zionism and is known for founding the Mercaz HaRav Yeshiva.

Biography

Childhood

Kook was born in Griva (also spelled Geriva) in the Courland Governorate of the Russian Empire in 1865, today a part of Daugavpils, Latvia, the oldest of eight children. His father, Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Ha-Cohen Kook, was a student of the Volozhin yeshiva, the "mother of the Lithuanian yeshivas", whereas his maternal grandfather was a follower of the Kapust branch of the Hasidic movement, founded by the son of the third rebbe of Chabad, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn. His mother's name was Zlata Perl.

He entered the Volozhin Yeshiva in 1884 at the age of 18, where he became close to the rosh yeshiva, Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin (the Netziv). During his time in the yeshiva, he studied under Rabbi Eliyahu David Rabinowitz-Teomim (also known as the Aderet), the rabbi of Ponevezh (today's Panevėžys, Lithuania) and later Chief Ashkenazi Rabbi of Jerusalem. In 1886 Kook married Rabinowitz-Teomim's daughter, Batsheva.

Early career

In 1887, at the age of 23, Kook entered his first rabbinical position as rabbi of Zaumel, Lithuania. In 1888, his wife died, and his father-in-law convinced him to marry her cousin, Raize-Rivka, the daughter of the Aderet's twin brother. Kook's only son, Zvi Yehuda Kook, was born in 1891 to Kook and his second wife. In 1895, Kook became the rabbi of Bauska.

Between 1901 and 1904, he published three articles which anticipate the philosophy that he later more fully developed in the Land of Israel. Kook personally refrained from eating meat except on the Sabbath and Festivals; and a compilation of extracts from his writing, compiled by his disciple David Cohen, known as "Rav HaNazir" (or "the Nazir of Jerusalem") and titled by him "A Vision of Vegetarianism and Peace," depicts a progression, guided by Torah law, towards a vegetarian society.

Jaffa

In 1904, Kook was invited to become Rabbi in Jaffa, Ottoman Palestine, and he arrived there in 1905. During these years he wrote a number of works, mostly published posthumously, notably a lengthy commentary on the Aggadot of Tractates Berakhot and Shabbat, titled Eyn Ayah, and a brief book on morality and spirituality, titled Mussar Avicha.

It was in 1911 that Kook also maintained a correspondence with the Jews of Yemen, addressing some twenty-six questions to "the honorable shepherds of God's congregation" (Heb. כבוד רועי עדת ד) and sending his letter via the known Zionist emissary, Shemuel Yavneʼeli. Their reply was later printed in a book published by Yavneʼeli. Kook's influence on people in different walks of life was already noticeable, as he engaged in kiruv ("Jewish outreach"), thereby creating a greater role for Torah and Halakha in the life of the city and the nearby settlements. In 1913 Kook led a delegation of rabbis, including several leading rabbinic figures such as Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, to the many newly established secular "moshavot" (settlements) in Samaria and Galilee. Known as the "Journey of the Rabbis" the rabbis' goal was to strengthen Shabbat observance, Torah education, and other religious observances, with an emphasis on the giving of 'terumot and ma'asrot' (agricultural tithes) as these were farming settlements.

London and World War I

When the First World War began, Kook was in Germany, where he was interned as an alien. He escaped to London via Switzerland, but the ongoing conflict forced him to stay in the UK for the remainder of the war. In 1916, he became rabbi of the Spitalfields Great Synagogue (Machzike Hadath, "upholders of the law"), an immigrant Orthodox community located in Brick Lane, Spitalfields, London, and Kook lived at 9 Princelet Street, Spitalfields.

Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem

Upon returning from Europe in 1919, he was appointed the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem, and soon after, as first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Palestine in 1921.

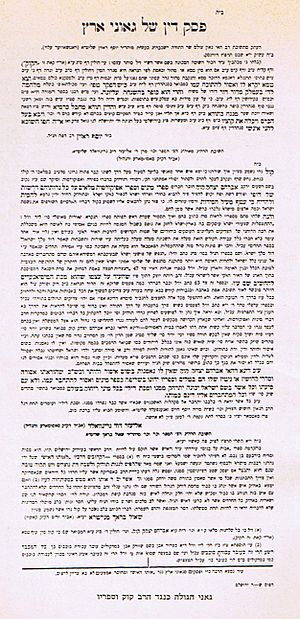

Although many of the new settlers were hostile to religion, Kook defended their behaviour in theological terms. His stance was deemed heretical by the traditional religious establishment and in 1921 his detractors bought up the whole edition of his newly published Orot to prevent its circulation, plastering the offending passages on the walls of Meah Shearim. Soon later, an anonymous pamphlet entitled Kol Ha-Shofar appeared containing a declaration signed by rabbis Sonnenfeld, Diskin and others saying: "We were astonished to see and hear gross things, foreign to the entire Torah, and we see that which we feared before his coming here, that he will introduce new forms of deviance that our rabbis and ancestors could not have imagined …. It is to be deemed a sorcerer's book? If so, let it be known that it is forbidden to study [let alone] rely on all his nonsense and dreams." It also quoted Aharon Rokeach of Belz who stated "And know that the rabbi from Jerusalem, Kook - may his name be blotted out - is completely wicked and has already ruined many of our youth, entrapping them with his guileful tongue and impure books." Returning to Poland after a visit to Palestine in 1921, Avraham Mordechai Alter of Ger wrote that he endeavoured to calm the situation by getting Kook to renounce any expressions which may have unwittingly resulted in a profanation of God's name. He then approached the elder rabbis of the Yishuv asking them to withdraw their denunciation. The rabbis claimed that their intention had been to reach a consensus on whether Kook's writings were acceptable, but their letter had been surreptitiously inserted by Kook's critics in to their inflammatory booklet without their knowledge. A harsh proclamation issued against Kook in 1926 contained letters from three European rabbis in which Yosef Rosin referred to him as an "ignorant bore", Shaul Brach intimated that his Hebrew initials spelt the word "vomit" and likened him to King Jeroboam known for seducing the masses to idolatry, and Eliezer David Greenwald declared him an untrustworthy authority on Jewish law adding that his books were full of heresy and should be burnt. When Jewish prayers at the Western Wall were broken up by the British in 1928, Kook called for a fast day, but as usual, the ultra-Orthodox community ignored his calls. As a 16-year-old student in 1932, Menachem Porush was expelled from Etz Chaim Yeshiva for shooting and burning an effigy of Kook. There were nevertheless other rabbis within Orthodoxy who spoke out in support of Kook, including the Chofetz Chaim and Isser Zalman Meltzer. It was claimed that Rabbi Solomon Eliezer Alfandari attributed the Chofetz Chaim's failed move to the land due to the disputes surrounding Rabbi Kook.

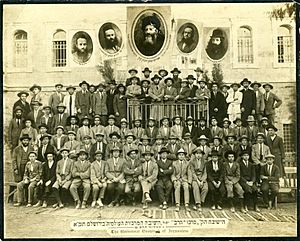

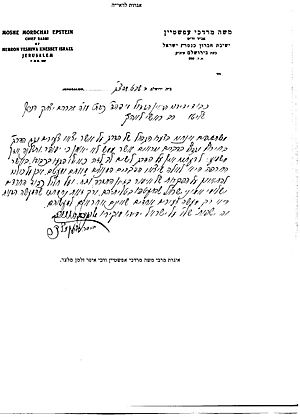

In March 1924, in an effort to raise funds for Torah institutions in Palestine and Europe, Kook travelled to America with Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Epstein of the Slabodka Yeshiva and the Rabbi of Kaunas, Avraham Dov Baer Kahana Shapiro. In the same year, Kook founded the Mercaz HaRav yeshiva in Jerusalem.

Kook died in Jerusalem in 1935 and his funeral was attended by an estimated 20,000 mourners.

Thought

Kook wrote prolifically on both Halakha and Jewish thought.

In line with many orthodox interpreters of the Jewish religion, Kook believed that there was a fundamental difference between Jews and Gentiles. The difference between a Jewish and a Gentile soul was greater than the difference between the soul of a Gentile and an animal.

Kook maintained communication and political alliances with various Jewish sectors, including the secular Jewish Zionist leadership, the Religious Zionists, and more traditional non-Zionist Orthodox Jews.

Inauguration of Hebrew University

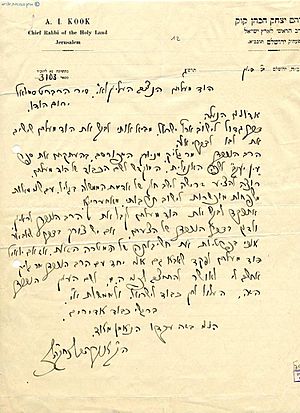

In 1928, Kook wrote a letter to Rabbi Joseph Messas (Chief Rabbi in Algeria), addressing certain misquotes which were erroneously being repeated in his name regarding a speech he gave at the inauguration of Hebrew University.

Theodor Herzl eulogy

His empathy towards the non-religious elements aroused the suspicions of many opponents, particularly that of the traditional rabbinical establishment that had functioned from the time of Turkey's control of greater Palestine, whose paramount leader was Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld. However, Sonnenfeld and Kook deeply revered each other, evidenced by their respectful way of addressing each other in correspondence.

Kook remarked that he was fully capable of rejecting, but since there were enough practicing rejection, he preferred to fill the role of one who embraces. However, Kook was critical of the secularists on certain occasions when they violated Halacha (Jewish law), for instance, by not observing the Sabbath or kosher laws, or ascending the Temple Mount.

Kook wrote rulings presenting his strong opposition to people ascending the Temple Mount, due to the Jewish Laws of impurity. He felt that Jews should wait until the coming of the Messiah when it will be encouraged to enter the Temple Mount. However, he was very careful to express the fact that the Kotel and the Temple Mount were holy sites that belong to the Jewish people.

Kook also opposed the secular spirit of the Hatikvah anthem and penned another anthem with a more religious theme entitled haEmunah.

Attitude toward Zionism

While Kook is considered one most important thinkers in modern Religious Zionism, his attitude towards the "Zionism" of his time was complex.

Kook enthusiastically supported the settlement of the land which Zionists of his time were carrying out. In addition, his philosophy "la[id] a theological foundation for marrying Torah study to Zionism, and for an ethos of traditional Judaism engaged with Zionism and with modernity". And unlike many of his religious peers, he showed respect towards secular Zionists, and willingly engaged in joint projects with them (for instance, his participation in the Chief Rabbinate).

At the same time, he was critical of the religious-Zionist Mizrachi movement of his time for "tamping down religious fervor and willingly accepting secondary status within the Zionist movement". In 1917 he issued a proclamation entitled Degel Yerushalayim, where he distinguished between "Zion" (representing political sovereignty) and "Jerusalem" (representing holiness), and arguing that Zion (i.e. Zionism) must take a cooperative but eventually subservient role in relation to Jerusalem. He then went on to found a "Degel Yerushalayim" movement separate from the Zionist movement, though this initiative had little success.

Legacy

The Israeli moshav Kfar Haroeh, a settlement founded in 1933, was named after Kook, "Haroah" being a Hebrew acronym for "HaRav Avraham HaCohen". His son Zvi Yehuda Kook, who was also his most prominent student, took over teaching duties at Mercaz HaRav after his death, and dedicated his life to disseminating his father's writings. Many students of Kook's writings and philosophy eventually formed Hardal Religious Zionist movement which is today led by rabbis who studied under Kook's son at Mercaz HaRav.

In 1937, Yehuda Leib Maimon established Mossad Harav Kook, a religious research foundation and notable publishing house, based in Jerusalem. It is named after Kook.

Support from rabbinic scholars

With the sudden public display of rare letters from the greatest Jewish scholars to Kook, many questions have emerged. Kook wrote that he was not part of any party – he simply viewed himself as a follower of God and the laws of the Torah. His relationship with many different types of leaders and laymen, was a part of his general worldview – that all Jews must work together in serving God and bringing the redemption. Also, one could see from the published letters, that the Haredi leadership was firm in its support of Kook, and in fact had an apparent fond relationship with him. The vast majority of the Haredi leaders publicized handwritten letters in support of Kook, when a few individuals were publicly disrespectful towards him. Kook embraced the support, but made clear that any insults were accepted by him without anger, for he viewed himself "as a servant of G-d," without interest in his personal honor.

Some examples of greetings in letters written by Jewish leaders to Kook:

Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski: "Our friend, the gaon, our master and teacher, Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Kook, shlita" and "The Glory of Honor, My Dear Friend, Ha-Rav Ha-Gaon, Ha-Gadol, the Famous One... The Prince of Torah, Our Teacher, Ha-Rav Avraham Yitzchak Ha-Cohen Kook Shlita..."

Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz: "The true gaon, the beauty, and glory of the generation, the tzaddik, his holiness, Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak, may his light shine, may he live for length of good days and years amen, the righteous Cohen, head of the beis din [court] in Jerusalem, the holy city, may it soon be built and established."

Rav Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn of Lubavitch: "The Gaon who is renowned with splendor among the Geonim of Ya'akov, Amud HaYemini, Patish HaChazak..."

Rav Chatzkel Abramsky: "The honored man, beloved of Hashem and his nation, the rabbi, the gaon, great and well-known, with breadth of knowledge, the glory of the generation, etc., etc., our master Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Hacohen Kook, shlita, Chief Rabbi of the Land of Israel and the head of the Beis Din in the holy city of Jerusalem"

Rav Yitzchak Hutner: "The glorious honor of our master, our teacher and rabbi, the great gaon, the crown and sanctity of Israel, Maran [our master] Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Hacohen Kook, shlita!"

Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer and Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein: "Our honored friend, the great gaon and glory of the generation, our master and teacher, Avraham Yitzchak Hacohen, shlita"

Criticism from rabbinic scholars

Others have maintained that Kook's views on Zionism stood outside the scope of traditional rabbinic teaching and that he was never accepted by the Haredi leadership.

Some examples of criticism from contemporaneous rabbinic leaders:

Rabbi Elchonon Bunim Wasserman: In response to a letter from Rabbi Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky of Eidah Hachareidit on whether they could partner with the Chief Rabbinate led by Kook: "I have heard that there was a suggestion that there should be a partnership between the Eidah Hachareidis and the Chief Rabinate . . .It is well known that the monies from that fund go to raise deliberate heretics, and therefore someone who encourages people to support such a fund is a machti es harabim (causes the public to sin) on the most frightful level . . .thus, besides the prohibition of befriending a wicked person, since we see that he praises resha'im (evil doers), there would also be an issue of an enormous chillum Hashem (desecration of G-ds name) throughout the world..."

Rabbi Yitzchak Zelig Morgenstern, the Rebbe of Sokolov: "Rav Kook, although he is a full and robust talmid chacham as well as an excellent orator, cannot be considered among the successors and perpetuators of the geonim (genius rabbinic scholars) and tzaddikim (righteous leaders) of the past generations. Rav kook is already connected with the spirit of the time, and speaks greatly about the techiyas umaseinu (our national rebirth). And despite the moral and religious decline of our generation, he sees in his mind's eye the techiyas hale'um (nationalistic rebirth) and the like, and he assigns to the Chief Rabbinate an important role in that process."

Resources

Writings

Orot ("Lights") books

- Orot – organized and published by Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, 1920. English translation by Bezalel Naor (Jason Aronson, 1993). ISBN: 1-56821-017-5

- Orot HaTeshuvah – English translation by Ben-Zion Metzger (Bloch Pub. Co., 1968). ASIN B0006DXU94

- Orot HaEmuna

- Orot HaKodesh - four volumes, organized and published by Rabbi David Cohen

- Orot HaTorah - organized and published by Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, 1940.

Jewish thought

- Chavosh Pe'er – on the mitzvah of tefillin. First printed in Warsaw, 1890.

- Eder HaYakar and Ikvei HaTzon - essays about the new generation and a philosophical understanding of God. First printed in Jaffa in 1906.

- Ein Ayah – commentary on Ein Yaakov the Aggadic sections of the Talmud. Printed in Jerusalem, 1995.

- Ma'amarei HaRe'iyah (two volumes) – a collection of articles and lectures, many originally published in various periodicals. Printed in Jerusalem, 1984.

- Midbar Shur – sermons written by Rav Kook while serving as a rabbi in Zaumel and Boisk in 1894–1896.

- Reish Millin – Kabbalistic discussion of the Hebrew alphabet and punctuation. Printed in London, 1917.

Halakha

- Be'er Eliyahu – on Hilchos Dayanim

- Orach Mishpat – Shu"t on Orach Chayim

- Ezrat Cohen – Shu"t on Even HaEzer

- Mishpat Kohen – Shu"t on issues relating to Eretz Yisrael

- Zivchei R'Iyah- Shu"t and Chidushim on Zvachim and Avodat Beit HaBchira

- Shabbat Haaretz hilchot shevi'it (shemittah)

Unedited and other

- Shmoneh Kvatzim – volume 2 of which was republished as Arpilei Tohar

- Olat Raiyah – Commentary on the Siddur

- Igrot HaRaiyah – Collected letters of Rav Kook

Biography

- Simcha Raz, Angel Among Men: Impressions from the Life of Rav Avraham Yitzchak Hakohen Kook Zt""L, translated (from Hebrew) Moshe D. Lichtman, Urim Publications 2003. ISBN: 965-7108-53-5 ISBN: 978-9657108536

- Dov Peretz Elkins, Shepherd of Jerusalem: A Biography of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, 2005. ISBN: 978-1420872613

- Yehudah Mirsky, "An Intellectual and Spiritual Biography of Rabbi Avraham Yitzhaq Ha-Cohen Kook from 1865 to 1904," Ph.D. Dissertation, Harvard University, 2007.

- Yehudah Mirsky, "Rav Kook: Mystic in a Time of Revolution (Jewish Lives)", Yale University Press, 2014, ISBN: 978-0300164244

Quotes

- Therefore, the pure righteous do not complain of the dark, but increase the light; they do not complain of evil, but increase justice; they do not complain of heresy, but increase faith; they do not complain of ignorance, but increase wisdom.

- There could be a freeman with the spirit of the slave, and there could be a slave with a spirit full of freedom; whoever is faithful to himself – he is a freeman, and whoever fills his life only with what is good and beautiful in the eyes of others – he is a slave.

Gallery

See also

In Spanish: Abraham Isaac Kook para niños

In Spanish: Abraham Isaac Kook para niños

- Hardal

- Religious Zionism

- Torat Eretz Yisrael